Ashrams of India: Volume 2 Chapter 21 Uttarakhand, Crank’s Ridge Former haven for hippies and mystics during the 60s and 70s

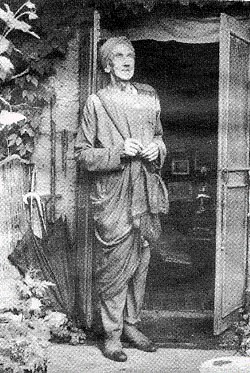

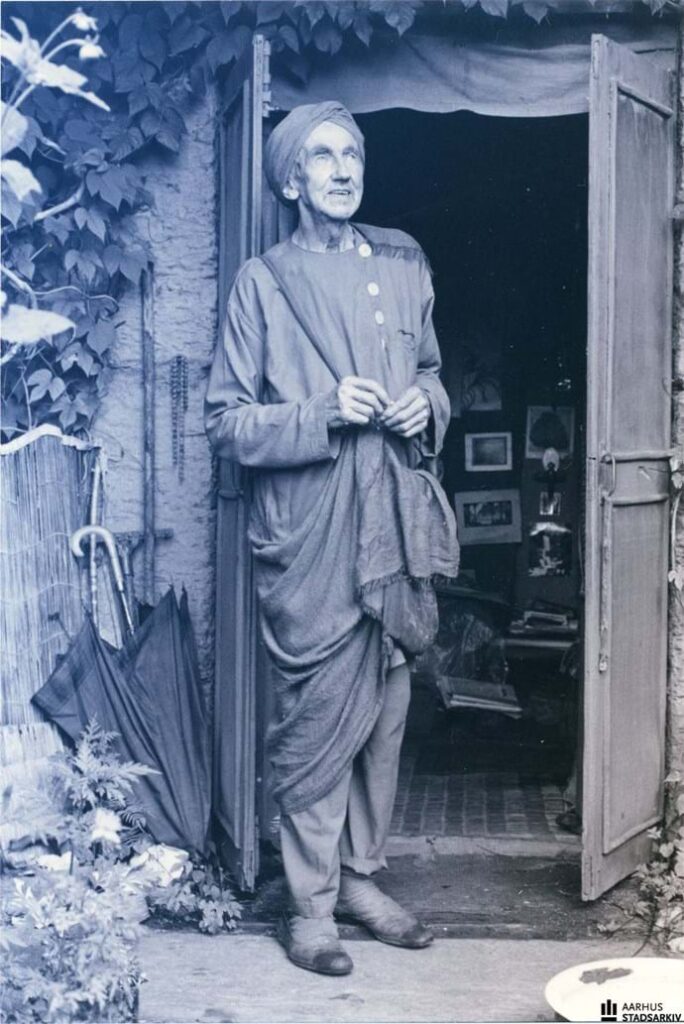

Alfred Julius Emmanuel Sorensen (October 27, 1890 – August 13, 1984), also known as Sunyata, Shunya, or Sunyabhai, was a Danish mystic, horticulturalist, and writer. He lived in Europe, India and America.

The son of a peasant farmer, he grew up near Arhus in northern Denmark. His formal education ended when he was 14 years old when the family sold their farm. He then worked as a gardener on estates in France, Italy, and finally England. While working at Dartington Hall near Totnes, Devon, England, he met Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian Nobel Laureate poet. This was in 1929. The two shared conversation on a variety of topics. Sorensen introduced Tagore to gramophone recordings he had of Beethoven’s Late Quartets, whereupon the poet invited him to his newly created university, Shantiniketan, in Bengal. Sorensen, he said, could ‘teach silence’ there.

Sorensen visited India from 1930 to 1933 and came to see the country as his home. After initially staying at Shantiniketan, he went on to travel around India visiting places of interest to him. In 1933, he returned to the west to tie up loose ends and then headed back to India where he lived until the mid-1970s. When he returned to India this second time, he began wearing Indian clothing, a style of dress he would continue for the rest of his life.

Tagore introduced him to Nehru, and in 1934 Sorensen visited the home of Nehru’s sister and brother-in-law at their house in Khali, Binsar where he stayed and used his horticultural skills in their garden. During the summer he continued to travel. It was while staying with the Nehru family that one of their friends offered him a piece of land where he could live. Called Crank’s Ridge it was near Almora.

India’s rich spiritual heritage provided a perfect environment for Sorensen’s natural mystical inclinations. During his first stay in the country he was initiated into Dhyāna Buddhism, but it was the Hindu Sri Ramana Maharshi who was to provide the biggest influence on his spiritual life. Sorensen had read Paul Brunton’s classic A Search in Secret India (1934), and soon after he actually met Brunton. Brunton arranged for his first visit to Sri Ramana.

Between 1936 and 1946, Sorensen made four trips to Ramana Maharshi’s Tiruvannamalai ashram, staying for a few weeks each time. It was during his visit that Paul Brunton told him that Ramana had referred to him as a ‘janam-siddha’ or a rare born mystic. Indeed, a profound experience occurred to Sorensen while he was on his third visit to Sri Ramana. This was in 1940. “Suddenly,” he wrote, “out of the pure akasha and living Silence, there sounded upon Emmanuel [his preferred name for himself] these five words, ‘We are always aware, Sunyata!’” He took these five words to be mantra, initiation, and name. He then used the name Sunyata, or subtle variations on it, for the rest of his life. The word “sunyata” meant “a full emptiness,” which he quite liked.

Although Sorensen, or again Sunyata, as he came to be known for the last forty-four years of his life, kept his Almora hut as his base, he continued to travel around India visiting friends and ashrams. This was especially so during the cold, Himalayan winter months. He met many prominent spiritual teachers in addition to Ramana Maharshi, including Anandamayee Ma, Yashoda Ma (Mirtola), Swami Ramdas and Neem Karoli Baba.

Sorensen lived in India as a sadhu or ascetic, subsisting on donations. In 1950 he accepted half of a grant of 100 Rs a month offered to him by the Birla Foundation, a charitable body. He accepted only what he needed. He subsisted on this goodwill and the vegetables he grew in his garden. Living on Crank’s Ridge, his neighbours included W. Y. Evans-Wentz, Lama Govinda, Earl Brewster, John Blofeld and others. Despite his notable neighbours, he put up a sign requesting silence of those who approached his small hut built into the rock.

From at least the 1930s he wrote diaries and reflections using a highly idiosyncratic and at times playful language. Oftentimes he combined English and Sanskrit, used obscure literary terms or invented his own words. In 1945 he wrote Memory, an autobiography. More of his writing is found in his Dancing with the Void. He acquired Indian citizenship in 1953.

Then, in 1973, some members of the Alan Watts Society arrived at his door, sent there by his neighbour, Lama Anagarika Govinda. They ended up asking him to come to California. “But I have nothing to teach, nothing to sell,” was his reply. “That’s why we want you,” they said. When they got back to Sausalito, they found that Watts had died in their absence, so they again offered their invitation, one of them saying later that they saw in Sorensen what Watts had been writing about all his life. Watts himself often said, “I have nothing to teach, nothing to sell.”

Consequently in late 1974 Sorensen set out on a four-month, all-expenses-paid visit to California. During his visit he ‘gave darshan’ at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, and at Palm Springs, among other places. Finally, in 1978, he moved to California for good. This was at the age of 88 and after spending nearly half a century leading a life of the utmost simplicity in a remote corner of India. Settled now in America he held weekly meetings at Watt’s houseboat SS Valejo, where he would answer questions from visitors.

Sadly, on August 5, 1984, he was hit by a car while crossing the road in Fairfax, California, and died eight days later. He was 93.

Despite denying that he had a ‘teaching,’ he expounded an Advaitic world view and maintained that he had always known that “the source and I are one.” Like Ramana Maharshi, he considered silence as both the highest teaching and “the esoteric heart of all religions.” Silence for him was the stilling of desires, effort, willfulness, and memories. This was the “full emptiness” that he took his spiritual name Sunyata to mean.

Source: Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia

Excerpted from The Mountain Path, January – March 2011. The details here differ slightly from the Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia article.

The Mountain Path is a quarterly Journal founded in 1964 by Arthur Osborne and published by Sri Ramanansramam. The aim of this journal is to set forth the wisdom of all religions and all ages, especially as testified to by their saints and mystics, and to clarify the paths available to seekers in the conditions of our modern world. The Mountain Path is dedicated to Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi.

Sunyata by James Johnson (Jai Jai).

Jai Jai attended the Chicago Theological Seminary. He spent his adult life in California working in horticulture and environmental restoration. Since retirement, he has lived for five years at Anandamayi Ma’s Patal Devi Ashram in Almora, Uttarakhand.

Sunyata was born Alfred Julius Immanuel Sorensen on a small farm near Arhus, Denmark, 27 October 1890. He left the body in Marin County, California, in 1984, at the age of 94. Between these bookends of his life, he worked as a gardener, lived for nearly fifty years in India, received his initiation and name from Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi, and was revered as a saint by many in northern India.

About seven years before he exited the stage of this life, representatives of the Alan Watts Foundation brought Sunyata to California from his Indian home in the Himalayas near Almora, Uttarakhand. The foundation would take care of all his needs as he aged. When he asked them what he was expected to do in America as he had nothing to teach, they replied that all he had to do was to ‘teach silence’. Once there, he held well-attended satsangs once a week, mostly in silence, on Alan Watt’s houseboat, the Vallejo, berthed on San Francisco Bay. That is where I met him. I thought of him then as a friend and mentor and often visited him on Saturday mornings.

On one such sunny Saturday in 1981, I sighed and told him I wished that Anandamayi Ma were still alive as I was magnetically attracted to her. He gave a start and looked at me in surprise. “But she is alive!” he exclaimed, “Though she is not in good health and isn’t expected to live much longer. You had better get over to India right away to see her. She is

the real thing; I’ve had her darshan a number of times.” Taking this almost as an order, I secured passport and visa and, having unexpectedly come into some money, I booked my trip; only weeks later I was doing pranam to Mataji in Vrindavan with tears of ecstasy pouring from my eyes. On Dusshera, her last in the body, in Haridwar I received a miraculous diksha from her through the vision of a mantra as I meditated that morning at dawn after dipping in the Ganga and through, that evening, a wonderful smile directed to me as she sat behind the Durga Murti to receive pranam from thousands of devotees.

Without Sunyata, that initiation would never have happened. Words cannot express my gratitude for his role in my spiritual unfolding. It was only years later that I came to view him as enlightened; he was credibly able to strike the spark that awakened that state in at least one other. But before that tale, let us return to the story of the young Sunyata.

Emmanuel, meaning ‘God with us’, as he thought of himself and was called in his youth, passed an uneventful and happy rural childhood, often silent and blissfully alone in nature. In his writings he describes how he largely escaped ‘headucation’ and ‘churchianity’, and successfully fought off the tumultuous rising of an ‘egoji’ in his early teens. These and other novel terms he later invented characterized his playful and joyous use of English in his speech and writing; for example, instead of such terms as ‘egoless, thoughtless or deathless’, he would always use ‘ego-free, thought-free, or death-free’ as closer to the true sentiments he felt. Moreover, he never spoke of being free of or from ego, thought

or death, but rather In them, implying a ‘joyous ease’ in conditioned existence; for Sunyata it had lost its substance, its absolute seriousness, and was now a place of leela, not maya. ‘Understanding’ was always ‘innerstanding’ for him; he thought that this transliteration would one day become part of the English language.

From the age of 14, in lieu of secondary school, he was trained in horticulture, at which he worked for brief periods in France and Italy before settling in England. There he worked as a simple gardener, often in the nursery, on a succession of large estates. His inner silence continued all the while and he nurtured his love of life by a wide reading of world literature and poetry, branching out into Buddhist, Hindu and Theosophical texts.

He was employed at Dartington Hall in Devonshire, England in his thirty-ninth year. That summer he met Rabindranath Tagore who had come to rest at the estate following a tiring lecture and reading tour in the West. They became friends, the young gardener clearly awestruck by the white-bearded Eastern sage and Nobel laureate in whom he sensed a depth of wisdom and ‘innerstanding’ of which he had only read. Tagore must have noticed something special in the younger man also; before he left, he invited him to come to India to teach silence at his university, Shantiniketan. Much to the poet’s surprise, Immanuel showed up on his doorstep the very next year, 1930. He had taken his time getting to India,

touring overland through Greece, the Middle East and Egypt on his way, revelling, as he always did throughout his long life, in the ‘delightful uncertainties’ of travel and meeting new friends all along the way. He states that from that time he never again had to work for his living; everything just came to him as needed, often in such abundance that he had to turn it away. But then he never wanted much and was content with what he had.

Never able to bear the Indian heat, he retreated to Darjeeling as garmi, the season of heat, came on. With Tagore’s introduction, he spent time with the great Indian physicist and botanist Jagadish Chandra Bose, by whom he was initiated into Chan Buddhist meditation. In 1931, after a brief visit to Europe to settle his affairs, he emigrated to India where he spent most of the rest of his life, almost half a century, mostly in the Himalayas. There, he said, he felt most at home. After Independence, he became an Indian citizen.

These early contacts led on to others; he soon met Nehru, with whom he struck up a life-long friendship. Whenever he was in Delhi, ‘Brother Alfred’, as Nehru always called him, would be invited to stay with Nehru’s family. For a year or so early on, he lived on the Nehrus’ Khali Estate near Binsar in the Himalayas. Indira Gandhi, then a teenager, when informed of his passing many years later, wrote of her fondness for him and regretted that she had hardly been able to make any sense of the letters he frequently sent them, so full were they of his bubbling metaphysical musings and his personal reconstructions of the English language; they were, moreover, written in what he conceded was an almost indecipherable ‘scribble’.

As his life progressed, through his contact with Nehru, Sunya the Silent would make the acquaintance of ambassadors, diplomats, high government officials and, at an official reception in Delhi, of the king and queen of Denmark who were delighted to meet this native son so honoured by the prime minister of India as an authentic holy man.

After a short time in India he settled near Almora where he built several stone cottages high on Kalimath Ridge very near the Kasar Devi Temple, an ancient Goddess pilgrimage site. He called his home Turiya Niwas (abode of the highest consciousness) and posted a sign in front: ‘Silence!’ This must have reduced the traffic considerably, although the naturally open Sunyata was friendly to all, communicated easily when outside his home and entertained many, presumably silent, guests over his long years on what became known locally as ‘Cranks’ Ridge’. It was so named because of all the very individualistic, often eccentric, expatriates who came to live there from this period on, many of them authors, artists and spiritually-oriented people. Swami Ramanagiri, the royal Swede who was brought so quickly to

awakening by Bhagavan, was one of his guests, whom he introduced to the Maharshi in the late 1940s.

During the winters, when his unplastered and draughty stone kutir became quite uninhabitable, he descended to the plains, where he stayed with the many people he had met. As his stature became more evident, he conducted satsang wherever he was.

Sanyasini Atmananda, of Austrian origin and one of Anandamayi Ma’s very close devotees, once told me that Sunyata had a following in India. In America, too, he had a considerable following in California and also in Chicago, where he visited annually as the guest of a Jungian psychologist. Osho conferred a Rolls Royce on him, though it is impossible for me to imagine him ever being chauffeured around in it. In Denmark, many people still honour him as one of that country’s

most famous sons and a true saint. I am always surprised how many people I meet know and revere him.

Sunyata’s most ‘Himalayan’ and transforming experience, however, came through Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. On three occasions, Sunyata travelled south from his home in the mountains to Tamil Nadu to visit Bhagavan briefly during the cool and pleasant winter. He spoke only once to Ramana, on their first meeting in 1936, in answer to some cursory questions put by Bhagavan. Thereafter, he always sat silently in the back of the hall, intuitively aware that Bhagavan’s

power was in his silence. After he had left for the north on that first visit, Paul Brunton, whom he had met at the ashram, wrote to him that Bhagavan had stated that Sunyata was a ‘rare-born mystic’, one in whom the ego never really developed and who was, therefore, always very close to realization.

One day on a subsequent visit, while meditating with eyes closed, Sunyata, then still Immanuel Sorensen, suddenly felt the full power of the Maharshi fixed on him. Bhagavan’s voice spoke to him telepathically and with power: “We are always aware, Sunyata.” From that locution, he took his initiation and his spiritual name. Though he was never looking for a guru, he recognized this moment as the crucial point in his life. He always kept a large picture of Bhagavan in a place of honour and praised his precepts as the highest Truth, Truth that he, now Sunyata, was discovering through his own awareness of the One Self. He had darshan of Bhagavan only one more time.

Sunyata, as stated previously, also had darshan of Anandamayi Ma many times, especially when she came to her Patal Devi Ashram near Almora. She gave him yellow robes to wear. On two occasions he was called in to sit silently with her in private, once at her Varanasi Ashram, an occasion which, he stated, “was a shunya darshan—a relief like death.”

Another time was when Mataji was visiting Sri Yashoda Ma at the latter‘s Mirtoli Ashram, also known as Uttar Brindavan.

Sunyata regarded Yashoda Ma almost as his own mother, often visiting her and the Englishman Krishna Prem at their beautiful nearby ashram which was dedicated to Krishna. Of that meditation with the two Ma’s, Sunyata said, “On this occasion there was inner silence for half an hour. The shunya silence is eternally here and now. The silence at Uttara Brindavan is one of my richest Himalayan experiences.”

He also spent some time with Gandhiji at his ashram at Wardha and participated in the life of the ashram. Bapuji’s simplicity and warmth resonated strongly with Sunyata. Sunyata’s silence and clear spiritual nature, his having adopted the Indian lifestyle fully, his friendship with Nehru, all must have made an impression.

Regarding Sunyata’s spiritual status, let us now return to the Awakening story I mentioned at the beginning of this article. I recently read a Danish devotee’s account of the experience of one of Sunyata’s frequent winter hosts, S. N. Bharadwaj of Hoshiapur, Punjab. The Danish devotee visited and interviewed this now-elderly man. He writes that one winter as Sunyata was just about to leave Bharadwaj’s home, he, Bharadwaj, begged him for some personal upadesha. Sunyata stared at him intensely and in silence for some time. He then intoned with great emphasis, “You…Are…That!” Bharadwaj states, “In this moment I lost body consciousness. I realized the ultimate reality—being one with that.” At some point he was conscious of arms being rubbed by hands; he finally realized they were his hands and his arms. Sunyata was gone and so was Bharadwaj’s ego. From that point those who know him said that Bharadwaj has been joyous and always smiling through all these many years. To ignite that fire of Awakening in another must one not be enlightened oneself? That, in part, is what leads me to believe that Sunyata must have been realized.

After his passing, a few paragraphs were found among Sunyata’s writings which offer some insight into his Awakening process, about which he had been silent all his life. He states:

“When different stages of sadhana were being manifested through this body, what a variety of experiences I had then! I thought that there was a distinct shakti residing in me and guiding me by issuing commands from time to time. Since all this was happening in the stage of sadhana, jnana was being revealed in a piecemeal fashion. The integral wisdom (vijnana), which this body possessed from the very beginning, was broken into parts and there was something like a superimposition of ignorance.

“In my sadhana I was told by the invisible Monitor, ‘From today you are not to make obeisance to anybody.’ Later on, I again heard the voice within myself which told me, ‘Whom do you want to bow down to? You are everything.’ At once, I realized that the universe was, after all, my own manifestation. Partial knowledge then gave place to the integral, inherent wisdom, and I found myself face to face with the Advaita One that appears as many.”

He further states that during this period many vibhuti (powers) were manifesting, though, to anyone’s knowledge, he told no one about this during his life. Sunyata seems to have had, among others, the siddhi of healing by touch. When he discovered this he was perhaps doing seva at a clinic, quite possibly that of his friend Dr. Ved Prakash Khanna, now deceased, who ran a nature cure clinic in Almora and who was the founder of the Sunyata Memorial Society. Sunyata describes how he found that whenever he touched a patient, that individual would be immediately cured. He says he tested this on a number of people and found it to be invariably true.

He must have soon discontinued this seva, because this power would otherwise certainly have become known and sensationalized. Sunyata abhorred such attention and, moreover, wrote dismissively about ‘Shakti business’ of various kinds as a distraction and as an impediment on the spiritual path. He was just not interested in such manifestations and certainly realized that their display would invariably have attracted the wrong kind of attention, complicating

his life considerably. He was clearly not averse to encouraging people on the spiritual path but he would have been appalled by hordes of miracle-seekers flocking to his humble door. That must be why he kept his powers secret and perhaps never exercised them thereafter. In his short essay he states, “…those powers are not meant for display. They should be kept carefully under control.”

Always an enthusiastic exponent of the pure, Self-revealed Advaita Vedanta, Sunyata rarely spoke of gods or goddesses and didn’t participate in religious ritual. Bhagavan and Nisargadatta Maharaj were his ideals.

And he lived his innerstanding. Near Almora I met a man, now in his seventies, who was a member of the Sunyata Memorial Society that built the simple samadhi for his ashes on Kalimath Ridge. He told me, with tears in his eyes, that he owes everything to Sunyata. He recounted that, as a troubled teen, he had broken with his family and was digging postholes for a tea-stall along the ridge road when Sunyata, whom he knew, passed by on his way to Almora market, a few miles away. Sunyata asked what he was doing and then went quietly on his way after being told. The next day Sunyata came by again and silently handed him an envelope, then left. Inside were 1500 rupees, a fortune in those days. The man has turned that gift, clearly some devotee’s guru dakshina, into a general store, a restaurant and two guest houses. With

real emotion he said, “Sunyata would let me come into his house and just sit. I loved him. He was the quietest man I ever knew.”

In August of 1984 in San Anselmo, California, Sunyata, still bright and active at 93 and dressed as always in colourful clothes and turban, was struck by a car as he stepped out from between parked vehicles to cross the street on his way to the market. He died in a coma some days later, the first time he had ever been hospitalized. An autopsy was conducted. The doctors reported that all his organs looked like those of a man half his age; he might have lived for decades more. When his time came, it took two tons of speeding steel to kill his body. He was my friend; I loved him, too. All praise and honour to the silent shining Self in which Sri Sunyata is absorbed.

Sunyata – Alfred Emanuel Sørensen – a Danish Mystic https://www.meditation.dk/sunyata.htm