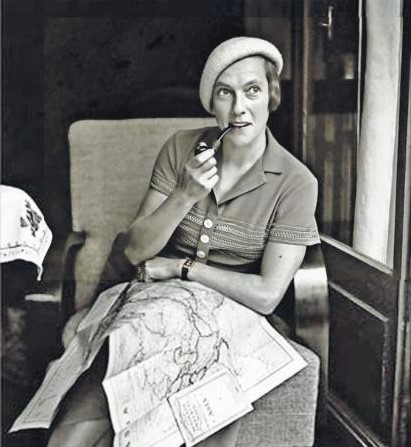

Ella Maillart was the pioneer solo woman explorer who found her spiritual side in India.

By Ravi Shankar.

The New Indian Express. Published: 27th September 2020 05:00 AM | Last Updated: 25th October 2020 11:02 AM |

A casualty of the internet and satellite mapping is the explorer. Before technology, Huen Tsang, Marco Polo and Columbus explored uncharted lands, discovered new civilisations and opened the eyes of the world to horizons beyond maps that warned seafarers that if they sailed far enough, their ship could fall off the earth because it was flat.

All legendary travellers were tough men. Not Ella Maillart, one of the greatest travellers of the 20th century.

On the 90th anniversary of her first adventure in the 1930s, the Swiss woman is a gender statement to the lost world of dangerous curiosity—exploration. Maillart moved to India through Iran and Afghanistan. She spent the World War II years in India, staying in Tiruvannamalai near Madras close to Ramana Maharshi ashram.

It was in India where she discovered her spiritual side, which had begun with her fascination with the Orient.

She became a follower of Sri Atmananda Krishna Menon in Kerala, who founded the Direct Path philosophy.

In her autobiography, Cruises and Caravans (1942), Ella writes, “I began this journey by exploring the unmapped territory of my own mind.” She was an action junkie since early youth, representing Switzerland as the only woman competitor at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

Adventure coursed through her blood—she played a stuntwoman in German mountain films and an actress in a skiing movie. Her first serious trip was in 1922, taking a 21-foot boat from Cannes to Corsica when she was hardly 20.

She sailed with four girls following the trail of Ulysses to Ithaca. For a couple of years, carrying just a backpack, she set off solo through Central Asia, Turkestan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and cities such as Tashkent, Samarkand, Khiva and Bukhara previously unknown to the West.

Stalinist Russia was a dangerous place for a woman. Alone, she skied up the Mountain Sari Tor. She travelled to the Caucasus and discovered the hidden valley of Svanetia.

All through Central Asia, where men regarded an unmarried woman as available, she took along syphilis medication in case she was raped; the acceptance of which, as motorcyclist traveller Heather Philips wrote,

“By re-framing such a destructive act of violence, she felt powerful. She didn’t shrink from the darkness, she leaned in.”

Well-known Indian women travellers like Shivya Nath and Rutavi Mehta revel in travelling solo. In the UK, 75 percent of Gen Z women have been backpacking or planning to set out.

Maillart, the pioneer of solo woman travellers, was the first to break the glass ceiling by courting danger and discover the unknown at a time when women wore skirts, not trousers.

Another article from archive.arunachala.org;

The Cat on Bhagavan’s Couch

by Ella Maillart

PART I The following is taken from the book Ti-Puss written by Ella Maillart of Switzerland and published in 1951. She sent the copy found in Sri Ramanasramam’s library to Swami Viswanatha with the inscription: “For you, Viswanatha, so that you may sometimes remember your friend, the Daughter of the Mountains.”

Ti-Puss by Ella Maillart. “Her full name was Mrs Minou Wildhusband, née ‘Ti-Puss (pronounce Tea Puss) Push-i-kin.” Self-pity had made me want a pet. I had come to Tirùvannàmalai in order to live near a Sage who embodied the essence of Hindu wisdom; and whereas a course for beginners would have suited me best, I found myself stumbling about in the aridity of Vedantic lore, listening all at once to the highest metaphysical teaching. Besides, I had just ended the drudgery of writing one more book about my Central Asian journeys; and my sentimental self claimed as a reward a living toy I could fondle when I wanted to banish Reality from my preoccupations. I wanted to smile again!

ELLA Maillart was an early 20th Century pioneer among women adventurers. Strong, ever curious about the unknown and fascinated with travel she sailed over seas and journeyed with caravans, on foot and seated on animals, throughout remote areas of Chinese Turkestan, the Caucasus, the Tien Shan Mountains, Russia, Mongolia, Tibet, etc. She realized that the only way for her to make a living was to write about her experiences. During World War II she remained in India from 1939 to 1944 and resided mostly in Tiruvannamalai, understanding, at last, that the ultimate adventure and real journey is to make the inner one to the realization of the Self.

Ti-Puss appears on the surface to be a frivolous book about Ella’s infatuation with a kitten. But in the book one finds hints here and there about her inner experience and understanding of all things that she absorbed while living in the presence of Bhagavan Ramana. Ella wrote: “ The teaching says: ‘It is for the sake of the Self that all things are dear,’ though we usually think it is for the sake of the loved object. This cat, so alive in me that she has become like part of me, opened my heart where love was dormant… ‘Love being the real Self.’ When my feeling of love becomes uppermost for an extremely short while, there is neither cat nor any limited individuality. I am lost in love-impersonal, love which is a state where time has no power.”

After the war and her return to Switzerland, Ella settled into a villa which she named Achala, in one of the highest villages in the Swiss Alps. She would occasionally arrange cultural tour groups to Asia. To her travel companions she would often say: “Ask yourself unceasingly, ‘Who am I?’ and through this constant inquiry you will come to know that you are the Light of Consciousness.”

For devotees who are cat lovers and have been uncertain about the Sage’s opinion of these four-legged denizens of the dark, read on and take heart. Bhagavan’s love embraces all. Ella writes:

In the neighborhood of the Ashram, I was fond of three different walks – the mountain, the lagoon and especially the grove of Palakottu adjoining the garden of the Sage where the sadhus lived in their miniature huts. Every afternoon, loudly and endearingly, the cat insisted on my taking her for an outing, galloping off excitedly and then returning to me! I think she greatly enjoyed our hide-and-seek promenades and her slight fear when we discovered new paths.

But, honor to whom honor is due, the cat called on the Sage! One early morning I found her near me as I was leaving my sandals by the door before entering the hall. She must have crossed the road behind me, and passing among the tombs of holy men, followed me by the old tank with the many stone steps leading to the water-level. I let her do what she wanted. As I greeted the Maharshi by joining hands, my cock-sure Ti-Puss jumped on the couch where the Sage spends all his time. Particularly kind to animals, feeding the squirrels, peacocks and monkeys coming to him, as well as Lakshmi the oldest cow of the ashram who was fond of bananas, the surprised Maharshi put his newspaper aside, smiled at the thin kitten and touched her head. I am sure she would have played with him, because all animals behaved with him as if he ‘belonged’ to them; but the fussy Brahmins sitting near the couch frightened her away with their shawls, though they heard my saying: “This is my faithful companion, back from bathing in the Ganges!”

From a bold charmer, tail upright and full of good intentions, she became a hateful mass of cringy fur.

“Why do you do that?” I asked the men.

“Because it will run after the squirrels and kill them!” As usual the Maharshi was not interested in the variance of opinions around him. His concern was to give answers, in Tamiḷ and Telugu, seldom in English, to the philosophical questions put to him by visitors, or sometimes to correct the Sanskrit recitation of a devotee.

An hour later when the inmates received their mail from Rajah the Postmaster, my share included the first copy of Cruises & Caravans which I had dedicated to the Maharshi. I then presented that copy to him, feeling suddenly ashamed to have written that story very perfunctorily.

The dust-cover showed the house of my childhood by our lake, with many racing yachts at their moorings with sails hoisted. [Ella Maillart had represented Switzerland in sail boating in the Olympics when young. She was also a world-class skier.] When the long and elegant fingers of the Sage framed that beloved bay which had cradled my dreams, I saw that the dreams of those days had led me very slowly to the feet of his all–embracing knowledge.When Viswanatha, the young sadhu who was my friend, came in, “Have you seen Ella’s book?”, the Maharshi said, handing it over to him. The sage seemed pleased: when he looked at me directly but with his ‘impersonal’ stare, once again I thought that I had never seen a forehead with equal width, light and refinement….

PART II We express our sincere gratitude to Aine Keenan for generously sharing all her research on Ella Mailart and Marye Tonnaire both of Sri Ramanasramam – who enthusiastically provided us with a smooth and concise English translation of Ella’s French interview and the last chapter of her book Croisieres et Caravanes.

IN our last issue, in the article “The Cat on Bhagavan’s Couch”, we introduced an exceptional personality of the 20th Century who had taken refuge in India from 1940 to 1945, while the Second World War raged through most of Europe and Asia.

This was Ella Maillart, an early pioneer among women adventurers, strong, ever-curious about the unknown and fascinated with travel. She had written a half dozen books about her travels and another series of books has been published about her since her passing in 1997 at the ripe age of 93.

After she left India and returned to Switzerland, Ella settled into a mountain chalet high in the Alps and named it “Achala”, abbreviated from Arunachala.

Wherever she traveled throughout her long life she took photos, notes and even films. These chronicles of life in some of the most remote regions of the world have been recognized as valuable historical documents, and her fearless spirit of adventure inspired women and men around the world.

While at Ramanasramam in 1942 she wrote Cruises and Caravans; though autobiographical, the book primarily chronicles her 1935, 3,500-mile trip west from Peking through the Taklamakan desert and Sin-kiang (at that time closed to foreigners) to Kashmir: a journey which took seven months. While in Tiruvannamalai she received a copy of the book from the publisher, which she immediately showed to Bhagavan, a happening that we described in our last issue. Ella later formally presented the book to the Maharshi with the following inscription:

Dear Bhagavan,

Here is the book you helped me to write the summer before last. It is a ‘war production’ intended for young readers, and you may remember that the publishers sent me, as a sample for that series, the book by the mountaineer named Smythe.

Once more I form the deep wish that after so many years of dealing with the external world – as you may see by glancing through my autobiography – I shall now make swift progress in discovering the inner life leading to You.

Yours – Ella

Sri Ramanasramam, 9-2-43

With the publication of this book, Ella’s financial situation improved and a career as a writer, lecturer and travel guide appears to have been established, though she did not leave India for another two years. The book was also later published in French. In the French edition she added one more chapter in which she shared with the public her spiritual journey, a journey that began in her youth but ended at the feet of the Sage of Arunachala.

Ina French-filmed interview (see MOVIE REELS for the interview) at her Swiss Alps chalet in 1973, Ella talks about her time with the Maharshi “During this time I was thinking of the war in Europe, and with feelings of despair, I felt pressed forward to go to this Sage whose address I already had.”

Holding in his hand one of the photos Ella had taken of Bhagavan, the interviewer asked her if this was the first sadhu she had met. Ella, in general terms, explained to the interviewer what a sadhuis:

“A sadhu is a master who has found the truth; he is not looking for it, and all of his answers come from an inconceivable level of consciousness. Never would any of us reply as he did to all the varieties of questions that one would ask him. I decided to stay with him for quite a long time and then, after two years, I stayed with another master, another sage who was in Kerala (Krishna Menon) and who taught the same method of introspection – “Know Yourself”. Try to know who is the true Self, the ‘I’ – with a capital ‘I’ – and not the little ego. And in Kerala I also stayed a very long time, more or less until the end of the war.”

Then the interviewer, apparently a little puzzled, asked what were the questions to ask a sage and what it meant to live with a sage. Ella went on explaining, “Well, the basic question I asked myself since my childhood when I would see something while living at the Creux de Genthod (name of the place where she lived near Geneva) was: ‘What is Reality, the center, the essence of what we see; the essence of life in the present moment?’

“I knew that the present is the only ‘Real’ thing, but then again it’s just a word used to give a response. Well, with that understanding, when we want to get to the bottom of a problem, we have to know who we are, because everything depends on me. I am the one who is conscious and who sees things. And all the questions that one asks a sage revolve around that one fundamental question, ‘Who Am I?’ Who is the Real I? All of the wisdom in the whole world speaks of two ‘I’s’, a little ‘i’ who is identified with the body and an ‘I’ who refers to the Supreme ‘I’. And it is necessary that the two ‘I’s’ coalesce to form only one (merge into one), so that we are not perpetually divided in ourselves. And the true Master is one who has accomplished this Realization directly, the direct experience of the True ‘I’. He is capable of responding to our questions in such a satisfying manner that we say, ‘Voila! He is a Master,’ I understand his responses, I like the way he responds, and I will stay close to him to progress and refine myself so that I too will be able to reach his level of consciousness, if that is my destiny.

“So we stay close to such a sage, though most of the time he may respond in silence, without saying a word, by a kind of telepathy. And most of the time he foresees our questions. He gives us books, he helps us with readings, and we can ask questions when we have not understood something. And it’s this inner work that is worthwhile. Then we become so passionate about what we find within ourselves that we accept all the difficulties of living there in the extreme heat with unsuitable food and crude accommodations.”

Then the interviewer asked whether she succeeded in coalescing the two ‘I’s and, if so, why did she return to Switzerland rather than stay in India.

Ella: “Well, you speak of the supreme goal as if it were very easy to obtain. I think that I understood (the concepts), and equally the techniques that they gave me. And if I actually did understand something worthwhile, I should be able to put it into practice as well here (in Switzerland) as over there. The climate there is something really extreme and the food didn’t agree with me at all. And I think if one is born in a certain place, it is in that place one must accomplish one’s life and one’s destiny But I went back many times to the Sage (The Maharshi), up until his death. After the war I went back three or four times and in 1951, I spent four or five months….”

These visits to the Ashram that Ella mentioned in this interview do not seem to have been recorded earlier. She may have also visited Krishna Menon (Atmananda) in Kerala, with whom she had spent considerable time during the war years. He passed away only in 1959. He had no formal ashram and lived with his family in their Trivandrum home.

In the interview, filmed in her chalet study, two photos, the Welling bust photo of Sri Ramana and one that she herself had taken of Bhagavan, are prominent. By all evidence it was the Maharshi whom she connected with and revered most, and it was his teaching she practiced throughout her long life.

In the course of Ella’s natural, spiritual maturing process, which no doubt was accelerated in the Maharshi’s proximity, her relentless restlessness subsided with the realization that “The world with its countless aspects cannot give us the fundamental answer: only God can. And God can be met nowhere but in ourselves . . .” So when she returned to Switzerland in 1945 Ella settled down to a quiet life, though her fame continued to grow from day to day. A glimpse at the Index of Ella’s Geneva Archives reveals a prolific correspondence with renowned writers, thinkers and political figures of the 20th Century, including Winston Churchill, Teillard de Chardin, Alexandra David-Neel, Arnaud Desjardins, André Dupré, Olga Tolstoy, Titus Burkardt, Krishna Menon, Edwina Mountbatten, Pierre, Prince of Greece, to name a few. A little closer to home, the archives have folders of correspondence between Ella and Chinnaswami, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Major Chadwick, Guy Hague, Henri Hartung, Wolter Keers, Jawaharlal Nehru, Ethel Merston, and Swami Siddheswarananda.

PART III With this final installment we conclude our short description of the life, aspirations and realizations of a woman who in the early 20th Century gained world-wide fame from her fearless adventures in the remotest parts of the globe. Ella Maillart’s incessant desire to discover uncharted territory ultimately landed her at the feet of the Maharshi where she realized that the true journey and destination is the discovery of the ever-present Self within.

AfterMaillart’s return to Switzerland she was requested to send an article for Bhagavan’s 1946 Golden Jubilee Souvenir, which she titled, “The Sage’s Activity in Inactivity”.

In the article she advances many insights about Bhagavan’s exalted state and his ultimate beneficence to the whole creation, which can so easily be misunderstood by the Western savants. She begins her contribution with the following remarks:

“According to my actual understanding it would be foolishly daring of me to write something about Sri Ramana himself, the mode of life of a sage being an abysmal mystery but for those who enjoy a similar state of consciousness.

How and to whom can be described what is experienced within by one who is desireless, whose sorrow is destroyed, and who is contented with repose in the Self?— Ashtavakra Gita

“Neither can I be so bold as to add my gloss to the commentaries that have already been made on the Maharshi’s “Forty Verses”. Who am I to do it? Would it be of any help to anyone, and is it not much better to let Sri Ramana, the Teacher, comment on them himself, if and when he thinks it could be of any use?

“As for descriptions of the life at the Ashram in Tiruvannamalai, I don’t think it is within my power to depict the subtle atmosphere which renders the place unique in its setting of dry and hard beauty.

“Nevertheless, I would like a small token of homage to reach the feet of Sri Ramana from me as a pledge of my gratefulness.And he will perhaps be indulgent enough to accept the following lines about a thought that occurred to me.”

After her return to Switzerland she added an additional last chapter to her French edition of Cruises and Caravans. In it she openly reveals her lifelong spiritual aspirations and how the few years she spent in India resolved all her doubts and led her to the path of Self-Enquiry of “Who Am I?” Excerpts from this chapterfollow.

Chapter XIV South India

“Since book learning never really suited me, my idea was to take some time living with a sage whose behavior would oblige me to grasp what eluded me intellectually. I learned about two seemingly genuine spiritual masters from two French friends who were familiar with India.

“The world attracts us by its marvels and by its adorable beauty even before we start to feel that, indeed, it has a hidden meaning. We start to study it; we go off to conquer it, looking for whatever satisfaction it could bring to our deepest desires.

“But none of the multiple aspects of the world can give us the fundamental answer. That can only come from God, and where else is God other than within us. Everyone has to discover this (fundamental) truth on his own. The spiritual being, hidden within us, is the living source of our deepest aspirations, and those aspirations will never be fulfilled unless (the deeper being) is liberated. In many of us, it is impotent, paralyzed because it has been neglected, and the power to bring it back to life lies within the heart and not in the brain. I am not saying all this because someone taught it to me, but because I have experienced the truth. In my view, it is the most important truth that has emerged from everything that I have seen or understood; it is the sum of all my discoveries. Today I feel fulfilled, and even though I live alone, never again will I suffer from loneliness.

“India for me was the beginning of a completely new voyage that would lead me to the full and harmonious life that I was instinctively looking for. To undertake this journey, first I had to understand the “unknown lands” of my own spirit.

“I was lucky enough to make a few hundred rupees from the screening of my film on Afghanistan in Bombay. I had taken leave for 18 months so I could try to live like a Hindu in the south of this great country. That would give me enough time to decide whether Hindu wisdom (actually) suited me.

“I made several brief trips to Pondicherry where I went to visit Sri Aurobindo twice, but for a few minutes only and among several hundred disciples. The rest of the time the master would retire to his room on the first floor of a large, grey house surrounded by a flowery courtyard. This was not what I was looking for, and his method seemed too difficult for me. On the other hand I wanted to prolong my stay near the sage Ramana Maharshi. His life was public. Anyone could approach him, ask him questions and enjoy the benefits of his presence that radiated goodness, distinction and immutable peace.

And there each one of us was free to do whatever he wanted, because, with the exception of meals, there was no set of rules for community life. I got into the routine of staying for two hours each morning and each evening in the hall where around twenty people of both sexes were seated on the ground, legs crossed in silent meditation.

I read the little brochures where the main responses of the sage had been collected over the course of some thirty years. His function was to inform seekers about the nature of the ultimate reality. And I tried to see if his replies corresponded with something I felt in myself.

While reading his mail or the newspapers, correcting proofs, fanning himself or meditating, the Maharshi would sometimes look at us or would smile at the astonished children who stood there like pillars in front of him. He would often give nuts to the agile squirrels perched on the top of his sofa, and of course, his favorite cow would drop in to ask for a banana.

Morning and evening a group of Brahmins chanted the Holy Scriptures. At a fixed time the sage would take a short walk in the surrounding area, and it was on these occasions that we could speak to him in private. At eleven o’clock we would all eat in his presence, curry-rice served on banana leaves spread out on the red-tiled floor. The right hand alone was used to carry the food up to the mouth.

According to the rules of caste, the Brahmins ate apart, separated by a screen. The Maharshi was seated so as to see everyone; he had been born a Brahmin, but because he was a sage, “liberated while alive” as they say in India, he was beyond all caste observances.

The ashram was about 15 minutes from the little town of Tiruvannamalai where I had rented a tiny room for five rupees a month. At night I would unroll my sleeping bag on the terrace since my room was stifling due to the hot sun of the day. Each day I would leave the town and go to the ashram, sheltering myself from the blazing sun under a black umbrella like a well-to-do Hindu. Each day I would meditate and listen to the An Ella Maillart Photo telegraphic answers given by the sage, or else I would simply notice that some of my problems were disappearing even before I could formulate them. It was as if they were resolving themselves. I often consulted two of the disciples who knew English very well when I wanted to understand a classical text or again to clarify some statements that appeared to be contradictory.

We can never know That by which we know. However, That is the only immovable element underlying all of our changing experiences! It Is That which allows us to feel the fullness of a mysterious reality within. If we fear that the world of the senses is either going to fascinate us or disappoint us, there is no use in becoming an ascetic who renounces everything through sheer will power. But armed with patience we must, on the contrary, continue to live a normal life and at the same time inquire into the nature of this ‘I’ that surges up each time we say, “I think,” “I ask,” “I feel,” “I am.”

Meanwhile, I was reading lots of other things but they didn’t help me enough. What counted above and beyond everything else were the eyes of the Maharshi when he looked at me, a look so noble and so magnificent that one had to ask oneself what was he seeing!? So, something cracked in my heart, my thoughts stopped, and a grateful certitude accompanied by a wave of love flooded my chest. Finally I was able to love without any restriction…to love without asking for anything in return…to love for the joy of loving.

These brief and rare moments gave way to dry and critical thoughts, but they also gave me patience and courage.

All I had managed to understand was that for most Westerners, harmony, love for one’s neighbor and wisdom are inaccessible as long as the most important part of us continues to be ignored or else smothered by our secular lives which are focused solely on obtaining a security that cannot exist on the material level.For the first time I can accept this without fighting it, because I have started to understand the absurdity of our world and the absurdity of the efforts that up to now I had blindly made to try and reach deep harmony.

Ella Maillart (or Ella K. Maillart; 20 February 1903, Geneva – 27 March 1997, Chandolin) was a Swiss adventurer, travel writer and photographer, as well as a sportswoman.

Early life

An only child Ella Maillart was born to a wealthy fur trader from Geneva. Her father was Swiss her mother Danish. At the age of 20 she and a friend sailed from Cannes to Corsica, then to Sardinia, Sicily and Greece. She competed in the 1924 Summer Olympics as a sailor in the Olympic monotype competition where she was the only female competitor and finished ninth out of 17. At this time she was also the captain of the Swiss Women’s land hockey team and was an international skier. [1]

Career

Ella Maillart in Iran 1939/40

From the 1930s onwards she spent years exploring Muslim republics of the USSR, as well as other parts of Asia, and published a rich series of books which, just as her photographs, are today considered valuable historical testimonies. Her early books were written in French but later she began to write in English. Turkestan Solo describes a journey in 1932 in Soviet Turkestan. Photos from this journey are now displayed in the Ella Maillart wing of the Karakol Historical Museum. In 1934, the French daily Le Petit Parisien sent her to Manchuria to report on the situation under the Japanese occupation. It was there that she met Peter Fleming, a well-known writer and correspondent of The Times, with whom she would team up to cross China from Peking to Srinagar (3,500 miles), much of the route being through hostile desert regions and steep Himalayan passes. The journey started in February 1935 and took seven months to complete, involving travel by train, on lorries, on foot, horse and camelback. Their objective was to ascertain what was happening in Xinjiang (then also known as Sinkiang or Chinese Turkestan) where the Kumul Rebellion had just ended. Maillart and Fleming met the Hui Muslim forces of General Ma Hushan. Ella Maillart later recorded this trek in her book Forbidden Journey, while Peter Fleming’s parallel account is found in his News from Tartary. In 1937 Maillart returned to Asia for Le Petit Parisien to report on Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey, while in 1939 she undertook a trip from Geneva to Kabul by car, in the company of the Swiss writer, Annemarie Schwarzenbach. The Cruel Way is the title of Maillart’s book about this experience, cut short by the outbreak of the second World War.[1]

She spent the war years in the South of India,[2] learning from different teachers about Advaita Vedanta, one of the schools of Hindu philosophy. On her return to Switzerland in 1945, she lived in Geneva and at Chandolin, a mountain village in the Swiss Alps. She continued to ski until late in life and last returned to Tibet in 1986.

Legacy

Ella Maillart’s manuscripts and documents are kept at the Bibliothèque de Genève (Library of the City of Geneva), her photographic work is deposited at the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne, and her documentary films (on Afghanistan, Nepal and South India) are part of the collection of the Swiss Film Archive in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Books by Ella Maillart

- Turkestan Solo – One Woman’s Expedition from the Tien Shan to the Kizil Kum (her journey from Moscow to Kirghizstan and Uzbekistan in 1932)

- Forbidden Journey – From Peking to Cashmir (her trek across Asia with Peter Fleming in 1935)

- Gypsy Afloat (an account of her years at sea)

- Cruises and Caravans (autobiographical narrative)

- The Cruel Way (from Geneva to Kabul with Annemarie Schwarzenbach)

- Ti-Puss (the story of her years in India with a tiger cat as her companion)

- The Land of the Sherpas (photographs and texts on her first encounter with Nepal in 1951)

In French

- Parmi la jeunesse russe – De Moscou au Caucase (about her stay in Moscow and crossing the Caucasus in 1931)

- La vie immédiate (Ella Maillart’s photographs and texts by Nicolas Bouvier)

- Ella Maillart au Népal (photographs taken in 1951 and 1965 during a trek to the base camp of Mount Everest)

- Cette réalité que j’ai pourchassée (letters to her parents, 1925–1941)

- Ella Maillart sur les routes de l’Orient (the most evocative photographs she took during her travels)

- Chandolin d’Anniviers (photographs and texts about her mountain village)

- Envoyée spéciale en Manchourie (a series of articles written in 1934 for the French daily Le Petit Parisien)