The following article is an excerpt from Enlightenment Magazine.

Though Sri Mataji Anandamayi Ma was not, strictly speaking, my guru, she certainly played a major role, to say the least, in my life and my sadhana [spiritual practice]. In fact, she still does today. Her memory is alive deep within my heart and there are several pictures of her on the walls of the ashram where I now teach. From my first physical encounter with her, in 1959, to the day in 1965 when she gave me her blessing to go to Sri Swami Prajnanpad (1891-1974), a relatively unknown master who was to become my guru—though I’d rather say of whom I gradually became the disciple—I considered Mataji as my guru. During those years, I repeatedly stayed with her for extended periods of time. Even after meeting Swami Prajnanpad, I always felt her active influence and kept visiting her, up to my last trip to India a few years before she left her body. To state things simply, I could say that, though in the course of my search and travels I have had the privilege to closely approach quite a few extraordinary beings—Tibetans, Sufis, Hindu gurus and Zen masters, many of whom left a deep imprint in my heart—to me Anandamayi Ma was and remains the embodiment of transcendence, the living proof of the actual existence of a transcendental reality. “Extraordinary,” “superhuman,” “divine”. . . I still feel today that no adjective is big enough to describe her presence, particularly when I met her, in the full blossoming of her radiance. I could barely believe that such a being could walk the earth in a human form, and I have no difficulty understanding how a whole theology was developed around her. I never, never met a sage whose divine appearance I admired so much. In truth, I admired her beyond all words. Thousands of pilgrims were of course similarly touched by her extraordinary presence, but I’d rather insist here on another aspect of Mataji: the relentless way in which she sometimes crucified the ego of those who wanted more than her occasional blessing. In fact, in her ashram, there was a very clear distinction between two kinds of visitors: those who came for her darshan [personal audience] and who received a warm welcome, and those who insisted on being considered her disciples, who were challenged and put on edge, to the limit of what they were able to bear—but never beyond. No guru wants to bring someone to absolute despair or to leaving the path because of unbearable trials. During the years when Denise Desjardins and myself were spending several months within the ashram as candidates to discipleship rather than as mere visitors, we went through a lot of that “special treatment.” Of course I realize, as I am about to recall a few examples of that treatment, that these stories may look very innocent, not so terrible to casual readers. The truth is, it is always easy to hear descriptions of someone else’s sadhana and to imagine: “Oh, had I been in this situation, I would not have been affected in such a way. I would have immediately taken it as a lesson, a challenge to my ego, etc. . . .” When you actually are tested, when your mind and ego are being provoked through situations which sometimes are in themselves very simple disappointments and difficulties, you are not hearing a story anymore. You’re in the fire, plunged into what constitutes the essence of all sadhanas: a persistent, sometimes harsh challenging of your ego and mind through situations which call into question your present identifications and attachments.

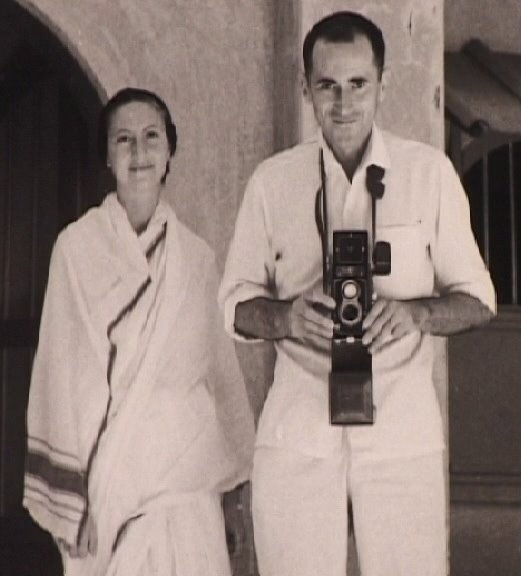

In those years, I was a professional filmmaker, working for French television. One of the things Mataji used to crucify my ego and teach me was the film I was shooting in her ashram. She sometimes granted me exceptional opportunities and then caused me to waste my last rolls, which I had very much been counting on. This was hard to accept. Following the advice of one of her ashramites, I had preciously saved three rolls of film until the very end of my stay. This had caused me to renounce shooting scenes which could have been important. Then, during those last days, every time I started filming, Anandamayi Ma, in front of everybody, either turned her head or winced. This was all the more cruel to me since I believed the person who had asked me to save those rolls had been inspired by Ma. Eventually, Ma only allowed me to shoot one roll. As this was after sunset, I was convinced there would be no visible image on the film. Incredible as it may seem, there was something: three of what may well be the most beautiful shots of the whole film, where Ma can be seen at night surrounded by a few disciples. These miraculous forty seconds were worth the sacrifice of those three rolls. Once she asked me to project the images which to me were most precious with some worn-out Indian equipment, when I knew for sure that it would irremediably damage the film.

I also remember a particular incident. I had always dreamed of meeting what I then called true yogis—not yoga teachers, but yogis having attained mastery over certain energies or developed certain powers. To me, those yogis embodied the whole legend of India. They lived in the high valley of the Ganges where I had not yet been able to go, since the Indian government had not granted me the special permit then necessary to travel to that region. One of those famous yogis was about to come down to the plains to visit Anandamayi Ma. On this very day, Ma asked me if I could travel with my Land Rover to a distance of some 150 kilometres where I was to pick up some luggage and bring it back. The roads were not tarred, it was raining, there was mud all over, so that when I left the ashram, the yogi had not arrived, and when I came back, he had already left. To me, at the time, this was a terrible disappointment indeed, a broken dream.

Every time my ego desperately wanted to be acknowledged by Ma, circumstances were such that I could not see her privately for weeks. But once, when, after having gone through what one usually calls intense pain, I at last changed my inner attitude, she herself took me for a ride in the car. I was alone with her, the driver, and a great pundit whom I very much admired. She had me sit next to her and did not allow anyone else to go with us.

We often had the impression that others were also brought to teach us and that the whole world was consciously or unconsciously serving Mother’s purpose. She was an incredible source of energy, the centre of a huge activity.

It is difficult to imagine what surrender to Anandamayi Ma, as some of her closest disciples were living it, could mean. I remember one monk whose ideal of life was to meditate. He had been meditating in an isolated ashram in the Himalayas and was very happy, until Ma appointed him as the swami in charge of the Delhi ashram.

Every day, he had to deal with curious visitors, Europeans, people from the embassies and consulates. He was forced to be no longer a meditator but an administrator, immersed head to toe in active life—the exact opposite of what he had been aspiring to. He was working twenty hours a day and I even once saw him slowly fall down. He had simply fallen asleep while walking. Just contemplating Anandamayi’s radiant smile, one could not imagine the pressure she put on some—in the name of ultimate freedom.

To conclude, I’d like to say that, remembering Ma as well as my guru, Swami Prajnanpad, I feel especially grateful for the occasions when they caused me pain, when they brought suffering to my ego. They, of course, never did me any harm. On the contrary, everything they did, whether they smiled or were angry at me, served my ultimate good. But they certainly made me feel severely hurt at times.

And the truth is, one cannot make any progress in one’s sadhana if one’s ego and mind are not sometimes painfully shaken.

Arnaud Desjardins is the author of many books, including two which have been translated into English: Toward the Fullness of Life (Threshold Books) and The Jump Into Life: Moving Beyond Fear (Hohm Press). He resides and teaches at his ashram, Hauteville, in the south of France. (died in 2011).

Source: Enlightenment Magazine.