A boarding and day-school for boys and girls, the Rajghat School taught from kindergarten to high school and college levels. Rajghat was one of the two schools of the Rishi Valley Trust, founded by Annie Besant and handed over to Krishnamurti so he could implement his ideas. It was an experimental community where students and teachers lived together following his philosophy.

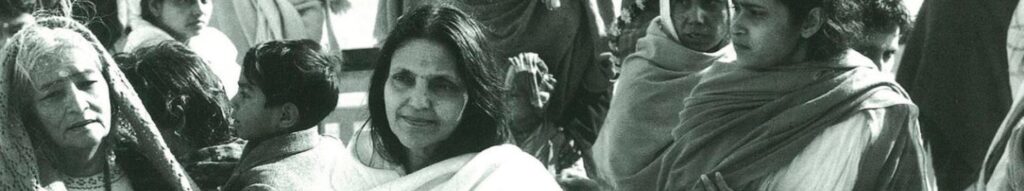

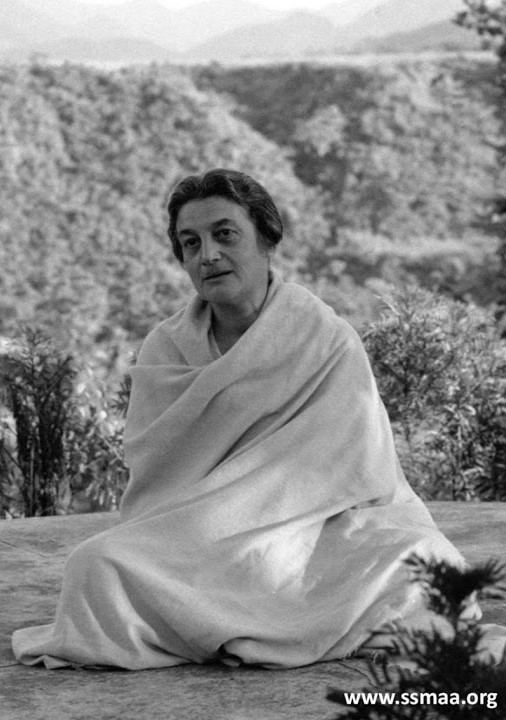

Blanca Schlamm (Atmananda) (1904-1985)

Blanca was born on the 7th of June 1904 in Vienna, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman from a Polish family and her mother was from a Czechoslovakian family. There were early tragedies in her life. When Blanca was two years old her mother died after giving birth to a baby girl. This girl, Blanca’s beloved younger sister, died of diphtheria when she was 17 years old, shortly before Blanca’s 19th birthday. Blanca and her sister had been lovingly cared for and provided with the comprehensive education that their father wished for them. They had one tutor who spoke only French until the children were fluent in that language, and then another who only conversed in English. They had music lessons at a young age and were taken to concerts and operas. Aged eight, Blanca already showed outstanding musical talents.

The best available grand piano was bought for her and she took her practice very seriously, becoming a prodigy and giving her first acclaimed public recital when she was 16 years old. At an early age Blanca became interested in literature and read widely. Before the First World War, Vienna was the capital of a Central European empire, with a very rich cultural and intellectual life; the city of Freud, Klimt, Mahler, Kreisler, Mach, Wittgenstein and Popper. After the war, the empire was dismantled by the victorious allies and a poverty-stricken Austria was the result. Blanca’s family became poor and Vienna became the oversized capital of a small, mostly agrarian state. When she was 16, while walking alone through a park, pondering the senseless destruction around her, one of the defining moments of her life occurred. “Suddenly, all matter – trees, rocks, the sky, water – was vibrantly alive and filled with a divine light in which there was no separation between the seer and the seen, but only an ecstatic unity which was by definition eternal love.”

For one timeless moment all this was overwhelmingly revealed to her and this revelation was to be the driving force of her life from then on. It is interesting to note that the great Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach (1838 – 1916), had a very similar experience aged 17-18, which completely shaped his subsequent life and philosophy.

Many people in Vienna were disillusioned and some had turned to the Theosophical Society (founded in 1875) to satisfy their thirst for knowledge and certainty. The leaders of the Society had proclaimed the young Jiddu Krishnamurti (JK 1895 – 1986) as the ‘Vehicle’ for the anticipated World Teacher.’ The Society made JK the head of one of their internal groups called ‘The Order of the Star in the East.’ JK had been educated and trained by the Society to fulfill this role and had started his world travels, visiting Vienna in 1923. He was an intelligent, charming and attractive young man. Blanca had been brought up to critically examine statements and views presented to her, the mind being considered the ultimate arbiter. She had been attracted by the teachings of Theosophy, had joined the Vienna branch and had quickly reached the innermost circle of the branch. It was at that stage she decided to keep a diary to record her spiritual work and progress. The first entry is ‘Vienna 21st April 1925’ when Blanca was nearly 21. The diary was written in English and, with breaks, contains some 800 entries.

The Theosophical Society celebrated its 50th anniversary at its headquarters in Adyar, Madras in December 1925, with more than 3,000 delegates from all parts of the world. Blanca attended this, on her first trip to India. There she met the leaders of the Society and was enthusiastic about Theosophy and her progress in this system of belief. She returned to Vienna in February 1926 from where she moved to Huizen in Holland where she became organist to the Liberal Catholic Church, a Christian group in the Society. Nearby was Ommen, where the Order of the Star held an annual summer camp attended by members from all parts of the word and by the Society leaders including JK.

Blanca threw herself into the various activities of Theosophy including attendance at Ommen. She became more and more attracted to JK and his teachings. At the 1927 camp JK declared that he had become united with the ‘Beloved’ (the Universal), his individual self having been destroyed. At the 1929 camp, JK made his famous speech, declaring that “Truth is a pathless land and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever.” He then dissolved the Order of the Star in the East. At one stroke, JK had destroyed the foundations of the Theosophical Society, its hierarchical structure, as well as the search for and reliance on external assistance in spiritual growth. This iconoclastic approach, which JK followed for the rest of his life, caused enormous distress and division to members of the Society. Blanca was terribly upset at many of her previous beliefs being shattered, but she was very impressed by JK’s actions and words and decided to terminate her church commitments and returned to Vienna in 1930. The last entry in her diary for that period is ‘Huizen, 17th August 1929.’

To India as a Teacher (1930-1943)

The years 1930 to 1935 were spent in Vienna, giving piano lessons, performing, and continuing with the devotion to JK’s teachings. JK had started an experimental school situated in a beautiful pastoral spot on the Ganges on the outskirts of Benares at Rajghat, for students and teachers to live according to his philosophy. There was a shortage of suitable teachers, so Blanca was requested to go there. She arrived in India in 1935. Blanca’s teaching ability was highly praised. In addition she gave classical music recitals of piano on All India Radio. In trying to implement JK’s teaching, which denied all authority and gave apparent freedom to teachers and pupils, Blanca began to see the shortcomings of his philosophy. By the year 1939, when she saw JK for the last time before the Second World War (which JK spent in California), at his Rishi Valley school in South India, she had reached breaking point and felt she could not give him her previous full support. However, both his teaching and personality continued to influence her until the last time she saw him in 1961.

In 1942 Blanca decided to go to Tiruvannamalai, South India, to see Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi, hoping that he would be able to give her the peace of mind she had been unable to obtain from JK’s teachings. She stayed for about six weeks. After an interval of over 12 years, her diary recommences with an entry ‘Ramanashram, 17th May 1942.’ Whilst there, Blanca felt peace and the power of the higher Self; talked to other seekers; visited the mountain Arunachala and had various visions and dreams. She greatly benefited from the experiences she had there, but the mental obstacles caused by her upbringing, experience of Theosophy and JK’s teachings still remained. Aware of these obstacles and with tears in her eyes, she asked Ramana Maharshi why she could not get rid of her egotistical resistance to his teaching. His reply was: “Take the resistance into your heart and keep it there!” The entries in the diary show that Blanca did not fully understand that the heart was Ramana’s term for the innermost Self, whereas Europeans view the heart as the seat of the emotions. It appears that the latter interpretation was uppermost in Blanca’s mind and it would take many more years before she fully understood Ramana’s meaning. Throughout the rest of her diaries Blanca makes reference to Ramana with deep reverence and affection, but her destiny was to become the disciple of another guru.

Initial Discipleship and the Last 12 Years at Rajghat (1943-1954)

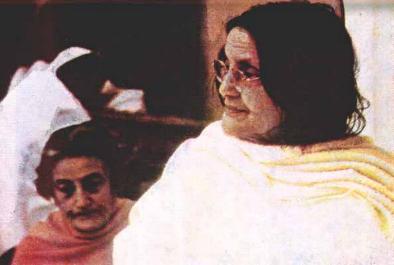

The guru whose disciple she was about to become was Anandamayi Ma (1896 – 1982), referred to by her followers as Ma (Mother). She was one of the most outstanding religious figures in modern times, and was the last great representative of the Hindu renaissance that began with Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836 – 1886). Ma was born in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) and had from her childhood exhibited the most amazing spiritual maturity and beauty. Her consciousness was completely non-dual and she considered her mission to be the preservation of genuine Hindu religious and philosophical traditions which were under attack from the materialism of the West. She had more than 30 ashrams in India and Bangladesh (after partition), and spent her adult life travelling and visiting each as the spirit moved Her. She had an ashram at Bhadaini in Benares, near to Rajghat where Blanca was teaching. Blanca wanted to visit Ramana Maharshi in Tiruvannamalai again, and possibly also Sri Krishna Menon, another highly respected guru who lived in Trivandrum, South India. However as she still had German nationality during the war (Austria having been annexed by Germany in 1938), travel restrictions were imposed on her by the authorities, and she could not go. In the summer of 1943, whilst Blanca was at the hill station of Almora, she was urged by a friend to visit Ma who was there with some of her devotees.

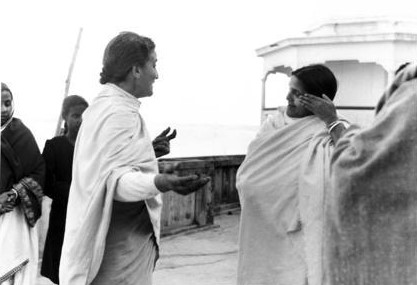

Ma addressed a few words to Blanca, but as the former spoke Bengali and not English, there was no opportunity for a conversation. Blanca noticed that she had not been treated as a stranger, rather as though she were an old friend and she was impressed by Ma’s joy and beauty, also the inward beauty and purity that shone in the faces of some of her devotees. Later that year, Blanca met Ma again in Benares, but Ma was in the middle of a large crowd of singing and dancing devotees, which disturbed Blanca; nevertheless she felt that there was something very special and fascinating about her.

Another person who played an important part in Blanca’ s spiritual odyssey, was Lewis Thompson, an English poet of genius and a spiritual seeker in the same age group as Blanca. His quest had taken him from Europe to Ceylon and India, where he had met and stayed with many of the outstanding gurus of the time. He had a very artistic, sensitive and unworldly nature, as well as a critical and razor-sharp intellect. As a result of his experience, he had an intuitive ability to distinguish between true and false gurus. In the winter of 1944, Lewis came to stay at the Rajghat school as he was anxious to resume his spiritual enquiries and to meet Ma and other teachers in Benares. He was the only other Westerner with Blanca at the school, so a friendly relationship started. This lasted till Lewis’s death in 1949 and had many ups and downs. Blanca admired her friend’s poetic ability and great spiritual knowledge, but was appalled by his changes of temperament and inability to look after his worldly wellbeing. Conversely Lewis was free in his criticism of Blanca’s spiritual endeavours, but supplied Blanca with sound advice on those spiritual topics of which she was ignorant. They were spiritual soul-mates and because of Lewis’s unworldliness, Blanca helped her friend financially like an older sister. It was Lewis who persuaded Blanca to pursue her relationship with Ma.

Through the good offices of a translator Blanca had her first lengthy and private conversation with Ma on 24th March 1954. Ma did not commonly give spiritual instructions but only to those persons with whom she felt a spiritual connection, a connection which was divinely inspired rather than the result of her personal desire or will. Under these circumstances, any instructions which she gave were designed to meet the specific needs of the enquirer. These instructions entailed the transmission of a subtle but quite profound power which the recipient would be enabled to follow. For Blanca this was the beginning of the guru-disciple relationship. Blanca first explained her spiritual history and background. She then asked questions as to how to resolve the conflicts in her mind; very similar to the question she had addressed to Ramana Maharshi. Ma explained that as long as the mind was turned outward to the world, conflicts were inevitable. It was necessary to turn the mind inward, dwelling on that which is permanent, to make it steady and quiet. She explained that at this stage of Blanca’s life it was not necessary to withdraw from worldly activities, but the time would come when solitude became imperative. For the present spiritual practice, Ma recommended meditation building up to three hours daily, breathing exercises, enquiry into what is permanent and what is fleeting and discrimination between these.

Blanca should keep a daily spiritual diary, recording her experiences, her feelings and the changes in her outlook. All her experiences should be viewed as a spectator, both the ups and the downs. Blanca was questioned about her attachments and told Ma that music was the strongest. Ma felt that this was not a problem. She also encouraged Blanca to discuss these matters with Lewis. Blanca had the impression that Ma wanted to help Lewis, using Blanca for that purpose. Conversely, it may be that Ma had asked Lewis to help Blanca. Blanca recorded in her diary after the interview that Ma was completely convincing. Blanca felt that it was not another person talking to her, but her higher Self talking with her normal self. Ma’s words were the outer expression of something taking place at a much deeper level. It was an experience beyond words, but all the more real for that.

Blanca immediately followed Ma’s instructions with some success, but within three days doubts arose in her mind, due to the conflict with JK’s teaching at that period, which deprecated formal meditation. The diaries now record her continuous spiritual practice, her frequent talks with Ma and Lewis, her frequent visits to various of Ma’s ashrams and her many difficulties. These difficulties arose because she could not reconcile JK’s teachings with those of Ma. Her European background was offended by the dirt and noise and by the lack of privacy and proper sanitation. Her classical music background initially prevented appreciation of the Indian devotional music and singing. Finally, the orthodox Hindu rules made her feel unwelcome and an outcast in some of the ashrams. There was much pain, and tears flowed on many occasions. Blanca had been trained since childhood to judge for herself and therefore found the requirements to obey the guru’s instructions, whether she understood the reason for these or not, to be contrary to her personality. This and what she considered to be the unfairness and unreasonableness of some of her surroundings, caused Blanca’s strong temper and anger to rise, leading to friction with some of the ashram’s inmates.

Sometimes she suffered from lack of sleep due to the lack of privacy and the constant travelling. In November 1945, Blanca experienced an inner change, which made her more reconciled to her many problems. She had an unearthly vision of Ma when she was in her company, which reminded her of her mother who had died when Blanca was two. Ma now became her mother and her beloved. She was the ideal of all her devotees and personified what Blanca had longed for, for the last 15 or 20 years. Ma gave her a new name, Atmananda; this is how she is referred to in the rest of this article. In May 1946 she was allowed 14 months leave of absence from Rajghat; she wanted to follow her quest more fully, without having to attend to her teaching duties. She started to live in the Calcutta ashram and to travel to various other ashrams with Ma. Atmananda who was fluent in English, French and German, started to learn Hindi and Bengali, so as to be able to talk to Ma and to integrate with the new life. She was given a mantra initiation by Ma and learned to treat outer events as part of an external drama. She was also able to converse inwardly with her guru, which helped her in the many periods when she could not be together with Ma. Gradually Atmananda’s ego began to shrink, although many difficulties still arose in daily living. Atmananda had many friends in India and the West with whom she conversed and corresponded. These friends followed her experiences with great interest and some of them wanted to know about Ma for themselves. At this stage she decided to apply for Indian citizenship, which in due course she obtained.

In July 1947 she returned to Rajghat. Because of her problems, she discussed JK and his teachings many times with Ma. Ma had no difficulties with JK’s teachings on self-awareness, observation and analysis, but for her this was only one of many important spiritual practices. Her view was much wider and deeper than that of JK. Ma’s advice to Atmananda was to continue with her spiritual practices and to remember that she belonged to Ma; apart from that she could read or think about JK’s teachings whenever she liked. At the end of the Second World War, JK recommenced his international speaking trips. In December 1948 he was in New Delhi and had a meeting with Ma in the garden of the home of Atmananda’s childhood friend Kitty, wife of the prominent Indian politician Siva Rao. The diary summarises the conversation between Ma and JK as follows.

Ma said, “Pitaji (respected Father), why do you speak against gurus? When you say one does not need any guru, sadhana (spiritual practice) etc., you automatically become the guru of those who accept your view, particularly as large numbers of people come to hear you speak and are influenced by you.” JK then replied, “No, if you discuss your problems with a friend, he does not thereby become your guru. If a dog barks in the dark and alerts you to a snake the dog does not thereby become your guru!” This conversation sheds light on one of JK’s peculiarities. At his public meetings he always emphasised that he was not talking at his audience, i.e. making a speech, but was simply carrying on a conversation with them. In most cases this was a ludicrous assertion, because JK’s talks were mostly one-sided leaving little opportunity for anyone to respond. Even if there was a response, JK nearly always made negative comments about any questions or remarks addressed to him. It seems that this policy of JK was the result of his claim that he was not a teacher, having abandoned that role in 1929. Ma by her remarks, showed to JK that this attitude of denial was a self-delusion.

In January 1949, JK came to Rajghat and met Atmananda for the first time since 1939. She had been terrified anticipating the meeting, but though they treated each other politely, she found him to be at a lower spiritual level than Ma. She felt that JK was the Theosophical Messiah, a Westerner who had only a limited understanding of the depth and breadth of the Indian religious and philosophical tradition. Later, JK made negative remarks about her association with Ma and suggested she should leave Rajghat. However, another five years were to elapse before this took place. In June 1949 whilst she was at Ma’s Solan ashram away from Benares, Lewis died in Benares. She knew he was penniless and believed he had died from overeating after a period of starvation. She was extremely upset and believed that for a period after his death he was still near her to give her guidance and comfort. Lewis had made her his executor and had left her a small image of the child Krishna. In 1950, Ma taught Atmananda the ritual of worshipping this image, using a mantra, sandal paste, water, fruit and flowers; she then performed this ritual daily. It brought to her memory that in 1929 when she left Huizen, she had said that she would never perform rituals again. She had clearly moved on since then. She adopted Indian dress, learned Hindi and Bengali, began to appreciate Indian music and felt less out of place in the ashrams.

Full Discipleship (1954-1985)

Atmananda’s increasing involvement with orthodox Hindu society inevitably changed her ability to continue at Rajghat. Exactly nine years after her first lengthy interview with Ma, on 24th March 1954, she was asked by the school manager to leave the school and join Ma in an ashram. Although this was her desire, the practical problems which such a move involved, i.e. no longer having a regular income, losing independence, facing the difficulties of living permanently with non-Europeans etc., had to be surmounted. After discussion with Ma, in whom she trusted completely, Atmananda, aged 50 in June 1954, left Rajghat and her professional life as a teacher and musician.

From that point on, her diary entries become less frequent. She continues with the life and travelling she has experienced since she accepted Ma as her guru, but there are new tasks which she readily fulfils. She becomes the editor of the English version of the ashram magazine, a faithful and almost single-handed duty which she carries out for 30 years. She also translates other publications of Ma and assists other authors concerned with Ma’s teachings. She inwardly thanked her dead father for having provided the foresight and means of learning so many languages. She became a translator for Ma of the many Westerners who more and more took an interest in Ma’s teachings, and of the smaller number who wished to join the ashram. When Atmananda first stayed at the ashrams, she had only Ma to protect and defend her against the problems which arose for her in the strange surroundings. Ma did this task carefully, but was not always available when the problems arose. Now when Westerners came into the ashrams, Atmananda with all her experience and ability, was able to smooth the path for others, to stand up for justice and fairness and help her Indian fellow disciples understand the difficulties which the Westerners faced.

She was at the centre of the small group of Western disciples. She was very glad to have that position, because she realized that the ability to converse and exchange confidences with people of similar background, was invaluable. The last entry in her diary describing her own views, is from Hardwar, 12th February 1962: “Much happens daily in terms of consciousness… To concentrate on the divine in everyone helps solve the problem, whereas reacting only increases the negativity. One should feel that whatever comes is sent by God. Nevertheless, I still get irritated at times. In the evening I could do good work on the new book. How rich life is – so much happens in a single day, although outwardly there is nothing special.”

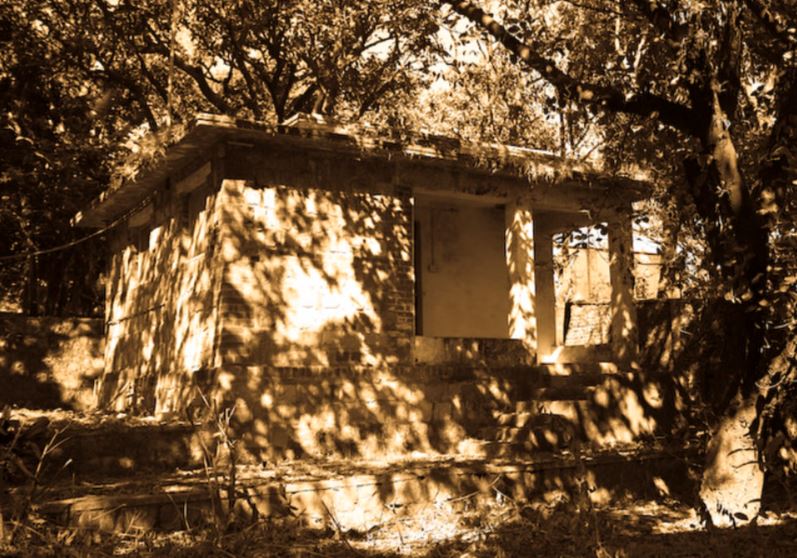

The last entry in her diary is from Kishenpur (Dehradun) 23rd July 1963 and records a conversation between Ma and a French priest. In 1965 a Dutch devotee had a tiny but charming stone cottage constructed for Atmananda in Ma’s ashram retreat of Kalyanvan near Dehradun. It is situated at an altitude of around 2,500 feet in a beautiful tranquil garden surrounded by ancient pine and jackfruit trees, with a view of the mountains. This was all and more than Atmananda ever dared hope for and she remained delighted with the place until the end of her life. Every afternoon she would walk a mile or so to Ma’s Kishenpur ashram to lead the devotional singing which was faithfully attended by a group of local devotees. Dehradun is a fairly sophisticated community and she had many friends there.

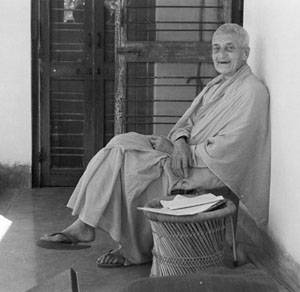

In 1979, on Ma’s instructions, Atmananda went to the pilgrimage town of Gaya to attend the rituals there to mark her formal entry into the final stage of renunciation in which one is completely dead to the world. Outwardly though, she kept this a secret. Ma died on 27th August 1982 and was buried at her ashram in Kankhal (Hardwar). Atmananda was not distracted by the gloom which descended on many of the ashram inmates, but instead appeared to be fired by a new intensity in fulfilling her duties. In 1983, Atmananda’s book As the Flower Sheds its Fragrance was published which dealt with her experiences of Ma. She was also responsible for translating and assisting with the publication of three volumes of Ma’s sayings in English. On the 24th of September 1985, aged 81, Atmananda died of diphtheria in the rest house for pilgrims near the Kankhal ashram; it was the same illness that had killed her younger sister aged 17 in 1923. She died in the sitting position on her bed, softly repeating the name of her guru. At her funeral, she was given the full traditional honours due to her as a Hindu renunciate and her body was submerged in a special area of the Ganges reserved for that purpose. She was probably the only Western woman accorded that honour.

By Hans Heimer, Blanca Schlamm – Atmananda (1904-1985): The Odyssey of a Western Seeker

Richard Lannoy writes in 1996 – She had the longest association of any European – 40 years almost to the day – and played a significant role as the principal interpreter of Anandamayi to the non-Indian world. Her journals, a remarkable account of a 20th-century woman’s spiritual pilgrimage towards her final goal as a disciple of Anandamayi, are currently being prepared for publication. When, as Blanca Schlamm, she became a permanent resident sadhaka, her name was changed to Atmananda, and Mataji allowed her to adopt the ochre robe of a sanyasini in 1962. She was given jal-samadhi, immersion in the waters of the Ganges, a privilege reserved for renunciates, on her death in 1985 at the age of 81.

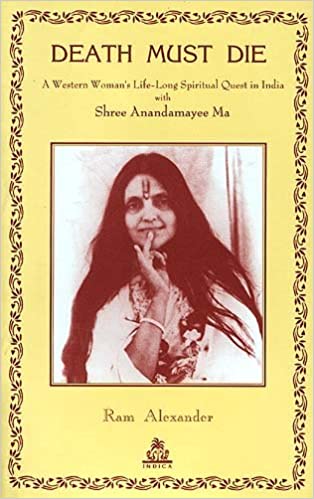

Death Must Die gives an intimate first-hand account of a courageous woman’s spiritual quest in close association with several of India’s greatest modern saints. Ram Alexander, who was a close friend of Atmananda’s and a fellow disciple of Anandamayi Ma, writes with insight about the guru-disciple relationship.

Although written in a diary format, her story reads almost like a novel, beginning with her youthful involvement with Theosophy in the Vienna of the 1920s. In the 1940s she goes to Benares to teach at a school founded by J. Krishnamurti, a close associate. Here we encounter several of her friends and fellow travellers, in particular the English poet and mystic Lewis Thompson who exerted a profound influence on her. Drawn deeper into the heart of Indian spirituality, she encounters Ramana Maharshi at his ashram in South India and in 1945 she ultimately comes into contact with her guru – the great Bengali mystic, Anandamayi Ma, with whom she embarks on the great spiritual adventure of her life as told here-in, culminating in sannyasa, the ultimate renunciation. We are given an in-depth picture of her intense relationship with the extraordinary women. This book is a rare record of a remarkable spiritual odyssey. There are also photos of Ananadamayi Ma, as well of photos of Atmananda, Lewis Thompson, J. Krishnamurti and Ramana Maharshi.

“Looking at Her I felt that she is not a body, but just light. She seemed to see through me with all my shortcomings. All night I prayed to Her: Take possession of me completely, don’t let a particle of me remain.”

Atmananda, as the came to be known, was also closely associated with J. Krishnamurti, and a unique picture is given of him here in comparison with his peers and contemporaries within India. In her almost obsessive desire to “understand” J.K., as she calls him, she was driven ever deeper into the heart of Indian spirituality, encountering Sri Ramana Maharshi, as well as other outstanding Indian sages, before ultimately coming to the feet of Anandamayee Ma.

Although written in a diary format, Atmananda’s story reads almost like a novel, beginning with her youthful involvement with Theosophy in the Vienna of the 1920s followed by her coming to Banaras to teach at Krishnamurti’s school. Here we encounter several of her friends and fellow travellers, in particular the English poet and mystic Lewis Thompson who exerted a profound influence on her. In 1945, she came in contact with Anandamayi Ma with whom she embarks on the great spiritual adventure of her life as told here-in, culminating in sannyasa, the ultimate renunciation. In particular, this book gives a true darshan (an experience of the presence) of Anandamayi Ma and the unique way in which she guided people of self-illumination.

About the Author: Ram Alexander, who was a close friend of Atmananda’s and a fellow disciple of Anandamayi Ma, writes with insight into the guru-disciple relationship and the particular problems that arise when a westerner enters into this within a traditional Indian context.

Some of Atmananda’s the friends included Kitty Shiva Rao, Melita Maschmann, Swami Vijayananda (Dr Abraham Jacob Weintraub), Alice Boner, Lewis Thompson, Ethel Merston, Sujata Sen (Suzanne Curtil), Sunya Baba, Swami Jnanananda, Ella Maillart, Sri Krishna Prem and Lama Anagarika Govinda. The bibliography from A Death Must Die provides a comprehensive list of books by and about Atmananda’s friends and contemporaries, many of whom were Westerners who, like her, spent their lives in India immersed in its sacred culture. These are the pioneers and spiritual ancestors of the generations who have come after them to discover the wisdom of the East. There have been a number of little known but fascinating studies of these outstanding, although in many cases all but forgotten, individuals in recent years (along with other long out of print works).

Kitty Shiva Rao (1903 – 1974?), was a Montessori teacher and theosophist from Austria who, by India’s independence, had led a committee of women to draft an Indian Women’s Charter of Rights and Duties for the new constitution of India. She studied child education and served on several women’s movement and education boards including the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), All India Handicrafts Board, Indian Council for Child Welfare and Delhi University Board.

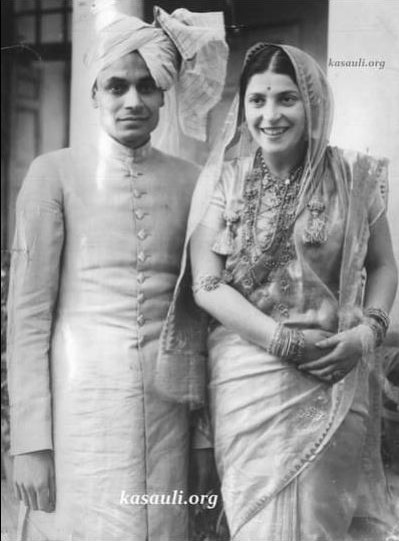

Born into an upper middle-class Jewish family, she spent her early career at the Vienna House of Children. In 1925, she attended the Theosophical Society at Adyar, India, and decided to stay and head a Montessori school in Varanasi, before then establishing a Montessori in Allahabad. In 1929, she married the journalist and Congress politician Benegal Shiva Rao (1891 – 1975).

In 1947, with Fori Nehru (Shobha Nehru, commonly known as Fori Nehru and Auntie Fori (born Magdolna Friedmann; 5 December 1908 – 25 April 2017) was a Hungarian-born Indian social worker and the wife of the Indian civil servant Braj Kumar Nehru of the Nehru family), she helped set up the Refugee Handicrafts employment campaign in Delhi for refugee women in the camps following the partition of India. Later, she co-founded a national programme for the development of handicrafts and handloom products, and continued to promote Indian made crafts later in her career.

Alice Boner was a friend of Atmananda’s.

Disciples of Anandamayi Ma

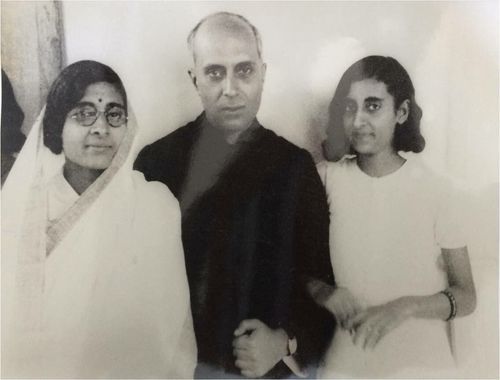

Anandamayi Ma had among her followers many powerful political figures, such as Kamala Nehru (1899 – 1936), the wife of Jawaharlal Nehru, and her daughter Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, as well as scholars like Gopinath Kaviraj (1887 – 1976).

Ram Alexander, a disciple of Anandamayi Ma, describes the rich and educated disciples – These were often highly educated people who faced serious social stigma, especially since it was unheard of to receive such guidance from an “uneducated village woman” (Atmananda 2000: 23).

It is obvious that the presence of upper-class devotees, the wealthy and intellectual elites, played a certain role in the visibility of the cult of Anandamayi Ma (Babb 1988: 170).

A majority of women surround Anandamayi Ma

Women also made up a large part of the community of devotees, and it seems that their number exceeded that of devout men. Far from seeing Anandamayi Ma, the Supreme Goddess above all else, as a source of empowerment or a role model for women, the presence of so many devout women can be attributed to the fact that they might have more access to her body than the men (Hallstrom 1999).

Western disciples very close to Anandamayi Ma

There were also foreign devotees, although their number was much lower than that of the Indian devotees.

The first Westerner to join her ashram in 1943 was an Austrian pianist, Blanca Schlamm, who became a sannyasin under the name Atmananda, and often filled the role of performer.

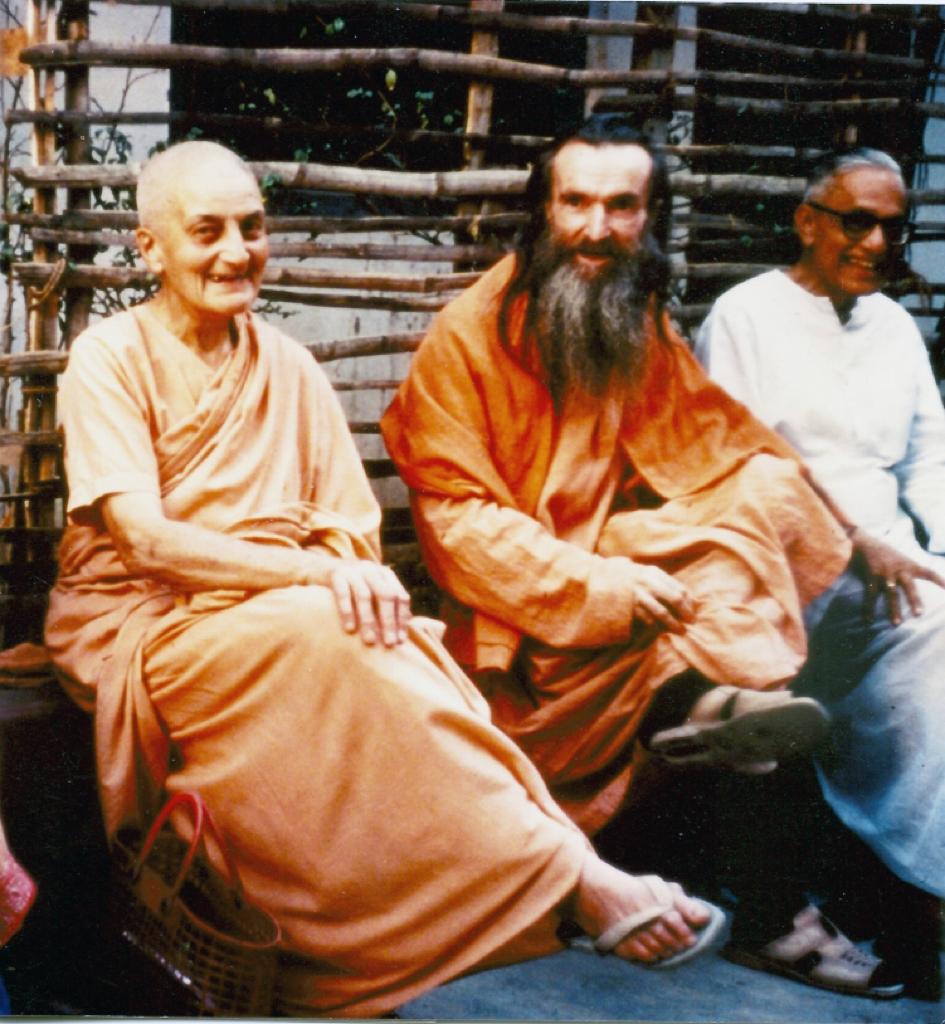

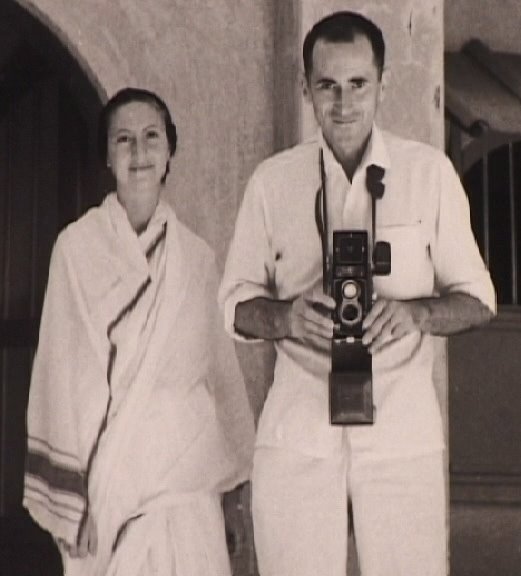

English photographer Richard Lannoy, former French television director Arnaud Desjardins and his wife Denise, German novelist Melita Maschmann have spoken of her in their books.

Among the Western disciples very close to Anandamayi Ma was a Jewish doctor, Abraham Jacob Weintraub, a native of Metz, France and son of the chief rabbi of that city. In 1950, he left France for Sri Lanka and India with the intention of staying only two months. Shortly after his arrival, he met Anandamayi Ma and decided to follow her. Later, he became a monk (swami) in his organization, taking the name Swami Vijayananda (happiness of victory). Swami Vijayananda never returned to France and spent nearly sixty years in India, seventeen of which as a hermit in the Himalayan mountains. Until his death on April 5, 2010 at the age of ninety-five, he welcomed Westerners to the ashram of Anandamayi Ma in Kankhal. Today, Swami Vijayananda is venerated at his tomb in Pere Lachaise, the historic cemetery in Paris, by a group of people who knew him or were attracted to his teachings. He serves as a bridge between East and West, as well as a central figure in the cult of Anandamayi Ma.

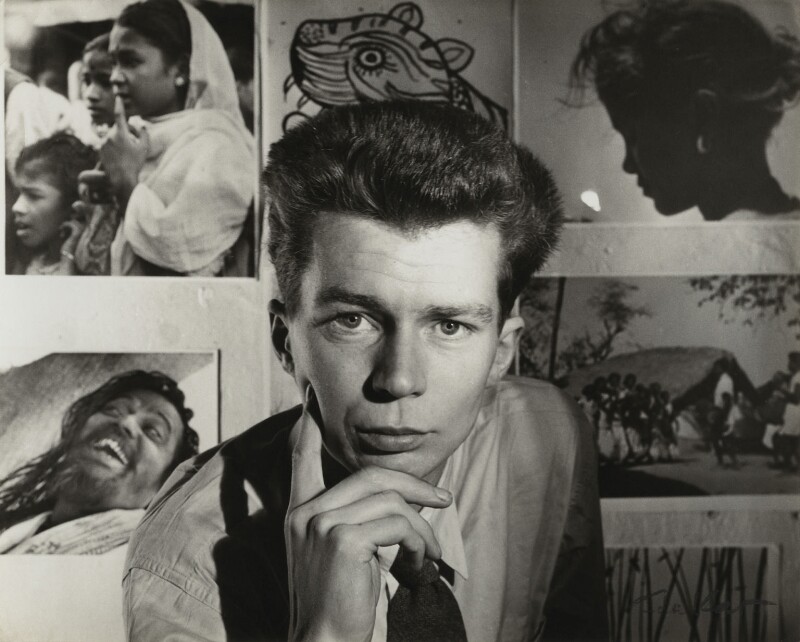

Richard Lannoy

Arnaud Desjardins and his wife Denise

France 1959, Indian spirituality was known only within restricted circles. Arnaud Desjardins, film director and Christian practitioner of yoga, travels to India by car. He intends to deepen his knowledge of yoga. From ashram to ashram, he meets some of the greatest masters of the twentieth century: Swami Sivananda, Anandamayi Ma and Swami Ramdas. He returns with film and writes a book. These two works reveal to a whole generation that another world is possible. Arnaud Desjardins (1925-2011) was a leading figure in introducing the broader French public to the philosophies and religious practices of Asia. His films devoted to Tibetan Buddhist leaders, Indian religious teachers, Japanese Zen philosophers, and Afghan Sufis were widely shown on French television in the 1960s and early 1970s, when such topics were largely unknown among non-specialists. His films were often accompanied by books and later radio interviews and talks.

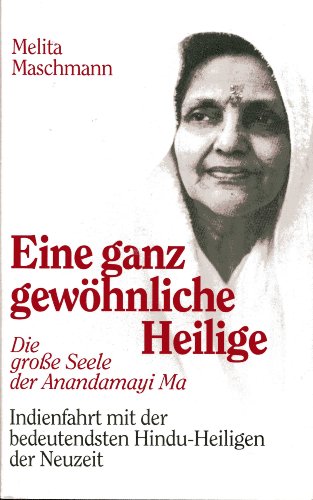

Melita Maschmann

Encountering Bliss – My Journey through India with Anandamayi Ma – This book was first published in 1967 under the title Der Tiger singt Kirtana. It was revised and enlarged and was published in 1990 under the title Eine ganz gewohnliche Heilige. It was also published in paperback edition in 1992. Melita Maschmann, a German journalist, travelled to India in the summer of 1962 and encountered the saint, Anandamayi Ma, seemingly by coincidence.

In the summer of 1962, she wanted to return to Germany, but after traveling in India for a fortnight, “pure coincidence” brought her to Anandamayi Ma. She cancelled all her travel plans, stayed with Ma, travelling through India with her for the next two years. Taking up residency in India, she was given a Hindu name, lived in the ashrams, and only returned to Germany for brief family visits every two or three years. After Anandamayi Ma’s death in 1982, she worked in institutions for children. She returned to Darmstadt in 1998 due to Alzheimer’s disease and died in a retirement home. She was never married and had no children.

The account of her experience with Anandamayi, which is not the product of a mere credulous devotee’s mind but the report of a critical and informed journalist, is so impressive and illuminating, sometimes fascinating, elegant in its style, objective in its approach.

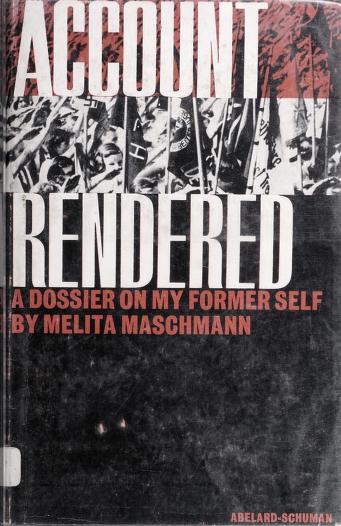

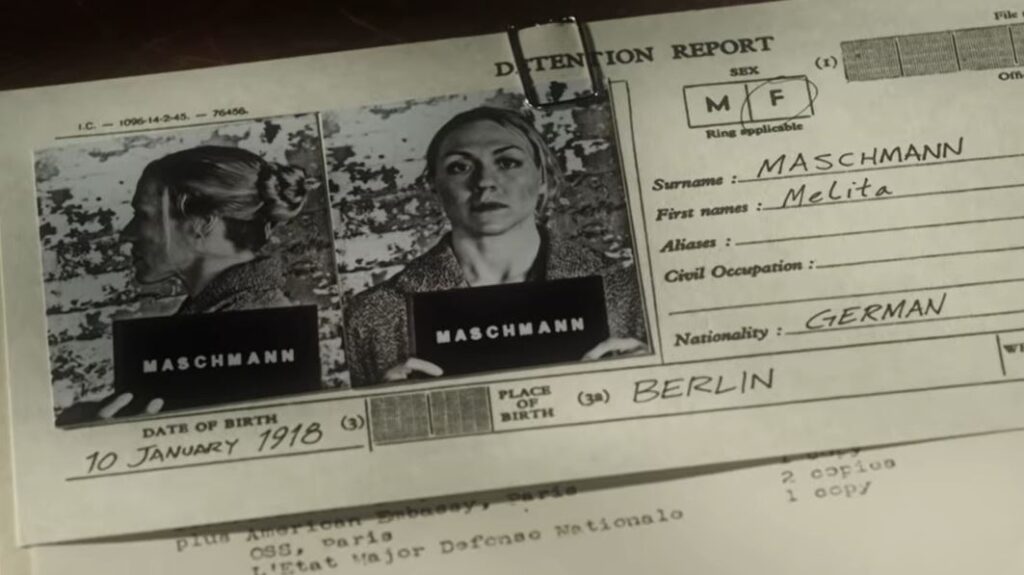

Melita Maschmann was portrayed by Ivy Blackshire in the 2013 documentary Teenage by Matt Wolf. In Teenage we follow Hitler Youth recruit Melita Maschmann from her rise to the rank of Press Officer until she finds herself in personal crisis as the Third Reich falls. Her story, drawn from Maschmann’s own memoir, is voiced by Daniela Leder, and brought to life on camera by Ivy Blackshire.

Matt Wolf was excited to have Ivy portray Melita because she was (and still is) a teenager, and not a professionally trained actor. “Ivy gave me a lot of insight into what it feels like to be a rebelling teenager today,” says Matt. His goal in working with her was to, “help her translate those feelings to Melita’s time and place,” and to infuse the challenging role with a contemporary resonance.

Melita Maschmann: Born Berlin, 1918. Joined B.D.M. (Girls Section, Hitler Youth), March, 1933. Labour Service, East Prussia, 1936-7. Worked full time for press section, B.D.M., 1937-41: Frankfurt-an-der-Oder : Kurmark (in charge); Wartheland, German-occupied Poland (in charge, unpaid). In charge, women’s Labour Service camps, Poland and Germany, 1941-3. In charge, B.D.M. press and propaganda division, Reich Youth Leadership, Berlin, 1943-5. Various war work, including preparation for “Werewolf” (S.S. sabotage) activities, spring-summer, 1945. Captured and imprisoned by Allied authorities, July, 1945. Released 1948. Finally broke with National Socialism in the 1950s. Melita Maschmann later became writer, journalist and novelist.

Melita Maschmann, a journalist by profession, meets Anandamayi Ma by sheer coincidence and travels with her throughout India for several months. This book was first published in 1967 under the title Der Tiger singt Kirtana (A Tiger sings a Kirtana). It was revised, enlarged and published in 1990 under the title Eine ganz gewohnliche Heilige (A very ordinary saint). This book is not only an account of Ma. It is a fascinating account of Melita Maschmann’s encounter with the Divine India, her trials and tribulations, her joys and sorrows in the company of Ma.

Maschmann decided to write an account of life in Nazi Germany. She showed the manuscript to Schweitzer before Account Rendered: A Dossier on My Former Self was published in 1963 (an English translation appeared the following year). It is written in the form of a book-length letter to Schweitzer. In a letter to Hannah Arendt she expressed her desire to help former Nazi colleagues reflect on their actions, and to help others “better understand” why people like her had been drawn to Adolf Hitler. She told Schweitzer: “Even the element of fate in a person’s life does not dispose of individual guilt, I know that. What I hope, dare to hope, is that you might be able to understand – not excuse – the wrong and even evil steps which I took and which I must report, and that such an understanding might form the basis for a lasting dialogue.”

In Germany, the book went through eight editions and was studied in schools. Historians of the Nazi period, including Claudia Koonz (Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family and Nazi Politics – 1987), Daniel Goldhagen (Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust – 1997), Michael Burleigh (The Third Reich: A New History – 2001), Jill Stephenson (Women in Nazi Germany – 2001) and Richard Evans (The Third Reich in Power – 2005), have used the book as a primary source.

Melita Maschmann interviewed by Malcolm Tillis at at a picturesque dharamsala in Kankhal, Hardwar, 29th November 1980, from New Lives : 54 Interviews with Westerners on their search for spiritual fulfilment in India – compiled, edited and mainly photographed by Malcolm Tillis.

MM – First… I never came to India looking for gurus. Ma I met accidentally. How? — you will ask. Then it is for you to listen. In 1962 I was working in Afghanistan as a journalist. Journalists have holidays, so I wanted to spend three weeks with a German family in Mussoorie — that’s where you live, right?

MT – Right.

MM – We started from Kabul — all fine — but by the time we reached the nice Himalayan foothills, the rains washed away the road. That meant their fat Mercedes couldn’t move. I got out, took my bundle and went to Dehra Dun, making myself independent. After passing a boring hour there I asked somebody what would be interesting to see. He said: Take this bus standing at the corner, it goes to Hardwar — that’s a lovely place of pilgrimage. I looked round Hardwar… not so interesting, so I asked someone else on the street. Is there something really nice to see? Much, much — I was told — take a rickshaw to Kankhal: it has an old Shiva temple, and today a fair is going on.

O.K…Right…Fine. There I found a children’s picture-book temple: it is near Ma’s Ashram. I remember this was the first impression of Indian poverty. The fair was going on but there were hundreds of beggars sitting along the lanes, among them many lepers. A little time before, I had changed a 100 rupee note into a clean bundle of one rupee notes; I started distributing them. This caused five thousand beggars to jump at me. I felt as if my last minute had come, oo-ha! Later someone told me that in the same place two years before a Rani had been mobbed to death by these violent people. With their half-eaten faces and hands they were pulling at my bag — they spat in my face: it was shocking. But suddenly two ladies from south India jumped into the crowd, and with great energy howled and pushed and beat these people. They saved me and my handbag — I suppose the poor things thought there must be millions in it. The ladies scolded me terribly — yes, quite terribly — not to give money, otherwise they run after you.

Anyway, they had saved me. Then as they had just come to Hardwar we stayed in a nearby hotel together. We had a nice talk — not too long — they jumped up saying: We have to quickly go to our Ashram to see our guruji — wait for us, we shall be back in an hour. They pointed to the Ashram — in those days it was the nucleus of today’s Ashram. I had never even heard of an Ashram or a guruji: I thought may be it’s a dentist or something like that.

You live in India so you will know whenever anyone says ‘wait for me one hour’, it means between one and four hours: it does not mean sixty minutes. After waiting one hour and ten minutes I became worried so I went to the door through which my lovely ladies had vanished. I knocked hard till an unfriendly young man came out and chased me away by banging the door against my nose. After another twenty minutes I knocked again — I thought perhaps they were in trouble, so late they were. This time one of my ladies saw me and made them let me in. So now although I was inside, I could see everyone was quite content to wait a few more hours, but at least I found out they were not waiting for the dentist but their spiritual teacher. I was much relieved.

One very old lady then came out and offered me a glass of water; someone told me she was the mother of the guruji, Didi Ma — but by myself I would not have been able to make out if it was a man or woman so old was she with a shaven head, sanyasi clothes and toothless smile — a sweet smile. Eventually we were allowed to go up to the roof where we again prepared ourselves for more lovely waiting. We were about twenty-five people.

Then suddenly Ma came out and went up and down, up and down. It was my first intensive impression of this type of people I had ever had — they were a category of entities I had not met before. They started bowing down — pranaming — ecstatic, and Ma chatted with them, laughed with them. Someone forced me to put a question — I had no desire to ask anything — but somehow something came out. The reply was translated by one of the sadhus. It was in such a nice Indian-English that even one syllable I did not understand: to this day I do not know what Ma said to me at this first meeting.

What I did know was that I was absolutely fascinated by what I saw although I had no idea of its significance. I am from a Protestant background, and that anyone saintly is moving amongst us in a physical body seemed to me quite out of the question.

When we got back to the hotel, the two ladies asked if I had an alarm clock: they explained they had to go back to the Ashram so they must be up by 4 a.m. I laughed and said: I will be your alarm clock because I hardly sleep. The fact is that for years in spite of taking heavy drugs I was unable to sleep soundly. That night after seeing Ma was a great turning point for me in many ways, and one of them was that the annoyed ladies had to wake ME at 6. Since then I have never had to take anything to encourage sleep. Now I had nearly 3 weeks before I had to go back to Kabul, so I decided to circulate round this saintly phenomenon and study it.

I was told to carry out the process at Ma’s Ashram in Dehra Dun where she was to arrive in 3 days. Here I would be able to look at her closer for, they said, fewer crowds come. By then, Atmananda, who is Ma’s oldest Western devotee, had given me some information and said: “You ask Ma questions and you will see how wonderful are the answers!” I had no desire to do this but when I started I made a list of 15 philosophic questions.

Then a funny thing happened: when I came into Ma’s room, there was a lady and a boy involved in an intense angry talk – it seemed to me a non-problem: should the boy drink tea or coffee? I thought….Oo-ha!…all this fuss about so little. But I sat down with Atmananda; Ma was lying on her cot watching everything, but she said to Atmananda: What’s all this?

Atmananda showing all the question-papers said: Ma, she has a long list of questions. Ma said sweetly: Bolo, bolo! (Speak up!). So it started. By the way, this was all eighteen years ago so I don’t remember any of those questions, but Atmananda prepared, held the papers up, and out came number one question!

When Ma heard it she started roaring with laughter. I was slightly irritated, but anyhow… Atmananda read on. Number two question. Then three and four, but not one got answered — Ma just laughed loud, played with her hair, her toes, looked out of the window; she was just laughing, laughing, laughing. This went on from question to question. I got more and more angry until about question number nine… I thought: Either they are fools or I am — I’m not in the right place here, let me go!

Taking my unwanted questions from Atmananda, I said bye-bye, and out of the room I went straight for the Dehra Dun railway station where I made a reservation for the night train to Delhi. It was a long wait, so by the afternoon I thought: Let me go back and see what is going on with these laughing people? I slipped in a bit shy as I didn’t want to get nailed down, but I found Ma sitting with a crowd in front of her — she was giving darshan. She saw me, made intensive movements: Come here, come here! She pushed the people away and made me sit down. So I sat for some time and I must say I again found it as fascinating as before: the way she was with the people. Their devotion and bowing down was strange to me, but I was caught again. From time to time Ma threw a quick glance at me from the corner of one eye, and each time, out came the laughter again.

In spite of this I never took the night train: I stayed the full three weeks with Ma. Now although she must have seen me several times each day, every time it was like my appearance caused a button to be pressed and burrrr… here was the laughter again! Well, I thought, it can’t be helped. I couldn’t understand why I produced all this merriment in her and I have never asked her. In course of time — Oo-ha! — this stopped being our only form of communication.

When my three weeks were up I decided to wind up all my work in Germany for some length of time — one or two or three years, to be near this exciting phenomenon.

MT – I believe you have written a book in German on Ma.

MM – Yes. I was a journalist for long years and had written a few books. After I had stayed a year with Ma I found my daily notes just required a little editing and they were published in that form.

MT – When did you decide to stay on?

MM – I never decided. After one year I said it’s too little, after two years I stayed three. Then after about four years I didn’t think about it — it just happened that I am here now eighteen years.

MT – Can you speak about the spiritual discipline?

MM -Everyone is given their own form, but Ma stresses that we are not to speak about it, not even among ourselves — it’s secret.

MT – see you haven’t adopted any special form of dress.

MM – I have met so many crooks in religious robes, in the West as well as in India; I have no desire to share their uniforms. I have a great aversion to uniforms. In the generation which grew up with Hitler we were all pressed into uniforms. In the beginning I did wear a white saree here, but I found them unpractical — I always fell about on the staircases. I just wear clothes that are comfortable now. Anyway, I do not live in the Ashram but in this nearby dharamsala. Only two or three Westerners are permitted to live inside. I have never been fully identified with any community — I am not fully identified with this one either. I am an outside insider.

MT – You have now lived here all these years, is it because you are still fascinated by Ma?

MM – That wouldn’t last eighteen years. It’s something deeper, something impossible to describe. After I had been with Ma for some weeks, one day I said to her: I did not come here to love you, I came to learn how to love God — to love God better through you. At that time — yes, of course — I was very fascinated by her, so much so that it tortured me to part from her at night to go to my hotel room. For anyone in her middle forties, such an experience is confusing. But I have seen this happen to newcomers of all ages and both sexes from East and West. It takes time to understand Ma’s irresistible power of attraction; it has only one purpose: to draw towards God those whose lives have but one centre of gravitation.

A friend once said to me after having a first darshan from Ma: You are all like fish struggling on her line. Well, that was not a nice comment, but true in a certain sense. I have often thought Ma has thrown a hook into my heart — if I try to get away, it tears painful wounds. If I follow, its pull draws me nearer to her. Suddenly the point is reached when the external senses recognize Ma unchanged and the inner sense sees only the presence of God.

Perhaps one can say she awakens the ability to love in people’s hearts with the purpose of turning them towards God. I found this turning caused by her as a revelation within me, a liberation. Fascination freed me from its compulsion. To love becomes a source of inner peace, of joy and hope which is free of fear.

Ma is so beautiful because her body is transparent due to the divine light which is the source of all beauty. Years ago I said to her: I am such an extrovert that I cannot see God within myself, but sometimes I see Him in your face. That night I made a note in my diary: During the evening darshan, Ma glanced at me; suddenly her face which had looked tired became radiantly beautiful, irradiated by the inner light. For an hour she sat silent without moving on her couch. No one dared to talk. Each cell of her body vibrated in the joy of mysterious Presence. Is it allowed to try and interpret such a situation? But perhaps when Ma glanced at me she remembered my remark that morning: Sometimes I see God in your face. And there He was, called by my loving longing to see Him.

MT – Can you give a brief description of Ma’s teaching?

She wants everyone — inside or outside Hinduism — to follow their own way but to follow it to the ultimate goal. She is keen that Christians should become better Christians, and many find through Ma they understand the Bible better than before. This makes her happier than someone saying he wants to become a Hindu. She is very conservative, so there is no possibility of this — you have to be born into a Hindu caste.

MT – Are you ever lonely living this new life?

MM – No.

MT – What are the advantages of being with Ma?

MM – As we progress we begin to see there is more peace, more joy, one is able to control desires, fears, the naughty mind — that is some proof that you have the right teacher.

MT – Are you still interested in literature and the arts?

MM – The interest is there but there is no time, and the intensity of interest has left me. If I see some modern painting — yes — I look, but the interest is on the periphery, that’s all.

MT – Do you keep up with what’s happening in the world?

MM – Only superficially — it’s enough. Months go by without me seeing a newspaper. Perhaps you can tell me what’s going on?

MT – Me? Oh, I don’t know either. I live 1,000 ft. above Mussoorie — that’s 7,000 ft. up in the Himalayas — so I never know anything. We don’t even have a radio, but somehow one can live without the news. I am wondering with your temperament if there have been difficulties in your life since you came to live in India?

MM – How can one answer that? We don’t know what would have happened had we remained in our old habits. The difficulties depend on the community in which we live, and ours is especially difficult because as you know Ma follows to a high degree the laws of the Bengali orthodox Brahmins. This makes communication between Indians and non-Indians, the caste and the non-caste…. we Westerners are non-caste…. most difficult. There are always little miseries which hurt through these laws and we get angry and there are tensions. For me there is only one difficulty, and that is that I cannot have such a close relationship with my guru as those born inside caste. It is the cause of much pain at times. But it may also be Ma’s way of rubbing our egos, and I think she makes nice use of it.

Anyway, I sometimes taste a joy unlike anything else I have ever tasted — and I have gone through all the scales of taste. For many years it was a source of suffering that I was not allowed to live in the Ashram, but this dharamsala is only five minutes away so I am outside all the involvements. I am an explosive person so it is possible I would have created trouble for them as well as for me if I had lived inside the Ashram.

MT – One last question: have you done much travelling in India?

MM – Oh, yes — lots — but only following the procession of Ma; she travels, we travel. I have done no sightseeing, though. When I came to India, you see, my time for sightseeing was over.

Atmanada interviewed by Malcolm Tillis on the 27th of December 1980, from New Lives : 54 Interviews with Westerners on their search for spiritual fulfilment in India – compiled, edited and mainly photographed by Malcolm Tillis.

MT – When I met you last month at Kankhal, you were reluctant to give me an Interview — you said you didn’t want any personal publicity. When at last you agreed, we found much to your amusement, nothing had been caught on the cassette. I know you have lived in India for nearly 50 years and that you are one of Anandamayi Ma’s oldest and first Western disciples. But can you tell me something about your early life and what brought you to India?

A – My mother died when I was 2 years old so I was brought up by my father and grandmother. He was Polish, but we lived in Vienna. I was interested in religion very early, but I went through many phases. At school I learned about the Jewish religion, and I got very Jewish. I remember saying to my grandmother: I can’t stay here, you don’t keep orthodox rules — I’m going away! All right — she said — but where will you go? I was 7, so I began to think I better wait.

But by the time I was ten I was an atheist. When the First World War started, I got interested in politics — this lasted a year or two. But I was still religious-minded and began to read Tolstoy when I was 14. That impressed me very much.

When I arrived at the age of 16 I became a vegetarian and started reading Theosophy. But, really, it’s very difficult to talk if you are going to publish everything.

MT – Yes, I know. But only what you wish to talk about will be published. You know, our backgrounds are rather similar: I was also born a Jew of Austrian-Polish parents, and like you I became a musician. Can you tell me how you started your musical training?

A – It was while still a child of 6 or 7. I was considered a wunderkind, although I successfully avoided playing in public. It was at my music teacher’s that I met a girl, much older than I, who was a Theosophist. She gave me some books to read, but I didn’t like them. Then she brought me Krishnamurti’s little book At the Feet of the Master. I didn’t read it. After some time she wanted it back, so I felt I better read it — you probably know it — it’s very short. Well, it had a peculiar affect on me. From that day I couldn’t eat meat anymore. My family thought I’d get over it, but since then — it’s over sixty years ago — I have never eaten meat. It became contagious: my sister became a vegetarian after one year, then my father, and as my grandmother had no choice, she also followed. It was like that.

From then on I became a keen Theosophist. When I was 21 I came to India for the Jubilee Convention at the International Headquarters in Adyar. That was in 1925. Dr Annie Besant and Mr Leadbeater were alive in those days. I should tell you that I had been fascinated by India since my childhood although I didn’t know anything about India. When I first heard the names of India’s two great epics: Mahabharata and Ramayana, I went home from school repeating those words like a mantra. Of course, I didn’t know what a mantra was until much later.

MT – When did you come back to India?

A – Oh, it wasn’t for another ten years… in 1935.

MT – And this time you never went back?

A – I have not even stepped outside India since then.

MT -How did you meet Anandamayi Ma? She could hardly have been so well-known in those days.

A – I was teaching at Rajghat School in Varanasi, and although I had heard much about Mataji from friends who knew her, and I was searching for spiritual guidance, I was in no hurry to meet her. It wasn’t until 1943 when I was spending my summer vacation in Almora that I had my first darshan. The Danish sadhu who lives there one day said to me: “The Holy Mother is at Patal Devi, why don’t you see her on your way back?” The Ashram there was not built then, but I found Mataji sitting in the open on a string cot. A few devotees were squatting at her feet. She seemed all joy and beauty. She addressed a few words to me. She didn’t treat me as a stranger but as if I were well-known to her. At that time I knew no Bengali and only some colloquial Hindi, not enough for a serious conversation. I wanted to know more about her. In those days there were no books on her in English. She was always travelling, never in one place for long.

All my life I had been taught to look at things critically and never accept anything on authority. I knew it was difficult to distinguish between an enlightened being and one with a semblance of this divine state. At that first meeting I was wearing European dress, a solar topi, I carried a hand-bag in one hand and a mountaineering stick in the other. My appearance clashed painfully with Mataji’s surroundings, and I was sensitive to the curious glances of the devotees.

Nevertheless, I was struck by the inward beauty that shone from their faces. After 15 minutes I got up to go, but within a few months I was able to have Mataji’s darshan in Varanasi, where I taught.

This time she was surrounded by a huge crowd under a pandal by the Ganges. This was the site chosen as her new Ashram, although no building had started. Kirtan was going on. I was not used to this spectacular worship and felt out of place.

In spite of the dense crowd and the loud singing and dancing which disturbed me, there was something about Mataji which attracted me profoundly. I wanted to know her at closer quarters, but the chance didn’t come so quickly.

She says: No one can come to me until the time is right. It was, therefore, two years later before conditions brought me closer to her.

It was at Sarnath. I was allowed to spend a whole evening with her on the roof of the Birla Dharamsala. Here there were no crowds, only a few companions and Buddhist monks. It was informal and I didn’t feel out of place. Sarnath had been my favourite place of pilgrimage ever since I had come to Varanasi ten years before. I spent much time there reading Buddhist scriptures, enjoying the peace and wondering how it was that after millennia the presence of Lord Buddha could still be felt so strongly. I never dreamed that Sarnath, where he delivered his first sermon after attaining illumination, would be the setting for a decisive turning point in my life.

I sat quietly by Mataji not wanting to ask anything, just imbibing the atmosphere. Several days passed like this until one evening I had a long private talk with Mataji. What she said was so simple and convincing; no room for doubts. I thought: How strange I had not been able to find this out myself. And yet I knew it was not another talking to me, but my Self conversing with my self. What Mataji said was evidently only the outer expression of something that took place simultaneously at a deeper level.

The next morning we had another talk to clarify some details, during which Mataji asked whether I had to support anyone in my family. Several weeks later I received news of the death of my aged father, the only near relative I possessed. He had died a refugee in America three days after Mataji had talked to me at Sarnath. The time to make close contact with her came when all worldly ties had dissolved. With extraordinary ease and naturalness she had exploded my problem. Where there had been a constant dilemma, now there was a straight path.

MT – Was it from that time you started editing the magazine “Ananda Varta”?

A – The nominal editor I have been only for five or six years, but, yes, I have been doing the work from the beginning. The chief editor, Dr Gopinath Kaviraj, trained me — he was wonderful to me. Anything I couldn’t understand he would explain for hours. I used to think: What a waste of time — if he would only dictate the answer I would use it and finish with it. Only afterwards when he was no longer available did I realize he had trained me to do everything myself. The magazine started in the early fifties and is published quarterly. In those early days I had such an intense desire to know what Mataji was saying that I spent all my spare time studying Hindi.

In a year I was able to talk to her without help. No sooner had that happened than Mataji would often call me to translate for foreigners. I had a unique opportunity to witness many private Interviews which enabled me to get first-hand experience of the universality of Mataji’s teachings and how she modified them to suit each person’s nature, conditioning and needs.

MT – When you were young you were such an accomplished pianist. I wonder if you ever miss classical music now?

A – Every day I do kirtan for one hour, and at every Ashram function also. Of course, this is Indian music. In the beginning when I heard this loud music I would sneak out — I couldn’t bear it as my ear was finely attuned to Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. I think I once told you that when I first came out to India I played piano recitals on the Indian Radio. My favourite composer was Bach, but I also played Chopin, Schumann, Ravel, Debussy, etc. Yes, I gave it all up, but it never was my life really. I was born into another culture and background, but this was no new life that I entered when I came here… you see, I didn’t belong to that life.

MT – You would never go back to the West?

A – No, no, no! No question. But suppose I were deported, I know there would be a quiet place for me somewhere. Even in the West people are living high up in the mountains with no electricity, no running water. One can live the simple life anywhere. If you are meant to live this life, you will live it wherever you are… but I don’t want to go back.

MT – Have you taken Indian nationality?

A – Long, long ago… in 1951. But I have to tell you a strange thing. I don’t have a passport. When I was filling out all the forms, they said: You don’t want to go out of India? I replied: No, what for? So they never gave me a passport… I don’t suppose I can ever leave.

MT – Are you really 76?

A – Yes. I ought to tell you what happened in 1945 when I wanted to spend the Divali holidays with Mataji at Vindhyachal. The war was not yet over, and being an enemy alien I couldn’t leave Varanasi without permission…there was a permit one had to get. I had only just been drawn close to Mataji. So I was anxious that permission be granted. Can you imagine my joy when told henceforth I was free to travel without permission? Since 1939 all my movements had been restricted. As soon as I was free of desire to go anywhere except to be near Mataji, I was suddenly free to go anywhere I liked.

MT – Can you remember something of special interest from those early days spent with Mataji?

MM – I can never forget the Kali puja which was celebrated at Vindhyachal during that first visit in 1945. Mataji was present throughout the whole puja. Her face changed continually: a drama appeared to be enacted on her features. I cannot claim to know how a goddess looks, but she was so radiantly beautiful and so young that night, it surely could not have been the countenance of a human being.

When the puja was over, I didn’t feel sleepy in the least, but I went to my room to lie down. Someone knocked at the door calling my name. An asana — a small meditation rug — was handed to me with the message: Mataji sends you this. It was 4 a.m., the time one usually rises for meditation. How subtle — I thought — Mataji is presenting me with a reminder: this is no time to sleep but to sit in meditation! I went outside to thank her; she was still surrounded by people, but she said to me: You were cold sitting without an asana? This small treasure is still with me although through the years it has become badly worn.

MT – When I Interviewed Simonetta, she had much to say about Ashram hells. Have you gone through any hells?

A – Now you see my place…where are the hells? Yes, in the beginning there are difficulties, but difficulties are a necessary part of the training. People from the West think that when you come to the guru you just bask in the Holy Presence. That’s part of it — the other part is the difficulties. Mataji is often asked about this. She says: Whatever happens to you is due to past karma which has to be worked out. We come to Ashrams from different social and cultural upbringing and have to mix together. Naturally it’s going to cause upheavals. But we take it as part of the polishing.

MT – Perhaps we only see this when the polishing is complete? What do you have to say about the benefits of Ashram life?

A – The secluded life isn’t a thing you choose like going to a hotel. It has to be meant for you. The benefits? I couldn’t live any other life. Where would I go? I could never live with a family.

MT – When did you start wearing ochre robes?

A – You probably know Mataji doesn’t give sannyas to Europeans. In 1962, when I had been with her for almost twenty years, she asked someone in my presence whether he wanted to take sannyas; he was not willing. I said: “Mataji, I can take it.” She replied: “Achha?” So she gave me a robe with instructions how to dye it and that I should bathe in the Ganges before wearing it. My name she gave at the very beginning.

MT – Is that when you started shaving your head?

MM – Oh, that!…no, no, that’s a funny story. Mataji never told me to do that. A few years ago I slightly injured my head; it became septic and troublesome. I asked the doctor to shave the hair off, but he wouldn’t. The wound didn’t heal so I did it myself. The wound healed but I like to keep my head shaved.

MT – With all the literary work you have been doing, does it not keep you away from Mataji?

A – I am now too old to travel with her all the time. It was different in the beginning — I was with her very much, at times going to small villages where they had never even heard of a bathroom. I often had to sleep in a storeroom — on the floor — having arrived in the middle of the night. All that was good; you see, everything depends on your attitude. Yes, there may be Ashram hells, but there are two sides to everything. If you wish to be with such a being like Mataji, you have to be prepared to go through ups and downs. I have seen Rajas and Ranis putting up with conditions they hadn’t met before. It’s hard, but look at how many Ranis come of their own accord to the Samyam Saptah!

MT – Is that the austerity week Mataji holds every year?

A – Yes. The one that has just ended is the 32nd. They started in 1952. You see, Mataji is extremely particular about one thing: Without self-restraint nothing can be achieved. Mataji firmly maintains if we live soft, indulgent lives, nothing can be achieved. She tells everybody there must be self-discipline. She says that worldly pleasures lead to spiritual death. But knowing that most people live like this these days, she started advising them to keep one day a week or at least one day a month to observe strict rules: eat only one meal, don’t smoke, drink or talk unnecessarily, don’t visit anyone but stay at home reading scriptures and meditating.

MT – What were the eating arrangements during this week?

MM – On the first day we only take Gangajal — water from the Ganges. The next six days, nothing until mid-day when a simple meal is served. We are not supposed to take tea or coffee but as much Gangajal as we like. That is most cleansing. In the evening there is hot milk for those needing it.

MT – Why do you drink so much Gangajal?

A – According to what the stomach consumes so will the mind work. When we start this austerity week, the first thing to be done is to clear out the system by drinking plenty of water. Together with the fasting, this clears and tones up the body. For anyone living in luxury, how can they take to the spiritual life? It can’t go together. That’s why many of those coming from the West get ill — they are spoilt by every sort of comfort. I tell you, the hard life is absolutely necessary.

MT – I wonder if you could end by telling us something about the benefits of the spiritual life?

A – Oh, oh, oh — there is no end to the benefits. On the superficial level, just look: there are no worldly distractions, you don’t have to go out visiting people, or doing useless things. Once you give up these things you can live a private life, a life of seclusion. People used to leave their homes and live alone, but this is difficult. Ashram life is the next best thing, although you have to put up with all sorts of temperaments.

I will tell you one last thing. For me coming to India was not really a new life: I was interested in this from the beginning. I never had to give up anything as I was always out of place there.

In the early days Mataji asked me what I wanted.

I said one word: “Enlightenment.”

She replied: “All right. Then sit perfectly still in meditation.”