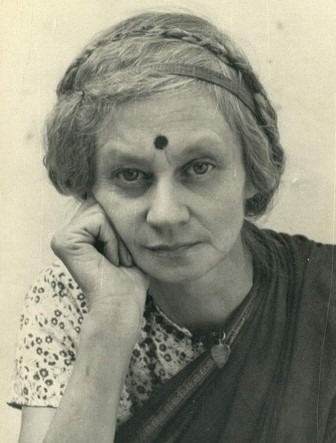

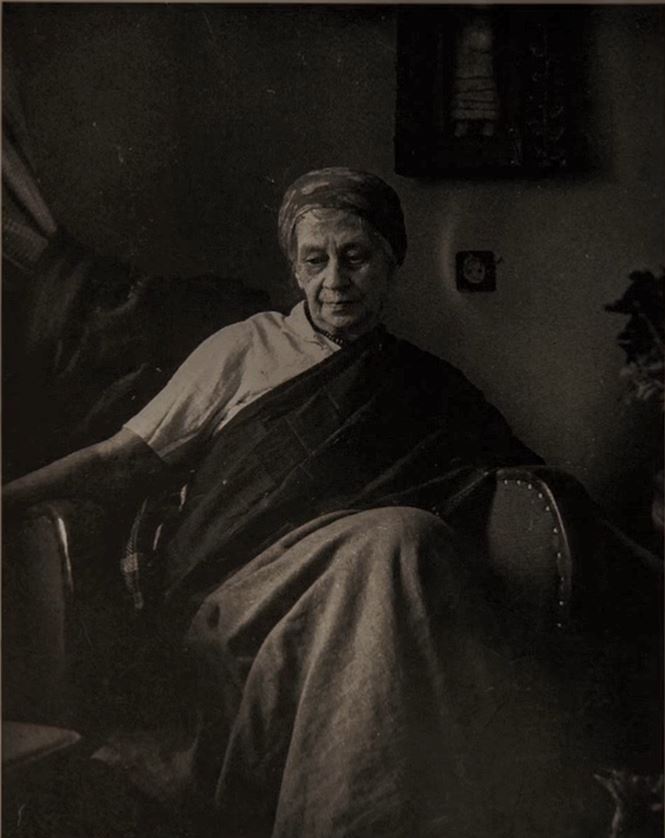

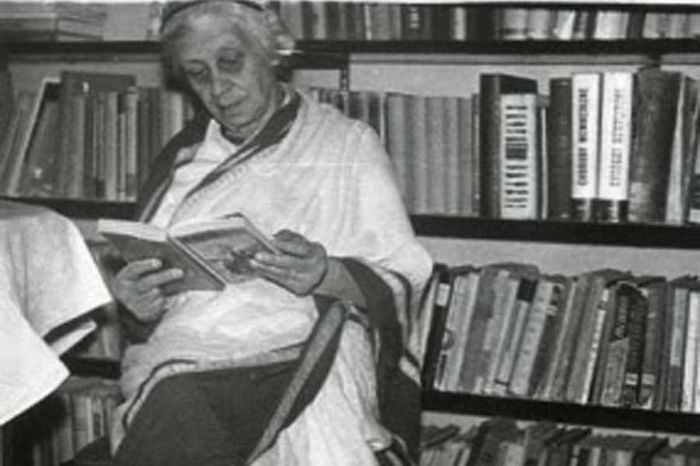

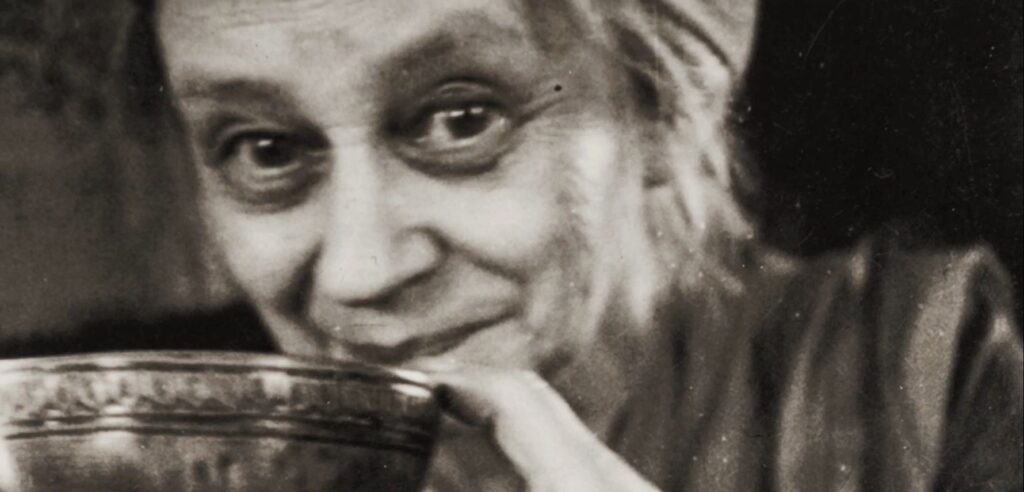

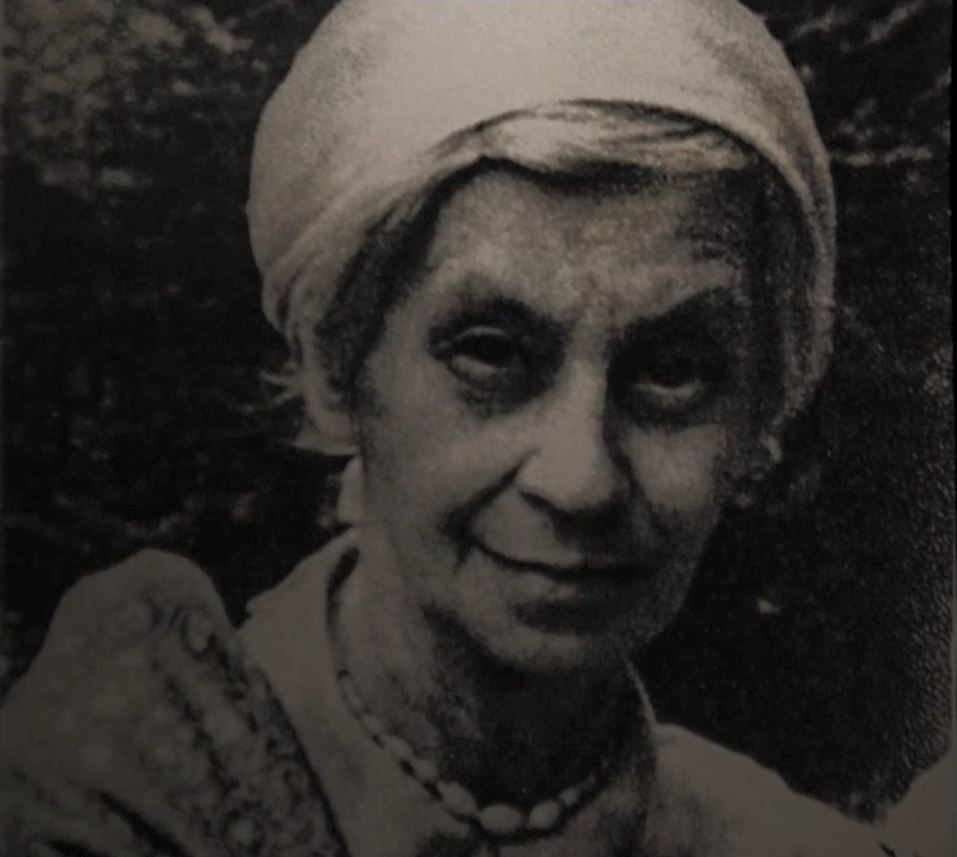

Polish writer Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) (Tenzin Chordon) (1888 – 1971) lived in India from 1935 until her death in Mysore in 1971, often visited the ashram.

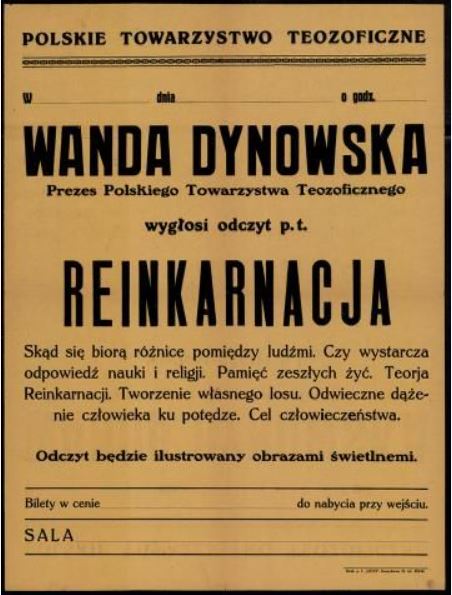

Wanda Dynowska came to India in 1935 on a soul-searching mission. Born to Catholic parents of Polish nobility in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1888, Wanda was drawn to the Bhagavad Gita, the Koran and other spiritual books at a young age. This drew her to Theosophy and particularly to Annie Besant.

While in India she stayed at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar and made frequent trips to Ramana Maharshi’s ashram.

She was a bridge between Poland and India exchanging the richness of their cultures with publications and translations of over 100 books, including the Bhagawad Gita, the teachings of Ramana Maharishi, which attracted many Poles to come to the ashram.

She became a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi who christened her with an Indian name of “Uma Devi.” She raised resources for Polish refugees through the local Maharajas, and set up schools for them imparting Montessori education.

In 1944, together with another Polish visitor to Ramanasramam, Maurice Frydman, she founded the Indian-Polish Library in Madras, which became for more than thirty years a major editorial body for Polish translations of main Hindu religious texts as well as for contemporary Indian poetry and literature.

She was a spiritual seeker donning many hats. She went to north India to study Kashmir Saivism, with Swami Lakshmanjoo in the Ishwar Ashram, a distinctly variant school from that of Tamil Shaivism.

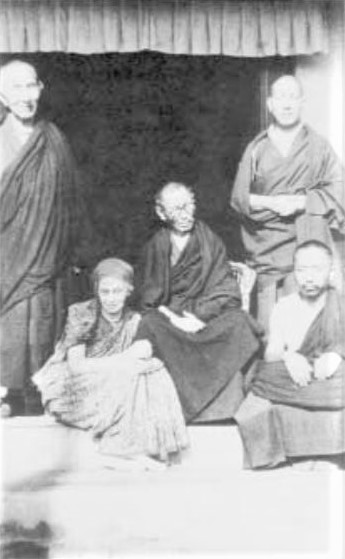

Her meeting with the the Dalai Lama, in 1956, was a turning point in her life, and drew her to a new Path. The Dalai Lama rechristened Uma Devi as Tenzin Chordon after she started to embrace Buddhism.

From 1960, she with the help of Maurice Frydman started helping Tibetan refugees in India. Living in their main centre in Dharmasala, Dynowska organised schools, education, and social infrastructure there. Additionally, she published Polish translations of Buddhist texts. She later settled down in the town of Bylakuppe near Mysore, the largest settlement of Tibetan refugees. The settlement is larger than that of Dharamshala. When her end came in 1971, she requested a Catholic burial, and her tombstone is a glaring memory of her unsung epitaph:

“Here lies a Universal Soul – a Polish Theosophist – Born a Catholic, embraced Hinduism and settled for a service in practical Buddhist altruism. She left behind a footprint which was deeply etched in the sands of time”

This East European Yogi was indeed an epitome of Light and Compassion. She opened the doors of Inner Light in both India and her native Poland.

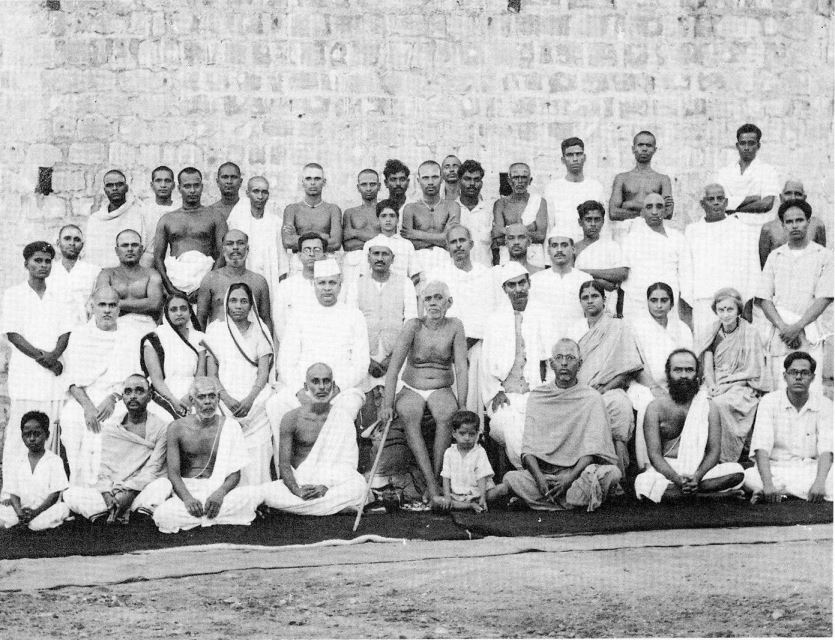

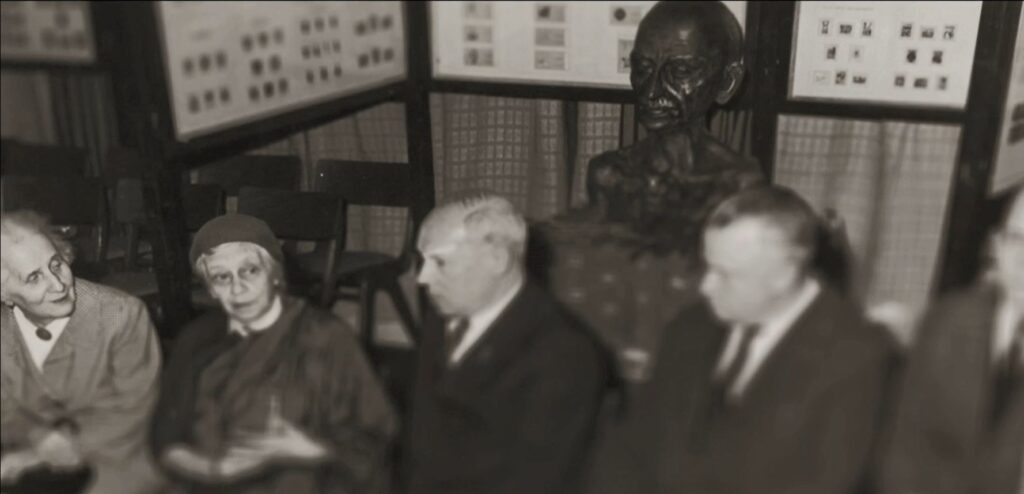

Polish Theosophical Society and admirers. On Mrs. Besant’s immediate left is Wanda Dynowska. The

uniformed figure to Mrs. Besant’s right is General of the Polish Army Michal Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski.

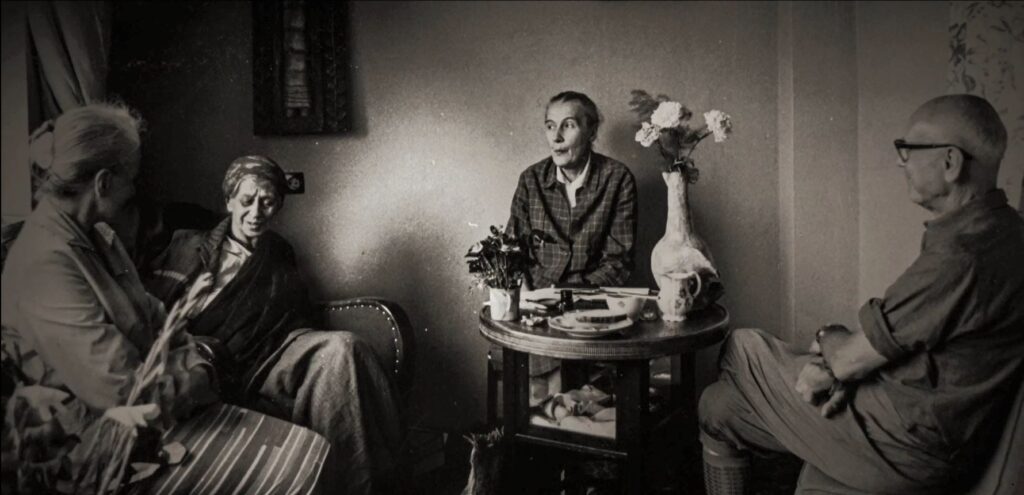

Souvenir photos from a month-long expedition across southern India organized by Wanda Dynowska (seated, center). A group of twenty-five young people gave performances of Polish songs and national dances, while also learning about the culture, art, architecture and traditions of their host country. Their itinerary was Bengalore (today Bengaluru), Trinomalee (today Tiruvannamalai), Madras, Madurai, Tenkasi, Courtallam (today Kutralam), Trivandrum (today Thiruvananthapuram), Nagorkoil, Cape Comorin (today Kanyakumari), Mysore (today Mysuru).

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/passage-to-india-polish-history-museum/zwWBQq9LDKemIg?hl=en

Tibetan lamas. Photographed in 1966 in a Tibetan village near Mysore.

Wanda Dynowska / Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture

Posted by Irene Tomaszewski on June 25, 2013.

What a vision she must have been, this exotic, serene, sari-clad woman who spoke fluent Polish and cared so much about them. She was known as Umadevi, a name given to her by her friend, Mahatma Gandhi, but she was Wanda Dynowska when she arrived in India from Poland in 1935.

In 1942, Dynowska/Umadevi was instantly drawn to the children from her beloved homeland who had found shelter in her equally beloved India. She shared with them what she had: serenity, a dedication to peace and respect for all cultures, and her knowledge of the land and the people that welcomed them.

Dynowska was born in St. Petersburg in 1888, a time when Poland was still partitioned and occupied by Russia, Prussia and Austria. The family spent much of the time on their estate in Latvia, a centre of intellectual discussions and profound Polish patriotism. Educated at home by private tutors, the young Wanda became fluent in Polish, German, French, Spanish, Italian and English, as well as Latvian which she spoke with the local country people. She also spoke Russian, though only when she absolutely had to.

She read the great literary works, the “canon” of the era, and acquired an early interest in Bhagavad Gita, the Koran and the Bible. She was attracted to Theosophy at an early age because it offered “unlimited perspectives; life has neither beginning nor end, it is an everlasting creativeness, an inseparable attribute of the highest consciousness, God.” Dynowska remained interested in the human spiritual dimension throughout her life and studied world religions. For a while, she favored the Liberal Catholic Church in Poland.

She spent 1917 and 1918 in Russia, in the Crimea, making plans for the development of the Polish Theosophical Society, for which she translated J. Krishnamurti’s “At the Feet of the Master.” While in Russia, she spoke French with her colleagues, refusing on principle to speak Russian. Like her close friend, the English theosophist and social activist, Annie Besant, she espoused freedom of thought and speech, women’s rights, and national independence for nations controlled by imperial powers, among them Poland, Ireland and India. When Poland regained its independence in November 1918, she returned to Poland, hosted theosophists from the Paris Society, and undertook lectures on theosophy in towns throughout the country, attracting many members to the Society.

In 1925, together with the Polish general, Michal Karasiewicz-Tokarzewski, she created the Polish Federation of the Order of Universal United Mixed Freemasonry, a form of Freemasonry admitting both men and women that had its origins in France with Le Droit Humain. Dynowska’s lectures and meetings now took her across Europe, to Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, France, Yugoslavia and Great Britain.

From the moment of her arrival in India, in 1935, Dynowska immersed herself in Indian life at many levels: spiritual, intellectual, social and political.

She studied yoga with Sri Ramana Maharishi and frequently returned to the holy mountain Arunchala where she was initiated into deeper levels of Hinduism, and made a pilgrimage to Ishwar Ashram in the Himalayas to study Kasmiri Saivism with Swami Lakshmanjoo.

She wrote prolifically on Hindusim, including poetry dedicated to her Hindu mentors and one to Maurycy Frydman, a Jewish Pole and a fellow theosophist whose Indian name was Bharatananda, and with whom she collaborated publishing the Polish-Indian Library for which she published books in Hindi, Tamil and English. Working with the Hindu poet Harischandra she worked on translation of Polish literature and poetry ranging from Kochanowski to the clandestine poetry of the Polish Underground in WWII.

She then launched her Indo-Polish Library with Peter Jordan’s book, “First to Fight.” In 1946, she co-authored “All for Freedom – the Warsaw Epic.” Her major work was, undoubtedly, the six-volume “Indian Anthology,” that included a volume titled Sanskrit, and in another one of her favorites, Kahlil Gibran’s Jesus.

Along with these literary undertakings she also wrote extensively for newspapers about the social conditions and the situation of the rural population, about the importance of instilling in children a love of their country, and about the tragic situation in Poland. To identify with the Indian population, she chose to travel third class on trains, something not done by white people.

Not surprisingly, her strong belief in the dignity of all people demanded acts, and not just words. She threw herself into helping the Polish refugees arriving in India during the war, not just by writing for the press but also involving herself in their lives. She especially wanted to ensure the children would learn something about their host country, arranging for some of the older ones entrance to Indian schools, engaging with the Scouts, and even took on the role of “impresario,” organizing a 3,000 kilometre tour for a fortunate few, financed by their public performances along the way. The trip was the subject of an article in the newspaper, Misindia, in Bangalore in which the young Poles were praised for their dancing which was compared to some dances of southern India, Kumni and Kilattem. It was said the Polish youth was there to learn about India and in turn to introduce something of Poland to the Indians they met, a dialogue between peoples so important to Umadevi.

Is it any surprise, then, that she was also a passionate supporter of Gandhi’s independence movement? In a collective memoir, a few Polish girls recalled carrying letters between Umadevi and Gandhi, no doubt to circumvent the censors. But this was a non-violent movement and one she could heartily support. It was an unforgettable experience for those who met the great man, one they considered the “father” of his country.

When Gandhi came to speak to a group of Polish youth, he expressed his sympathy for the terrible suffering that has been inflicted on their country and told them he prays for Poland. He told the young people that they must study and prepare to go back and help Poland be strong again. He also told them that they must forgive, for their own sake as well as for others. They must have courage, but this courage is to be directed to peaceful enterprises; violence will not gain them anything. He quoted from Christ’s teachings. The Polish youth expressed surprise that he knew this to which he replied that there is great wisdom in all the great religions; that is why he studied them and he respects them all highly. At a large public gathering, he said, “Never belittle another’s faith but instead encourage him to follow its teaching faithfully.”

Years later, Umadevi was once again passionately supporting another wave of refugees, this time the Tibetans escaping from Chinese occupation of their country. She worked tirelessly, feeding them, dressing wounds, making clothes. She founded schools, introducing the Montessori method in early education, placed some older students in schools throughout India, and was instrumental in obtaining scholarships for many students to study in Switzerland. She spent a lot of time with the Dalai Lama and others in his circle, and published works on Mahayana Buddhism and other aspects of Tibetan culture. She felt that her experience as a Pole growing up under Russian occupation gave her an insight into the importance of preserving one’s culture.

And yet, she felt she had failed to do enough for the Tibetans, and that revived memories of the Polish tragedy. In the 1960s she traveled twice to Poland, where she met with Bishop Karol Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II) and discussed with him the plight of the Tibetan people. While there, she meditated at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.

In her final year she was no longer able to live at high altitudes. She returned to live in a convent in Delhi where she was cared for by some Tibetan girls. When she died, she received last rites from a Polish Catholic priest, and her funeral rites were performed by Tibetan lamas, true to her belief that all religions are one, containing within them the essential truth.

CR

Sources:

1. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi: A Biographical Essay by Kazimierz Tokarski, translated by Anna Sowinska, Theosophical History: A Quarterly Journal of Research, Vol. V, No. 3, July 1994; Professor James A. Santucci, ed., Department of comparative Religion, University of California, Fullerton CA.

2. The collective memoir, Polacy w Indiach, 1942-1948, and the archives of the Sikorski Museum in London.

THEOSOPHICAL HISTORY

A Quarterly Journal of Research Founded by Leslie Price, 1985. Volume V, No. 3 July 1994.

A long-awaited article by Mr. Kazimierz Tokarski on the life of the Polish Theosophist, poet, and translator and publisher, Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi (1888–1971), is the major research article appearing in this issue. Practically unknown outside of Poland, Miss Dynowska-Umadevi was instrumental in establishing the Polish Theosophical Society and the Order of the Star in the East in Poland (known there as the Aurora Society), for translating Theosophical works and works by J. Krishnamurti into Polish, for being an established Polish poet, and above all for being a seeker of Truth and a humanitarian. Her interest in India and close association with M. Gandhi brought about a cross-fertilization of Indian and Polish cultures through friendship with the Indian poet Harischandra Bhatt (1901–1951): Dynowska-Umadevi establishing the Polish-Indian Library— publishing books in Hindi, Tamil, and English— and producing (under the sponsorship of the Indian Ministry of Education) her greatest work, the six-volume Indian Anthology; and Harischandra Bhatt as translator of works in Polish literature. She later wrote, “That bridge which I build with books between the souls of India and Poland is for the distant future. I do not know what its value and significance are…I will only get to know in the moment of my death, then I will see in a flash the very essence of my life, my Dharma and my mission.” Besides her literary work, Dynowska-Umadevi in her later life dis-played an inclination toward altruism that one cannot help but admire. Her work with Tibetan

refugees after the Chinese incursion in Tibet in 1960 extended throughout her later years until shortly before her death in 1971. During her lifetime she was greatly admired by her circle of friends and associates. Indeed, it was at the behest of her friends that the author, Kazimierz Tokarski, wrote this biographical essay out of respect and admiration for her. For her service to humanity, she deserves wider recognition. Mr. Tokarski therefore deserves our gratitude for introducing Miss Dynowska-Umadevi to the English-speaking world.

TH-V-3-Jul1994The Scarlet Muse, an anthology of Polish poems translated into English by Umadevi (Wanda Dynowska) and Harischandra Bhatt.

https://www.generallyaboutbooks.com/2015/12/the-scarlet-muse.html

Wanda Dynowska, Polish Yogini.

https://radza-joga.blogspot.com/p/umadevi-wanda-dynowska.html

The extraordinary fate of Wanda Dynowska and Michał Tokarzewski-Karaszkiewicz.

The Dalai Lama’s adoptive mother was Polish!

https://podroze.onet.pl/ciekawe/wanda-dynowska-umadevi-przybrana-matka-dalajlamy/c35cpqx