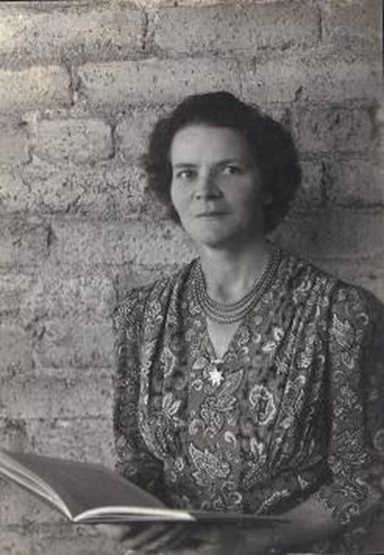

A Tribute to Jyotipriya (Dr Judith M. Tyberg) May16, 1902 – October 3, 1980.

Text by Mandakini, Photo layout and design by Anie Nunnally.

“By heaven’s illuminings one perceives her to be a bearer of the Truth.” Rig Veda, 111.61.6 Hymn to Usha

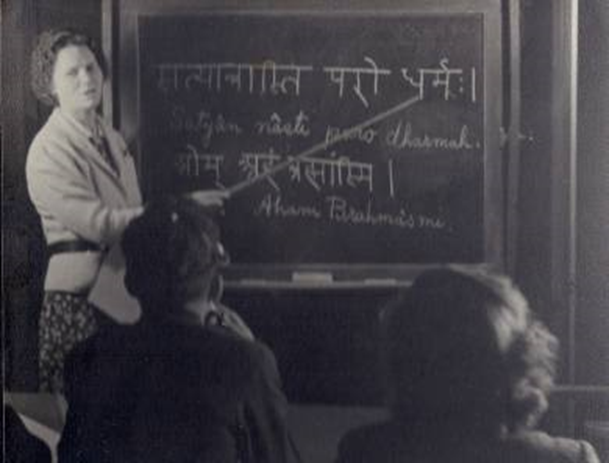

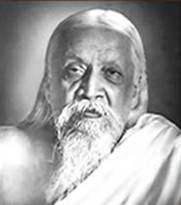

ONCE Jyotipriya asked the great Sanskrit pandit Kapali Sastri if she could study chanting with him during the few months she would be at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1949. Sastri replied that it was usual to first study with him for fifteen years before beginning to learn to chant. “Well,” she said, “I know music and I know Sanskrit somewhat.” So, the pandit referred the matter to Sri Aurobindo. The Master’s reply: “Teach her anything she wants to know, she’s going to do good work in America.” And, for the past thirty years – as the founder and life-spirit of the East-West Cultural Centre, as an inspired and devoted teacher of Indian languages and philosophy, as a noted Sanskrit scholar and author, and as a blazing guide on the path of the Integral Yoga – Jyotipriya lived the truth of Sri Aurobindo’s words. Jyotipriya was a beacon to all she met, her life an example of consecrated service to the Divine. She left her body on the 3rd of October, 1980 at the age of 78. This article is offered in gratitude to her, the one Sri Aurobindo had named “the Lover of Light.”

Jyotipriya loved to talk about the course and events of her life, not from any sense of ego, for she was an extremely modest person, but because it was a way to illustrate the workings of the Grace, and the presence of the guidance that was with her from the start. Born in California in 1902, of Danish parents who were Theosophists, she grew up in a spiritual atmosphere altogether rare in the West, and especially unique for its time. The place was Point Loma, called “The California Utopia” – the newly founded world headquarters of the Theosophical Society, begun by Katherine Tingley, then leader of the society.

There, on rolling, wild-flowered hills, set against the Pacific Ocean majesty, twenty-six nationalities gathered to share the religious and intellectual heritage of all continents and ages. Her parents were serious students of Oriental philosophy, and the Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita were major influences in their lives. All throughout the nine months of Jyotipriya’s gestation in the womb, her mother chanted a Vedic hymn to the newly embodied soul. At an early age, Jyoti could recite sections of the Gita by heart.

Within this atmosphere, that taught first and foremost that “Life is Joy,” it was Jyotipriya, or Judith as she was then called, who stood out as the happiest child. Her zest for life was such that she was nicknamed, in anticipation of Sri Aurobindo, “Judy Sunbeam.” But hers was also a serious nature, so she had another name as well, “The Little Philosopher.” While other children played on the beach, Jyoti could be seen engrossed in a book on Lao Tse, borrowed from her teacher. Other times she was found reciting her own compilation of uplifting quotations to her dolls. There, in the heyday of the Point Loma experience, she found sweet nectar for her aspiring soul. Throughout her life she would often recall precious moments of inspiration from those early years: the dawn assemblies of young and old in the open-air Isis Theatre, where they would gather to recite from the sacred scriptures, “Light on the Path” and the Bhagavad-Gita… the march together in silence to the dining hall where the passwords were “Truth, Justice, Wisdom”.… and against the chime of seven bells, the children’s bedtime prayer that invoked, “Let us seek more power of thought for self-conquest; let us seek more knowledge, more light.” From the beginning, Jyoti and the other Point Loma children were taught about the higher and lower natures, karma and reincarnation. And when Madame Tingley spoke on these “higher lines,” Jyotipriya would be moved to “great heights of inspiration.”

Jyotipriya’s upbringing had many parallels to that which the Mother envisaged as ideals for childhood education. The children grew largely apart from their parents, among young companions from all parts of the globe. There was attention placed on self-discipline and team-work. They were taught that theirs was the responsibility for their own unfoldment. And their days were filled with a host of intellectual, dramatic and fine arts activities. At the Point Loma Raja Yoga School, Jyoti became accomplished in piano, violin, viola, pipe organ, played in the orchestra and sang in the chorus. “The meaning of Raja Yoga was always made very clear to us,” Jyoti later recalled. “Madame Tingley interpreted it as the balance of the mental, moral and spiritual faculties. And in that balance, there was a great emphasis on physical education.” That is partly why Jyotipriya immediately felt so at home in the Ashram when she first arrived in 1947: “The similarities of our training and the memories came to the fore”, but “the spiritual life in the Ashram was much loftier. Ours had been more ethical and service-oriented.”

From the beginning, Jyotipriya knew that she was going to teach and help others. She described her life aspiration, as early on as she could remember, as one of “Long service, in search of truth, beauty and joy to share with all.” The idea of brotherhood, that “we were all one”, fascinated her. “There was such a sense of separateness around and I wanted to understand it, to really work it out. I loved being united with people, creating something beautiful.” All of her being was moved to a vision of “an education that could inspire one to unfold the higher nature, to express the noble and brotherly acts to produce harmony in life.” As a child, she was always observing her teachers and making mental notes as to what she would or would not do when she became a teacher herself. A born leader, Jyoti had charge of tutoring backward classmates in their studies and the responsibility for introducing new students from abroad to Point Loma life. While still a teenager, she began to formally teach in the Raja Yoga School. Later, she taught in the High School and the Theosophical University. As Hostess of that institution, she planned the educational events for the constant stream of international visitors to whom Point Loma had become a spiritual magnet. She was Assistant Principal of the Raja Yoga School from 1932-1935 and held the post of Dean of Studies of the Theosophical University from 1935-1945.

As a teacher, Jyotipriya brought an intellectual background of scope and brilliance that matched the intensity of her soul’s call to serve. She received a B.A. from the Theosophical University in Higher Mathematics and Languages, having studied French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, Swedish, Danish, Spanish and Dutch. Then, from the same university, an M.A. in religion and Philosophy, with a specialization in Oriental Thought. After research in Sacred Scriptures and Ancient Civilizations, she received the religious degrees of B.Th. and M.Th. In 1930 she began the study of Sanskrit under Dr Gottfried de Purucker and was granted the Theosophical University’s Ph.D. in Sanskrit Studies. Largely as a result of her Sanskrit correspondence courses, Jyoti was invited to lecture at Theosophical centres throughout Europe and Scandinavia in the years 1935-1936. It was during a public lecture on this tour, that a British blue-collar worker, dazzled by Jyotipriya’s intellect and breadth of knowledge, was prompted to ask: “For such a young kid, how can you have so much wisdom?”

Long before Jyotipriya knew of Sri Aurobindo or had made his saying “the Knowledge that unites is the true Knowledge” the foundation stone of the East-West Cultural Centre, she had an inherent belief in that great teaching. It was while lecturing in Europe in 1935 that her traveling companions disclosed that they were working with Hitler and tried to enlist Jyotipriya in their cause. “I was interested in brotherhood and when they proposed that Nazi stuff to me I had no use for it at all,” she later said. And reflecting on that and other incidents in her life she continued, “People were always trying to lead me to this or that, but nobody could lead me. Nobody could get me off my interests along the higher lines and my spiritual goal.”

In America, together with Dr Purucker, Jyotipriya and a select group of scholars committed to print the meanings of all the Sanskrit, Greek, Hebrew, Tibetan, Zoroastrian and scientific terms used in Theosophy for a proposed Encyclopaedia of Theosophy. Through all the learned discussions in her midst, Jyoti received an invaluable education in spiritual literature and terminology. Her contribution in return was the exposition of over 2,000 terms. Then, she began an intensive study of the Bible in the original and the Kabbalah. But it was Sanskrit that became her passion and life’s work. In 1940, Jyotipriya was appointed Head of the Sanskrit and Oriental Division of the Theosophical University. She became a member of the American Oriental Society, and in 1941 her first Sanskrit textbook, Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion, was published, climaxing eleven years of concentrated study.

Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion, which presented the meanings of over 500 Sanskrit terms used in religious and occult literature, as well as a practical pronunciation guide to and history of the language, was a “first” in its field by virtue of both its content and the technology involved in getting it to print. Set in Devanagari, it was the first occasion for that ancient script to be printed by linotype. Even in India it was only the contemporary version of Sanskrit script that was available in a linotype keyboard. By adapting a modem Indian Sanskrit keyboard, Jyotipriya and Geoffrey Barborka of Point Loma designed a special Devanagari linotype, composed of dozens of matrices. The Los Angeles Times and other U.S. newspapers covered the story. Featured in the Times was a photograph of a page from Jyotipriya’s book, accompanied by the caption: “INTRICATE – PAGE OF 30,000 YEAR-OLD SANSKRIT LANGUAGE.” It was likely the first time the American public had ever had a glimpse of the language–or had even heard of it. The average American of the day might probably have thought, as someone actually said, “What is Sanskrit, some kind of war work?”

The Los Angeles Times quoted Jyotipriya’s enthusiasm for Sanskrit: “Not only are the languages used on the European and American continents deficient in words dealing with spirit, but many of the English words that do have spiritual connotations are so weighty with false and dogmatic beliefs that it is difficult to use them with any hopes of conveying an exact meaning to all… while Sanskrit, expresses the ‘inner mysteries of the soul and spirit, the many after-death states, the origin and destiny of worlds and men and human psychology.” The article ended with Jyotipriya’s assertion that Sanskrit is “as alive today as it was at the birth of thinking man on this planet.” Thus concluded Jyotipriya’s introductory lesson to the American people on the treasures of Sanskrit, the first of many in the course of her forty years as a pioneer and champion of the language. It is worth noting that Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion and Jyotipriya’s First Lessons in Sanskrit Grammar (a revised edition of Ballantyne’s 19th Century grammar which she prepared in collaboration with Dr Lawrence A. Ware) were the only books on Sanskrit to be found in 1940s America in the central research library of a city the size of Los Angeles!

1945 – The Point Loma experience came to a close, for reasons foreseen and unforeseen. Enrolment in the schools had begun to decline some years earlier… and the presence of an international community near the strategic San Diego naval base outside of Point Loma caused suspicion during wartime. Jyotipriya and other Point Loma-ites moved north to Los Angeles to continue their work. There, Jyotipriya taught for a brief period at the prestigious University of Southern California. A character reference of the time lauded Jyotipriya with these words: “I have known Judith Tyberg since her birth. I have observed in her the growth, ever clearly brought forth in action, of an unselfish and noble character. Combined with this she is an unusual and brilliant teacher.” And from another: “Miss Tyberg’s lectures were distinguished by wide reading and research; and even more than this, she imparted to her students and hearers the spiritual aroma and inspiration of the great philosophical schools of the East.”

Jyotipriya then began what was called by friends “a daring adventure”, and opened a Sanskrit Centre and bookshop where she taught Indian philosophy, religion, languages and culture. Through this she developed a large network of associations with other Orientalists and a unique, esteemed reputation. She lectured at colleges, churches, and clubs and on a more intimate level, continued two study circles that had become an integral part of her life since long before – a “Lotus Circle” that taught children about the lives of great people of the different nations through story and song, and for adults a Saturday evening “Get-Together” where people brought their sewing or knitting or whatever they had to work on, while Jyoti presented the teachings of the great sages of all time. She continued her own individual studies in comparative religion and myth, in Hindu astrology and, though hampered by a poverty of research resources, plunged into an even more intense pursuit of the wisdom contained in Sanskrit scriptures.

V.K. Gokak once characterized Jyotipriya’s life as one of “a ceaseless search for Truth.” Her quest took a crucial turn at a 1946 lecture given by Dr S. Radhakrishnan, Vice-Chancellor of Benares Hindu University, sponsored by the University of Southern California. And as if to initiate the New Year, in January 1947 Jyotipriya addressed a letter to the President and Officers of Benares Hindu University:

“Dear Gentlemen:

I would like to enter the Oriental Department of your University for research work and help from your Sanskrit professors and pandits. I have decided to give my life to the spreading of the beautiful teachings and religious-philosophy as found in Sanskrit scriptures. One of my projects is to make a good English rendering of the complete Yoga Vasista for the West. Only portions of it have found their way here, and those bits kindle in me a sympathetic note and I would have the West illumined by its perfect philosophy…”

Then, in a letter to J.K. Birla inquiring about financial assistance she explained the situation in America:

Spiritual and Oriental work of the higher kind, especially along my line, do not bring in the big sums that material lines of work do here in America. In my little Sanskrit Centre here which is not too fortunately placed due to my small means, I have just covered my expenses for my simple way of living with the little income that comes from my classes and lectures and from the little I make on the sale of books. But I am so happy to have at least made a go (as they say here) of my little Sanskrit Centre. When one dares and goes ahead with an unselfish heart and is convinced the work is for the progress of humanity help does come. My pupils are devoted to me and have helped me out of awkward situations and the older ones with much worldly experience give me legal help free.”

J.K. Birla wrote to Jyotipriya in reply:

“It has given me great pleasure to learn how sincerely devoted you are to… Sanskrit learning. We are reminded of the learned Gargi of Ancient India, when we think of you, spreading the message of Arya (Hindu) Dharma and philosophy, with a missionary zeal among your countrymen. For this we offer you our sincerest appreciation and deepest gratitude. I assure you of all that I can do for your laudable ambition.”

The final letter in the series of correspondences was addressed to all the friends and associates of Jyotipriya’s Sanskrit Centre:

“I am happy to let you know that I have accepted a three-year scholarship for Sanskrit research at Benares Hindu University. I would like to thank each and all of you for the privilege of sharing our mutual experiences in the search for Truth and for all the help you have given me.”

Dr Judith Tyberg, soon to be named Jyotipriya, left for India in June 1947 as a Seth Jugal Kishore Birla Scholar and an honorary member of the Arya Dharma Sewa Sanghs, an association that “advanced the spiritual laws and self-directed evolution and ultimate liberation of the Soul.” At the age of 45, Jyotipriya would find the answers to her lifelong quest when a few months later she would find her way to Pondicherry.

“Our life is a horse, that, neighing and galloping, bearing us onward and upward… we seek for the shining gold of the Truth; we lust after a heavenly treasure.” Sri Aurobindo.

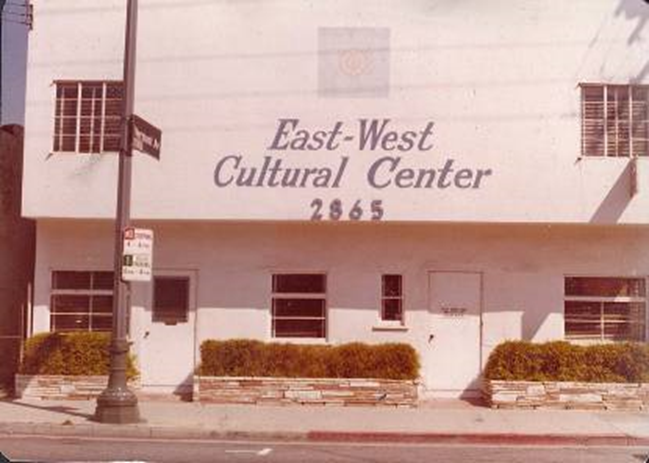

ONE of Jyotipriya’s favourite stories had to do with the time she met a yogi at the home of a friend of the American Consul, not long after her arrival in India in July 1947. When the others stepped out of the room for a moment, the yogi asked to see Jyotipriya’s palm, and surprised her by saying, “I see you were born on 16 May 1902.” Then, remarking on how rare it was to meet anyone with so much written in the aura as had Jyotipriya, he proceeded to make a number of predictions about her life. First, he said that all her training had been in preparation for a great future work – and that she would “teach and teach and teach.” And he told her he could see people streaming in and out of a large building she would have, a building surrounded by seven trees. “But how can that be?” she replied in astonishment, “I don’t have a penny to my name!” At this point, the Consul and his wife who had returned to the room joined in the conversation with the question – “Will she ever have any money of her own?” – for they were greatly impressed with how much Jyoti could do with the little she had. The yogi concentrated before giving his answer: “She will always have money for her spiritual work, but not for any other needs.” He then continued by forecasting some problems she would have with her health but concluded that they would never stop her – and that Jyotipriya’s life would just grow fuller and richer right up till the end.

All of the yogi’s predictions were fulfilled: the present home of the East-West Cultural Centre came landscaped with seven trees, and was a spiritual haven for the thousands it welcomed through its doors… there was money always and only for the Centre’s work… and, despite a series of extremely painful illnesses, Jyotipriya continued to teach until the final days of her life. Her last Thursday evening satsangs were said to be luminous, and plunged sadhaks and seekers even deeper within than ever. But back in 1947, that yogi had made one more disclosure – this one about Jyotipriya’s immediate past as well as her future. He stated that she had already found her guru and guide for life. And again, the yogi proved correct – for she had just returned from Pondicherry and her first darshan with Sri Aurobindo. Ostensibly, Jyotipriya came to India to work towards an M.A. degree in Indian Religion and Philosophy at Benares Hindu University (B.H.U.), on a three-year scholarship from the Arya Dharma Sewa Sangha. She arrived at the holy city at an auspicious time – one month before India’s Independence was achieved. But Jyoti had a deeper purpose than that of adding another academic degree to her already full roster of achievements. She had come to India on a spiritual search. After twenty-five years of intensive research into the world’s sacred scriptures – and seventeen years of Sanskrit study – Jyotipriya was convinced that there was an inner meaning to the Veda that no one could teach her in the West. For, as she explained at her first meeting with the University’s Philosophy Department, if all of India’s spiritual culture was indeed based on the Veda, then what she had learned in America could only be called “nonsense.” But the scholars of the time were in debate as to whether there was a secret to the Veda at all. No pandit yet had been able to decode the obscure language and unravel a consistent thread of spiritual sense. In the prevailing view, the Veda was but “an interesting remnant of barbarism.” Jyotipriya was advised to choose another Sanskrit research topic.

It happened that a young philosophy lecturer, by the name of Arabinda Basu, was in the Teachers Room at the time, and he followed the dismayed Dr Tyberg out into the hallway. “I couldn’t help but overhear your conversation,” she recalled him to say, “But I do think I know of someone who can help you. Have you ever heard of Sri Aurobindo?” The next day, he brought her a copy of Bases of Yoga – and a typescript of the not-yet published Secret of the Veda. Jyotipriya stayed awake reading until dawn, for, in her hands, she discovered, were the answers she had been so long seeking. That morning, she told Arabinda Basu she had found what she had come to India for.

Along with Arabinda Basu’s letter of introduction, Jyotipriya sent a letter to Sri Aurobindo describing her lifelong quest for Truth and requesting permission for His darshan. Then, after two days, a strange thing happened – Jyotipriya began to smell jasmine flowers everywhere she went, though there were none anywhere to be seen. And even more curious, the fragrance would grow more intense whenever Arabinda Basu would speak about Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. With her logic at a fail, Jyoti, at last, cycled over to ask Basu if there could be some possible explanation for such a curious phenomenon. His reply: “You’ve contacted Sri Aurobindo, haven’t you? Well, now he has contacted you. Soon you’ll be receiving a letter.” And in the correspondence that did soon follow, Jyotipriya was informed that she was welcome to visit the Ashram at any time.

Her first opportunity came with the Rama holidays of October 1947. She wrote in her diary, “This is considered one of the most propitious seasons of the year for spiritual conquests. Very auspicious me arriving just at this time I think.” And so it was – she reached the Sri Aurobindo Ashram on the evening of Lakshmi puja – just as the Mother was about to give blessings to all. At the touch of the Mother’s hands on Jyotipriya’s head, “electric forces” went right through her being; her hands were “sizzling.” Jyoti walked away wondering what had happened to her. In the days to come, she was to recognize in the Mother “a Goddess friend of old” and a very deep love for the Mother filled her heart. The affection was mutual. Purity was very dear to the Mother and, of all Jyotipriya’s qualities, it was her purity that was most outstanding. Indeed, it was appropriate that Sri Aurobindo used the fragrance of jasmine as His way of communicating with her in Benares – for jasmine, as the Mother has said, is the flower of purity. At Jyotipriya’s first private darshan with the Mother they talked for an hour, and among other things the Mother explained to her the significance of the flowers. Deeply moved, Jyotipriya expressed her longing to give her life to all that was Beauty and Truth. The Mother, silent for a moment in reflection, replied, “Yes, you chose long ago to serve.” Then She told Jyoti that She and Sri Aurobindo had been waiting for her to arrive for a very long time. It was then that the seeker still known as Judith Tyberg asked the Mother for a spiritual name. At the next morning’s pranam, the Mother handed her a chit written in Sri Aurobindo’s script. Inside were the words -“Jyotipriya, the lover of light.”

Darshan of 24 November 1947, at last arrived. Tall in stature, Jyotipriya could see over most people’s heads while waiting in the queue, so she had her first and sustained view of Sri Aurobindo long in advance of her own pranam. Standing before Sri Aurobindo, she felt she was being “stretched out to infinity” – “I just felt God, a marvellous feeling of expansion. I was out of myself, it was so beautiful, it was with me for days. He did something to me, because all down my spine there was this electric current and whirling movement.” And as she told one Los Angeles devotee, “He made me so aware of the soul within me. Even though I had all these aspirations which were in the soul, I became aware of something so different that was alive in me. I really knew what was my soul.” Henceforth, Jyotipriya always was to refer to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother as “Devaguru and Devamata” – or Divine Father and Divine Mother. For from that indeed propitious Rama holidays season on, Jyotipriya’s “soul-doors” were opened and “a new consciousness directed” her life ever after.

Back in Benares for her studies Jyoti brought that new consciousness to bear on everything she did. As the University student most advanced in years, she proved to be the most distinguished. She learned Hindi and Pali, and deepened her knowledge of Sanskrit through detailed studies of the Gita, the Upanishads and the Brahma Sutras. She studied the Vedantic systems of Philosophy, and modern Indian thought. And after the March 1949 examinations for the M.A. standard, Jyotipriya had this to write to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother:

“Yesterday my thoughts were very close to you both when I received the news that I had passed First Class in the M.A. examinations in Indian Religion and Philosophy and had made a record for the University. This I know was because of the divine channels of help I was able to open by my love of you and the path of life you offer…. The question: ‘State clearly and briefly the philosophical and religious views of Sri Aurobindo… ‘ – I answered fully and enjoyed pouring out my soul in it.”

At the age of 48, Jyotipriya took up the study of Indian Classical Music, learning sitar and sangit so she could “sing bhajans to the Divine.” As Hostess of the International Guest House planning activities for a weekly group of 40, and as the first President of the International Students’ Union, founded by Dr Radhakrishnan, Jyotipriya was “a real force in international understanding,” to use the then Vice-Chancellor’s own words. But her real satisfaction came from the hope that in those capacities she might be a “divine channel” and make the walls of those assemblies “ring with reverberations of eternal things.”

Many eminent people of the day were impressed with Jyotipriya’s Sanskrit scholarship and her sincere appreciation of Indian culture. It was her great privilege to meet with Gandhiji, Maulana Azad, Rajagopalacharya, Santoshkumar Basu, V.K. Gokak, and pandit Mahamahopadhyaya Gopinath Kaviraj. She served as India’s representative to the World University Round Table in the august company of Swami Sivananda, who was to become a revered friend for life. Perhaps Professor B.L. Atreya of Benares Hindu University spoke for them all when he praised Jyotipriya’s close study and admiration for the vast and profound aspects of Hinduism, and for living “like an Indian” in full participation in Varanasi life. But such an interest and enthusiasm was only natural for Jyotipriya, for she loved meeting all kinds of people. And, as a lifelong friend commented, – when inquiring in a letter to what degree Jyoti’s outward behaviour had become Indianized – the “insides” had been “always of that character.” Because of Jyotipriya’s knowledge of Hindi and Pali, she was able to visit many holy places ordinarily not accessible to visitors from the West. It was the then Education Minister Maulana Azad who “challenged” her to bring to the West her deep understanding of Indian culture, while B.H.U.’s Professor T.R.V. Murti predicted: “I am convinced that you are destined to play an important role in bringing the West and the East together on a spiritual plane.”

Jyotipriya lived to fulfil the prediction and the challenge. In the thirty years that passed from the time she had left India in 1950, until her death in 1980, she brought to seekers of all races and ages in the West her stories of spiritual experiences and contacts with the holy people of India. These anecdotes were her most enjoyable – and effective – way of opening hearts and minds to the existence of a spiritual reality. She delighted in telling of her many hours in the company of Ma Anandamayee, whom Jyotipriya with her own joyous nature liked very much and regarded as an “incarnation of happiness.” She would sit alongside as Anandamayee Ma would sing to the Divine in her Bhavan by the Ganges. And there were Jyoti’s descriptions of the ashrams of Rishikesh – of the Sivananda Ashram, and her time with Krishna Prem (Ronald Nixon) in particular. But two stories deserve special mention. One was from the time Jyotipriya first visited Sarnath during a Philosophers’ Congress held in Benares at Christmas. After touring this holy site where Buddha had first preached, the group entered the museum. And there, before one of the statues of the Buddha, Jyotipriya was held spellbound and could not move. The others went on, but she stood transfixed for a long time, alive with the Buddha and he with her. From that time of gripping memory, Jyotipriya was convinced that she had lived a past life in the blessed company of Siddhartha Buddha. Then, there was the week that she spent with Sri Ramana Maharshi – he, lying on his bench, Jyotipriya and many others gathered around. As for most, Jyotipriya found it very easy to meditate in the pure atmosphere of that sage. Her diary is filled with the record of her questions to him and his replies. But one exchange especially stood out. Jyotipriya asked Ramana Maharshi what she would do when all of her spiritual teachers would depart from this life. He assured her with these words – “We’ll never leave you. None of your teachers will ever leave you.” Then he added, “You’re already realized, you just don’t know it.” And in the library of the East-West Cultural Centre, to the side of a large and radiant portrait of Sri Aurobindo, is a smaller framed composite of Ramana Maharshi, Anandamayee Ma, and the other saints of India who helped lead Jyotipriya to her spiritual goal.

But as Jyoti wrote to the Mother in the summer of 1949: “In all my travels I am seeing all the many religions and devoted followers of Krishna, Rama… but none of these have had the wondrous effect that you and Sri Aurobindo have made on me. I have been able to prove this by first-hand experience.” After the Darshan of 15 August 1949, Jyoti was convinced that her place was with the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. She wrote in a letter to her friends: “At this darshan, I came to know without doubt that I belonged to Him and His work in the world.” But still, she felt bound to her many responsibilities in Benares, though her studies themselves were completed. In deep turmoil, she called on the Divine for a definitive answer. And there, in the railway station in Calcutta – and again with no possible logical source – the fragrance of jasmine came upon her, just as it had done two years earlier in Benares.

Those of us who have come to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram through Jyotipriya and her East-West Cultural Centre – and who have received such a warm and immediate welcome just by virtue of our association with her – have felt the living regard and affection which the Ashram held for Jyotipriya. She is remembered for discussing the wonders of Sanskrit on the ashram verandah till late into the night… for her deep study of Savitri at a time when it was read by few… for her practical and loving advice to a teenage ashramite… for her respect for Indian customs and for “everything Indian”. To quote one young ashramite’s letter to the Mother about Jyotipriya, a letter which Jyoti kept and cherished: “When I was introduced to Jyotipriya, I felt a kind of warmth deep within that provoked in me a feeling of confidence. Every time, in her nearness, this happy feeling persists. I like to see her, to listen to her; it does something to me.”

And for Jyotipriya, there just were not enough accolades to describe the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. It was her “spiritual home”… it was where she found the answer to her “deepest heart’s longings since childhood” it was “bustling with all the things” she loved… the spiritual atmosphere was “dazzling, harmonious”… the physical education program was “fine training, and so united in spirit”… and in the ashramites, and close friends like Nolini Kanta Gupta, A.B. Purani, Indra Sen, Sisir Mitra, and Prithvi Singh, Jyotipriya saw “the cream of Hindu culture”. She treasured the honour of spending so many morning hours in questions and dialogues with the great Sanskrit pandit, Kapali Sastri – and always thrilled to the memory of the words “Bilkul theek” – “Perfect” – he pronounced when she first chanted the gayatri for him after just a few days of practice. Proudly, she would point out to us in Los Angeles the album photograph of her white-shorted participation in March Past. And her heart would fill with joy to recall the Mother’s pleasure at a concert given for Her at Golconde by Jyotipriya’s three music students, or at the Christmas carols sung to Jyoti’s organ accompaniment for the Mother in the playground.

In whatever Jyotipriya did, she brought others along with her. If there was music to be practiced, she infused in the student her own joy and love in the learning. It was through her many contacts that the Ashram came to know of Johannes Hohienberg’s 1915 portrait painting of Sri Aurobindo. Jyotipriya’s annual Christmas letter from India, of 22 single-spaced typed pages to over 400 friends, once caused someone at the Ashram to suggest that her time would be better spent in the pursuit of her own sadhana. In a quandary, Jyoti went to ask the Mother for Her advice. Throwing up Her hands, the Mother said: “How do you think the Divine works if he doesn’t work through people like you? You keep up all your contacts!” So Jyotipriya queried, “But if I keep to my own sadhana, I’ll go along faster?” To which the Mother replied, “Yes. It is that way. Just work on your own sadhana and you go very high, but you leave everybody else behind. The way you grow, you take others along with you. It is slower, but it is a much more rich and beautiful and cosmic path.” And then She repeated what She had told Jyotipriya at their first meeting years ago, “You have chosen it – to serve – long ago.”

Jyotipriya went back to America to serve in March 1950, after a last darshan of 21 February. She recorded her final impressions of Sri Aurobindo: “Vast deep calm dynamic with a mighty wisdom…Had time to really have a good look. He looks so well and strong and fair, yet His consciousness seemed infinite, not just local. Such currents!” She felt that the message given to her then was this: “Have trust therefore in us, absolute trust, and we will lead you to your goal.” As a fitting close to the three-year stay in India that was the treasure of Jyotipriya’s life, Arabinda Basu, who had led her to Sri Aurobindo, saw her off at the boat at Calcutta. Then, as she wrote in her diary, “With thoughts of Ma and Guru” she departed. Armed with the future, Jyotipriya went back to the West to become Sri Aurobindo’s and the Mother’s premier pioneer in America.

“For you who have realised your soul and seek the integral yoga, to help the others is the best way of helping yourself. Indeed, if you are sincere you will soon discover that each of their failures is a sure sign of a corresponding deficiency in yourself, the proof that something in you is not perfect enough to be all powerful.”

The Mother, December 1955

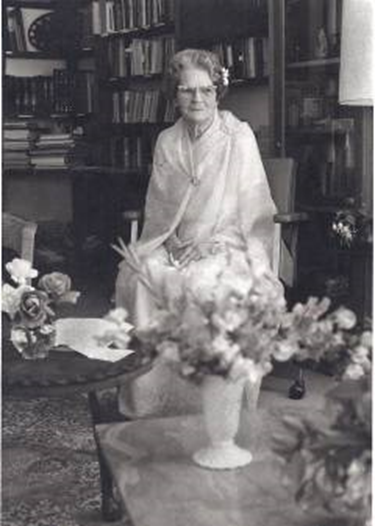

THE East-West Cultural Centre was located in a part of Los Angeles where the blare of radio rock music and the smell of barbecued beef filled the concrete streets. But when you entered the Centre founded by Jyotipriya, you stepped into another world altogether. Greeting you at the doorway were happy flowers, and a smiling picture of the Mother, garlanded by Her words, “Serve the Truth.” Up the stairs, in the library, were more flowers, perfumed wafts of incense, and a large, luminous portrait of Sri Aurobindo. The rooms were filled with the sounds of Sanskrit and mantras, spiritual literature, photographs of Tagore and the great saints of India. And then there was always the radiance of Jyotipriya, who would welcome you in with her beautiful smile and an outstretched hand. Thirty years’ worth of spiritual seekers each have that image of Jyotipriya engraved indelibly upon their souls.

True to her modest nature, Jyotipriya kept that treasured 1955 message from the Mother framed in a quiet corner of her study. Never one to boast or claim personal credit, she regarded the Mother’s words not as praise, but as challenge. In her view, there was never enough she could do to help manifest the Hour of God, and Sri Aurobindo’s great vision of a Supramental Divine Life on Earth. She was too self-effacing to say how it was through her labour of love that so many in the West came to know and cherish India’s spiritual light. Nor would she speak of how that endeavour was an uphill struggle every step of the way. If you were to ask her about the later years of her life, she would shift the talk to that child of her devotion – the East-West Cultural Centre – and of the many illumined souls who helped it to prosper and grow. In the history of the East-West Cultural Centre are the seeds of America’s present spiritual flowering-and the record of the last thirty years of Jyotipriya’s life.

Sri Aurobindo had envisioned for the United States an important role in the world’s spiritual awakening, and the Mother had once remarked how the American people were capable of enthusiasm and aspiration and plunging into the future.” When Jyotipriya first arrived back in America in April 1950, the truth of the Mother’s words appeared to be immediately borne out. Jyoti’s three years in India had not weakened her network of contacts and, within 48 hours of her reaching the California shores, calls for meetings and lectures began to pour in. During the voyage back from India, Jyoti’s ship had docked in Hawaii, giving her the chance to meet and discuss with her old Benares friend, Professor Charles Moore of the University of Hawaii, the results of his 1949 East-West Convention of Philosophers which had been attended by many eminent personalities, including the Zen Buddhist, Suzuki. From their talks, Jyotipriya gathered ideas for an approach to Sri Aurobindo that might readily appeal to the Western mind. But once back in America, she had little time to prepare in advance for her talks. Her schedule was “packed”, and as she wrote to Sri Aurobindo Ashram Secretary Nolini Kanta Gupta: “Am trying to plan some kind of schedule, but evidently something or somebody else is also planning just a little bit ahead of me, so I just take the calls for lectures as they come in… It seems I am destined to do public work for the Divine.” In her first week, Jyotipriya addressed enthusiastic audiences numbering 80, who kept her busy for two solid hours after the lectures answering questions at the door. In the following week, she gave nine speeches, and then addressed a church congregation of 1,000! The result of another occasion was a letter of reverential greetings sent to “Rishi Sri Aurobindo,” signed by over 90 American seekers. The United States was eager for “the uncensored truth about India,” and Los Angeles – Jyotipriya’s home base – was, in her words, “just teeming with interest in Sri Aurobindo.” Jyoti then was asked to keep a similar crammed schedule in San Francisco, where she reported an enthusiastic reception at prestigious Stanford University. From that time on, she divided her energies between the two cities, five hundred miles apart.

But whether or not Jyotipriya had time to prepare for any of these talks did not seem to matter, for once before an audience she felt “driven by another force” – a power that gave her “a greater ease in speaking” than she knew to be usually her share. This force that would come down in great “swirls” from above her head, would set her “upper body vibrating” and get her “centralized to speak.” It was then that she would feel the Ashram atmosphere surround her, and feel in a concrete way the living presence of the Mother. After nearly every lecture she was booked for another engagement.

In 1951, Jyotipriya accepted an appointment as Professor of Indian Religion and Philosophy at the newly-founded American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco – the same institution where Frederic Spiegelberg and Haridas Chaudhari were positioned, and Dilip Kumar Roy was later to teach. An eternal student herself, Jyotipriya quickly established a rapport and confidence with her students. Mature graduates were to repeatedly tell Director of Studies Spiegelberg of her “superior teaching abilities and about the way she understood to make every single class meeting a vitally interesting one.” At a 1952 Summer International Relations Workshop on India at San Francisco State College, her educational leadership was praised as “exceptionally effective.” In these professional activities – and in her private at-home meetings for “friends of the spirit” – Jyotipriya was busy “casting Sri Aurobindo’s pearls” about on every opportunity and occasion. For, as she wrote to the Mother, “You must know how happy I am to have something so genuine to offer those seeking truth… I just must share my great happiness and blessing with others.”

This open and enthusiastic mood in America ended abruptly with the outbreak of the Korean War. Once again, the death-toll of American boys fighting in foreign lands was mounting day by day, and the nation’s former interest in global neighbours froze into a hard isolationist stance. India’s foreign policy grew suspect, and. the frenzy of fear of an all-out holocaust made materialism America’s saviour of the day. In a letter to Nolini, Jyotipriya described how “the selfishness and fright were escalating, the hoarding and amassing of wealth and possessions reaching an unbelievable pitch.” It was in this atmosphere of suspicion – where “those interested in spiritual things are very much in the minority” – that the East-West Cultural Centre was born. The fledgling American Academy of Asian Studies began to walk a tight-rope of finances and diplomacy. To use Jyotipriya’s tactful description, “lack of funds to pay for teaching made it necessary” to seek elsewhere for her to serve. And in what seemed at first to be a disastrous and incomprehensible turn of events, was the impetus for Jyotipriya to found a religious institution where she could teach Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s Yoga without restrictions.

The East-West Cultural Centre was inaugurated on I May 1953 – the month of Jyotipriya’s 51st birthday – in a small room in the home of a friend in Los Angeles. In keeping with the times, the objectives stated in its first brochure announcement were “broad and non-sectarian – East meets West in cultural reciprocity for greater world unity… in the fields of the living arts and philosophy.” The Centre offered language classes in Hindustani, Sanskrit, Pali, and Greek; courses in the art, culture, history, and religions of India; studies in Comparative Religion, the Sacred Scriptures and great sages of all time; study groups in Savitri and The Life Divine, and the Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. There were opportunities for guided individual research, and Jyotipriya’s “Oriental Library” was opened to the public. Books on India’s many yogic paths were available for sale. The East-West Cultural Centre School for creatively gifted children in grades 2-12 was also initiated in 1953. Promising “high ideals, aesthetic and studious habits formed,” the school conducted classes in New Math, phonics, history, geography, science, art, music, piano, and typing. All of the East-West Cultural Centre activities – for both adults and children – were organized and taught by Jyotipriya single-handedly. Alone, and without any financial support save the modest fees that were the payment for her teaching, she carried the venture forth.

Something of what Jyotipriya was up against can be glimpsed from two of her letters, written a decade later, to Ashram friend Prithvi Singh. Only in 1960 could she write: “The feeling towards things Indian is certainly improving. The prejudice is fading away so I can be more open and frank about what I really am about.” But still, in 1962, she was to say: “We heard from Purani today from New York…. This lone kind of lecturing around the States is not an easy task in material-minded America. You have to have selected audiences pre-arranged to have any real response.” But if ever there were personalities to woo into warmth the icy scepticism of an American audience, they belonged on the one hand to the ever-dynamic A.B. Purani – and on the other to Jyotipriya. Few people had her “wide spiritual horizons”… those reminiscences “spiced with rare humour” and “the best thinking of both East and West”… her “sympathetic rather than critical” outlook…and that “dedication prompted by a “love of mankind” – to quote from a very apt description circulated by a group called The New Age Questors, which would often sponsor Jyoti’s “My Search for Universality” talks. Jyotipriya had the gift of drawing people to her, and a real skill for creating attendance worthy activities and media-catching events. Premium newspaper coverage came with her “Open-House” lectures explaining Indian Art, which she coordinated in a very timely way with a national magazine’s spread on the subject. Expensive radio publicity for the Centre was gained without cost when a local station queried Jyotipriya about a tour, called “India and the World,” which she was asked to lead for a non-profit Study Abroad group.

And the Centre grew. From one small room…to all the rooms of her friend’s house…to a large rented hall just the next year… and on Thanksgiving Day 1955 – which that year coincided with 24 November, Sri Aurobindo’s Siddhi Day – to a home of its own, when devoted students unexpectedly presented Jyotipriya with 15,000 dollars to pay for the down payment and first mortgage on the purchase of a building and property. She accepted their generosity on the sole condition that it was to be a loan which through her earnings she would repay. The first celebration of Sri Aurobindo’s birthday in this new home took place in the Centre’s 125-person capacity auditorium. Twenty young people participated in presenting through drama, recitation, and dance, a sweeping panoramic view of India’s wealth of spiritual tradition. The climax of the program came with a powerful portrayal from Sri Aurobindo’s epic, Savitri – the dramatic confrontation between Savitri, Daughter of the Sun, and Yama, Lord of Death. Jyotipriya wrote to the Mother how she felt “a wonderful presence” as the two youthful protagonists gave their speeches by heart. The afternoon ended with the singing of Bande Mataram – India’s spiritual anthem – and the recitation of one of the Mother’s prayers.

The East-West Cultural Centre School too flourished, soon receiving all city, state, and national government certifications. Jyotipriya’s “special tricks for making things easier,” her devotion, and the focus on the children’s “god-like qualities” resulted in their acceptance by leading colleges as much as two years in advance of public school pupils. Jyotipriya’s students – from generations spanning 1953-1973 – were to recall their years at the East-West Cultural Centre School as “a wonderful and unique opportunity.”

The “Cold War Fifties” gave way to the “New Age Sixties.” Across America, interest in Yoga was abroad. Jyotipriya was there and ready to nourish the very first shoots, as the Mother’s prediction about America’s spiritual flowering began its burst into life. The East-West Cultural Centre quickly became known as a headquarters for information on India to which inquiries came in on a non-stop basis. It was one of the only places in the United States where one could purchase a complete line of literature on the many limbs of yoga, no less than learn Sanskrit – and to help the influx of new students, Jyotipriya added for sale her own cassette recordings of Sanskrit vocabulary and mantras. The Centre’s mailing list expanded; its reputation grew. There were a whole range of activities, all emphasizing spiritual themes.

The public was invited to attend Indian luncheons, dinners, and teas…movies of Eastern lands…dramatic readings from Indian literary classics… evenings of Indian Dance. Many were the times an audience would drift into enchantment with the weaving of a raga on sarod, or the walls resound with the aspiration of a harmonium bhajan rising straight upward to the Divine. With her melodious voice, Jyotipriya would hold centre-stage to chant in devotion the slokas – learned at the feet of the pandit Kapali Sastri, during her treasured Sri Aurobindo Ashram days. From all these activities, a spiritual community began to be built up.

Soon, serious young seekers, who were “reverently in tune” with the teachings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, came to work and live at the Centre, to share in the inner life of its spiritual heart – the Jyoti Ashram, for “leaders and lovers of light who radiate Truth.” The dynamic personality of Swami Chidananda – who gave “a beautiful tribute” to the Mother at the Centre’s celebration of Her 82nd “Bonne Fete” – attracted more seekers to the East-West Cultural Centre. Revered friends and eminent personages from India, such as Swami Ramdas and Mother Krishnabai, His Holiness Jagadguru Sankaracharya of Puri, V.K. Gokak, and Indira Devi brought their light to shine. Jyotipriya’s auditorium on Sunday afternoons became known as a starting-off place for holy people from the East in the United States. Indian gurus, in turn, would often send their American disciples to visit Jyotipriya “and be benefited.” The Swamis Muktananda, Satchidananda, and Vishnudevananda – who have helped guide many young Americans to the spiritual light – all were early East-West Cultural Centre guests. Anandamayee Ma wrote how “very pleased” she was to hear about Jyotipriya’s activities. Jyoti received this message from Rishikesh:

Adorable Self, … I greatly admire the solid work you do for the spiritual good of mankind in a silent manner. This is dynamic Yoga. The whole of America will be grateful to you. With regards, Prem, and OM, Thy Own Self, Swami Sivananda.

But if anyone were to try to credit Jyotipriya with the Centre’s growth and progress, she herself would be the very first to transfer the praise to “the Mother’s spiritual help and power” as the force that kept everything moving ahead despite the many obstacles that continually arose. She wrote to Prithvi Singh: “I know Her help is here all the time because of the many unusual things and blessings that happen all the time.” In the category of both “unusual” and “blessing,” was the situation that came about after a major Los Angeles earthquake, when Jyotipriya was wondering to herself how in the world she would be able to pay for the damages to the Centre caused by the tremor. The next morning, a repairman showed up, saying he had come to work on the building. Denying any payment for his services, he left as suddenly as he came – when the costly reconstruction work was complete. Then, there was the story of how the East-West Cultural Centre came to move into its present home – the large building with seven trees that that yogi back in ‘947 had fore-visioned. The United States Government, continually revising its building standards for a centre of educational work, one day informed Jyotipriya that she had exactly 90 days to relocate all of the Centre’s activities into a larger property with a parking lot – or be closed down! It took one year and a half of real estate searches and court pleadings until the Centre at last was located in suitable new quarters. And Jyotipriya, who faced a judge three times, with the Mother’s Blessing Flowers in hand, knew in her heart precisely who had saved her endeavour from total collapse.

These were the years when, despite all steps forward, the line from Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri “A vast surrender was his only strength” – became Jyotipriya’s familiar refrain. In 1960, when the United States Government at last accorded the East-West Cultural Centre a tax-free non-profit status as an educational institution, Jyotipriya wrote to Prithvi Singh: “I feel the time is not too far away when I will see Mother face to face again. After the worst debts are paid on the Centre and the taxes adjusted, things will be much easier, but at present we have to work pretty hard to keep all the bills paid.” As she wrote to the Mother: “It is hard for most people in India to understand the costs involved in living here in America. The standards for a Centre of Educational Work are very high and exacting. We must have the latest improvements in gas, electric fixtures, etc., etc., or we lose our licenses to carry on.” Jyotipriya had to wait until 1967 for that precious physical Darshan to take place. And it was not until I977 – when she was 77 years old – that she was to complete her payments on all the Centre’s debts. In all those difficult years of budget balancing and frugal living, no visitor to the Centre was ever pressed into making a contribution, and Jyotipriya continually sent, in her letters to the Mother, offerings for Her work.

The difficulties during the Centre’s growth were more than financial. Never married, Jyotipriya, as “a woman alone” in America, was often in a precarious situation, since her work was that of gathering people to her. Then, her small income always kept the Centre in modest-income neighbourhoods. Derelicts from surrounding areas would frequently wander into the Centre, mistaking it in their stupor for a Salvation Army Mission, and expecting from Jyotipriya “square meals” and lodging for the night! Because she saw the good in everyone and the potential soul within, her quota for strange characters far exceeded any other person’s lifetime allotment. But no one was ever turned away. Once, a frequent visitor who had been suspected of repeated theft was caught “red-handed.” The person was duly asked “Please don’t steal.” But that is not to say that Jyotipriya did not have a strong streak of Kali in her nature. If a person proved insincere, as certain professed holy people turned out to be, Jyotipriya would immediately cut off all aid and connections. For she had a sharp impatience with falsehood – and particularly when it meant a misrepresentation of India’s spiritual light. Still, the upright person that she was, she would never speak against anyone, even if the result was to her own detriment. When asked about a cut in connections, she would simply say: “I cannot disclose my reasons, but I assure you they are genuine.” And the only thing that could dampen her spirits was not the number of times she was cheated, but the number of people who preferred what she called “spiritualistic phenomena of a rather low order” to the true spiritual light. Let it be briefly stated that Jyotipriya had quite a challenge before her to educate Americans in the difference between fascinating but often fraudulent “psychic phenomena”, and the true “psychic”, to use Sri Aurobindo’s terms – the soul consciously evolving and turning Godward to a life divine.

“Dr Tyberg is at home in the library sharing the wisdom and Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’ – is how the familiar heading for the Thursday night satsangs would read on the East-West Cultural Centre bulletin of events, sent to hundreds of subscribers each month. Intending the Centre to “open up the way for a vast truth,” Jyotipriya found the best manner of doing so was to let it act as a forum for the different aspects of the spiritual life. But she would not rest unless every seeker with whom she came into contact knew of “the highest path offered” – Sri Aurobindo’s “broad and integral” Purna Yoga. Thus, for her as for so many seekers of all ages, races, and occupations who gathered around her, the Thursday night satsangs were the high point of the week, since it was then that she could share in a depth not possible on other occasions the teachings of her Devaguru and Devamata. There, in the Library, before Sri Aurobindo’s portrait she would sit — the books for that night on all sides around her – ready to read with golden glow Sri Aurobindo’s vision of a glorious future for humanity, or the Mother’s expert instructions for voyaging to Tomorrow. Though there was a warmth and camaraderie among the group that would fill and often overflow the Library at those times, what drew people was not the prospect of a social evening but Jyotipriya’s ability to communicate Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s teachings, for – as one sadhika observed – Jyoti “did not interpret or ever become vague, or indulge in cliches, but seemed able to identify so completely with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother that one continually felt their presence.” Jyotipriya always said she liked it best when there were plenty of questions and lively discussion in the group, but oftentimes all present would just be quietly reflective, lost in her recollections of darshans with Sri Aurobindo and intimate moments with the Mother. Then would Jyotipriya read from her heart the revelation of Savitri, with an inspiration that profoundly prepared for the meditation to follow. One long-time sadhak, who started with Jyotipriya in the early days, when he was often the only other person in the room, recalled how during meditations he would open his eyes a little to look at Jyotipriya, seeing her “as through a veil,” watching as “she would turn into the Mother, Sri Aurobindo and the other great souls she knew”…. how friends from the Ashram who came to the Library on occasion would say that “that was the only place they had felt so strong a power outside the Ashram”… and how during the meditations, “the force was so powerful,” his body would bend. To end the evening, Jyotipriya would lead the group in a Sanskrit singing of Sri Aurobindo’s “OM Anandamayi” mantra, invoking the Divine. Bliss, Consciousness, and Truth were very tangible things in the still moments following the hush of that collective voice . Certain it is that anyone who stayed long enough in the company of Jyotipriya developed a deep and sincere love for Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, growing in all those weeks marked by Thursdays in an “inner attunement” with Jyotipriya, and that “silent comradeship understood by devotees in this collective yoga.” Today, graduates of Jyotipriya’s school of devotion can be found living as devotees and sadhaks all through the West, in Auroville, and at the Ashram. For countless seekers, through the history of the East-West Cultural Centre, Jyotipriya was a “golden bridge.”

Jyotipriya once wrote to the Mother: “It feels so strange to have these ills of body and yet feel so well and energetic and enthusiastic in my work for you.” The Mother once had told Jyotipriya: “You were in such a rush to come down and join in the work, that you were careless about the body you chose!” Despite the pain that afflicted her body throughout her adult life, Jyotipriya kept “cheerfully going on” right up till the end – conducting satsangs, accepting new professorships (The College of Oriental Studies, 1973; the Goddard College Graduate Field Faculty, 1975), and initiating students into Sanskrit’s “wisdom-treasury” until the final days of her life. For, indeed, it was in the joy of teaching that she would transcend all pain. The Language of the Gods, published in 1970, was the culmination of her earlier publications on Sanskrit and her 45 years of Sanskrit teaching. With introductory remarks written by both B.L. Atreya and V.K. Gokak, it was dedicated by Jyotipriya“ In reverent memory of Sri Aurobindo” – and was hailed as a “bold”, “original” and “pioneer work.” In 1972, Jyotipriya paid her last visit to her “spiritual home” to celebrate Sri Aurobindo’s Birth Centenary at the Ashram, and have the grace of a final physical darshan with the Mother. In 1980, after a miraculous physical recovery, she wrote to a friend at the Ashram her joy in the new lease on life that allowed her to conduct yet another beloved Easter Flower Festival, presenting the Mother’s spiritual meaning of flowers. She wrote: “I am going to be able to carry on as I have for 27 years.”

There is one image of Jyotipriya that will long remain in the memories of all those who were present at the Mother’s birthday celebration held at the East-West Cultural Centre, a few years back, when a group of sadhaks and devotees were asked by Jyotipriya to recite a selection of the Mother’s prayers. One by one, each spoke from the heart, prayers which Jyotipriya had suggested with an incredibly accurate insight into what was deeply appropriate for each seeker at that time. Then came Jyotipriya’s turn. With a radiant face, she began the words of the Mother’s meditation of 31 March 1917 – “Each time that a heart leaps at the touch of Thy divine breath, a little more beauty seems to be born upon the Earth…” In a moment, the atmosphere was one of a shrine. And smiling, Jyotipriya spoke from her soul:

“Thou hast heaped Thy favours upon me, Thou hast unveiled to me many secrets, Thou hast made me taste many unexpected and unhoped-for joys…”

Perhaps what illumined her whole being with so extraordinary a light, was her recollection of some experiences she had in 1956 at about the same time of year. In a letter of 8 March 1956, Jyotipriya took a tone that differed markedly from that expressed in her previous mid-February correspondence and wrote to the Mother: “It is hard to explain to you a new type of experience I’ve been having but I can only say it is a kind of sudden awareness at times of the presence of another realm with a different vibration and sound around me. It lasts only a few minutes at a time, but comes rather often at various times during the day.” The Mother’s message of the Supramental Manifestation reached Jyotipriya two months later, thus fulfilling the faith she always kept that all was “being moulded for something wonderful.” Then she, who was not only the Mother’s “petite enfant” but also Her friend, sent this cable on 4 May:

MOTHER REJOICE GLORIOUS SUPRAMENTAL BIRTH

GRATITUDE SURRENDER LOVING PRANAMS JYOTIPRIYA

But there was more gold to be manifested by Jyotipriya, as she continued to recite on that Mother’s Birthday Celebration day, for every line seemed to hold for her more meaning than even the one before, and in the rapt silence of that room she went on:

“…but no grace of Thine can be equal to this Thou grantest to me when a heart leaps at the touch of Thy divine breath… Tell me, wilt Thou grant me the marvellous power to give birth to this dawn in expectant hearts, to awaken the consciousness of men to Thy sublime presence, and in this bare and sorrowful world awaken a little of Thy true paradise? What happiness, what riches, what terrestrial powers can equal this wonderful gift?”

No longer aware of even the seekers who through her efforts were gathered there that day, Jyotipriya concluded the Mother’s prayer, with upswept hands, and a heaven-bound face.

Jyotipriya left her body at 3:15 pm on the third of October 1980. In her last testament she had written: “In the event of my death, I would like my body to be cremated and the ashes there from thrown among the flowers of a happy garden. May any service that may be held be one of meditation, music and prayer for the speedy return of my soul to the Divine for new joy, power and wisdom, so I may return again to serve the Light.”

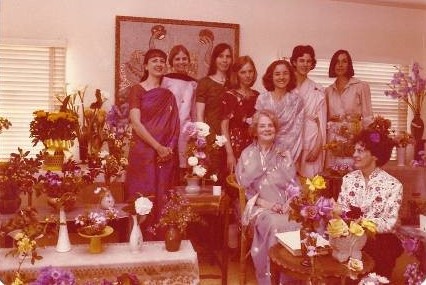

American yogini Judith Tyberg visits Sathya Sai Baba in 1967.

Judith, along with Charles and Faith Penn they edited a biography, covering the years 1968 to 1971, of Sathya Sai Baba called Sathyam Sivam Sundaram Part III by N. Kasturi.

From Sathyam Sivam Sundaram – Part II by N. Kasturi

Baba reached Prasanthi Nilayam from Brindavan, Whitefield, on the third day of July; the Murphets accompanied Him thither, drawn by the Love that He showered on them. Howard Murphet spoke on Baba at the Prasanthi Nilayam on the 21st and on the 23rd. Dr Judith (Jyothi- priya) Tybarg of the East-West Cultural Center, Los Angeles addressed the residents; she had a long talk with Baba, during which she asked Baba, whether movie films of His miracles can be taken and shown, to convince people of their authenticity. Baba replied that doubts would still persist. It is only by strengthening one’s own faith, by clearing the doubts in one’s own mind, that one can convince others. “Faith travels from one mind to another.” Baba then created some sweets for the group, demonstrating that He had nothing in His hand or up His sleeve. They came, through His “Sankalpa, Resolve.” They were not in the hand, but, “in the head,” He said. He revealed Himself thus to Dr. Judith, for, she was an earnest Sadhaka, soaked in devotion and scholarship. Her arthritis had been miraculously mitigated by Baba, who sent a few packets of Vibhuthi for her use through a person who returned to the U.S.A. from His Presence. He told her, “I am in all hearts. I am one with all. But, yet I never share their pain or their joy. I never experience sorrow or anger. I am Anandaswarupa (embodiment of bliss) and Premaswarupa (embodiment of Love).” No wonder that Maharshi Mahesh Yogi, the chief proponent of transcendental meditation, the holy man who has cast a powerful spell over the youth of the West, (“We who are tired of dead and decayed Western Culture will follow His Holiness, our Master, to the grave,” say, the hippies to him) wanted that Baba should bless the leaders of the youth of the world who are training themselves at Sankaracharya Nagar, Hrishikesh, to become the guides of Youth!

From Sathyam Sivam Sundaram – Part III by N. Kasturi

Dr Judith M. Tyberg of the East West Cultural Centre, Los Angeles, writes, “It is now almost three years that I was in Puttaparthi, and had the Divine Blessings of Sri Sathya Sai Baba. His help to me on all planes of being is still evident, and I am very grateful.”

Judith Tyberg (1902–1980) was an American yogi (“Jyotipriya”) and a renowned Sanskrit scholar and orientalist. Author of The Language of the Gods and two other reputed texts on Sanskrit, she was the founder and guiding spirit of the East-West Cultural Centre in Los Angeles, California, a major pioneering door through which now-celebrated Indian yogis and spiritual teachers of many Eastern and mystical traditions were first introduced to America and the West.

Many eminent Indians, political leaders and yoga masters alike, were impressed with Tyberg’s scholarship and her feeling for Indian culture: Mahatma Gandhi, Maulana Azad, V. K. Gokak, B. L. Atreya, Anandamayi Ma, Ramana Maharshi, Sri Ramdas, and Krishna Prem, and at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram: Kapali Shastri, Indra Sen, Sisir Mitra, Prithvi Singh, and former freedom fighters-turned-yogis Nolini Kanta Gupta and A.B. Purani, friends she referred to as “the cream of Hindu culture.” Tyberg spent a week with the sage Ramana Maharshi at his Arunachala ashram where he told her “You’re already realized, you just don’t know it.” Another lifelong friend was Swami Sivananda alongside whom Tyberg served as India’s representative to the 1948 World University Round Table. Tyberg was the first President of the International Students Union, founded by S. Radhakrishnan, who called her “a real force in international understanding.” Professor T.R.V. Murti declared “I am convinced that you are destined to play an important role in bringing the West and the East together on a spiritual plane.”

In Autumn 1949, Tyberg went back to Pondicherry for a six-month stay as a disciple at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. During her two years in India, Tyberg had kept up regular correspondence with an extensive network of American seekers. When certain people criticized this as unyogic, Tyberg asked The Mother for her view. Her reply was “How do you think the Divine works if he doesn’t work through people like you?” and she repeated what she’d told Tyberg at their very first meeting: “You have chosen it, to serve, long ago.” After a final reverence to Sri Aurobindo on February 21, 1950, Tyberg recorded her impressions: “Vast deep calm with a mighty wisdom … his consciousness seemed infinite … such currents!”