The Spectator: 20 February 2021: Why is the smoky, febrile art of Marcelle Hanselaar so little known? by Laura Gascoigne.

Her work is in the collections of the Ashmolean and Metropolitan Museum, New York, yet her powerful paintings and etchings remain under the radar.

I first became aware of the work of Marcelle Hanselaar in a mixed exhibition at the Millinery Works in Islington. All I remember now about the show, and my review, is that I said she could teach Paula Rego to suck eggs. From the mischievous energy packed into her small figurative paintings I assumed she was young enough to be Rego’s granddaughter. That was in 2003; she was pushing 60.

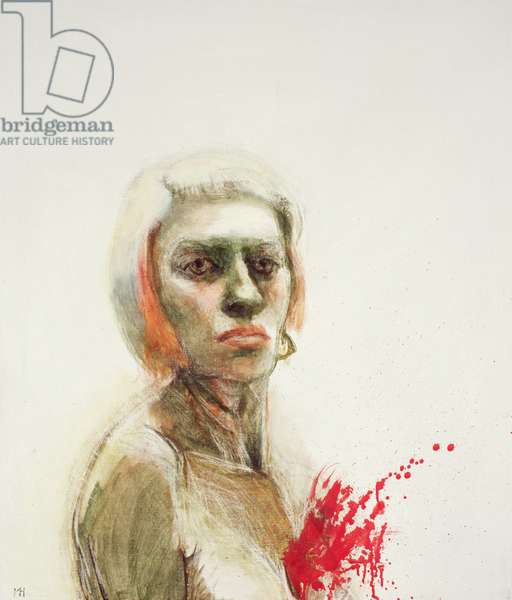

Born in Rotterdam in 1945, Hanselaar is essentially self-taught. She dropped out of art school in The Hague — it was the 1960s — and ran away to Amsterdam; what she learned about painting she picked up from the artists she lived with. In 1968 she drifted to India, where she lived in a cave as a sadhu, then — deciding that her ‘quest for truth had become muddled’ — she spent ten months in a Zen monastery in Japan. By the 1980s she had gravitated to London, painting lyrical abstracts and supporting herself by gardening. She was in her forties when, in 1992, the death of her disapproving mother — the woman she had always defined herself in opposition to — caused an identity crisis that triggered her first show of figurative paintings, Burying the Hatchet, remembering her mother, all horsey teeth and pearls, at her own age. ‘I had never in my life painted a face or hands.’ She did it from memory.

For Hanselaar, the urge to paint is born of contradiction: a mix of fascination and disgust. She is amused and touched by self-presentation and the way it misfires: step-in corsets that cause the surplus flesh to bulge, charmeuse slips that hang like sagging skin, lipstick that cracks and smears, ‘sexy and ungainly at the same time’. Costumes, a crucial part of her pictorial armoury, are not confined to vintage lingerie: the actors in her dramas are as likely to be decked in hand-me-downs from the old masters — a ‘Trophy Wife’ in a heavy chain necklace borrowed from Cranach, a ‘Child Soldier’ in a 17th-century Dutch jerkin.

Fire-breathing dogs in Swiss voile aprons freely interact with – and pleasure – their human counterparts

Her battery of props is equally eclectic, ranging from the domestic to the torturous, from the colander to the bed of nails. Add in the performing animals, the chimpanzees in party frocks and fire-breathing dogs in Swiss voile aprons freely interacting with — even pleasuring — their human counterparts, and the atmosphere becomes decidedly dangerous. It’s often smoky: a blackbird tries to escape from a burning cage, volcanoes throw up jets of fiery sparks, towering chimneys puff out billows of black smoke, all stoked by a febrile, uncensored imagination. ‘For a long time I worried that the subject should have authority and be acceptable. Now I’ll paint anything.’

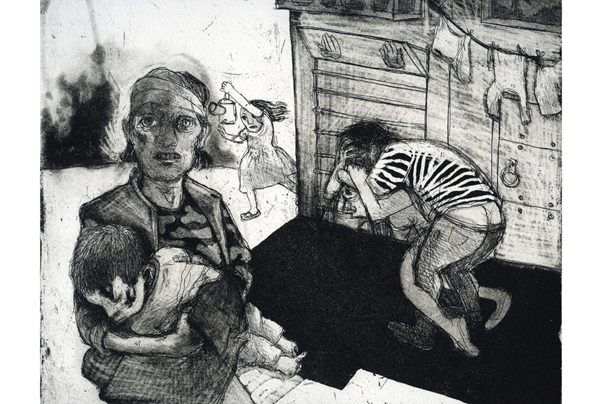

The problem for most figurative artists is not how to paint, but what to paint. This has never been a problem for Hanselaar. Her rush of ideas is kept reasonably in check in her paintings, but tumbles over itself in her prints. She took to etching quite late, in 1999, like a duck to water. ‘Printmaking made me more playful technically,’ she says; it also gave her fantasy free rein. Her first major print cycle, ‘La Petite Mort’ (2005), was a response to the end of an affair; a series of ‘midnight doodles’ drawn with a needle straight on to the plate, it was acquired by the British Museum.

Drawing, she finds, can be a coping mechanism. ‘A feeling you have in your own life you can put into a mise-en-scène; by mythologising it, it becomes something bigger than you.’ Five years later, in her ‘Ways of the World’ series, the private mises-en-scène erupted into public dramas — multicultural carnivals of sex and violence in which the figures of John the Baptist, Simeon the Stylite and a semi-naked sadhu are somehow caught up, observed by choruses of women in burkas and gangsters in homburgs. The fun of large-cast compositions, she says, is that ‘logic just disappears’.

In the past, Hanselaar sometimes culled images from newspapers while claiming: ‘I’m not a political person, but it doesn’t mean I have no awareness of things.’ In recent years, her awareness seems to have sharpened. The first sign was the appearance of African child soldiers in 17th-century Dutch dress in paintings in her 2013 exhibition Walking the Line — the Arab Spring was in the air — but it’s in her etchings that her growing unease about the state of the world has made itself most powerfully felt. Her 2017 print cycle ‘The Crying Game’ was a response to Otto Dix’s ‘Der Krieg’: a howl of protest at the different forms of violence human beings inflict on each other, it has been acquired for the collections of the Ashmolean, the Fitzwilliam and the Metropolitan Museum, New York. More recently, following the death of her only sister, she has returned to the personal in an elegiac series of paintings inspired by childhood memories of the North Sea. They will be shown at De Queeste Art in West Flanders in September.

In our compartmentalised art world, it’s perfectly possible for an artist to be represented in national collections and remain completely unknown to the general public. Before public galleries and international dealerships hogged all the review space, it used to be the critic’s job to worm out overlooked artists and introduce them to their readers. Now we’re left to discover them through their obituaries. But should we be kept in ignorance until they’re dead?

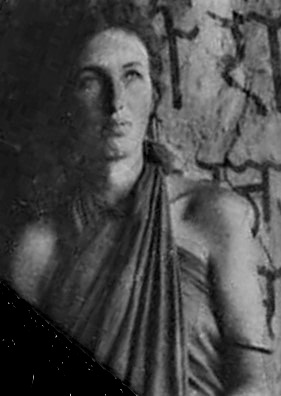

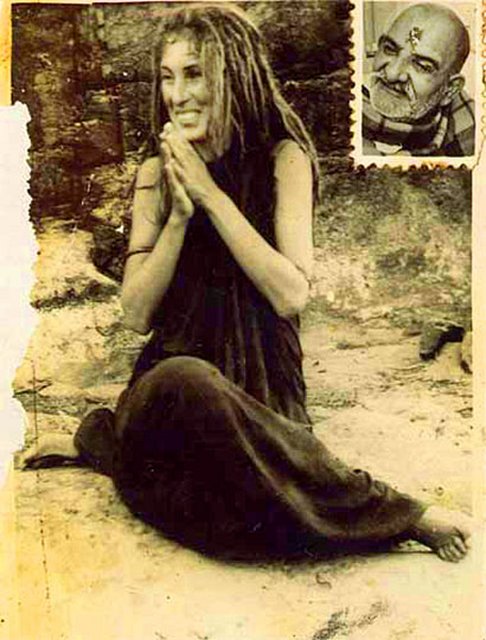

From Love Everyone by Pavarti Markus – Sadhu Uma (Marcelle Hanselaar) dropped out of art school in the Netherlands and hitchhiked to India in 1967 with her lover, Shambhu, in search of the truth that would set them free. In 1970 they returned to Amsterdam. Shambhu stayed there with his new girlfriend, while Uma hitchhiked back to India in 1971 on her own to continue her search.

I became a Giri sadhu, a devotee of Shiva, and practiced meditation and lived off what people would give me. I had great faith that I was protected by the gods, although life was often very hard for a girl who came originally from a protected background. More seriously, I had become disillusioned by the teachers I’d met over the years, the hierarchy of the monastic system, and I also began to doubt my own motivations. Therefore I decided to take a bath in the Ganges in Haridwar before leaving India.

On the bus to Delhi I met a Frenchman who showed me a small picture of a sadhu he called Neem Karoli Baba. There was something in the way that Baba held himself in that photo that touched me, so I decided to make a detour and go first to Bhimtal to pay him my respects before my farewell to India.

It was a long journey by bus and on foot, and I arrived at the temple in the late afternoon. I had not seen so many Westerners for a long time; they felt quite foreign and I was a bit intimidated by them, but they kindly welcomed me. They fed me and invited me to join the crowd for darshan with Babaji. I sat and watched, and at some point Maharajji gestured and shouted at me to come closer. He asked my name and lineage and patted me so vigorously on my jetas [dreadlocks that are “washed” with the ash from sacred fires] that ash clouds flew out. He was giggling and welcoming me. He said I could stay a while, and I made my dhuni [fire] outside the temple gates, going in for food and darshan every day.

One day he asked all his devotees what they needed. Some needed money, and he asked another devotee to give them some; another needed a blanket, and he provided that as well. At some point he asked me what I wanted or needed. My heart became very still. I bent forward till my head was against his feet and said, “I want your blessing, Babaji.” He again patted my head with vigor, ashes flying about, and then everything went still. When I opened my eyes it was evening, and I was sitting on the empty veranda in full lotus. I felt cleansed, cool, and calm. All those years I had walked about India and asked people to show me the truth; many people helped me, but I did not find what I was looking for – the reassurance it is possible to find it, to live it, to actually experience it. Maharajji gave me that experience. Because I did not have a visa or passport, Maharajji told me to go south; they would all go to the Vrindavan vihara soon as well, and I could join them there.

In Vrindavan Maharajji ordered wood for my dhunni. Wood is scarce in Vrindavan, but he respected my rules as a Girija Shaivite; my practice was not to live inside a building and to maintain a fire. Some of Maharajji’s devotees would come to my dhunni, and we talked till late in the night about our questions and quests and how each of us came to be there. Maharajji was talking to me about Chitrakut, how he had been there. I felt that after my samadhi experience I wanted to deepen my meditation practice, so I took my leave to go to Chitrakut. On my arrival I did my parikrama [circumambulation] of that holy mountain, which is the body of Vishnu, and spent the night in the only Shiva temple there.

There I met someone who told me there was a cave a few miles away where I could practice. For quite a while I had been suffering from malaria attacks and this, coupled with my being illegally in India, meant that this cave was an ideal solution for me. The cave had clean water nearby. The brother of the man in the Shiva temple was a headmaster of a nearby village school, and he generously promised to send me one meal a day, five times a week, with the woodcutters who worked on top of the mountain. I sat in that cool airy cave tending my fire, with a photo of Maharajji in a small niche near the entrance. I had few human visitors.

Then one day a very old woman came down the mountain, came into the cave without greeting me, and went straight to Maharajji’s photo. She looked at it and cackled, “He has tubes up his nose.” I was annoyed, partly by her lack of greeting and even more by her criticism of my teacher! I told her that was just a trick of the photo and that she should go. She stubbornly repeated this “tubes up his nose” line a few more times before going away. Many months later I came down from the mountain, because I wanted to pay Babaji a visit and ask him for guidance. My solitariness, sickness, and little food had given me overwhelming visions and hallucinations, and I did not know what to make of them. But when I came at last to the plains, I was met by others who told me Maharajji had died some months ago. He had been, they told me, at some point in the hospital with tubes going up his nose.

I felt he had deserted me, and I was so angry that I kicked the Hanuman murti in the temple. Sometime later I went back to Chitrakut and, following some dreams I had, went to a monastery in the jungle to ask them for advice on my meditation practice. I also went partly to follow Maharajji’s footsteps to somewhere in the jungle in the direction of Bilaspur, where Maharajji had stayed as a young sadhu for a while. I stayed in India as a sadhu till 1974, and then I returned to Europe, where I tried to incorporate all these things into my everyday life as an artist. Sometimes I am still falling down and getting up. And knowing it’s all right.

Marcelle Hanselaar – http://www.marcellehanselaar.com

Born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and growing up in the formal atmosphere of a protestant, post-war country, proved, thanks to her drop-out/turn-on rebellion, a profound source of inspiration for the recurring subject matter in Hanselaar’s work; namely the fierce and sometimes troubled cohabitation with those raw desires, secret fantasies and uncultivated instincts and our functioning in a civil society.

Although she studied briefly at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague, her lust for adventure, guided by a quest for self-discovery, led her to years of travel, until, in the early 80’s she settled down in her studio in London where she still lives.

Self-taught, she started out as an abstract painter before turning to figuration.

At the same time she became fascinated by etching, its harsh, bitten line seemed to perfectly suit her subject matter.

As an artist Hanselaar looks for ways to express those illusive questions of who and what we are when the mask is off, and how we appear when the mask is on. The shock effect of her work lies in the contrast of combining her outspoken subject matter with the conventional medium of oil painting or etching.

Both her paintings and her prints display her delight and fascination with theatrical illusions and although often peppered with a biting sense of humour, the works reveals her own vibrant understanding of human nature, in all its animosity and fragility.

Profiled by Laurence Fuller – www.laurencefuller.com