Extract from Saints Alive by Hilda Charlton

Hilda Charlton was a spiritual teacher who taught meditation in New York City from 1965 to 1988. In her teachings Hilda stressed the importance of a life of giving and forgiving, unconditional love and remembrance of God. She uplifted the lives of thousands of people who sought her spiritual guidance. She was born in London and moved to the United States along with her parents and two elder brothers when she was four years old. As a young student she learnt classical ballet dancing and from the age of eighteen for the next two decades she performed and taught dancing in the San Francisco area. But right from her childhood her real quest was spiritual. From 1947 to 1950, Hilda toured India and Ceylon as a dancer. After that she lived in India and Ceylon for fifteen more years, pursuing her studies of Eastern mysticism and meditation under the guidance of many great spiritual masters.

There are great gurus in this world, like Sathya Sai Baba. When he goes into a town, a hundred thousand , two hundred thousand people will be there to mob the place. They sing all night. I’ve been there. I’ve stayed at a place where the police had to come to keep calmness and quietness in the street. There are those beloved such as Satchitananda, who built the city of Yogaville with his inspiration; the great Anandamayi, who attracted thousands; the Yogi Bhajans, the Muktanandas that attract so many. Perhaps many of you belong to them. But there are some other yogis that some of you might not know much about, They are not even yogis – they are beyond yogis. They are simple, quiet people who are hidden and not known, who stay incognito, who act like beggars, who act foolishly so you won’t know they are anything special. They might throw rocks when people come near, like Nityananda did at one time so they would think he was insane. They are people who just hide.

Hidden angels and hidden divinities – It’s hard to find them. I’ll tell you later what I think their work is.

I’m going to call on Will to speak. He’s going to talk of a great hidden one he knows who lives near where Ramana Maharshi was. Some of you may know this hidden one, and others of you may not understand; may be you passed him and thought, “What a old beggar”. I found him, though I have not yet met him on the physical plane. I received a letter from him and I saw through his disguise. I’m not teaching you about another guru tonight. He’s not a guru. He wouldn’t have you. His work is universal. No, I’m not teaching another teacher – I’m teaching a way. You see, kids, it’s very nice to sit here and have Hilda make you laugh or something, but what if Hilda went at you? What if Hilda demanded certain things, as I do of some of the people around me? It’s a tough scene, I’m telling you, to be in the presence of someone like that. They demand something, or get out!

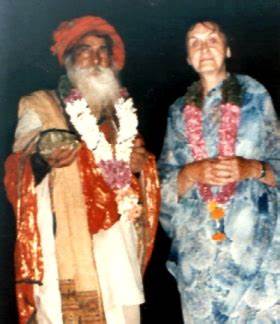

Now, Will, you tell us exactly your experience of this great one. Yogi Ramsuratkumar is this great one’s name. He looks like a beggar. He carries a crazy spear, he is in rags, he doesn’t bathe and yet smells like roses, and look what he has made of himself.

Will: “He usually changes his clothes about once a year. He’s a very, very eccentric being, to say the very least. He dresses as a beggar, he comes on as a beggar. He doesn’t have polish on the outside, except that his eyes and his face are just totally marvellous, totally unbelievable. The guy walks like he’s walking on two inches of air, as Hilda was teaching us to do tonight. And he goes very, very quickly, like a locomotive, so rapidly that Joan, my wife, and I had a very hard time keeping up with him physically – and we think that we walk very fast. He would just shoot off in one direction, and it would be very difficult to follow.

He’s a very incredible, beautiful person. He lives in Tiruvannamalai. There’s a set of brass shops near the temple, and every night at eight o’clock or so, they all shut down. He sleeps there in the night, and then in the morning he gets up and usually goes out near the railway station. He sits under a very, very small tree, and he does his work.

“He’s unknown to the world, and most of the people around there think he’s just totally nuts. He walks around. He sings. He has this big staff. It looks like a bow and arrow with peacock feathers. He finds strings and ties everything, everything, on the strings. He just carries that around, holds it and sometimes he’ll say, ‘Sita Ram, Ram Rain Sita Ram, Jai Jai Sita Ram.’ The kids love him. They all come out to be near him, and he says that within three days he can have any kid be his best friend. I’ve seen it. They come out and they say, ‘Ram! Ram!, He says ‘Govinda Ram!’ Within a few days of this, even the little Muslim kids say, ‘Ram! Ram!’ too. And their parents look at them very strangely.

“Anyway, Yogi Ramsuratkumar is a total child, and that’s the major thing. I don’t know what his physical age is – he may be about sixty. But he’s just a kid, just a really joyous, joyous kid at heart. I’ve seen him get up in the middle of the night and sing ‘Rama Rama’ and dance in ecstasy. And then sit down again, within the total bliss of it all. When he sings, he sings with his whole being.

“I’ll relate to you when I first met him. We heard a lot about him from our friend Caylor. Yogi Ramsuratkumar apparently knew us. He had told Caylor some information about our natures and what we were to do in this life. He already knew. When Caylor took us to see him, he was under a small shrub bush, a very small pine. It was very hot. He would always keep us in the shade by moving us around. When we met him, he was very, very thankful. We had done something which he considered a favour, so he very, very sweetly told us how much he was indebted to us. And we said ‘No, no. It is our pleasure to serve you.’ Then he looked at me for a while, and he put his hand up. I was sitting may be two or three feet away. And he just put me into a really, really deep ecstasy. I closed my eyes and I saw light coming out of my head, and I was way out of my body consciousness within about a minute. And then he said, ‘Mr. Will, Mr. Will don’t go that side, come back, come this side.’ And I couldn’t come down, I just couldn’t.

“Then he said, ‘Ohhh, not so good to go that side. ‘He said, ‘No good cigarettes on that side.”

Hilda : Understand, kids, that Yogi Ramsuratkumar smokes because his teacher told him to smoke to stay down, like Shirdi Sai Baba did, like Ramakrishna did.

Will : “And then he said a very strange thing. He repeated four numbers. He said, ‘Two, nine, zero, eight.’ And immediately I was back in my body, just instantly, and I had my eyes open. He said, ‘Oh-ho, so that’s your number.’ He wrote it down on a piece of paper, circled it and gave it to me. I was trying to get the meaning out of him. I said, ‘Swami, what is this number? Is this my room number in heaven?’ He just cracked up all over the place. He said, ‘Oh, no. Oh, this sinner just did something in his madness. He doesn’t know what he did.’

“He always refers to himself as ‘this beggar, this madman’. ‘He never uses the first person. I think maybe once during our stay of eight months did I hear the word ‘I’. It was a very, very special night, Shiva Ratri or something like that.

“Once there were people really hassling him. Politically he wasn’t very well liked because he was advocating the unity of India, and at this time this particular state had advocated secession from India, and the local government was not very sympathetic to Indira Gandhi or the central government. Yogi Ramsuratkumar said, ‘India must be united. India must be whole. It must be, to do its work on the Earth.’ They were really hassling him one day, and it was a very, very gruelling day, and I said, ‘Swami, why do you take this? Why do you do this?’ And he said, ‘This beggar’s here not to defend his ego. He’s only here to do the Father’s work.’ And that’s really a lesson for me, because we all feel what we do is right and we push ourselves and we force ourselves – and he merely said he’s not here to defend his ego.

“He does work in very strange ways. Sometimes we would order tea. He would have somebody to go out and get the tea, or Joan or I would go get the tea. But sometimes he would serve the tea himself. You would think it wouldn’t be any big deal just to serve the tea. But when he served tea, he would place the cups exactly. If there were five of us, he would serve one here, and then go over and serve another one there – in no seeming order whatsoever. Once I made the mistake of moving my cup a little, and he just stopped and said, ‘This beggar put that cup there for a purpose, and he knew just what he was doing.’ Then he walked around and walked around and held his beard like this, and just walked around with this very, very, very determined look on his face. He walked around and held his staff up and walked around some more, and then finally he came back. And then, after the tea was about cold, he served it. And he said, ‘Well, this beggar did what he could.’ After that I never ever did that again, and I really followed his instructions to the letter because he was just too severe when I didn’t.

“To be put down like that once, I tell you – I never wanted it to happen again. It’s very, very, very severe, his tone of voice, his whole look at you – it’s something that bums through you. You just can’t face it. Once I said something, and he thought I shouldn’t have said it. I was going to defend myself, and he just put his hand up to stop me. And I stopped right there. So he went at it for a while, and then finally in my mind I just let it go, and he stopped. He was very, very severe. Whenever you did something that wasn’t conscious, that wasn’t in harmony with his work, he would really make you regret it. You would feel so bad, and yet you couldn’t do anything about it. But that’s the way you learn, unfortunately – or that’s the way some of us learn.

“In the morning after we got up, we usually went and spent the afternoon or the evening with him, but then he would send us away at night. Once we had the grace to spend two full weeks, night and day, twenty-four hours a day, with him. I think I went home once; I was out of his sight for an hour. It was really intense, and I really learned a lot. But I also went through a few trips about it.

“For his bath he carries a coconut bowl, just a little shell of a coconut, cleaned out and dried. That’s his water pail, so to speak. He drinks out of it, he eats out of it, he washes with it. He fills it full of water, then splashes it over his face, throws a little over his head, and the guy looks like he’s just had a bath that cost a million dollars. He is just so radiantly beautiful.

“Then he assigns everybody to carry something. He always had big bundles of newspaper all tied up in burlap bags. Sometimes there would be four huge bags. He would never throw them away, and he would just carry them around. He usually had two Indian devotees there. They were very, very well disciplined, and very sweet people. Once when he assigned me to carry some thing, I made the mistake of saying, ‘Swami, i don’t want to carry that. Let me carry this.’ No. You did only exactly what he said. Sometimes he would have you carry nothing, and it would be seemingly unfair because somebody else would have such a tremendous load, and you would be walking around with nothing, feeling like a real fool. But he would say, ‘It doesn’t matter. You’re doing something else for me.’

“Once we were walking down to go out to this field where we usually went. In South India there are a lot of rice paddies with little dams between them, and those very thin dams are the paths you walk on so that you don’t spoil the crops. We are walking with him, carrying our big burdens early in the morning, by the beautiful holy mountain Arunachala. We weren’t being so observant – we were so enamoured with the beauty of the mountains, the beauty of the fresh air, the beauty of the crows and all the birds and everything. He stopped dead on the path, and Joan was in front and she hit right into him, and I hit into her. It was like the Marx Brothers. He really gave it to us for that. He said, ‘This beggar doesn’t want you to think about any mantras. Don’t think of any gurus. Don’t even think of God. Be observant and do what he says to do.’ He said, ‘We have this work to do nicely and that’s all you have to be concerned with.’ We really learned to be aware after that.

“He would use the staff in a very nice way. We might be going down the street, and he would put his staff up and say, ‘Stop. Go over to the side.’ And just that second a car would turn around the comer. His political enemies had tried to run him over about three or four times, so he was a little conscious about that. They had knifed him a few times, too. Once they knifed him and he just rubbed his hand over the wound, saying, ‘Rama, Rama, Rama’ and it was healed.

“He used to place little things around Tiruvannamalai. He would smoke a pack of cigarettes and then throw down the wrapper. Then just before we left, maybe about three or four hours later, he would pick the wrapper up again and put it in his pocket. His pockets were just bulging with all kinds of things, every little thing imaginable. He never threw out anything. Even his old clothes were in the sack he carried. And then he would place little things around Tiruvannamalai. He would look for the exact place, the exact time to put something, and then he would put it there, and a few days later he would come back and get it. It would be right there, and he would put it in his pocket again. He never threw anything out.

“Once he had this little sack tied up in his clothes. I said, ‘What’s in this little sack?’ He took it out, and it was some nellika, which is like a very salty little nut. Then he said, ‘Oh, I didn’t know I had these’. He made us eat them and they were very, very sour. And he said,” Oh, these are so good for you, really so good for you.’ So we really had to be on our toes.

“His awareness was really fantastic. Once a girl from Canada came to see him. She was sitting op- posite to him, and Joan and I were sitting on the side, facing another direction. It was about midnight. In Tiruvannamalai they have a lot of owls, and in the distance, in the direction that Joan and I could see, a little owl came and perched on a very, very far roof. It was there for about a minute and flew off. And the very next thing he said to the girl was, ‘Tell me. Do you have owls in Canada?’ We were just astounded because we had been sitting there so quietly, and then we noticed the owl. He wasn’t even facing in the same direction that we were. He would have had to see it out of the far, far comer of his eye, and yet it seemed as if he were giving this girl all of his attention.

“Being with him was really a lot of fun. He used to make fun of himself constantly. He would call himself ‘this beggar, this madman.’ Caylor told us that once when he was with him, before he could say anything, Swami said, ‘Oh, you’re thinking this about this beggar and that about this beggar.’ He was dumbfounded because that’s exactly what he had been going to say. He just sat down, shut up and was very quiet for a while.”

Hilda : Thank you, Will. Joan, would you say something about Yogi Ramsuratkumar? Is this interesting to you, kids, to hear about a different kind of a yogi, hiding behind rags? I’ll tell you afterwards what I believe he does.

Joan : “I feel it’s such an honour just to get a chance to talk about Yogi Ramsuratkurnar. I can hardly believe this opportunity that’s been given to us. I know that the beggar in Tiruvannamalai would probably weep joyous tears at the thought of people in another part of world, so many hundreds of us, thinking about him and talking about him.

“Will told you about the teacups that were misplaced. My first experience with his sternness came one evening when the two devotees Will had spoken about had gone back to their homes because they had some work to do there. They weren’t able to stay overnight with him. As usual, we had come from the field into town and had settled ourselves on the stone platform, where we were talking. We had some tea together, and when the shops began to close, Swami said that it was time to move now, meaning that we should move all the things over to the place where he slept every night.

“This one particular night he was having to work with just Will and me, who were not very aware, although we’d been with him for some weeks. He said, ‘This beggar will try to do this nicely, but there may be some difficulty.’ So slowly we took those huge burlap bags filled with newspapers and no telling what else over to the spot where he slept. After we got ourselves moved over there, we just sat quietly and lit a candle because it was very dark. Everything was just so quiet, so peaceful. Then Swami said, ‘Joan!’ And I came to attention. He said, ‘You can do some work for this beggar,’ and I was thrilled. He said, ‘Pannal isn’t here. You can unroll my bed. ‘Well, his bed – one would never suspect it as it was only a roll of burlap rags – was stuffed away underneath the shelf that a shopkeeper had kindly let him use. He began to explain to me very carefully how I was to do this work. I was just so excited about the opportunity to do something like this for him, something more than carrying newspapers or whatever. Except I always especially liked to carry his staff. He told me in detail how I was to proceed about this work and said, ‘Don’t get up now. This beggar will explain how you must do this nicely.’ I sat there, all the time thinking in my mind that I knew how to roll out a bed, because we had sleeping bags and I knew how to unroll those. I waited patiently until he explained it all to me. And then he said, ‘Now you can do this’. So I got up and went over to the burlap bag and began to unroll it according to my own idea. He jumped up and said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘Well, Swami, I’m..uh..you know..’ And he said, ‘Sit down.’ I was just mortified. I said, ‘Swami,’ trying to continue, but again lie said, ‘Sit down.’ So I sat down. I tried to defend myself by telling myself that lie hadn’t spoken clearly. Of course, the truth was that I hadn’t heard what he was telling me. Then after some minutes of silence which felt like hours to me, he said, ‘Mr. Will, Joan thinks this beggar is very arrogant.’ I was shocked because I’m sure I was thinking he was very arrogant. And then he became very serious once more, and he explained so I understood. He said, ‘After sometime, when you’ve been with this beggar, sometimes he treats you differently.’ He explained that, and for the first time I realized that if we were going to stay there with him, I was going to have to really listen and follow the instructions he was giving me, because these instructions, though they didn’t seem very important, were really, really important. Hilda has enlightened us even more about the meanings behind them.

“Once when we were in the field, sitting under the tree that Will spoke of, we had the honour of helping him write a letter to a man who had been to see Yogi Ramsuratkumar and was a devotee of Sathya Sai Baba. He had since gone back to Europe. Swami said, ‘I must write to Sri Raman today. ‘Any casual observer would think, here’s this mad fellow, this beggar, just sitting under a tree, and he should have plenty of time for everything. But his work was so intense. Can you imagine that he only changed clothes may be once in six months? I remember once he had on a new set of clothes and he looked glorious. But he said, ‘This beggar, this sinner, had no chance to get a bath.’ There just wasn’t time for him to spend on himself to take a bath.

“So he began to write a letter to Sri Raman, and we were speaking about the things that Sri Raman had written to him and what things Swami wanted to tell him. The letter was written nicely. Then it got to be about five o’clock and we heard the evening whistle, so he said we should be going and told me to take care of the letter. ‘Here, hold this letter, and carry it,’ he said to me very firmly. ‘Just hold it and carry it.’ But I began to think on my own that if we walked along the dirt road, the path that we usually followed, I would probably have it spoiled by the time we had to mail it. So I said, ‘Swami, I have a good idea.’ He didn’t like my saying this, but he was very nice. He said, ‘Yes, what is it?’ I said, ‘Swami, why don’t we put the letter between the newspapers and I’ll carry it in the newspapers. Then when we get to the post office, it’ll be in perfect condition.’ He mumbled. ‘This beggar thought it would be better if you hold it, but all right, do it your way.’ So I thought, ‘Oh, boy, it’s going to be in perfect condition.’ I put it in the newspapers and thought no more about it. I got to carry a few more things also, and we stopped to sit on a rock near a farmhouse where he was known to the people who lived there. Parmal, his devotee, was alerted that he would be taking the letter to Sri Raman to mail at the post office. Swami said, ‘Joan, give me the letter.’ I opened up the newspapers, but by some horrible accident the letter had slipped down the newspapers, and my hand – it was hot weather, you know – had spoiled the edge. It was torn. That was the first thing he saw, the tear in the letter. It was just horrible. To make matters worse, the two men who were with him all the time were laughing! Swami said, ‘This beggar will do what lie can, but it won’t be the same. He’ll do what lie can. He’ll make some lines on the letter, but it won’t be the same.”

Hilda : Thanks, Joan. Caylor, speak just for a second or two. Loud and clear.

Caylor : “I went to India in the spring of 1970. For about six years I knew him and frequently went to see him. He’s a fantastic being, and the longer I’m away from him, the more I feel this in my heart. I’ll tell you the way we met, the beginning of it all.”

“At that time he had lived in Tiruvannamalai for about thirteen years. No one knew him except for just the few village people who understood who he was. He avoided people. He walked for miles on the highways in a state of trance. He would sit in graveyards for days and days and not eat, just to avoid people so he could be doing his work.

At this time I was eager to do some meditation in India to really profit from my stay there. I was like so many of the devotees of Ramana Maharshi who sat in the meditation room for five or six hours at different times of the day, However, I started to have tremendous pressure in my forehead. It would move up to the top of my head and my head would feel as if it were being pressed in a vise. I couldn’t stand it. I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t sit still, and I couldn’t think. Nothing seemed to stop it. I went from one person in the ashram to another, but no one seemed to be able to help me, no one. I was astonished that there wasn’t someone there who could do that work or understand it.

“So finally I went to an old French woman in the ashram who’d been in Tiruvannamalai for about seven years. She knew one person, she said. But oh, no, I’d never find him – she couldn’t even find him. I asked her again the next day when she was walking on the hill at sunset, and she said, ‘All right, I’l1 watch for him tomorrow when I go to the bazar.’ The next day she went and she saw him there. You know, it was as if he were waiting for her, because otherwise she never would have round him. He told her to bring me to the temple at five o’clock the next evening.

“So there I am waiting at five minutes before five, and here he comes, with about a half dozen little kids all prancing around him. He’s just ecstatic, he’s just floating, and the kids are all dancing, and they’re so happy together. Finally we sit down, and he gives me some flowers, and I give him the flowers I have. He asks me some questions about where I’m from and so on. I tell him about my problem, and he tells me to come back alone the next day to the bazaar, to a little stone-carving shop where they make tiny little deities. The next day there he tells me to sit still and not to think about anything. He puts his hand on my head, and for the first time in months, suddenly this whole pressure just disappears; it’s gone. He explains that it’s probably going to come back in two weeks and that if it does, I should find him again. How? You know, it didn’t occur to me that I’d have to find him, that I’d have to really hunt.

“So in two weeks the pressure came back. I prayed and I prayed that I’d be able to find him, and I designated that he would be under the main archway into the temple, where I had left him two weeks earlier. That evening I started off early, and it was storming by the time I got there. There are thousands of people selling things on the streets of India, and every one of them was stuffed under that archway. It was just incredible. How was I to find him? He would never be there with so many people – and be wasn’t. So I ran out into the street and I ran here and I ran there. I looked in tea shops, I looked everywhere – I was desperate. Finally, alter about half an hour, I ran out into the street, turned around and there he stood, inches from my nose. He jumped away and said, ‘Mr. Caylor, what are you doing here?’ And I said, ‘Oh Swami!’ and I grabbed him and hugged him. He took me to the tea shop where we sat and talked about American Indians for about half an hour, just to get my mind off my problems. Then he put his hand on my head again, and it went away. And I’ve never had that problem since. But that’s how it all began.

“And then began a long process of learning things like Will and Joan have told you. I learned how every single thing he touches – even if it’s a cigarette butt or the package or a twig he plays with or a string that he’s taken off a little wrapper of food – anything he’s ever touched you can’t just throw away, because there’s power in there. There’s something: there’s an essence, there’s a quality. It may be months before he finds time to empty his pockets and place everything where it will do some work. It takes a long time to see him doing these things. He doesn’t talk about them. He’s a beggar. He calls all these things his ‘madness.’ He loves to talk about how bizarre he is . It’s really remarkable.

“You have to learn little things – like when he’s talking, you can’t interrupt. It took me time after time of interrupting to learn this. After hours of sitting with him, he would be in a sort of abstracted state, and he’d have me talk about a particular subject. It was always different, but always specific. For a half hour, an hour, an hour and a half, he would ask me questions, and I would keep going. After the day had gone by, my head would be so tight that I couldn’t take any more from him. I’d have to go out and be away for a while. But as this was going on, if I tried to change the subject, suddenly he’d stop and say, ‘We’ll talk about that later.’ He’d ask me another question. He explained once, and I finally understood, that to stop him and to change the subject was like derailing a train going at sixty or ninety miles an hour. He’s intensely involved in a certain work. And to suddenly change the subject is to leave all that up in the air. You know how we feel when we’re working and somebody interrupts us. But he works on so many different levels all at one time that to just simply change the subject – what does it do to that man? It’s astonishing.

“When we walked with him or when we sat with him, he was always so conscious of where every one was. We all had to be in a certain arrangement. He’d think a long time about where he would put us before we would even get to sit down. And if I let somebody walk between us while we were walking in the bazaar, it would upset him. It upset his body physically. He would remind me, ‘Please don’t allow anyone to break us up.’ We would have been working together for days, hours, on whatever it was.

“He talked about himself a little bit. One very beautiful story is that one morning, as usual, he was going to a little shop in the bazaar where he bought cigarettes – but maybe be went at that time knowing who was going to be there. He saw an old sadhu also buying something, maybe some cigarettes too. And this sadhu takes from the shop owner what he had asked for and turns around and looks at Swami and says, ‘Who are you?’ Swami takes a step back, and he looks at him as he does out of the comer of his eye, and he says, ‘I am who you are. And who are you?’ It was this joyous occasion of two Masters meeting, and they both knew it was this little leela, this little miracle, right in the bazaar. They embraced.

“I’ve written some things about him, beautiful things I think, and he used to love to have me read them over and over and over. He would say, ‘You know, this beggar is only the dust at the Lord’s feet. And you have taken this soil and you have made it into some mud. That’s all I am, this beggar’s just mud. And you have shaped it and fashioned it like a master crafts man into some beautiful, beautiful statue. He would say, I can’t ever thank you for what you’ve made of this beggar.’ To hear him talk like this – well, I don’t know what to say.

Once or twice late at night he has said to me that he is a Master. And he has said something very beautiful which I always remember. He said, ‘I am infinite and so are you and so is everyone, my friend. You see only a small part of the real man, like a man standing on the seashore of a great ocean and looking out, sees only a small portion of that great ocean. Like that, you see only an infinitesimal part of me.’ And he said, ‘I am Infinite.’

Hilda : Thank you very much. Thank you.

What I wanted to say was that to me, those who work like that are working with the Infinite . Do you comprehend what he was doing, kids, when he put a teacup here and one over here and one over here and one over here and nobody could move them? He was working with the Infinite. Do you understand? Do you comprehend at all? He was placing something that had power to change the world. He might have been working with religions. He might have been working with countries. He might have been working with ideas. But he was shaping things. And he once said to Joan, “Watch this world in twenty-five years.” What did he say, Joan?

Joan: “He said if we were to just stop our existence now and wake up again in twenty-five years, the glorious world that we would see in twenty-five years we wouldn’t even recognize. We wouldn’t believe that it was the same world we had once been in.

Hilda: See, do you understand what he was doing? What these silent ones, these people who are never known to you, do? They don’t have big crowds, they don’t have Yogavilles. I’m not downing any of that, kids. I’m not downing the hundreds of thousands following well-known yogis. I’m not downing any of it. But there are the invisible ones at work, and I’ve always said it’s these people along with the other great ones who keep the world in balance.

He takes a stone and puts it here. He has a reason. He puts a thought behind it. And he hides behind his craziness; he hides behind his laughter. But he’s stem, stem, so stem you have to do it just right. And people don’t understand – why can’t you just do it sloppy?

Why not? Because when he puts a stone there, he’s placing it for the universe; he’s placing it for the world. He’s changing the world with his thoughts, with his power. I tell you, I’ve had a letter from that man, and he calls himself with every other word, “this old sinner, this old beggar.” Well, if he’s a sinner and beggar, he’s the most beautiful ‘sinner and beggar in this universe. He’s powerful! If he puts a stone down, he changes the world!.

He reminds me somewhat of Shirdi Sai Baba, who would go out on the temple porch in the afternoon and nobody would go near him because he was doing his universal things. They aren’t funny, these strange people.

These hidden angels, these great ones, help hold the world in balance. Perhaps they appear mystical to some, foolish to others, insane in the minds of the earthly sick ones who are tied to customs. Oh, we have a custom, you mustn’t wear rags, no, no. Mustn’t tie pieces of rock in your clothes. You’ll end up in Bellevue with a psychiatrist saying you mustn’t tie rocks in you dress. That’s not nice, that’s not the way humans do things. You’ve got to do it just the way everybody else does. Well, these great ones don’t. Their ways break the rules of cultures. But to me they are the sacred ones who sacredly work for their brothers and sisters unnoticed – except that I brought it out into the open here, with all my heart. And he knows it this night. He knows it. I’m going to write him and tell him that people in the second biggest cathedral hall on the Earth heard all about you, Swami.

To these hidden brothers and sisters of light, let us humbly bow. They care not for fame, for recognition, but quietly walk through life as God’s beacons of truth and light. And I sang out from my soul with them as I awakened this morning, and I heard these words. They were wonderful as I awakened. “I love life'” I said, in all its diversities. I love giving, I love receiving, I love the sun, I love the moon, I love the mud. I love the hardships. And I love the glory. Yes, I love life, God’s life in all its diversities and forms. And best of all, I love the Formless One.”

Yes, these hidden ones, kids, these hidden ones work that way. Let me know that there are a few hundred here that understand things beyond their ken, beyond their mind. I had a hard day today, but I came here laughing, laughing like a fool. New people will say, “What is that crazy woman up there laughing about?”

Nope, the hidden ones like Yogi Ramsuratkumar are not crazy. He knows just what he’s doing for the universe – and he’s changing the universe. I know when I work in the funny way that I work – if 1 never saw you kids again and never left my room, I’d still be working for the universal as I do with the Master Pericles. Watch the papers for the results of the work we here are doing for Greece, for Egypt and for Israel. I have somebody else watch the papers. I don’t read them. I’m not like the great ones carrying newspapers. Now do we know what he’s got in those newspapers? Maybe he is carrying the world in those newspapers! Do you understand? And we say he’s nuts.

Well, I’m telling you, let’s change our ideas of right and wrong this night, shall we? Let’s get up out of our strait-jackets. Let’s change those ideas of what’s right and wrong this moment and know that some- where in India or in the mountains here are great ones – hidden – never seen by you or me, perhaps, but who are keeping our world in balance.

Hilda Charlton – a tribute

Hilda Charlton was a spiritual teacher who taught meditation in New York City from 1965 to 1988. In her teachings Hilda stressed the importance of a life of giving and forgiving, unconditional love and remembrance of God. She uplifted the lives of thousands of people who sought her spiritual guidance. She was born in London and moved to United States along with her parents and two elder brothers when she was four years old. As a young student she learnt classical ballet dancing and from the age of eighteen for the next two decades she performed and taught dancing in the San Francisco area. But right from her childhood her real quest was spiritual. From 1947 to 1950, Hilda toured India and Ceylon as a dancer. After that she lived in India and Ceylon for fifteen more years, pursuing her studies of Eastern mysticism and meditation under the guidance of many great spiritual masters.

This story of Hilda is based on her autobiography, Hell bent for Heaven. All phrases and sentences in quotes are Hilda’s own words unless otherwise mentioned.

Hilda was direct, simple and filled with life1. The then president of Gold Mountain Entertainment, Danny Goldberg said of Hilda, “When Hilda talked about saints, she began with a gushing enthusiasm I would normally associate with a teenage girl contemplating her latest heartthrob. Almost imperceptibly her tone altered from one of girlishness to a solemnity manifesting the holiness of the saints’ lives to the jocular familiarity of a next door neighbour. Only gradually, subtly, and with the utmost concentration did it dawn on me that she herself was one of them.”

When Hilda was six weeks old, D.W. Foote, a dynamic orator and leader of the Truth Seekers Society, an organization of agnostics, dedicated her to “truth, goodness and freedom for all mankind” in front of a large audience at Albert Hall. Hilda’s parents wanted to name her Harriet Martineau, after the great feminist writer. But in those days “Harriet” was used extensively in London by the costermongers, fruit and vegetable hawkers who pronounced it “‘arriet,” without the H. So her parents after much discussion settled for second-best “Hilda.” (Interestingly many years later when Hilda was in India she visited the Brighu Rishi Sastri Center in the small village of Hoshiarpur in northern India. At this center where kept the ancient horoscopes that were written by sage Brighu Rishi thousands of years ago and contain detailed events of every human being’s life. After looking through hundreds of pieces of parchment, Hilda found her name. There it was, spelled out: Hilda Charlton and not “Harriet”.)

Hilda’s father, Ernest Arthur Charlton was an idealist. He had an artistic temperament and was an aspiring songwriter who had already published a few songs. Though an agnostic he believed in the fundamental goodness of man. Once as a little child when Hilda asked him what her religion was he quietly said, “To do good is your religion.” Arthur did not want his sons (Hilda’s two older brothers) to grow up in a country like England where they might have to go to war (this was around 1905 before World War I). So when Hilda was four years old the whole family sailed for the new land, America. Being an agnostic Hilda’s father did not believe in the hereafter. He would say, “The only hereafter is that I will become part of nature again and come up as grass.” But Hilda said, “What a surprise Dad had when many years later he passed on at the age of fifty-seven and found that he still lived.” Few days after he passed away, one night when Hilda was in her room she saw a light and her father appeared as if looking through the light. “He looked about twenty three, was vitally alive and enthusiastic with the continuity of life.” He told her that he was doing all the things he wanted to do — painting, writing, composing music. He also said he was looking after Mother. Hilda observed, “A peace filled the room as the light faded and with it the vision of my father.”

Even as a four year old, Hilda was a very strong willed person. She was a born vegetarian and no body could budge her from her chosen diet. This caused much discord in her family as vegetarianism was not so prevalent in those days. Her mother would sternly say, “Eat that egg or sit there.” Hilda would sit there until, in a voice filled with desperation, her mother would release her with, “Oh, get up!”. From her early days Hilda had great faith in the goodness of life. Every morning when she woke up she would lift up her pillow and look for chocolate candies. As she later explained, “Every morning I was amazed that there were none under the pillow — amazed, not disgruntled. But I would look again the next morning. I was never daunted by the lack of them. There was always a tomorrow.” From the age of seven Hilda had an insatiable desire, burning within like fire, for perfection. Later in life, a friend called it being “hell-bent for heaven.” So one hot summer day as the seven year old Hilda was walking beside her mother holding her hand, she felt close and intimate with her mother and confided her inner feelings to her, “I am perfect, except my ears stick out.” On hearing this, her mother casually remarked, “We will get your ears fixed.” But when she announced the same news of her perfection to the school, the news was not accepted the way her mother had taken it. As Hilda observed, “In fact, it had a cataclysmic effect. The school kids chased me, surrounded me, yelled at me, “Yeah! Yeah! She’s perfect! She’s perfect! Let’s see your ears, come on, show your ears!”” Till then Hilda had only seen a few explosions but now she “felt the full impact of life”.

Like all kids of her age Hilda was also a sweet little kid full of fun and frolic — “kick-the-can, hide-and-seek, free movies in the Park in the summer, sleigh riding, ice skating on the lake in the park in winter”. But she was also “developing some strong quirks. Things were happening inside.” Multi-colored swirling rays of light were revolving inside her. She’d run to her Mother yelling, “Those lights, those lights!” and her mother would calmly say, “What lights?” That would end the subject and little Hilda would be “left worrying when they would appear again”. (Much later when she was into yoga did she realize that those ‘swirling rays of light’ were connected with the opening of the spiritual nerve centers, or chakras, within the body. At that time her agnostic family had never heard of chakras.) It was during this time that she was once playing the part of Joan of Arc in a play. During the performance she “saw a luminous white light, like a wide ribbon, shine down from the sky, and heard a voice. It said, “Je suis Jeanne d’Arc.” (I am Joan of Arc.)” The ray of light entered her. This experience had a phenomenal effect on her. According to Hilda till then she was a “weak worry-worm”. Now she became “a tiger cub”. She said, “One glance from me and that mean little neighbor boy would run as if I had a shotgun; the boy from whom I used to cringe ran like a coward behind his house.(This boy would often frighten Hilda by making faces at her.) I was amazed at the power I had… Fear had left… I was indomitable.”

When Hilda and her family came to America, they first stayed for ten years at Salt Lake City, Utah and then moved to Los Angeles, California. As a child Hilda had dreams in which she saw in vivid technicolor of herself dancing. At that time she had never seen dancing or even heard of dancing. When she was in junior high school her elder brother asked her to take up learning ballet dancing and he would pay for her lessons. He felt this would help her over come her awkward movements. In her childhood dreams she had seen herself leaping twenty feet in the air, floating and twirling on the tips of her toes. “Glorious! Divine!” But when she started to take the dancing lessons she realized it was not exactly “as the technicolor visions had shown.” It took her “some time to take an interest and for some understanding to click within” her. But once this happened she went “at it hook-line-and-sinker, an all-out job”. Hilda wrote, “I was in love: I had a love affair with Terpsichore, the Muse of Dance. It was my one and only love, until I heard about God years later…No one liked being in class with me. My goal was to leap higher, kick higher than anyone else, and I did. Plie, eschape, arabesque, pas-de-chat became my vocabulary. Biographies of Pavlova, Ruth St. Denis, Isadora Duncan, stories of Martha Graham, Nijinsky became my life. My leg was forever up on a chair or table, stretching… Life revolved around dance. Life had taken on a real meaning. I had a direction.” Much later it was dancing that took her to “the land of my heart — India” as she put it.

After graduating from high school in California, Hilda came back to Salt Lake City, Utah to study at a University. But she was not really into academics and a career. She did not finish her university studies. After a year or so she went back to Berkeley, California at the request of her father. She took up teaching dancing and taking lessons with a French dancing teacher. It was during this time, when she was living with two of her friends Wilma and Thelma in Compton, California, an incident happened that had a profound affect on the rest of her life. One evening they started playing a game where in one person would go out of the room, and those remaining would choose an object. The one would come back in and try to identify the object by going around the room and pointing to this and that. To every ones’ amazement, Hilda could walk right into the room and go to the object instantly. They played this game the whole evening. This had a disastrous effect on Hilda. As she later explained, “That which my soul had kept in abeyance while I grew up, my inner self of twirling lights I had known at four, was suddenly opened. Next day I could not cope with the world. I had opened up the psychic too soon; it was as if a veil had been ripped away, baring my inner self.” After this incident she returned home “to a time of great inner disturbance. The easy-going Hilda was no more. This was to be a time of trial and error.”

Soon after this incident Hilda’s father passed away. Hilda was still having a rough time getting herself in order. Finally it was a psychiatrist in San Francisco who found the cause of her stress. He told her that her breathing was too shallow and taught her to breathe deep from her abdomen. Hilda writes, “The psychic, opening so fast, had left me unable to cope with the body changes. The deep breathing was just the thing needed, for it was a preparation for the new life.” As she continued the deep breathing exercises she started feeling better and better. It was during this time she says God formally introduced himself to her. After Hilda’s father passed away her mother secretly started attending classes on the Bhagavad-Gita (Secretly because they were still supposed to be agnostics). Soon Hilda found out her mother’s hidden life. A few days later her mother told her that she was going to have a class at their home and that a teacher from the Orient would be present. Hilda’s mother also told her she could attend if she liked. Hilda chose to attend. She was in the seventh heaven of delight. Later reflecting on her spiritual beginnings she wrote, “Life started, the life for which I had come to Earth: truth — freedom — liberation — God. My heart still jumps with joy at the remembrance of those days, days of struggle, days of striving, sleepless nights of meditation…”

The spiritual meeting at Hilda’s home was attended by the yogi, Sri Daya, from India. From the very first meeting Daya took special interest in Hilda and for the next three months put her through intense training. Hilda had complete faith in him. She thought that God was speaking through him and that he was the world teacher. For Hilda he was the law. She said, “If he said, “Stand still,” I stood. If he said, “Talk,” I talked. If he said, “Meditate,” I did… Daya was stern, relentless and dictatorial… He taught me discipline, emotional control and control of the tongue.”

At the very first meeting Daya commanded Hilda to sit on the floor and cross her legs. In fact it seems he unceremoniously pulled her legs over each other in a yoga lotus position and told her not to move till he gave her permission. Hilda kept sitting in that position for two hours. “The pain was excruciating.” Then he turned to her and asked if she was willing to give one hour a day for peace? Deep within Hilda felt she was about to make a very important decision in her life and she answered, “Yes, I will.” According to her, the moment she answered in the affirmative, a surge of energy went through her. She said, “It was not the hour I had pledged, but a way of thinking, a way of life.”

On Daya’s recommendation Hilda started reading books on the lives of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda by Romaine Rolland. When she started to read Vivekananda’s life she said, “an explosion took place within me; it burst forth as a desire to serve… Vivekananda’s words touched something within, and feelings I had never experienced — new thoughts and new ways of looking at the same old world — were kindled within me… Vivekananda’s comments on The Mother (the Mother of the Universe) struck a harmonious chord within. I drifted into a natural state of contemplation. Ideas and understanding of what life was all about seemed to flow from a reservoir within… I wasn’t learning; I was re-remembering. ”

Daya used unorthodox methods to train Hilda in physical discipline and emotion control. Once he told her, “Learn mind control. Look at that nail on the wall and don’t let your mind wander.” Hilda “stared at the nail with utter faith”; she did not let her mind wander even for a moment for the next hour. At another time when Daya was giving a lecture to his devotees out in the open under the trees, Hilda for a moment let herself be distracted by a flower at her right side. She turned her head to look at it when she heard Daya say, “Hilda, where is your concentration? …Meditate in that position until I tell you to move.” Hilda wrote, “My neck, in that uncomfortable position, began to ache, and an hour went by and still he didn’t give the sign to move. Each minute became an eternity… I began to feel an inner strength welling up from within to help me retain the position. I heard Daya say, “You may move.” My neck was stuck and it was hard to get it back in place.” To teach emotional control he would make Hilda stand up in front of a room full of people attending his lecture. He would start saying all nasty things about her. He made things up. If Hilda allowed herself to shed even a single tear he would shout at her after the meeting, “You fool, why did you react?”

Daya’s unorthodox methods would have easily crushed anybody else. But it was working very well for Hilda. She said that her mind was getting controlled, her emotions were becoming calm, and her meditation was bringing her closer to the goal. Her greatest asset was she interpreted all his teachings in a positive manner. Once Daya asked her to see him at 4 a.m. the next day. So at 4 a.m. the next morning (it was cold) she went to the house where he was staying. She then stopped at the door as usual to breathe in and out to be sure she was pure enough for “His Holy Presence,” and then walked in quietly. (Even in the most serious and difficult situations Hilda never lost her sense of humor.) Hilda observed that the teacher was in bed, comfortable and warm under the covers. It seems he acknowledged her long enough to say, “Sit down and meditate.” She obeyed as usual but she “was freezing while sitting there motionless.” Suddenly her kundalini seemed to be on fire. She writes, “It was as if flames were shooting upward in my spine. I thought I was going to die. I inwardly said, “Then let me die. I would rather die than give in.” With that, the energy shot up my spine and a divine peace came over me. My whole body was in ecstasy. Something wonderful had happened. The sun was just coming up as I lightly walked home, feeling two inches off the ground. The city was golden and so was I…”

Daya had siddhis or occult powers. But he was a pseudo-teacher. He did not live up to his teachings. He was not pure. When Hilda heard that he visited a lady disciple and drank wine, she almost collapsed in horror. As she aptly put it, “My Golden Hero had clay feet.” After the initial shock she said, “I picked myself up, brushed myself off, and marched on…When Daya’s visa was up and he had to leave the United States, I was ready to see him off without regrets. I was anxious to wave good-bye so that I could put into action what he had been talking about…” She wanted to know what Ramakrishna and Vivekananda had experienced, and above all, she wanted to know if the teachings of Jesus work for those who walk the Earth down here? Hilda also made a firm decision not to teach anything she had not experienced herself. She said, “I had seen the erroneousness of a pseudo-teacher, a pretender, instead of one who lived the message.”

Once Daya was gone Hilda was on her own to experiment. For Hilda the next few months were “to be times of hard work, overwhelming happiness and despair, success and failure.” She would spend the whole day teaching in San Francisco then come home at night and pause only long enough to say hello to her mother and go upstairs to start meditating. She would spend the whole night meditating. She was obsessed, “but what a wonderful obsession: God.” She always carried a notebook. Even on trains and ferries in the midst of crowds going back and forth to San Francisco, she would try to listen to the inner voice and write. Her meditation had a direction. She not only wanted to be enlightened but she also wanted to be clear and pure enough to share with others, to help others also to become enlightened.

Working the whole day in San Francisco and meditating the whole night at home, often times for many months at a stretch she did not have any sleep. She went through many mystical and yogic experiences. She said, “I had to learn to trust the inner force implicitly, and I began to understand the connection between the inner world and the outer. I became aware of my intuition, or what I learned to call my inner space.” Once after spending the whole night meditating she got ready to go to San Francisco to teach dancing. She wrote, “Another night had passed. Where had it gone? Time seemed to stand still. I was at peace, but tired: “Well, never mind, perhaps I will get some sleep tonight.””

With no outer teacher to help her, Hilda was on her own doing meditation and pranayama – breathing exercises. She was struggling day and night to still her mind and control her senses. During one such struggle she had a vision. She said, “wham! — in the corner of the room there appeared a yogi, with deep-set eyes half closed, sitting in contemplation in lotus position under a tree. Not a word was spoken, not a movement made by this yogi, yet grace came upon me instantly, and the breathing exercises and meditation became easy. It was a complete turnabout from the difficulties of sadhana into a peace. This vision encouraged me to continue striving. It gave me an impetus to carry on by myself.” (Many years later when Hilda was in India and went to see the spiritual master Bhagavan Sri Nityananda of Ganeshpuri she realized that it was Sri Nityananda who had helped her that night in Oakland, California. She even saw a picture of him sitting under a tree, exactly as he had appeared in her vision in her room in Oakland ten thousand miles away!)

Hilda had the power to heal people. She did not go out of her way to exhibit this power. It was not her intention to be a healer. When people in difficulty came to her she quietly did the needful. But her attitude towards this power to heal was very humble. She said, “I have always been in awe of healings and to this day do not know how they take place, but that I know it is not my power but His. I look on at the healings which take place with the same wonder as the healed.”

Once when Hilda was staying with a family in a large cabin up in the mountains near Santa Barbara, California, she was invited by a friend, Helen Bridges, to a meeting where Swami Paramahansa Yogananda (author of Autobiography of a Yogi) would be present. The meeting was held at Helen’s home in Santa Barbara. The day of the meeting as Hilda was walking to Helen’s home she inwardly felt that it was to be a special day in her life. Of Swami Yogananda, Hilda wrote, “His large eyes shone like deep brown pools of light, and long shiny black hair hung past his shoulders. He wore an orange silk robe. I gazed in awe at his beauty. He started to chant and all at once light from his eyes shot out and seemed to enter me. It was like two streams of light force. It seemed as though he were addressing all his words towards me… I was drawn to him like a magnet… As he sang, his songs went deep within me…” That night after the meeting as she walked home through the quiet streets of Santa Barbara (the air was filled with the fragrance of flowers) Hilda was humming one of Swami Yogananda’s songs, “I will make you Pole Star of my life…”

Hilda’s second encounter with Swami Yogananda was held under very unusual circumstances. One night when she was staying at the cabin in the mountains she became very ill. She was having difficulty breathing. As she struggled through the night she remembered Swami Yogananda and felt he could cure her. The next day she asked her friend to take her to Santa Barbara. Once they reach Santa Barbara, Hilda decides to go to the home of Helen Bridges. The moment they reached Helen Bridges’ home, Helen walked out and without even greeting Hilda made the following remark: “Would you like to go to Encinitas to Swami Yogananda’s? A car is here, ready to go, and we are waiting to see who Swamiji wants to have come to him. The back seat is still vacant.” It was a long drive to Encinitas. When they reached Encinitas, they were taken to their rooms. As Hilda waited in her room, still very sick, she heard a knock on the door. She wrote, “I said in a weak voice, “Come in.” The door swung open and there in the oval doorway stood Swami Yogananda with an effulgence of light emanating from him. He spoke, but I did not hear him…” The mere presence of Swami Yogananda healed her. All her inner turmoil turned into jubilant feelings. Before leaving he said, “Stay with me here and I will take you to Mount Washington in Los Angeles when I go soon. God has sent you to me.” During her brief stay with him, at one point Swami Yogananda said to her that he would like to make her a center leader to teach Self-Realization work techniques and asked her to think about it. Hilda spent the whole night thinking about it. She wrote, “I balanced the scales in my mind and heart. If I stayed, I would know God, peace and security. On the other side of the scale, I wouldn’t know humans… I would not know the world of ordinary people with their passions, their likes and dislikes, and their discord. I would not know their fears. I knew that only if I went through the fire of hell and came out unburned could I truly say, “I love.”…” In her mind she goes on to address Swami Yogananda thus, “Swamiji, I say from my heart, though you asked me to stay, I cannot. I am like the wind which blows through the trees. The world is my home… You were a light in the night for a young girl. That searchlight will guide my way and will never die within my soul…” The next day she conveyed her decision to Swamiji and left.

Hilda’s routine of dancing, teaching and meditation continued. She was also giving classes on meditation. Sometime in 1947 when she was reading Swami Yogananda’s ‘Autobiography of a Yogi’ she was attracted to India. The feeling in her to visit India kept growing. She did not have any money but she was determined to go to India. Very soon she along with a few friends, who were also performing artists, started making preparations for a tour of India and Ceylon. Finally after many weeks of preparation they were on their way to India on a freight ship. Many years later when she was back in America, Hilda wrote, “I went to India as a dancer and gave concerts throughout the country. I left here with a one-way ticket, with eighty dollars in cash, and with a million dollars worth of faith….”2 When the tour came to an end after three years, Hilda alone stayed back and for the next fifteen years travelled all over India meeting spiritual masters and learning. Often these spiritual masters understood her financial situation (without her telling them anything) and helped her financially either by giving her cash or through their occult powers.

Once Sri Sathya Sai Baba of Puttaparthi advised her “Go beyond name and form.” During her nearly eighteen years stay in India, Hilda met many holy men and spiritual masters. Spiritually she received a lot from many of them. She had immense love and regard for each one of them. Yet she wondered who her real guru was. Finally she came to the conclusion, “I know without a doubt that my one and only satguru is the One and Only Within, the Absolute God, nameless and formless. My search is ended.” After returning to America sometime in 1965, Hilda settled in New York City and started to teach meditation. The size of her class grew from two students to more than a thousand in a short period of time.

On January 29, 1988, Hilda passed on in New York City leaving behind a legacy of love. Way back in California (before she went to India), as a young aspirant, Hilda once said, “What I had to learn was to love life in the midst of everything. My self-righteous attitude, my “I am S-p-i-r-i-t-u-a-l” spelled with a capital “S” was to be sandpapered off. I learned to love people no matter what.” She lived this way of life both as an aspirant and later as a teacher. “When Hilda laughs, the whole world laughs. When Hilda cries, the whole world cries. Angel wings softly stroke her brow…” – Jan (a friend of Hilda)

Mallikarjun. Jan, 26, 2012.

References 1. Saints Alive, Hilda Charlton, Page X2. Saints Alive, Hilda Charlton, Page 18.