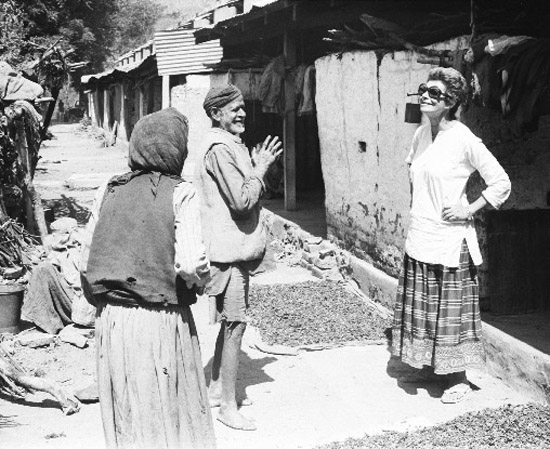

Simonetta travelled in India during the 1960s and 1970s, where she established a colony for the care of lepers as well as a craft training program.

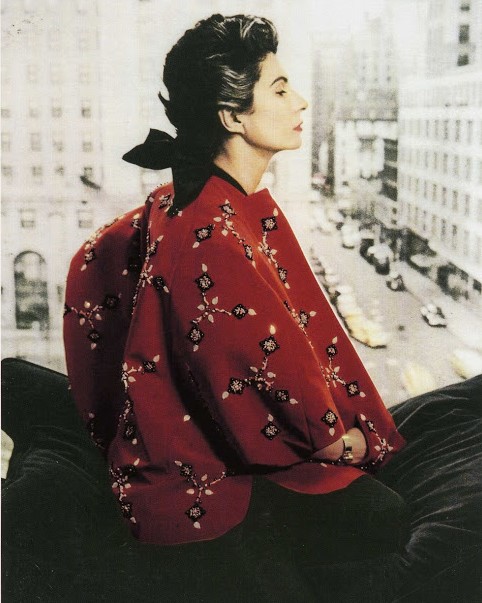

Duchess Simonetta Colonna di Cesaro was born in Rome in 1922. Descended from Russian aristocracy, the daughter of intellectual & politically inclined Giovanni Duke of Cesaro,’ she grew up in a sophisticated environment, and would end up halfway across the world not only geographically, but socially and ideologically, and then back again. Simonetta’s look, her personal life, business savvy and iconic beauty is a great source of inspiration.

While living in Rome she was arrested and detained by Mussolini, freed, married to Gaio Visconti, began life as a fashion designer in Rome, was internationally celebrated as a designer by the age of 24 in Vogue, launched her collections in Paris and New York, adapted her designs with a shrewd eye for sales in the American market with garments in Bergdorf Goodman and then larger chains throughout America, dressed many of the most elegant women in history such as Audrey Hepburn Lauren Bacall The Duchess of Windsor Marisa Berenson Schiaparelli and more, married again to couturier Fabiani her design rival, established the brand “Simonetta et Fabiani,” divorced, launched her Haute Boutique formula in Paris, retired from design, met Guru Swami Chidananda, moved to India in 1970, then returned to live in Rome and Paris.

The First Lady of Italian Fashion interviewed in 1980 said “Ashram life is never portrayed honestly. It is because of the protectiveness of the disciples — protecting the guru, protecting the system — that is at fault. We all know about the blissing-out part. Who ever writes about the frustration-ego-smashing side? There are some marvelous people who are naturally spiritual: there’s no effort, there’s great simplicity, great humbleness. They don’t have to go through the conflicts and excruciating tests we have to go through. We are going through hell; they have bypassed it. The truth I am saying bold and loud.

Perhaps devotee writers feel it their duty to sugar-coat the life-in-the-Ashram pill. Before you take me on a tour of all the Ashram hells can you tell me how you landed in this Ashram? I came only for Swami Chidananda. I met him in Paris in 1969. He was attending a conference. I had just left the Catholic Church for the Russian Orthodox, and my priest was so open-minded that as he knew I was interested in Hinduism he took me to see Swamiji. I had only been converted for one month. The moment I saw Swamiji walk into that crowded room, I don’t know what happened — it was all finished. You cannot explain this sort of thing: you have to pass through it.”

From New Lives: 54 Interviews with Westerners on their search for spiritual fulfilment in India Compiled, edited and mainly photographed by Malcolm Tillis.

Bill has given me much to think about, much to question about my approach to collecting these Interviews. He is now making me a hot drink. I am thinking deep, but not for long. A knock at the door: a dramatic contralto with basso profundo overtones is declaiming the horror of Indian bus travel. The awaited Simonetta is back from a day in horrid Dehra Dun. The aria continues molto staccato: it includes a denouncement of Ashram politics leading into a brilliant caballeta on the well-known theme — The Tortures of Ashram Life.

Simonetta, Roman, aristocratic, totally unforgettable, rises to a renewed pitch of excitement as Bill explains I am longing to meet her so that her Ashram news and views can be included in a book I’m writing.

Just compiling, I correct weakly.

But you writers — she goes on— never tell the truth about Ashram life and…

I quickly interrupt — compilers can only publish the information they are given —

(We have been waiting for the sound of a car outside which would denote Swami Chidananda’s arrival for satsang and which would be our cue to rush out to the lecture hall so as not to miss a word, but without any preliminaries, without asking permission, I turn on the tape recorder, molto rapido)…

…and… I keep telling, and nobody is believing — when will someone write the truth?…the truth that Ashram life is hell! I am also telling — but I know you will never write this — it is not one hell: it is five hells — FIVE! And I can name them all — I have experienced them ALL. Through all the Ashram hell regions have I passed! Is your recorder taking all this down, it’s working?

It is, but there’s not much tape left.

Very well. The continuation can be tomorrow!

Bill, so practical, so helpful, is disgusted at another sign of my all too obvious inefficiency. I have left Hardwar without taking photographs of the persons who gave the first three Interviews; it’s years since I used a camera so I see it as an intrusive weapon, a weapon of aggression I hope to get used to. I am busy trying to cover up my further weaknesses when the sound of a car outside saves me; it is the cue for all the Ashramites to march up to the hall like the tail-end of the triumphant chorus in Act 1 of Aida.

Swami Chidananda is already sitting serene, eyes closed, still: he has the most ascetic face I have ever seen. The radiation of a saint can be overwhelming if one absorbs too much —I know all too well it can make you want to go home and stop compiling accounts, however dynamic, however accurate of the rich variety of scenes from Ashram life. But this Swami is light and joyful and is making me want to hear even more of everything Simonetta threatens to let loose. Or is it that I have lived long enough in an Ashram to share some of her joy and discomfort, her trials and moments of supreme bliss?

…Now as I was trying to tell you last night…and are you listening?… Ashram life is never portrayed honestly. It is because of the protectiveness of the disciples — protecting the guru, protecting the system — that is at fault. We all know about the blissing-out part. Who ever writes about the frustration-ego-smashing side? There are some marvelous people who are naturally spiritual: there’s no effort, there’s great simplicity, great humbleness. They don’t have to go through the conflicts and excruciating tests we have to go through. We are going through hell; they have bypassed it. The truth I am saying bold and loud.

Perhaps devotee writers feel it their duty to sugar-coat the life-in-the-Ashram pill. Before you take me on a tour of all the Ashram hells can you tell me how you landed in this Ashram?

I came only for Swami Chidananda. I met him in Paris in 1969. He was attending a conference. I had just left the Catholic Church for the Russian Orthodox, and my priest was so open-minded that as he knew I was interested in Hunduism he took me to see Swamiji. I had only been converted for one month. The moment I saw Swamiji walk into that crowded room, I don’t know what happened — it was all finished. You cannot explain this sort of thing: you have to pass through it.

Swamiji was the embodiment of everything I dreamed of: the love, the light, the purity, the beauty. I heard all his talks for the next two days. It was a bewildering experience. Then he disappeared. I looked for him everywhere. I could not find where he had gone. Swamiji just disappeared out of my life.

Now I was a very famous fashion designer, and I had a contract with a chain of stores in America for the past eleven years. I had to go there for publicity tours twice a year. I was breaking away from all that so I could concentrate the work in New York: fashion shows, Interviews and so on. My contract was finishing in June 1970, but when I arrived in New York they wanted me to do Chicago and San Francisco also. Fashion didn’t interest me any more so I didn’t want to go to California. But in New York I called up the Divine Life Society to see if they knew where Swamiji was. He was in San Francisco! So my contract — which was to be my last in America — brought me to Swamiji again.

Swamiji returned to India in December 1970, and I flew back to Paris to wind up my affairs. By January 1st I was with him in India. I didn’t know anything about the Ashram: I came only for him.

But why do you find Ashram life hell?

I don’t find it hell — I find it five hells. Are you listening? I tell them to you? The most obvious hell is the lack of minimum comfort…there are buckets of water, and like policemen who have dates for changing into winter and summer uniform, we have dates for hot water in winter. It can be freezing, but until a certain date, no bucket of hot water. Then we have lovely noise, and dust, and food that comes in which you have to heat up — that’s if the electricity is working and the stove hasn’t bust. Here the power fluctuates with much enthusiasm, so everything breaks. There are the pigeons who like doing their nests in the fuse box which also makes it dangerous to interfere with their strange habits.

There is always something extraordinary happening. But all year round we are sure of one lovely unmovable fixture: the food is the same — rice and lentils with a bit of vegetables. At least we are able to boast that food has no longer any importance. Oh, my God, there are so many hells! The animals — we have zoos in our rooms: monkeys and famished dogs trying to get in; ants, scorpions, cockroaches and flies already installed inside; mosquitos having feasted to their fill, wanting to get out. Oh, I forgot the wasps: they also come in to nest. We have to get accustomed to all this. And I must not forget the mice. They are very small, and as no doors fit properly or touch the ground, they stroll underneath: you suddenly see a grey thing that has the cheek to stare at you…he is not even afraid.

But then there is a much subtler hell, a more difficult hell: it is having to live with other people. You have to get along with them and not indulge in likes and dislikes, not to get caught up with emotions and sensations generated by them but to relate to them in a detached way. We are collected together for the same reason but from different backgrounds and cultures. It takes much patience to look on everyone as your brother or sister.

Now do you begin to see what I mean about the hell regions? The more I go on, the more hells come into my mind. Another is — these reflections are all personal, for we are all at different stages of evolution — yes — the loneliness of Ashram life. Suddenly you find yourself living in a community with people you don’t know and with whom you would never have even met in your ordinary life. There is lack of communication: it is not easy. In this solitude comes the lesson — most important — how to live with yourself and not depend on people and objects.

Would you like to say something now about the benefits of Ashram life, or something about Swamiji’s teachings?

Swamiji doesn’t give any teachings — that was my big surprise: he only gives silence — at least to me. Let me begin from the beginning. Having worked for twenty-five years in fashion, I couldn’t see myself sitting on the banks of Mother Ganga doing nothing. I asked Swamiji if I could look after the orphans. He never answered. I had even written to him about this from Paris. Silence. Silence. Silence. By the end of 1972 I was rather demoralized. Someone suggested I try looking after the lepers. I was so wanting to work that lepers and children were all the same to me. Swamiji said I should draw up a programme and join him in the south where he was on tour.

This Ashram here in Rishikesh is surrounded by three leper camps, mostly beggars cut off from human contact, rejected by society. They were waiting for death, passive, sad. I made up a programme, and joined Swamiji. He never looked at the programme, he never called me. I was to fly to Paris, so at the last moment he pulled out the papers, but said there was no time to discuss it – so many devotees were waiting for him. He suggested I extend my visa and wait for him at the Ashram. When he returned we visited the lepers together. We started by taking away all the begging lepers and put them in a camp: Swamiji then measured symbolically the first rations.

From that day that group never had to beg. They have food, medical care and clothing.

At the other camps we started handicrafts — they weren’t obliged to work, it was absolutely voluntary. I then flew back to Paris where I got rid of everything — I had already sold my fashion house after the first trip to India. I was back in the Ashram a few months later, and from fashion, destiny gave me lepers to take care of. I took charge of the medical side: there was no compounder, no dispensary, no doctors — nothing. I learned how to give injections, medicine dressings; it was not easy for me. The dirt — the most horrible wounds that had been neglected, rotting: the sweet smell that never left you, worms eating away mutilated flesh, eyes eaten away by white ants. It would have been impossible for me to have done that work unless I had devotion and love for Swamji. He was working through me: nothing could I have done alone. Only now can I tell you, as you have asked — that was Swamiji’s teachings.

Later, when everything got settled in the camps, and as I was still full of illusions and believed a guru should give so-called spiritual instruction, I started going to someone else for Vedanta instruction. I love philosophy, I am not really a bhakta. I heard Krishnamurti and was fascinated with what he did with people’s minds — he takes the mind and puts it on a higher level; so I decided it was time for me to look for gurus and teachings. I went to the Himalayas, everywhere from Sikkim with Karmapa and Kalu Rinpoche in Darjeeling to Muktananda to Krishnamurti, who became my obsession. I even had the nerve to go to a great lama and tell him I had come to learn so that I could understand Krishnamurti better.

May I ask who you consider your guru or gurus?

First, Swami Chidananda who opened me up to spirituality — and I must say whenever I’m in front of him I am a total idiot: I can only say — Yes — Yes, Swamiji — Yes… Secondly, my other guru is Krishnamurti, who for me is the living Buddha — he is unique. I am very lucky. I have had a lot of gurus — whoever teaches you something is a guru. All my initiations have been from Tibetan lamas — Swamiji has never initiated me.

Now I should tell you that Swamiji told me years ago: This Ashram is your spiritual home in India… you can leave your things here… you can travel and do whatever you want… but remember, this is your home. This is what happened. I have traveled all over this country, but I always come back here.

Bill told me you are building a small house in the Ashram.

Only yesterday Swamiji gave the blessing on the plot of land which had been chosen in 1973.

I see in this room of yours you sleep on the floor and use the bed as a table. You must have lived a very different life before you came to India.

Different it was. Italy was discovered as a fashion center after the war, and in the fifties and sixties I had one success after another. I was practically the queen of Italian fashion. I was constantly travelling round the world. I had everything I wanted: beautiful houses, luxury which I adored, success which I adored, and I made a lot of money which I adored. Then came the change in my life.

In 1962 Christian Dior died. Capucci, the Italian designer opened a fashion house in Paris. It was a success, so he persuaded my husband — who was also a fashion designer, Alberto Fabiani — to also open in Paris. In Italy we had separate houses: his was Fabiani, mine, Simonetta. But we merged our businesses in Paris next door to Balmain, Dior and other big houses. More success. But Paris became the bridge to the East. Our marriage broke down — he was always flying round the world that way, and I was flying the other way: we never met.

I was a tremendous success but all alone. I had three choices: to go to a psychiatrist, throw myself in the Seine, or take to yoga. I met a hatha yoga teacher, and for several years he helped me. But of course, when one starts meditation one’s life begins to change; the things that had appeal and glamour fall away. I started going to the Russian Church — I had always reacted violently against my own Church with its hypocrisy, its system of banging fear into children – fear of hells, fear of heavens, fear of sins: it’s disgusting what they do! For many years I couldn’t step inside a church.

Do you want me to leave all that in?

For me you can put anything that’s against the Catholic Church — I am violently against it. With great difficulty I am only just getting over it.

I ask because…

Yes, yes — I know one shouldn’t, but I’m still very violent you see: I still have strong feelings about this. When I was 14 or 15 I had great spells of fear, and it took years to get rid of them. That is why I have such resentment against the Church.

Would you rather talk about the positive side of Ashram life? I’m sure there’s much that you have enjoyed here.

This Ashram is unique as an organization. We have lovely monks. It is a bit like a sea-port; people come and go. It‘s good for beginners as there are lectures, a library, three-month courses. Residents are allowed to follow their personal sadhana. It doesn’t matter from which country you belong if there’s a deep involvement in the search for the inner life. Since I came here Swamiji has drained me of all my love — I can’t love any more. He has taken it all. I think of him as a fisherman throwing his net all over the world in his travels and catching new fish to bring to the path. Only after many years did I understand what he taught me — there are no teachings, but he taught through his silence.

I have also found that we must learn to be aware of everything during the day; that is a form of meditation. Meditation does not mean to have a rosary in your hand and have your eyes closed. It means to live here and now, to be aware of what’s happening inside and outside. Krishnamurti gives what I call teachings: clues and directions, how to look at ourselves, at things. He gives no conclusions; on the contrary, he puts questions with no answers.

Do you keep up with what’s going on in the outside world?

No, no, no! I don’t read newspapers any more. The only books I read are on philosophy. At first I couldn’t stop reading — it was like a folly. Now I read much less. All books say the same thing — practice! Through practice, I am finding out, the doors open slowly and you get a glimpse that every teacher is showing you the same way in different words.

Bill gave me a lecture last night, so I am going to plunge deep. In your old life you had much fame, wealth, happiness and much misery also. Now, in spite of the Ashram hells, have you made any inner progress?

Progress? Many times I’ve watched a fascinating thing: we are always the same. We don’t change. Maybe with realization there’s a complete transformation. Through our practices we become aware of our emotions, and look at them: but they are there. They are more quiet, they are sleeping instead of awake. So what is progress?

Well, should you have to go back to the West would you be able to re-adapt?

It would be a good exercise. I do go on short visits and arrive peaceful, calm until one has to meet other mentalities, problems. You see that the East has been teaching you, now the West is teaching you: you are always given teachings wherever you are. Once you can take all teachings under all circumstances, then you know you have arrived. But once you have lived in the East and you have loved the East as I do, it is extremely hard to even think of ever living in the West again. You see, I have one big wish left — that is why I have asked for that tiny house here. I want to die in India… to be burnt here and have my ashes thrown into the Ganga.

Apart from this wish do you have a goal in your life?

There is no goal.

Why are you here?

You start looking for the goal, then you learn there’s no goal. There is no seeker, there are no teachings, there are no teachers.

That sounds like Krishnamurti.

Yes — yes — yes, but you have to understand all that. The path is divided in two: first is the ego trip — one wants progress, one forces oneself into all sorts of disciplines. But all that’s the trip of the ego. Second part: we come to realize there’s no “I” — we are just energies, there is no goal, there are no teachings.

You say we are energies, does that mean you don’t believe in karma and reincarnation?

I am studying all that — meditating on what reincarnates. I don’t believe in a stable entity that reincarnates. It’s a mixture of energies that at a certain point crystallize into a human being, and with death, they dissolve. What reincarnates, I don’t know. This is my Buddhist training and ideas. We are still in the field of the mind, so we each project and receive within the field we are working in or believing in.

But isn’t spirituality something apart from the mind?

We speak about spirituality as a thing which can be acquired. It is a gift. All spiritual experiences are given as a gift; we do not achieve them. The spiritual life is to get rid of the ego, the “I”, and to awaken perception and intuition. We all have that potential within us. But for Westerners especially, our minds are so clear, quick — our brains are working all the time: we function through the mind not the heart. Sadhana means to get out of the mind so that perception and intuition can develop. It’s a slow process. People come to India searching, searching. It’s so hard to judge what’s in their hearts, if they are only frustrated or afraid of life or facing responsibility. There are so many problems.

Do you have a problem with your family? Do you ever miss them?

At the beginning my mind wandered from the East to the West like a pendulum. But one has to pull it back into the here-and-now. My son was only 16 when I first came here. It’s an extremely long process getting rid of everything; attachments, material things — they grasp you. It’s not enough to say: I will throw everything away! They cling to you. Mental detachment is all right, but the practical part takes time. It is not difficult for me to stay here — I was never at home anywhere in the West.

At the beginning when we started talking last night about the Ashram hells I missed out one important hell. It is a hell that lies in store for us. It is the hell waiting for us if we ever go back to the West. You see, we suddenly find we do not belong there. That can be a traumatic shock — we don’t know where we ought to be, who our friends are; so much has dropped away — old habits, our old way of living, the old way of thinking. We find ourselves as alone in the West as we are in the East. Yes — we may now have a lovely hot bath, some chocolate, all the things one used to love, but they have lost their meaning. Clothes have lost their meaning, all the things one cared for have lost their meaning.

The taste of the West after many years in the East is a serious hell because it attracts and repels at the same time. The only way is to find the famous Middle Way, the way of detachment.

Simonetta was able to get her own dream house built over-looking the Ganges. Now in her eighties she divides her time between Rome and Paris with visits to India to see her guru, the extremely frail Swami Chidananda who is almost 90. She has completed her autobiography, which without doubt will be colourfully frank, stimulating and controvertial. It is still to be published.

http://www.newlives.freeola.net/interviews/5_simmoneta.php

http://caliente-it.blogspot.com/2012/07/simonetta-first-lady-of-italian-fashion.html