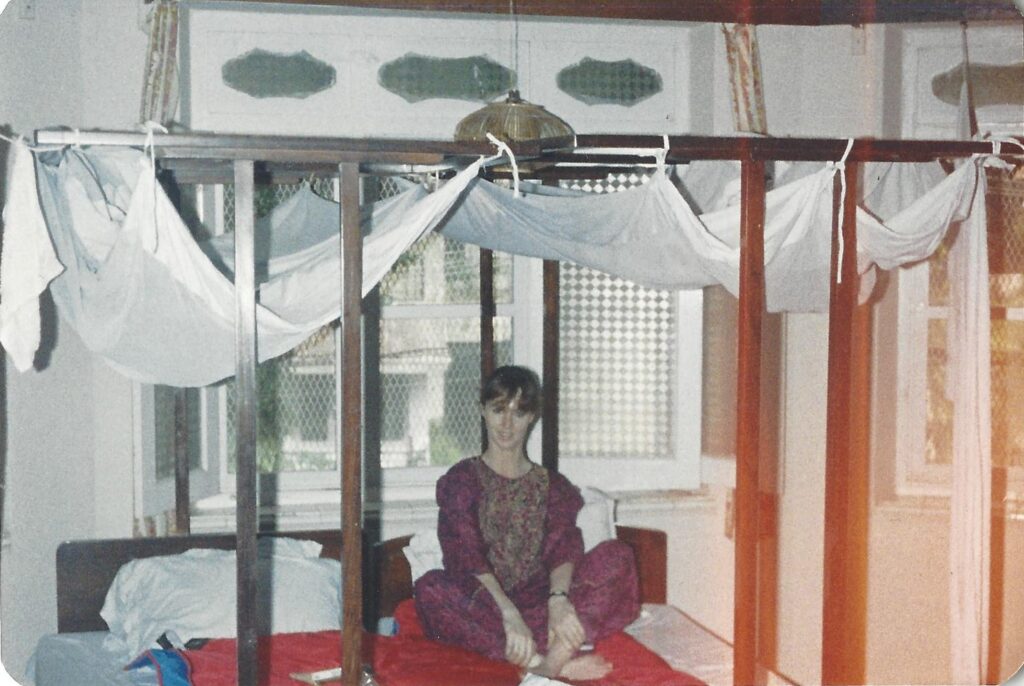

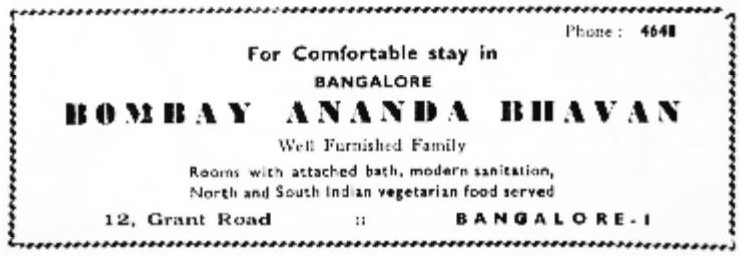

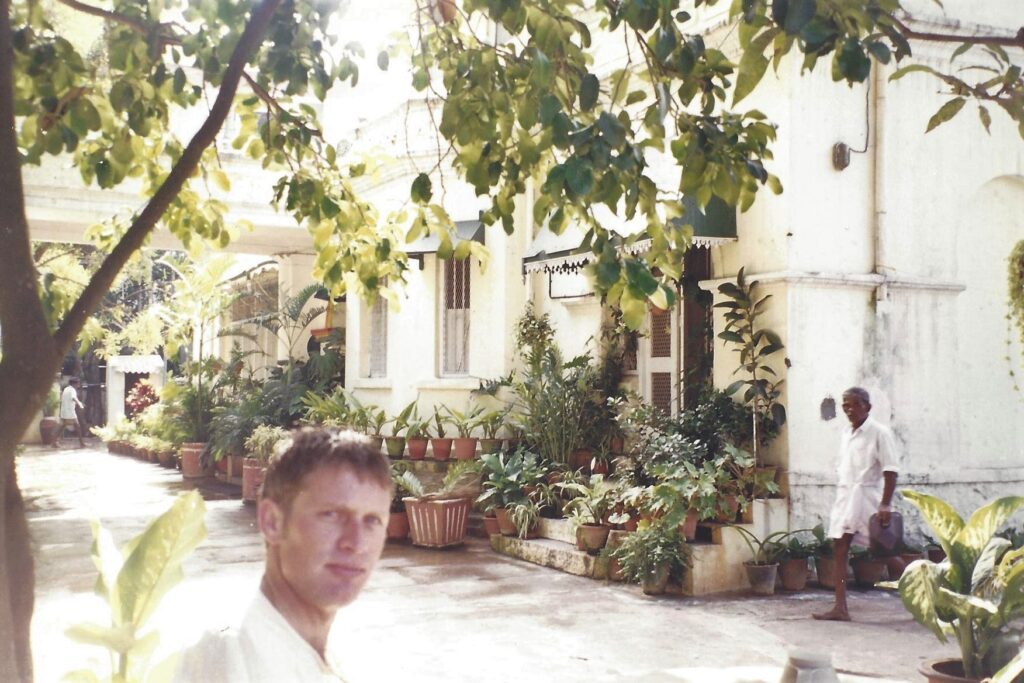

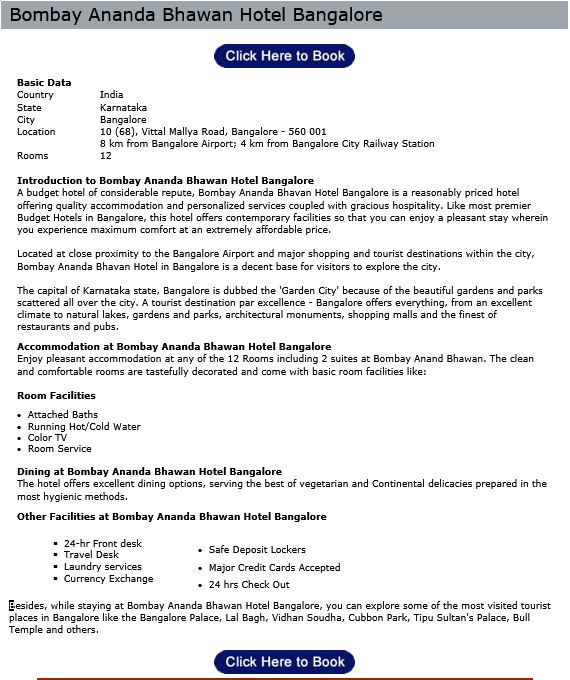

A devotees hotel from the past, the Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel, an oasis set amongst the Raj-era bungalows in the cantonment of Bangalore, India.

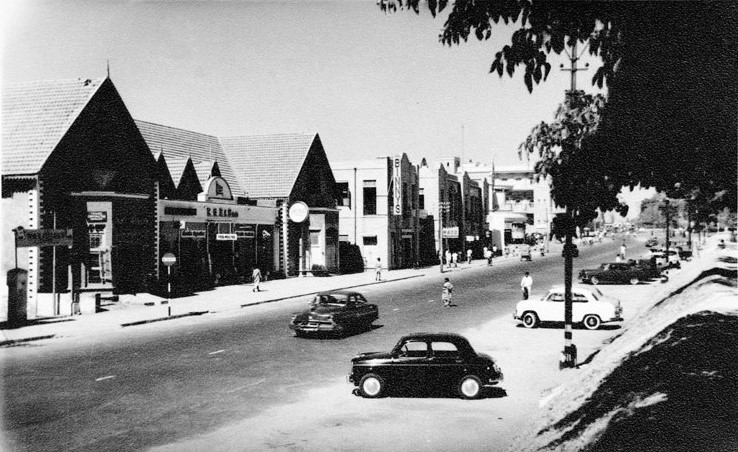

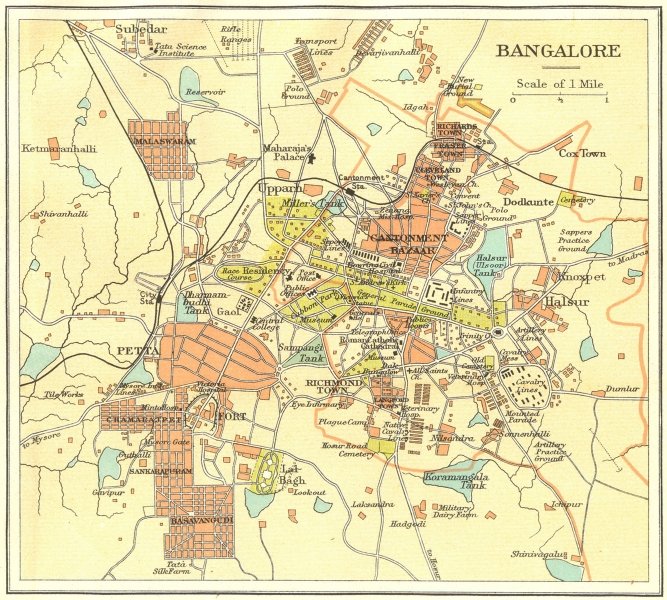

The Bangalore cantonment of bungalows, gardens, race courses, clubs, barracks and parade grounds for its mixed civilian and military population, was established in 1809, separate from the city.

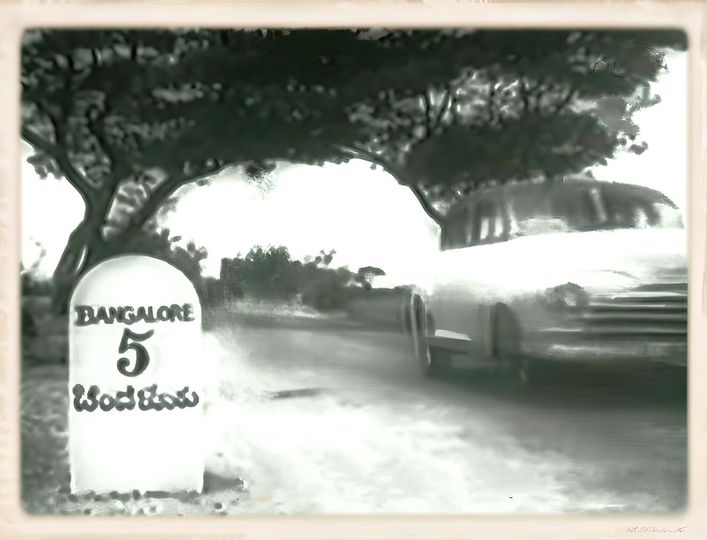

Many devotees of Sathya Sai Baba would stay here while Baba was at his Whitefield ashram ‘Brindavan’ approximately 16 miles away. There was very limited accommodation at the ashram, so many devotees opted to stay in either Kadugodi, where the ashram was – near Whitefield, or stay in the city. From here devotees would travel twice daily out to Brindavan for darshan in the taxis that operated out of the hotel. The hotel was also a popular transit place to and from the main ashram ‘Prasanthi Nilayam’ in Puttaparthi, 100 miles north, in Andhra Pradesh.

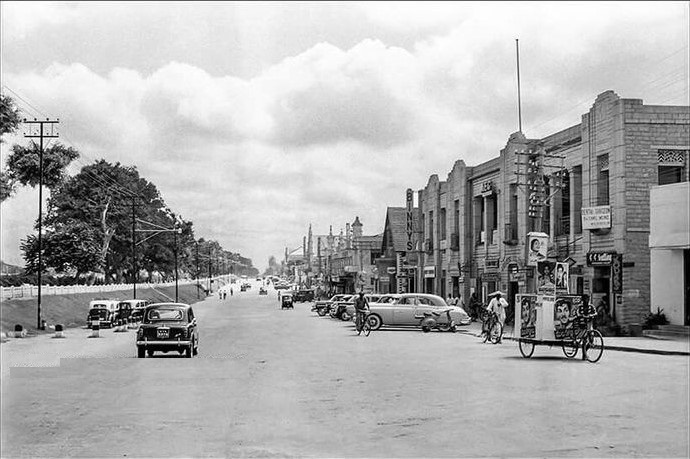

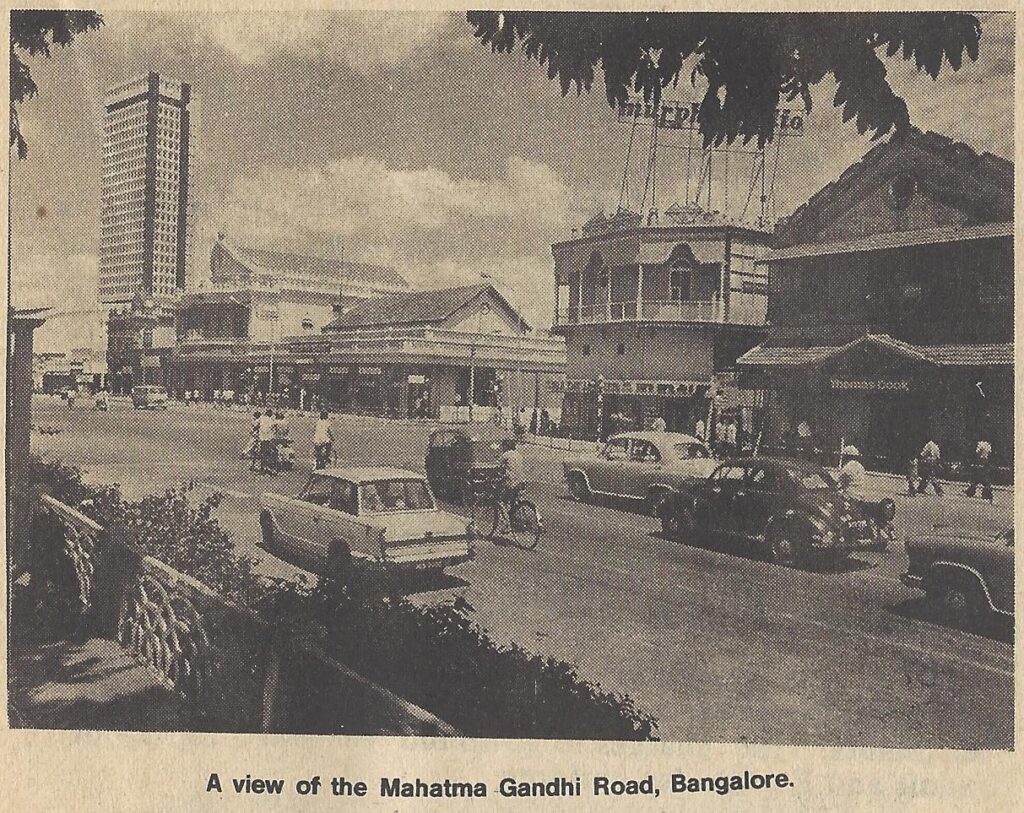

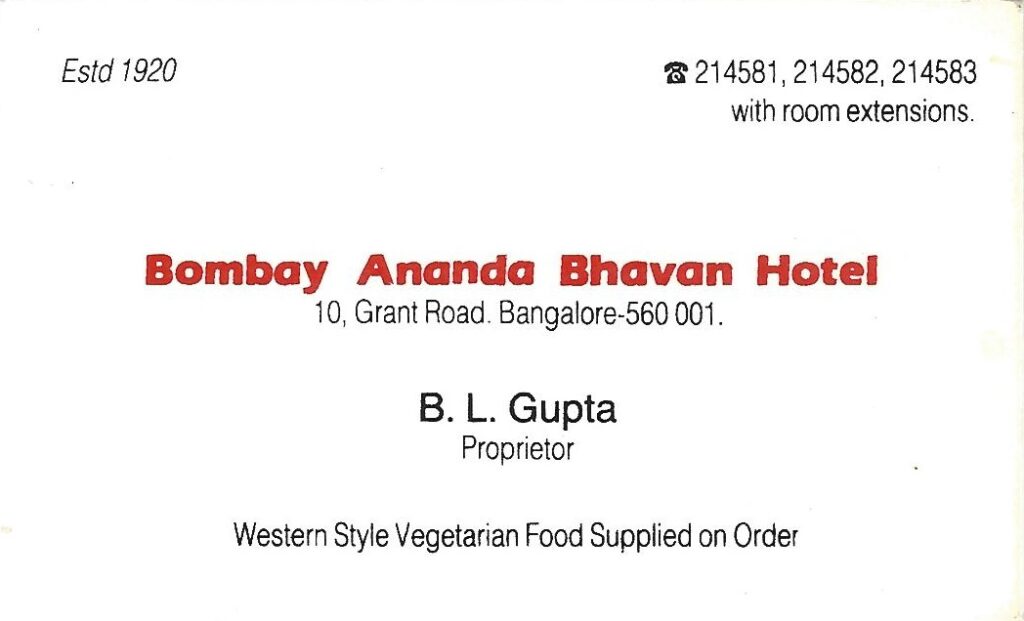

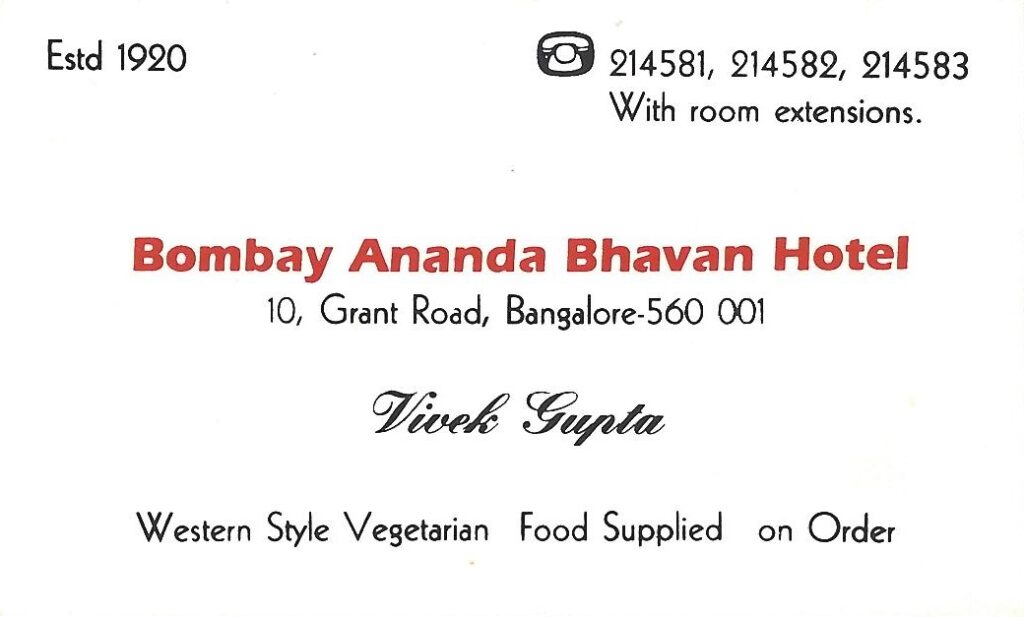

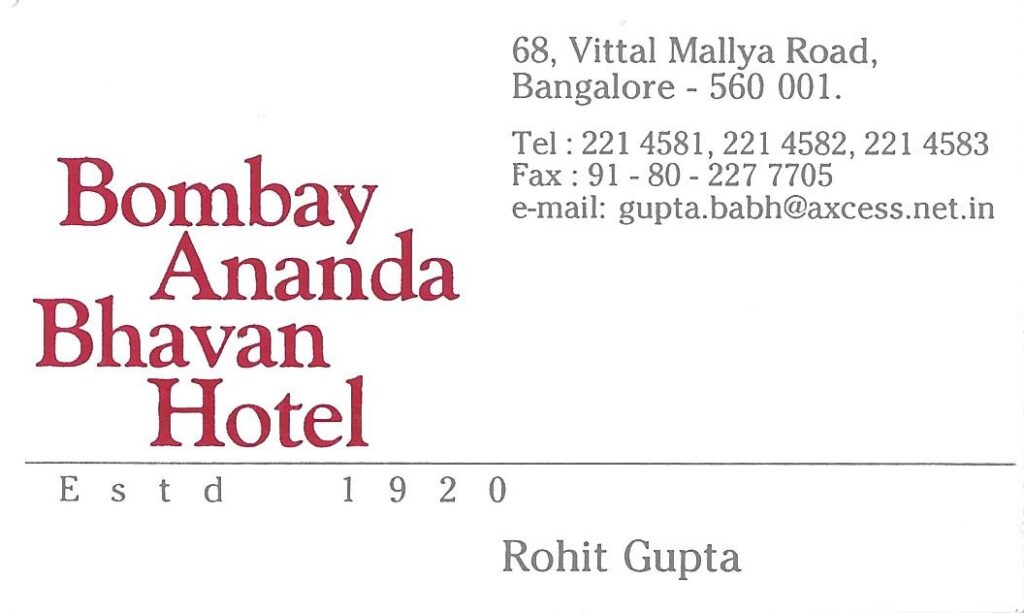

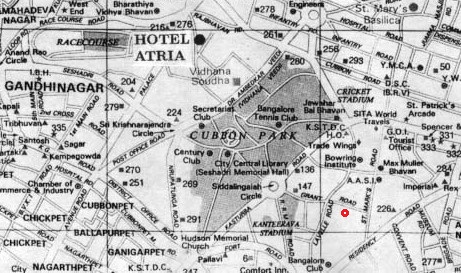

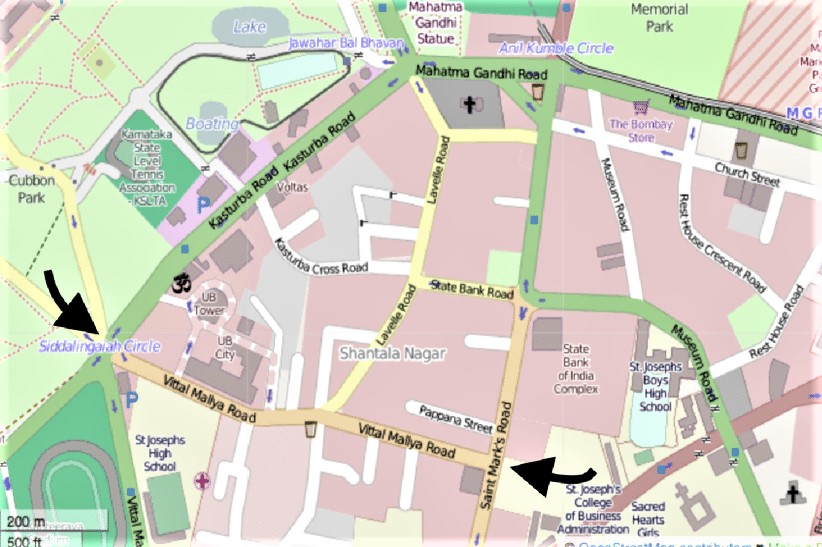

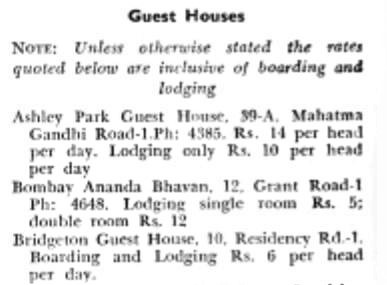

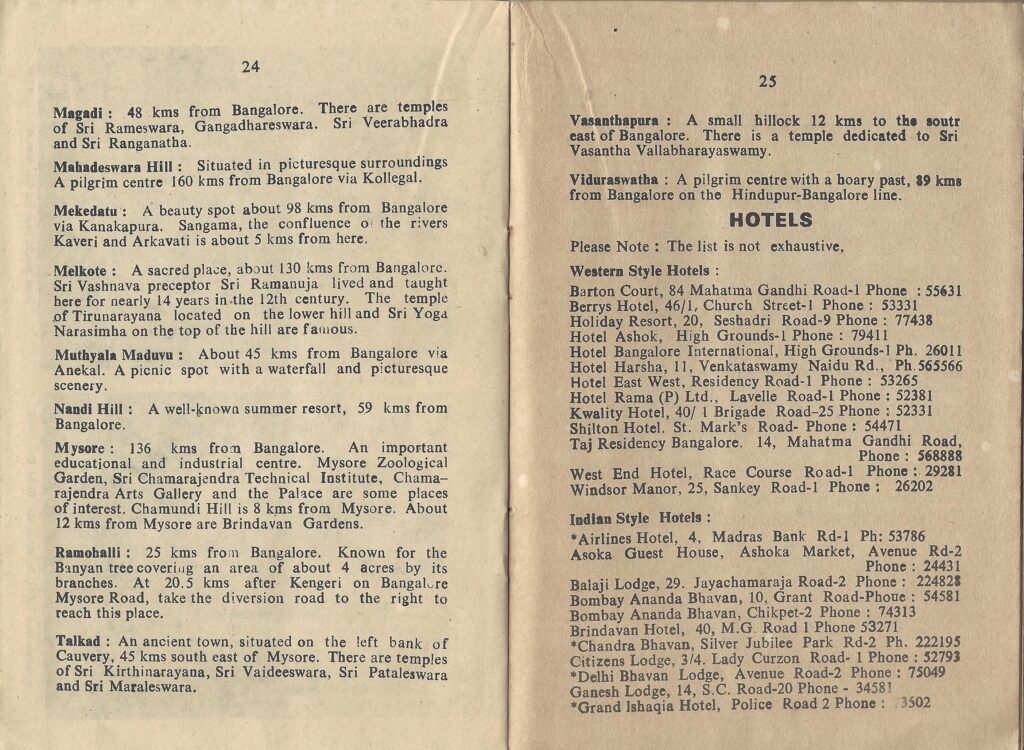

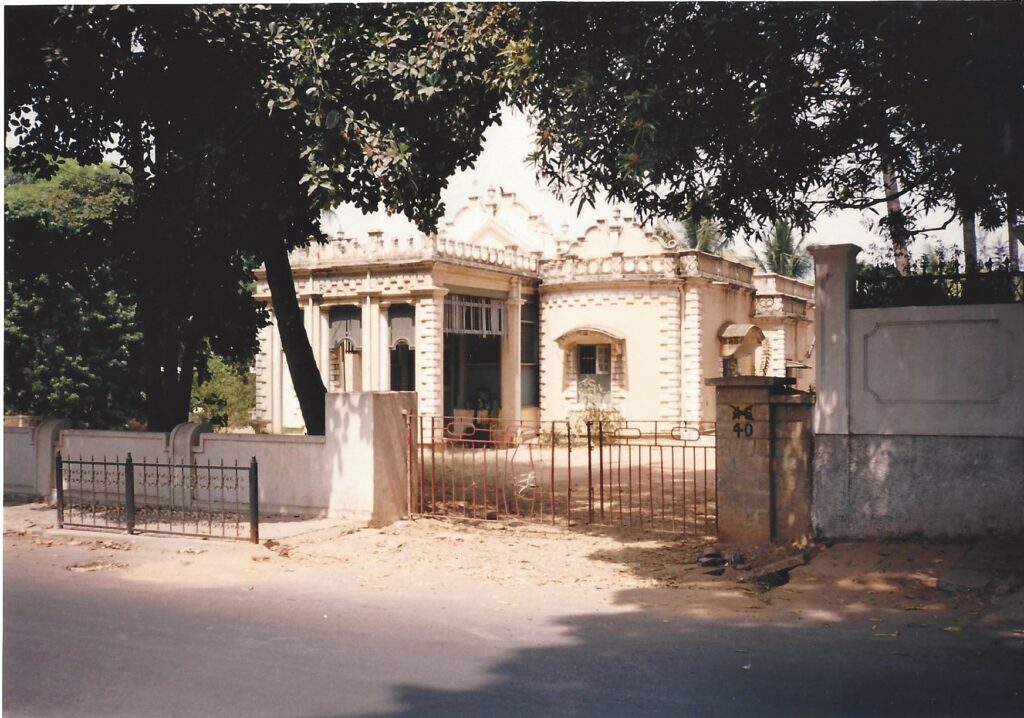

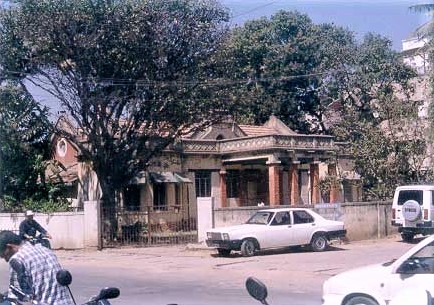

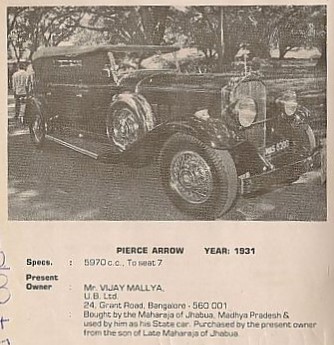

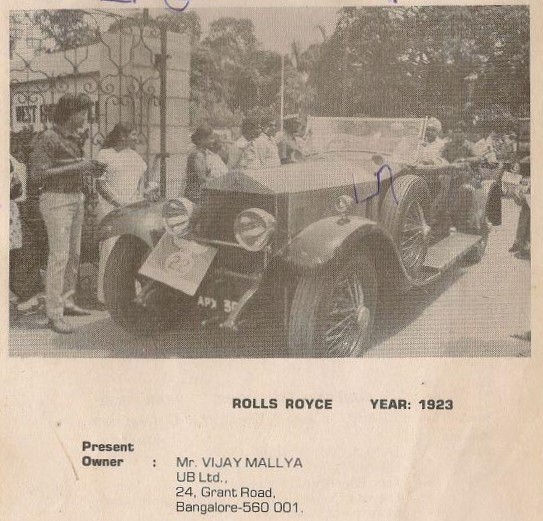

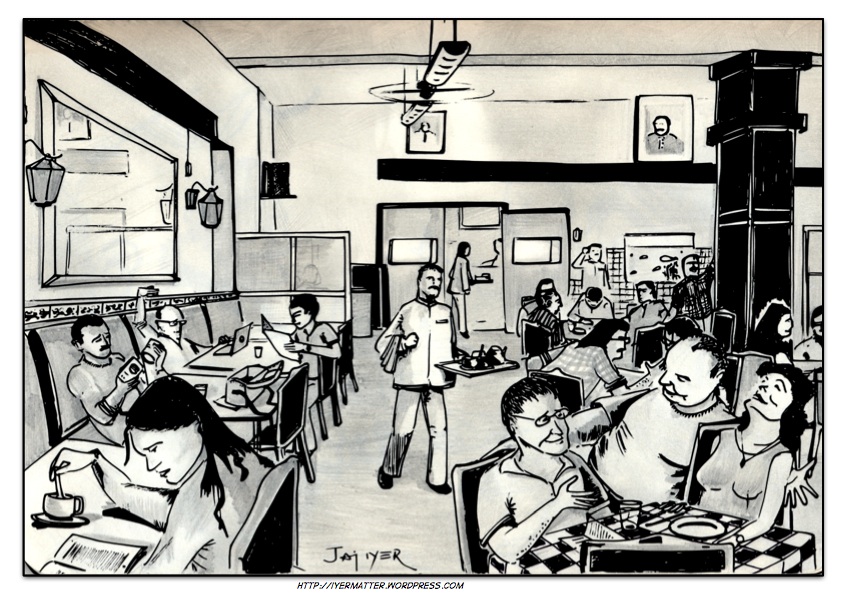

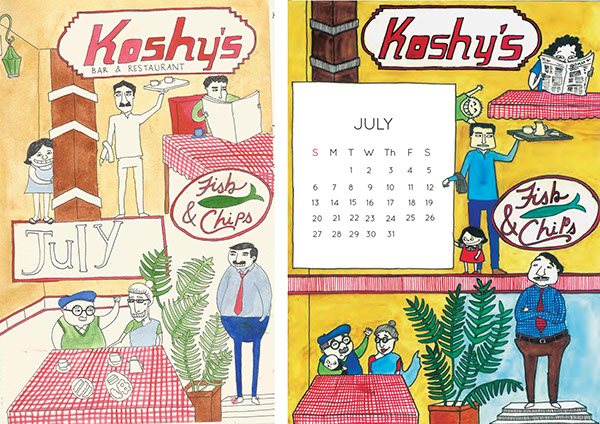

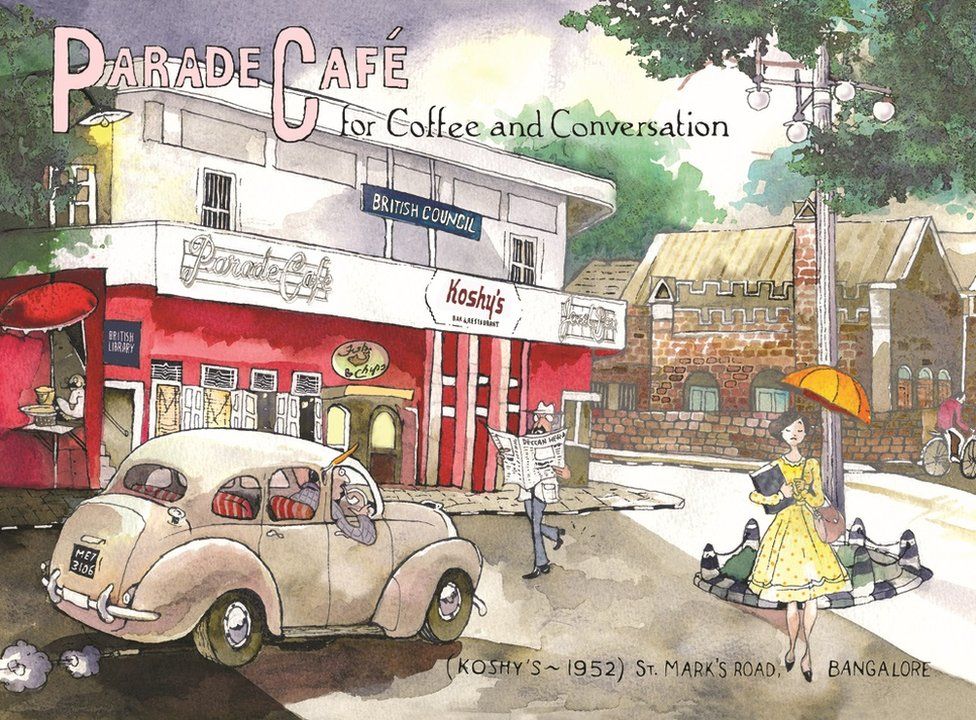

The original address for this 12-room establishment built in 1920, was 12 Grant Road (according to the 1963 Guide-book of Bangalore, which can be downloaded by the link at the end of the article) and then 10, before the renaming of the street, when it then became 68 Vittal Mallya Road. Vittal Mallya Road is named after the famous entrepreneur, Vittal Mallya, father of Vijay Mallya. The guest’s name and country of origin were displayed in the lobby, so no trouble to see who was checked in. Situated in the quietest area of Bangalore, the guests could easily walk to M.G. Road, via Lavelle or St. Mark’s Road to Koshy’s famous Bar and Restaurant. Koshy’s is today recognised as an ‘establishment of Bangalore,’ a very popular restaurant and hangout owned by the Koshy family since its founding in 1940. It is a meeting point for journalists, artists, theatre folk, students and foreigners. It retains an old-world charm with huge pillars and large fans. The Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel was demolished around 2005, and replaced with this commercial building, built by Anand Bhavan Properties Private Limited. In 2018, the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, stated that private buildings are the most poorly conserved in Bengaluru, in the past 30 years, the city has lost 75% of its heritage homes, with only 129 out of 510 surviving today.

Long-time receptionist was the quite beautiful Latah who kept the boys under control, including the head boy Muthu. She helped with many enquiry’s. If you were looking for someone who was not in, you would be kindly informed that they were “out of station.” One long term guest asked her where in the city she could buy Jewellery, looking at her as though she was a moron, she replied “Jeweller’s Street of course.” The boys had extraordinary long days and dossed down on the floor late at night only when all the guests had retired for the evening. Latah went home each night to her husband and family. Muthu saw his wife and family further south, only once a year and only for a week.

Part of the daily routine for Muthu and his boys was to keep the electricity running by resetting the breakers as they tripped (Bangalore’s power supply was notoriously, only mostly available at best), ensuring the hot water was on the boil and available for delivery through the antiquated piping system into the rooms. On more than one occasion guests helped him out with this by getting up into the ceiling with him to demonstrate the best way of keeping up with the problems. When the showers did not work, the buckets were in good supply and always available.

The main menu at the hotel consisted of puri bread, idli and other rice dishes, toast that came as ‘jam butter toast’ or ‘butter toast,’ toasted sandwiches, excellent omelettes of cheese tomato & coriander, tomato soup, tea (but not so much ‘bed tea’) and superb pots of coffee. While the owner Mr B. L. Gupta was running the establishment, his daughter in-law did most of the cooking in a traditional Indian kitchen out back in a dark corner of the building. Mr Gupta spent most of the day sitting in the lobby/reception area keeping an eye on things and didn’t talk much. His son had died and so Mr Gupta took care of his wife and the grandsons, who would go on to inherit the establishment and live on the lane next door in modern apartments. The grandsons, Bobby (Vivek) and Bindy (Rohit) Gupta did an amazing service keeping the hotel running in the years that followed.

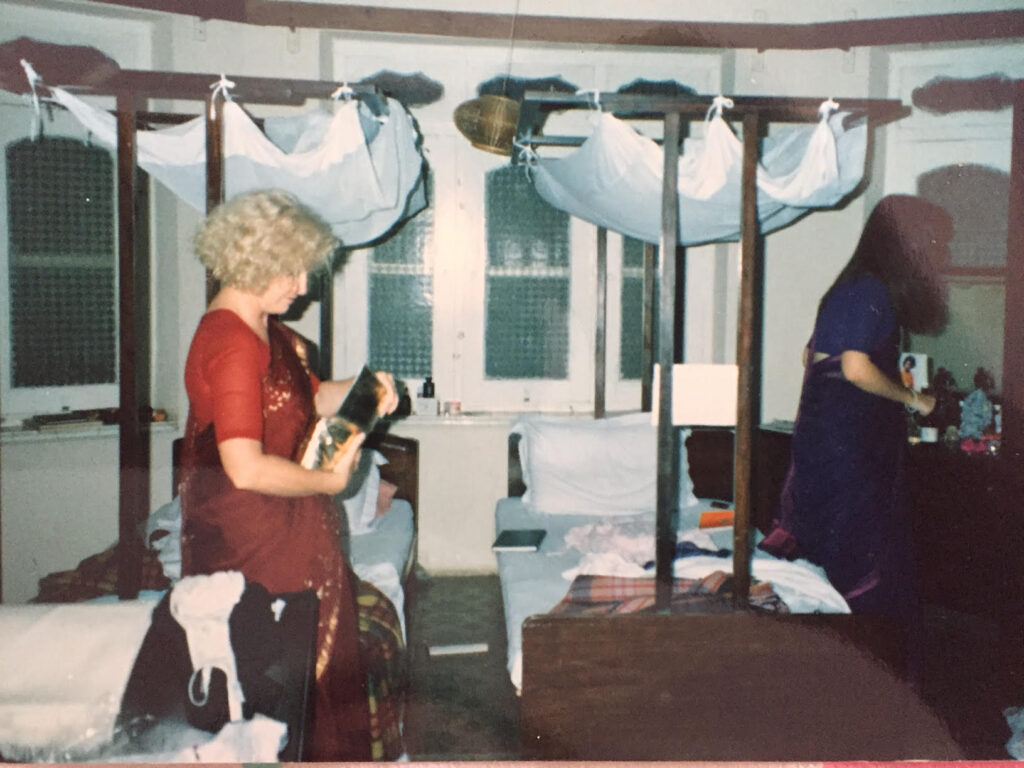

Many of the women guests were resourceful enough to secure items such as hair colour from outside the country, as India didn’t allow certain ‘luxury’ imports. This did take a little effort and time to arrange. Hair colour was available in India, however only in three colours, black, black and black. Bangalore’s best-known supermarket chain Nilgiri’s, was a main source for items and some devotees even sent taxis from Sai Baba’s main ashram 160 km away in Puttaparthi to the Brigade Road store in Bangalore to get soft toilet paper sold there. Indian made toilet paper tended to be very thin and non-absorbent back then.

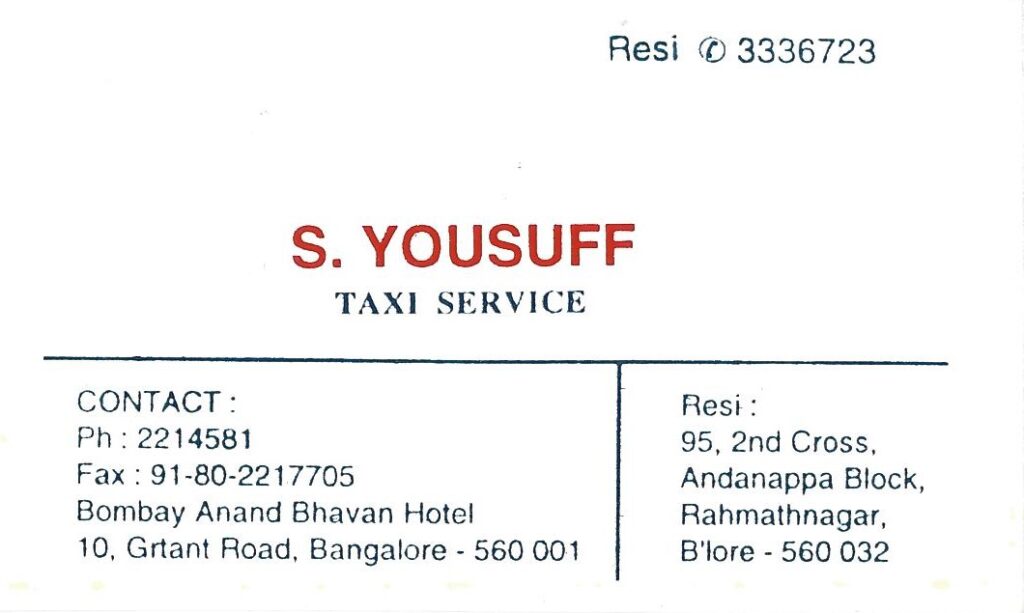

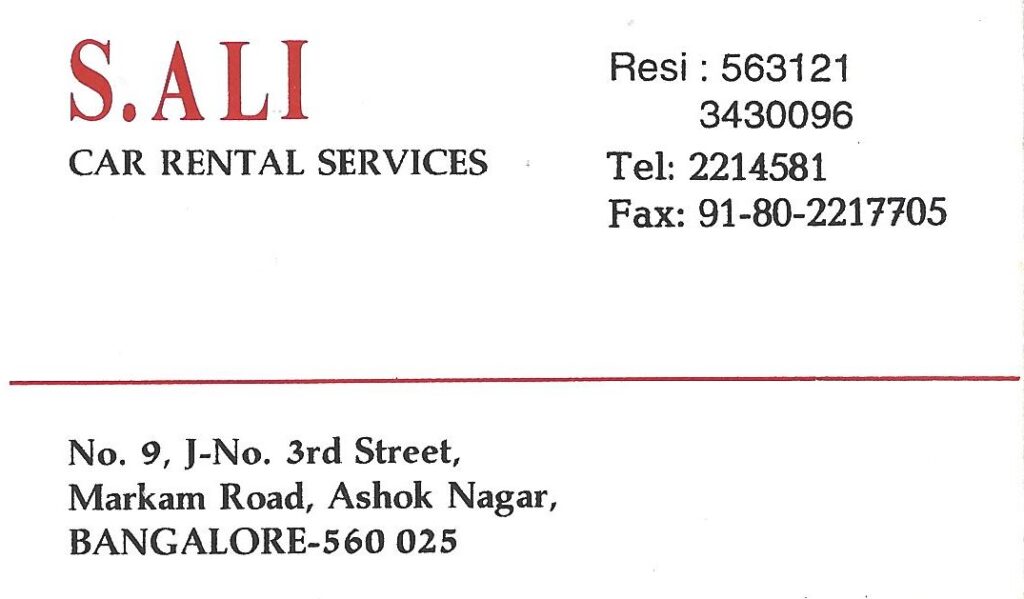

The hotel had its regular taxi drivers operating from there, the best guys in the world, Ali with an Ambassador with sometimes bald tyres, another operator with small and mostly uncomfortable Padmini, and Yousuff with a few cars, including a new Suzuki van. There were others that came and went as the patronage required. These drivers operated at all times and were often first with the news of where Baba was as he moved around between Puttaparthi, Whitfield, Madras and Kodaikanal.

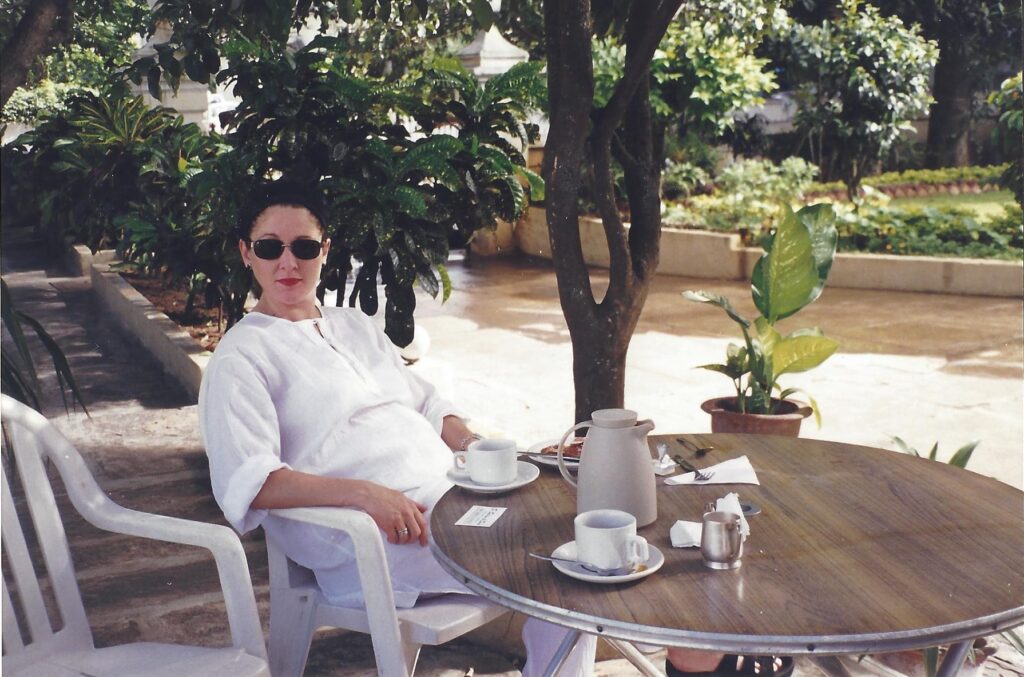

Many of the residents would take a buffet breakfast mid-morning at the Oberoi on M.G. Road after the early morning darshan of Sai Baba while he was in the suburb of Whitefield, just 19 km away. Some guests often spent part of their day at other 5-star hotels by the pool where for a few rupees they could get a decent shower afterwards, drying off with big fluffy towels, and all the while enjoying the silver service coffee.

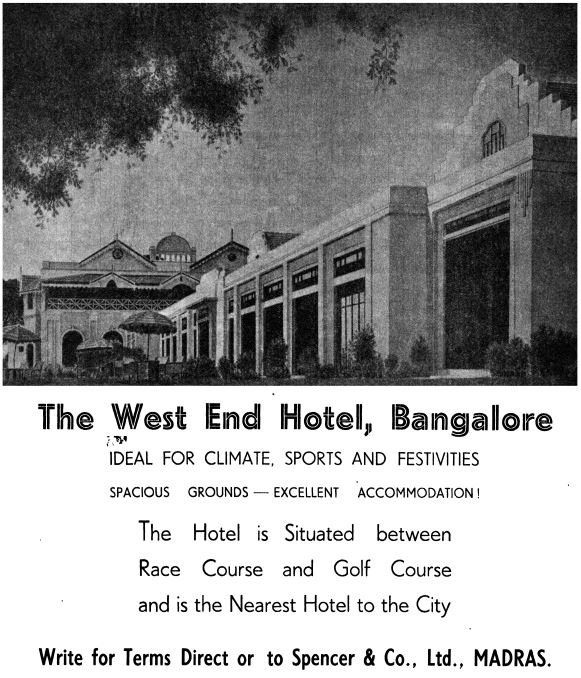

After a long day in the hot and dusty crowded streets with constant horn tooting, it was always a joy for guests to return to the cool tranquil hotel, where the boys had just watered the plants and front lawn in late afternoon, making it feel fresh and cool. In the evenings, some of the guests went to the Windsor Manor, the West End and other 5-star hotels, where they enjoyed excellent meals and service for so little.

The Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel had long-term residents from time to time and management were always patient with the time it took to receive any payment from them. The hotel was a safe haven for all the devotees of Sathya Sai Baba, who felt very safe and welcome and often felt his presence there.

Grant Road was renamed Vittal Mallya Road in memory of the former chairman of United Breweries in the 80s, after Vijay Mallya’s UB Group signed an agreement with the civic agencies for the road’s maintenance. During the British Raj, the area was part of the Cantonment and was then known as Maciver (Maclver) Town. Grant Road extended from Bishop Cotton Girls School to the then Tiffany Circle and along Sampangi Tank. Things changed when the Kanteerava Stadium was built on the tank.

Gradually the colonial houses were replaced by stylish glass-chrome buildings, there are just a few heritage homes remaining.

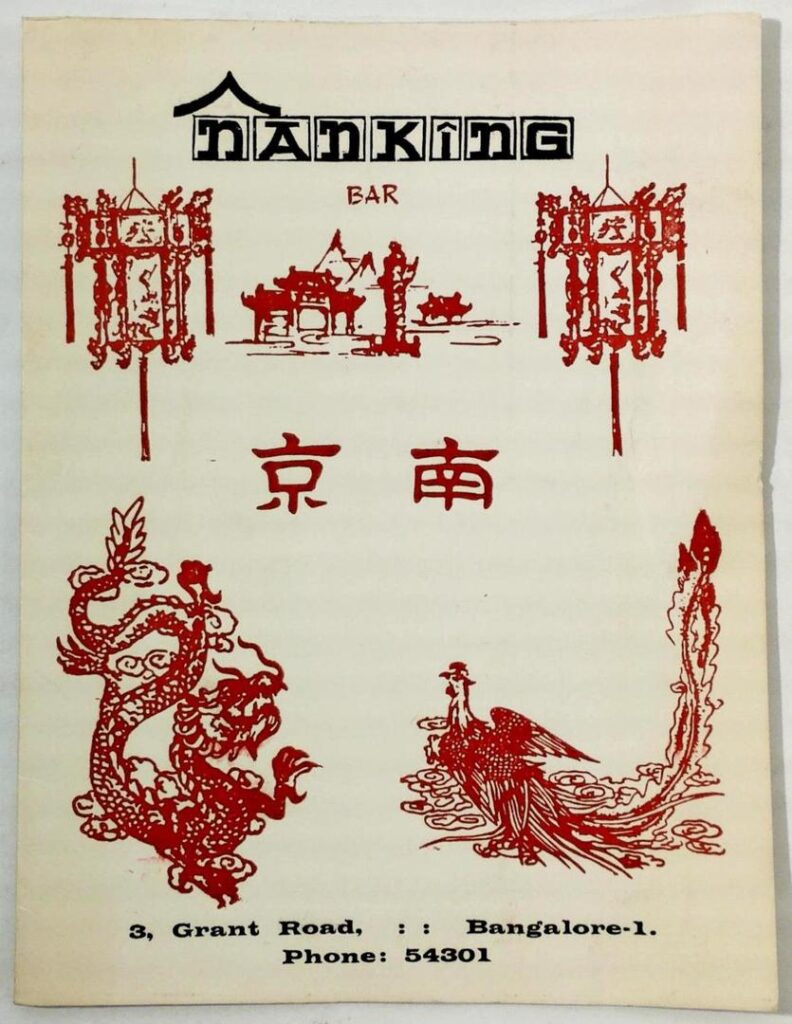

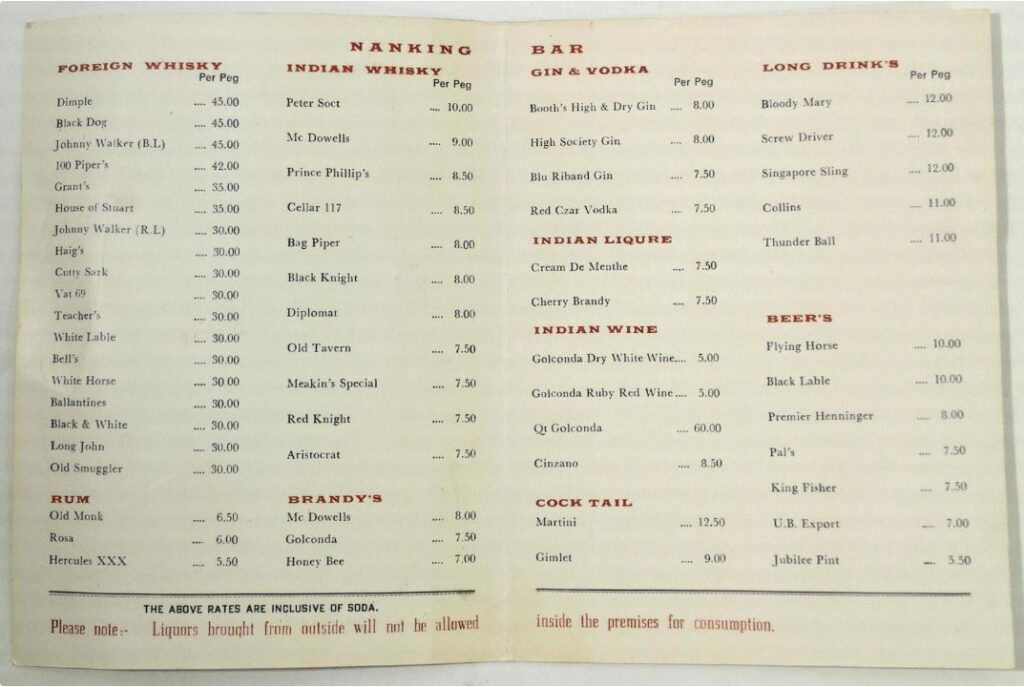

When Bangalore had few restaurants, Grant Road had three places to dine. Housed in colonial bungalows, each styled differently, the Shilton Hotel, the Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel and the Chinese restaurant Nanking which was then famous, apparently its owner cooked for Pandit Nehru.

When Bangalore had few restaurants, Grant Road had three places to dine. Housed in colonial bungalows, each styled differently, the Shilton Hotel, the Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel and the Chinese restaurant Nanking which was then famous.

Nearby Lavelle Road is now known to modern Benglaureans as a state-of-the-art, uber luxurious lifestyle hub, traces its nomenclature to an Irish soldier who, in his time, was the most prolific miner of Bangalore. Michael F. Lavelle, a retired Bangalore Cantonment officer who served in the British Army in the regiment that fought against Tipu Sultan in Srirangapatnam), was the first prospector of gold in the Kolar Gold Fields (KGF) region. The book Kolar Gold Fields Down Memory Lane written by Bengalurean Bridget White-Kumar, explains how Lavelle (in the 1870s) travelled 60 miles in a bullock cart to Kolar with the prospect of finding gold, the journey taking him no less than a fortnight.

On September 16, 1874, Lavelle obtained mining rights in Kolar from the Mysore British government, which extended to over twenty years. Starting in a village called Urigaum (Oorgaum), he was amazed to find that the deeper he dug, the more gold he found.

In 1877, Lavelle sold his licences to Madras-based Kolar Concessionaires for a handsome amount, before returning to Bengaluru. His successful gold-mining expedition and the resultant prosperity made him a popular figure in the Bengaluru English circuit and the British Commandant renamed the street where he lived as Lavelle Road and he was rewarded with a grant of 7 acres of land between Grant Road (now Vittal Mallya Road) and Lavelle Road.

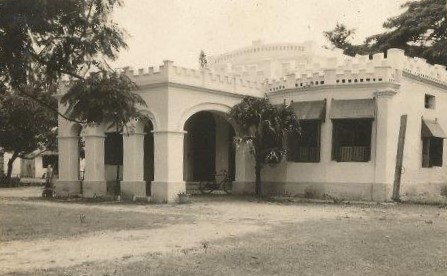

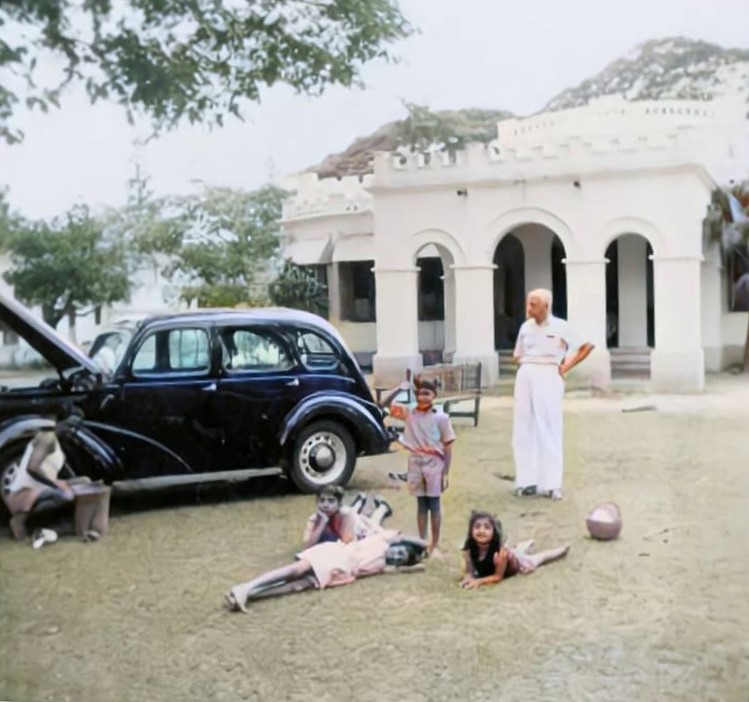

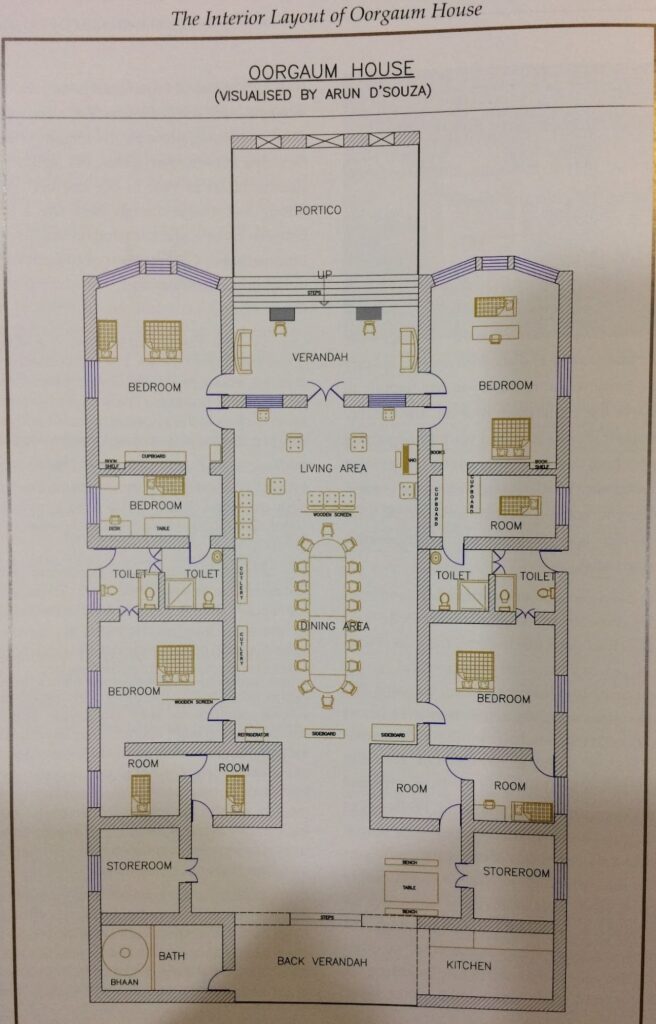

Lavelle built an imposing bungalow of over two acres on Grant Road that was characterised by its white, pillared portico, battlemented terrace and a large compound. The property was called Oorgaum House (in memory of Lavelle’s first mining expedition) when it was sold to Peter George D’Souza (a high-ranking civil servant in the provincial government of Mysore) and his wife Rose D’Souza in 1918. Lavelle eventually returned to England, where he spent his last days. Source: economictimes.indiatimes.com

Oorgaum House built by Michael Lavelle, for the wedding reception of his daughter, Tingley. This was named after the town Oorgaum, in Kolar district of Karnataka; where Lavelle had discovered the gold fields along with contemporaries. The house was to be inherited by his son, who sadly was killed during the Great War. Oorgaum House, on then Seshadri Road, was purchased from family friend Rao Bahadur Deshmukh Shama Rao in September 1917, for Rs.9000 by Michael Lavelle. He renamed his house Oorgaum House after his first shaft that he sank in Urigaum, KGF as a reminder of his good fortune.

Mr and Mrs D’Souza bought Oorgaum House from Lavelle in the early 1900s. The whole property of three acres was later divided among the 17 children of Mr and Mrs PG D’souza and the place is known as D’souza Layout. Oorgaum House was demolished in 1988 and apartments constructed in its place. Many of the apartments are owned by members of the PG D’Souza family. The Area was later renamed PG D’Souza Layout.

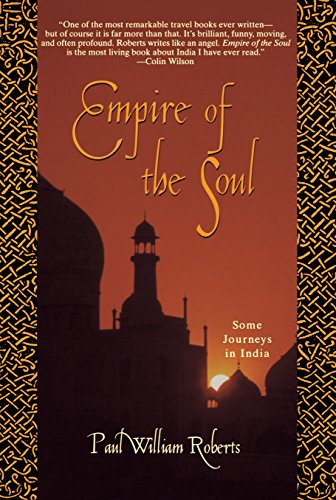

Empire of the Soul

The Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel, 1992: Author Paul William Roberts recounts checking into the hotel in his 1996 book Empire of the Soul.

Bangalore, from my porthole, lay spread out like a vast flat garden. On a plateau high above sea level, it was essentially that in 1974. Now it’s more like an Indian Silicon Valley. Tall rain trees waved their ragged arms in a mild breeze. As I stepped out, I noticed the air had markedly cooled and dried compared to Bombay’s Turkish bath. We walked over to what resembled the airport in Casablanca: a low building, a control tower, some basic radar equipment. The luggage was wheeled from the aeroplane on a huge cart to an area beyond two high chain-link gates. On the other side waited an orderly, well-dressed crowd. Everyone was meeting someone. Flower garlands were placed over heads; children reverently touched the feet of elders; small pujas were performed: hand-sized trays of burning camphor waved around as friends and relatives clapped and chanted, praising the gods for a safe arrival. With us it’s a hug, then hand over the bottle of duty-free. Indians do things with grace and style. They’ve had more practice at it.

Far from being harassed by competing taxi drivers, I noticed only one taxi waiting outside the airport, alongside a manicured lawn containing riotous pink hibiscus beds. And someone was already commandeering it. A little distance off were several of the covered three-wheel motorcycles known as autorickshaws. I consider them a distinct improvement on the old rickshaw; who feels good about having some emaciated octogenarian in a loincloth and turban hauling him barefoot around the city streets? There is a drawback: most of these vehicles are piloted by maniacs. I was approached by a short man with a crazy smile, no shoes, and a filthy tea towel wrapped around hair that shot out like black palm fronds.

‘Autoauto?’ he said, as if it meant something. I had the address of a cheap hotel, the Bombay Ananda Bhavan (literally the ‘Bombay Bliss House’) on Grant Road. I asked him if he knew the place.

He nodded in that unreassuring South Indian manner and hefted my bag over to the buggylike rear of his machine. Then he proceeded to get into a nasty argument with one of his colleagues, a man who could have been his twin, that was clearly related to my custom and seemed to reach the verge of blows but went no further.

Cursing and spitting red gobs of betel-nut juice through rusty-looking teeth, the driver finally kick-started his sputtering engine and we took off like a gnat in high wind. I bounced from side to side like a bell clapper until I learned to brace myself with steel struts supporting the auto’s canvas roof. Between the driver’s handlebars and the murky windshield were attached several small framed portraits of gods and film stars. In their midst, an incense holder held two burning joss-sticks emitting a smell like charred bubble-gum.

We turned abruptly onto a broad boulevard teeming with every vehicle known to humankind, entering the vast honking caravan like a weaver’s shuttle. I wondered if my driver had a personal problem with everything and everyone else on the road. When I dared to look, there were faded but elegant Raj-era bungalows – some, in their cuteness of detail, almost gingerbread houses – on either side. The bungalows of Bangalore attained enough fame to have once merited a picture book of that name, but were not famous enough to survive into the nineties. With its tolerable climate and strategic position in the centre of the South, the city was a major army base during colonial times – indeed, was still a significant base in the third decade of independence. As the focal point of Karnataka state, Bangalore, which borders communist-influenced Kerala to the west and the troublesome and occasionally separatist-minded states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh to the east, is still valuable in military terms. India’s bewildering variety of politics usually coexist in a kind of querulous harmony. Usually.

Relaxing his grip on the accelerator for the first time in fifteen minutes, the driver zigzagged through cows, donkeys and people, coming to a jarring halt in the heart of a stupefyingly chaotic and noisy fruit and vegetable bazaar.

‘Bombay Ananda Bhavan?’ I asked, hoping it wasn’t.

The driver raised a grimy palm. He clambered out and began a belligerent conversation with a skinny and toothless man who must have been at least ninety-five years old. Both lit up beedies, the tiny, lung-ripping cigarettes wrapped in leaf that in those days cost about a cent for fifty and still weren’t worth the price. The old man pointed in several different compass directions over the course of this conversation, and I detected a look of desperation in my driver’s eyes as he glanced my way.

‘Grant Road,’ I reminded him.

I soon learned that, in India, even someone who lived on Grant Road might be unable to tell you how to get to Grant Road – not that this would prevent him from offering utterly wrong directions. There was a certain shame in admitting you didn’t know, so people frequently and confidently offered complex and entirely erroneous instructions. The driver evidently knew this and was not about to head off in the five different directions suggested by the old man. He waylaid a porter carrying about a ton of huge red bananas on his head. This man had been using tar for toothpaste, by the look of his mouth, and had one eye so bloodshot it could have been recently boiled. He uttered what sounded like one word a hundred syllables long. The driver pulled on his beedie, brows knotted. Then he jumped back and, sitting sidesaddle now, zipped off at maximum velocity, terrifying animals and any humans unfortunate enough to be in our path.

Twice more I endured similar stops, and presumably similar misinformation. Finally we hit Mahatma Gandhi Road – there is at least one of these in every town and city the length and breadth of the subcontinent. Then we turned onto St. Mark’s Road and off this onto a quiet, lushly tropical street of large, stately houses and bungalows . . . actually labelled Grant Road.

The whole history of Indian cities could be told through street names. The signs reading Grant Road and St. Mark’s Road have now gone, replaced by Vithalpatai Road, by Indira Nagar, or some such – yet the old names survive unofficially. Grant Road is still somewhere a taxi or auto driver will take you, if you’re patient.

The Bombay Ananda Bhavan proved to be one of the stately houses, its title on a weather-weary board looking at once out of place and a sign of the times. A semicircular drive drew you up to a robust, monsoon-proof porch over steps leading to double doors. After a screaming argument over the fare, my driver flew off, his machine sounding more and more like an angry bee trapped in a jar.

A reception desk with a bell greeted my entrance. There was no sign of human life. I rang the bell, hearing an odd guttural gurgling, apparently from beneath the floor. I rang again, shouting out that I was here. Nothing. Just the subterranean sounds of a viscous drainage. A clock ticked. A pleasant breeze blew in, carrying perfumed greenhouse smells on its wings. A fly the size of a small bird – or possibly a small bird the size of a fly zoomed straight for my nose, veering drastically away at the last moment. I looked in a room to my left – a bed draped in mosquito netting – and a room to my right – a bed draped in mosquito netting, and an armoire the size of a van. Then I peeked behind the narrow reception desk, to discover a bearded man in a T-shirt and lungi sound asleep on the floor.

The occasional gurgling was his snore, which aggravated a standardised fly that was busy gathering sebum from his glistening nose. It darted back and forth to the safety of a nearby shelf each time the man’s mouth puckered with another imminent snore. He had toenails like a bear, this sleeper, and the soles of his feet looked like desiccated mudflats, riven with cracks half an inch deep in some places. They weren’t like leather; they were leather.

He looked serene, with his hands behind his head. I called to him quietly. No response. Finally I shouted at him. Beyond an irritable gurgle, still no response. This was no ordinary nap. In the end I took him by the shoulders and shook, all but slapping his face as if he’d OD’d or passed out from booze, or both. Finally his droopy eyelids fluttered.

Standing up, he could have been Peter Lorre’s son. Both eyes looked off to the side, adding to the impression that he wasn’t certain that I was there, that he was there, that it wasn’t all a dream. Pretending he hadn’t just woken up, he spoke gibberish and performed menial and meaningless tasks – dusting the counter, checking his saucer-sized wristwatch, and closing the heavy shutters about one-tenth of an inch. Then he indicated a ledger, handing me a ballpoint pen from the Sheraton Hotel, Kathmandu. The last entry in this huge tome read: ‘Maynard Billings, San Diego. A really beautiful stay.’ I wrote my name and address, assuming it was premature to comment.

‘Mr. Billing,’ the man said, pointing at the previous entry with swaggering pride. ‘He like this place too much. Very good man, Mr Billing. Very good. You know him?’

I confessed I did not.

‘You want room, is it?’

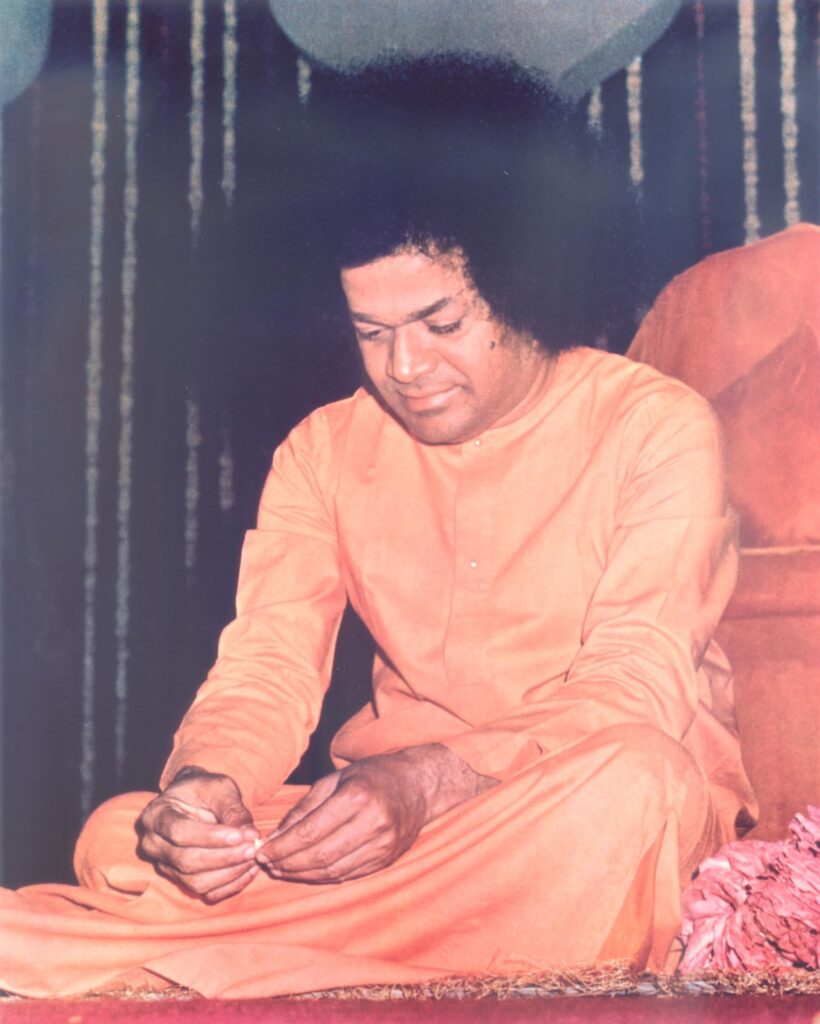

On one wall hung a framed photograph of Sathya Sai Baba, the local holy man, looking like Jimi Hendrix’s grandfather. A garland of flowers placed around it perhaps a week before gave the image a funereal appearance.

‘You come for bhagavan?’ asked the concierge, noticing my interest in the picture. ‘Bhagavan’ means God, basically, but in India, where all that lives, and much that is inanimate, is holy, it is a term liberally applied to gurus, yogis, sadhus, film stars, musicians, teachers, and even politicians. I had indeed come to Bangalore ostensibly to see the famous ‘Man of Miracles,’ Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba.

‘Currently out of station,’ the concierge informed me.

‘Where?’

‘Puttaparthi going.’

Sai Baba, I knew, generally stayed near Bangalore, but had his main ashram in the village of Puttaparthi, in Andhra Pradesh, where he was born. Puttaparthi was notoriously difficult to get to, I’d been told, at least a day’s journey away.

I did not want to give this sleepy man the satisfaction of seeing I was disappointed. ‘Any other gurus in the area?’

He pondered the question seriously, as if I’d asked him to recommend a good local restaurant. I assumed this was a preamble to saying no, but I was wrong. He mentioned someone apparently named Siva Bala Yogi – or possibly Sivabalayogi.

‘Where do I find him?’

Near the Bangalore Dairy was the closest I got to an answer.

My room had three four-poster beds in it, their mosquito nets hanging in the air like ectoplasm. It also had six doors – one an entrance, one leading to a bathroom containing a tap, a bucket, and a squatter, and the other four leading into adjacent rooms. I washed, lay down on bedsheets that felt as if they’d been baked in an oven full of dust, and listened for an hour to a couple of geckos wheezing endearments at each other across the peeling whitewash of the wall. A calendar adorned it, emblazoned with a highly retouched image of Mahatma Gandhi at his spinning wheel. He literally glowed with health and looked about eight years old. According to the mahatma, it was June 1963. From what I’d seen of Bangalore so far, it would be hard to refute this. In fact, it looked more like 1943 out there still.

Ian McGillis interviewed Roberts for the Montreal Gazette in 2015;

Delving back into the years with Roberts, a unifying thread soon emerges. In common with many who came of age in the 1960s, he was drawn to all things Indian partly through the evangelizing of the Beatles. In his case, though, the process was a little more direct. Through the sculptor father of a friend he ended up at a party at George Harrison’s house in the stockbroker belt outside London, where the guitarist passed him a copy of Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi. A lifelong identification ensued, one whose depth is evident when Roberts is asked to name a favourite among his books.

“Empire Of The Soul was really written from the heart, a love letter to India,” he said of the book, drawn from extended visits in the early 1970s and early 1990s, that has been an essential item in the backpack of many a subcontinent traveller. “When you love a subject, it changes everything. Although I predicted India would soon amaze the world, I didn’t think it would be so soon. I often feel I should update some parts to reflect a country on its way back to where it was before the invaders and colonizers stole everything and crushed a great civilisation under their boots. The wounds of colonialism are now healing fast, though, and the book needs to show an India that made it, rather than one trying. It is the only country where I kiss the ground upon arrival and feel I’m home at last once more.”

Other visitors to the hotel

Koshy’s famous Bar and Restaurant on St. Mark’s Road

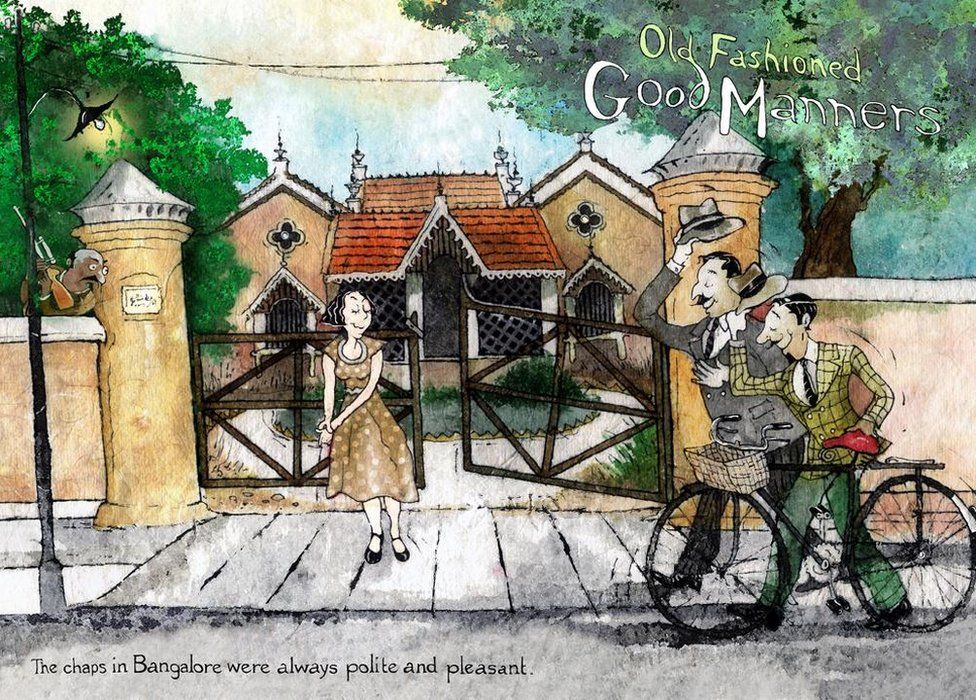

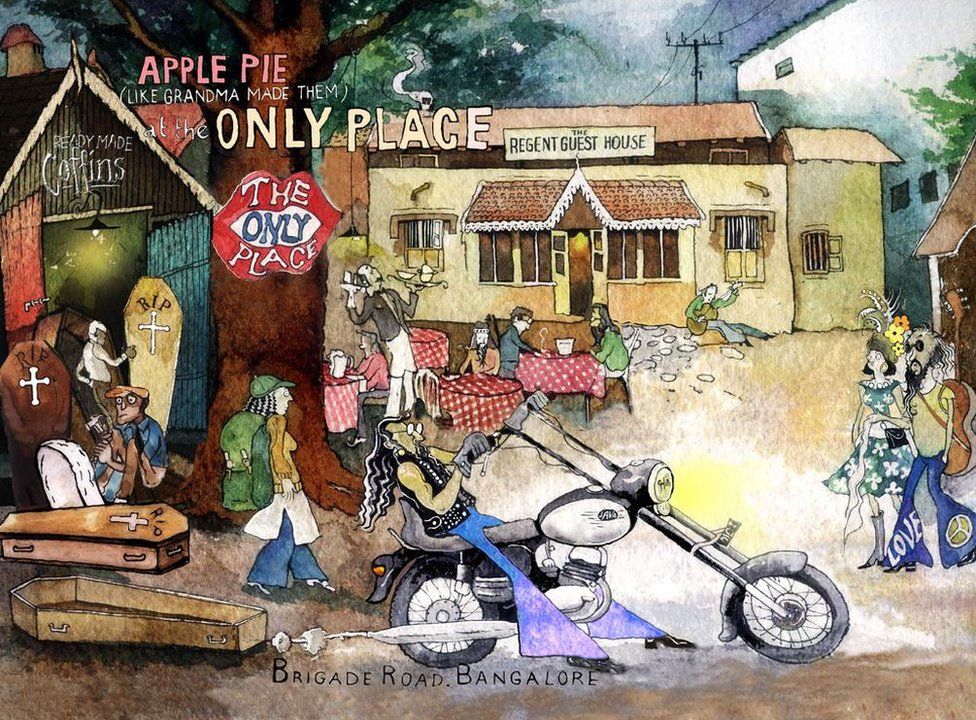

Bangalore’s very own cartoonist and illustrator, Paul Fernandes, has created works of art that are true to what Bangalore used to be and the old Bangalorean vibe. Fernandes has created a series of watercolour cartoons that portray Bangalore from the 60s and 70s. The series includes Bangalore’s famous landmarks that are till date famous, favourites, and popular. His inspiration comes from his childhood as he states,” Our old house was torn down to build a set of apartments for me and my nine siblings. It was a huge house, with beautiful gardens and 40 fruit trees. When it all came tumbling down, it compelled me to look at the changing city. And I started drawing places that I remembered fondly while I was growing up.”

Bangalore cartoonist draws ‘good old days’ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-31617988

About the Book ~ “I was born in Bangalore in 1945, the sixth of a family of seven. In my childhood, Father would be transferred every other year and we would move to a new town, a new school, a new second language.”

“Two facts gave me a sense of identity. Mother was the eldest of a family of seventeen children. And we had a hometown called Bangalore.”

From this prosaic starting point Peter Colaco’s Bangalore sweeps back to the turn of the 20th century and forward to dawn of the new millennium. He discovers that between his mother’s ancestral home on Grant Road, where he was born; and his father’s house in Fraser Town, where he lived for many years, his experiences represent a century of Bangalore’s eventful history.

The book is a sequence of loosely connected essays and anecdotes. It often borders on serious comment, might even pass as pop-sociology, but is even more enjoyable simply for its humour, superbly complemented by Paul Fernandes’ water colour sketches.

A rare and rather unique addition to the Bangalore reader’s bookshelf. In fact, to any reader’s bookshelf.

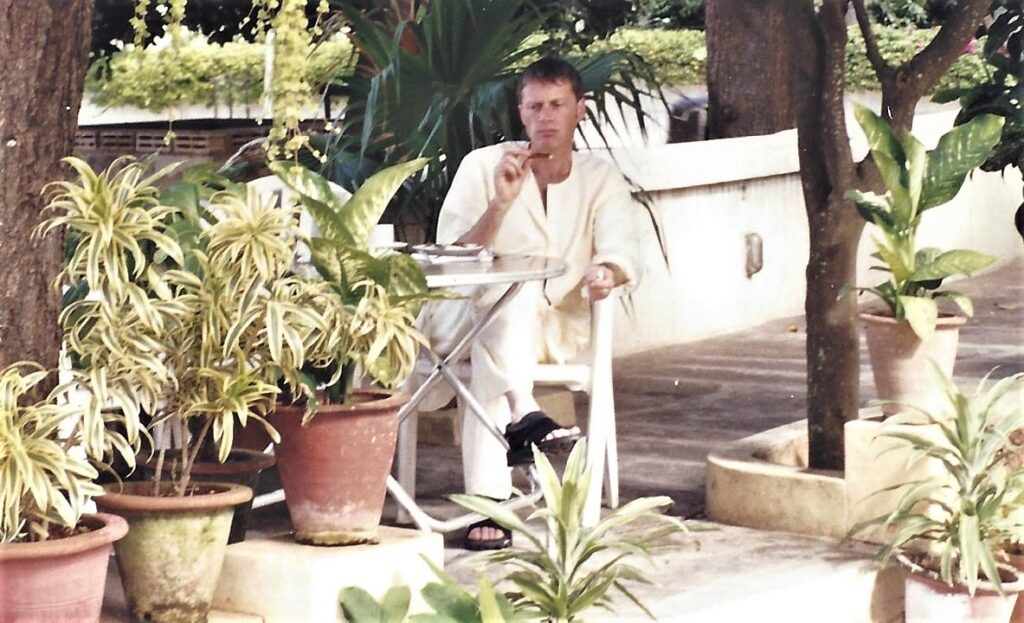

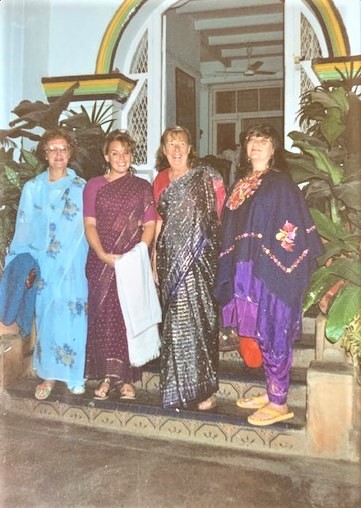

More photos taken at the Bombay Ananda Bhavan Hotel

Hotel residents and devotees in Whitefield and Kodaikanal.

The Taxi Drivers who operated out of the Hotel

“The Hindustan Ambassador was based on the Morris Oxford and started production in 1958 and continued in various forms till 2014. As a symbol of India’s automotive history, there is little else that defines motoring in the country.” Bobo Dutta. bobodutta.com.

The taxi operators out of the hotel were in no way similar to Delhi’s ‘International Backside Taxis’ mentioned in William Dalrymple’s City of Djinns: A Year In Delhi, his charming, unpredictable, and usually tardy couriers for the duration of his and his wife’s stay at Mrs Puri’s while writing the book. This taxi company was located nearby, behind the iconic India International Centre. The company name is derived from the postal address, that in India seem more like directions than a specific address. Indians often refer to the relative position to a landmark for an address, such as opposite, behind, or near. This is more used by the postman to easily determine where the delivery address is. In the case of the ‘International Backside Taxi Company,’ it was situated around the backside of the India International Centre. Validating this methodology, there is in Delhi a sign adhered to a pillar advertising the services of a Proctologist with directions to the surgery, shown as a curved arrow with the directional explanatory note ‘Around Backside.’

His regular driver was the irrepressible, faithful and spirited Mr Balvinder Singh, who told Dalrymple “In my life six times have I crashed. And on not one occasion have I ever been killed.”

Mr. Balvinder Singh of the International Backside Taxi Company took the Dalrymples on hair-raisingly fast rides through the throng of Delhi traffic, all the while cursing other drivers and pointing out attractive women along the roadside. “He swore at innocent passers-by, shouted graphic insults at rival drivers and hooted his horn as if his life depended on it: BEEP BEEP BEEP BEEP! “You Hindu Bloody Donkey Chap!”

He twice weekly offered to drive Dalrymple to GB Road, the red light district of Delhi, “Just looking,” he would suggest, “Delhi ladies very good, having breasts like mangoes.” Above this however, he believes in hard work and remains perplexed by roadside beggars: “Why these peoples not working? They have two arms and two legs, they are not handicrafted.”

“Handicrafted?”

“Missing one leg perhaps, or only one ear.”

“You mean handicapped?”

To which Balvinder Singh proudly replies: “Yes, Handicrafted. Sikh peoples not like this. Sikh peoples working hard, earning money, buying car.”

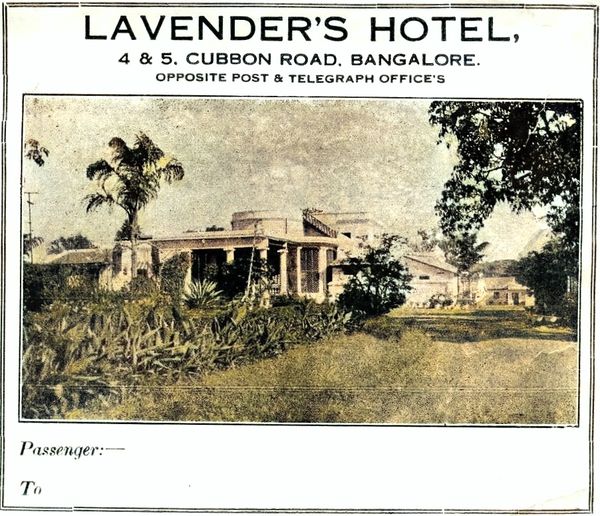

Regent Guest House

Another Hotel used by devotees was the Regent Guest House that was located down a long driveway opposite the Opera House, on Brigade Road.

Surbhi Gupta writes for the Indian Express – It’s past three in the afternoon, and the place is relatively empty. A couple walks in asking if there is anything left. But the owner, 62-year-old Mohammed Hassan, announces that the shutters of his kitchen are down. They will only open at 7 pm now, for dinner. Tucked in a corner of Bengaluru’s Museum Road, this is The Only Place — one of the first American diners to serve steaks and burgers in the city.

Founded by Haroon and his American wife Alice, the restaurant was located at the bottom of Brigade Road, and is now on Museum Road.

In 1965, Haroon Sulaiman Sait left behind his family business of textiles to open Regent Guest House on Brigade Road, on a property that he inherited. “My uncle started making breakfast for the guests, many of whom were expatriates. There wasn’t much of continental food in the city back then,” says Hassan, who runs the diner with the help of his daughter Rufqa, 25. They are Cutchi Memons who migrated from Gujarat’s Kutch over a century ago.

Regent Guest House attracted a lot of foreigners — Peace Corp volunteers from the US, college students, Iranians and Palestinians. Sait, eventually, got introduced to steaks and burgers by the guests. “He also started making Iranian dishes like Bamia curry and Ghormeh sabzi, and made pastas and pizza in the early 1970s,” Hassan says. Danish workers and the Japanese also started frequenting the place. “One Japanese gentleman liked the food so much that he made a sketch of lips smacking and called us ‘the only place’. That’s how the name and logo came about,” says Hassan, who joined Sait in 2003. It is also when the eatery shifted to its present location.

With beef dishes as the USP, they serve a variety of salads, soups, steaks, burgers, sandwiches and pastas. Some of the popular dishes include the All-American beef burger, chateaubriand steak and Apple pie. The burger that sold for Rs 2 when they started is sold for Rs 200 now.

Since Americans have always frequented the eatery, and it has enjoyed a close relationship with the US embassy in the city as well, the American Thanksgiving is an annual celebration here. So is the fourth of July. “But after 9/11, it was stopped. We used to gather at the Bangalore Palace for a picnic… people bought burgers from us for the occasion. But it became a concern for the US consulate, so it was discontinued,” he says. When the cast and crew of the David Lean film, A Passage to India (1984), landed in Bengaluru to shoot, the diner was their go-to place. It has also served corporate heads like Azim Premji, Kiran Mazumdar Shaw and fashion designer Prasad Bidapa.

Hassan is unfazed by his competition. “They don’t have our steak or apple pie to offer. We don’t have to serve liquor to sell our food, while others can’t run without liquor,” he says. But Hassan is, however, concerned about the future. “With elections around the corner next year, we don’t know what will happen. If the BJP comes to power again, beef can get banned in Karnataka as well. Then our business will go for a toss,” he says.

Francis Mola writes – It was set in a time and place and with a cast of characters that could have stepped off the pages of a road novel. There were Peace Corps Volunteers throwing Frisbee and playing touch football in the dusty courtyard. There were street performers, snake charmers, magicians doing their tricks, and beggars looking for a handout. There were backpackers staying in bare bones rooms for ten Rupees a night and Haroon its owner, scooting in out on his Jawa motorbike or giving orders to the cook Mr. DiCosta in the kitchen. We might all remember it differently, but what would a selection of anecdotes from our Peace Corps years and India 89 be without some memories of The Regent Guest House? The saying goes, “if you return to a place from the past it will never be as you remember it.” Things change and The Regent Guest House was no exception.

The Regent Guest House

If you didn’t know that The Regent Guest House was tucked into a back lot off of Brigade Road, you could have easily missed it. There were no signs or advertisements that lead you to it. The Lonely Planet Travel Guide for India was still twenty-five years distant and the internet was science fiction. Travelers heard about The Regent by word of mouth or the jungle telegraph and every Peace Corps Volunteer, and most American and European backpackers that passed through Bangalore, found their way to Brigade Road and down the alley alongside of Nilgiri’s Grocery. All of the India 89ers stayed there when they came in to Bangalore for a weekend of r&r or a visit to the Peace Corps office in Richmond Town. The Brindavan or the Rex, a short walk from the Regent, were acceptable substitutes with a similar standard, but lacked its personality.

Haroon was the owner of the Regent Guest House and its essence. He was cordial and helpful to all of his guests, but I think that he had a special affinity for the Peace Corps people that stayed there, and formed bonds with some that lasted a lifetime. Haroon was trim and dashing back then with intense, lively eyes, an easy smile, and with a passing resemblance to the photos of the leading men that were on the billboards outside of every movie theatre. I remembered him as always being on the move, probably because running the Guest House required it, but mostly I suppose, because it was his general disposition. One guest described him aptly as an object in motion and said, “objects in motion tend to stay in motion,” and that description was still applicable when I met him again many years later.

A bed at the Regent cost a bit more than a dollar a day, if you changed your money on the black market. It was the right price for a Volunteer’s limited living allowance and for the world travellers and “dharma bums” who lived on a shoestring. Judging by its name the Regent promised lodgings a little more elegant than they were in reality, but its dozen or so rooms were on a wavelength that let its guests feel at home. It seems shabby when I look at the photo from 1972, but I didn’t seem to notice it then. It was relatively clean and not different from any other small Indian hostel or hotel, and as a seasoned Peace Corps Volunteer, I was used to spartan accommodations. In our villages, we were weaned off comforts like toilets and running water, and the Regent had the luxury of both. For the rest, Volunteers had a flexible attitude as to what were considered necessary amenities.

In late nineteen seventy-one the Peace Corps was nearing the end of an era in India because of the diplomatic turmoil fuelled by U.S support for India’s arch enemy Pakistan in the Bangladesh War. As a result of these contentious relations, and a growing mood of nationalism, the Indian Government cancelled future Peace Corps projects and would not consider new ones. It was about that time that The Regent Guest House evolved into the Only Place, and I noticed that it began to change from a laid-back hang-out for Peace Corps Volunteers and foreign workers to a stop on the Southern leg of the “Hippie Trail”. Volunteers became a minority, replaced by backpackers and the acolytes of Satya Sai Baba, whom many Indians, and a growing number of Western followers, considered an incarnation of the God Shiva. These spiritual seekers came to the Regent to take some time off from the asceticism of the ashrams in Whitefield or Puttaparthi. I guessed that they visited Bangalore to have a beer and eat something other than lentils and rice. Some of them wandered around the Regent with hand-lettered cardboard signs hung on their necks that said, “I am observing silence,” and many seemed as though they were always in a state of dreamy contemplation, looking as though they had just found some profound cosmic truth. It was most likely “Bombay Black” that gave them that look because I noticed that they were groggy in the morning and had a buzz on in the evening. They scurried into hiding when the police came to check visas and passports. Because of the ongoing diplomatic strife caused by the Pakistani War, the authorities considered all Americans and long- haired foreigners an invasive species and wanted them out of the country. Haroon never asked to see a passport or visa, as was the law regarding Indian hotels. He welcomed everyone, and when it happened that some guests stumbled on the road to Nirvana or became ill, or got too much of a good thing, be it self- awareness, salvation or gangha, he was there to help them.

Everyone has heard the expression “You can’t go home again” You can of course physically, but there is a price you pay for it. Sometimes we change and places remain the same, sometimes places change, and remain the same only in our memories. Thirty years after I left the Peace Corps I wanted to take a step back and relive that time, and went looking for the cool and green Bangalore that I remembered. Instead, I found urban sprawl, tech yuppies, traffic chaos, and unbreathable air. I also went looking for the Regent Guest House, in some version of how it was in 1970, and instead of the old, rambling villa on an unhurried Brigade Road, there was a bustling, kitschy, shopping mall. However, when I stepped inside, the first door I saw led to the new Only Place Restaurant, where I found our friend Haroon, sitting at a desk in the back directing operations. His once thick black hair was speckled grey, and gravity and time had played its tricks on his physique, but when he removed his reading glasses to get a better look at me, I got a glimpse of the Haroon I remember, with the same contagious smile and charming manner. Hanging on the wall behind him was a framed photo of some of the volunteers in our group. Looking at it was like stepping into a time machine and I felt a pang of nostalgia as he reverently took it off its hook. In an instant, we were back, wrapped in the brightness of those times with all its volunteers and nomadic guests passing in review.

Places change. I thought that I had no expectations as to what I would find when I returned to Bangalore, but I was projecting the past, looking for vestige of the city that existed only in my imperfect memory. In a curious twist of fate, the restaurant, that many years earlier was the province of Peace Corps Volunteers seeking temporary respite from the arid Kolar plains, or a cheap eatery for scruffy travellers in tie-died kurtas and T- shirts, was now the domain of conservatively dressed businessmen dining on steaks, fries and apple pie. I realize that logically, there is no other reality than the present. My head understood that, but part of my heart was elsewhere. I left it back on the once uncongested areas around Brigade and M.G. Roads.

Sarah Osman writes for newstrailindia.com;

There was a nawab from Hyderabad who came there every summer with his family and retinue of servants to Regent Guest House. (A happening place where people from all over the world came to stay or just loiter. The hotel and my house were in the same compound.) He had a son my age. Every evening the nawab would take his begum and son for a walk up Brigade Road and buy him toys and whatever he wanted. Once I too was invited to join them. He insisted on buying me toys too, but I refused. He was most put out, and would not take no for an answer. So I told him he could buy me an Enid Blyton book instead, which he did. Yes, from Paramount Book Shop! Of course.

Many years went by and the nawab and his family did not return. Until one day, when I was in the 9th standard, the doorbell rang and there stood the nawab. He had come to say hello (or rather, aadaab) to me with a gift in hand. They were now settled in Bangalore permanently and had found a house on Richmond Town. The gift was (a la Tagore’s “Kabuliwaala”) an Enid Blyton book! And stupid me, I refused it saying – “Oh, I don’t read these anymore!” I feel so bad when I think of it now, that I didn’t have the tact to accept his loving gift gracefully. His disappointed face was a picture! God bless his soul, he was one of the kindest, sweetest men I have ever come across and a part of my happier memories of childhood.

There was this grand old lady with a gruff voice and a long grey plait called ‘pasha’ a female nawab, I gather, who also took up residence in the hotel for two months every summer in one of the rooms with just one maid-in-waiting or ‘Girl Friday.’ Every evening she would have an armchair put out and sit and smoke beedis as she watched the goings on outside and occasionally called out to a familiar face to come and chit chat with her. I wonder why she was so alone!

Then there was the local college crowd that would visit every afternoon. Girls and boys, who, having given classes a miss, would pass leisure afternoons sitting on the wall of the concrete water tank next to The Only Place restaurant – smoking, chatting, laughing, playing, romancing – all under the tolerant, but watchful eye of Haroon, the owner, himself as he went about his work in and out of the restaurant and the guest house. Of these people, Farhad and Annie stand out as the most popular couple in my memory.

Alice lived in a little cottage behind Regent Guest House. She was an American who had come to India on a visit, fell in love, and stayed back. She introduced me to the wonders of colour on paper. She had this box of 365 (if I remember correctly) Crayola crayons and reams of beautiful white A4 sheets of paper. Whenever I visited her, she would hand me some paper and the colours, and many lovely afternoons were spent at her place drowning myself in the delicious sensation of bringing that white sheet of paper to life with myriad colours. The colours themselves had such wonderful names! I learnt colours I’d never heard of before. Burnt Umber. Mustard. Aquamarine. Whew! And every one of my drawings she would take, and place them carefully in a drawer of her desk. Once she asked me to make a poster for the sale of the fabulously sweet, yellow Japanese watermelons. Even though I didn’t think it was such a good job I had done, she loved it and put it right up!

I remember her asking me to draw a picture of the snake charmer who visited every day to entertain the guests. He had a mongoose, a few cobras, some snake venom antidote and small cloth balls and metal cups with which he’d perform some magic tricks. I drew the scene, and she sent the drawing off to her brother by post. I was no artist, but she validated my amateur efforts and that was just a small part of the lovely person she was. She was the most special and precious part of my childhood days, the sunshine and smiles of my life.

And then, there were the geese. And turkeys. Haroon used to get them for Thanksgiving or Christmas or Easter or whatever. They would, in the meantime, waddle around everywhere, not knowing they belonged to The Only Place. Their favourite place, away from the madding crowd, was our garden. Coming home from school and walking to the back of the house to get in (the back door was always open) was an ordeal for me, because there was this feisty leader of the gaggle of geese who would chase after me trying to nip my ankles with its beak. Ouch! The turkeys were more peaceable and would just gobble away peacefully, looking down their multi-layered chins at me as I passed warily by.

This was a sprinkling of memories from the rosy days of time gone by, of life on Brigade Road, Bangalore, my wonderful city. I think it must love me too, because I live not too far from there even today. Life has taken me to other places, but not for long. I have been pulled back, like a magnet, it seems, to this same area time and again. For which I thank my stars.

Bangalore has changed a lot, but at its heart, it is the same. My beloved. My home. And home, they say, is where the hearth is. Or rather, Heart.

Bangalore Photographer Gajanan Govind Welling took several ‘ethereal’ photos of Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi in the late 1940s. These portraits are known as the “Welling busts.”

Back and forth in time

Deepak Sarma writes for the newspaper The Hindu in 2012.

MacIver Town? Where’s that?” asks Sharath Maney on being quizzed about his neighbourhood. He’s lived on Lavelle Road in the heart of the city for thirty years — that’s all his life — but screws up his face in disbelief when told the answer. MacIver Town, or Shantala Nagar, as it’s now called (not that Sharath’s heard its current name either), envelops portions of the very heart of the city, with Kasturba Road, Lavelle Road and Vittal Mallya Road at its core.

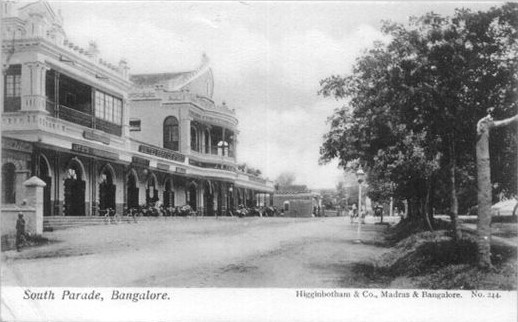

Sharath isn’t the only one who’s never heard of MacIver Town; curiously, many Bangaloreans, have had the same reaction. The area is jinxed on that front: named after L.J. MacIver — who was Collector and president of the Municipal Commission of the Civil and Military Station between 1934 and 1937, and president of Bangalore Club in 1935-36 — MacIver Town has a rather amusing relationship with names. South Parade is now Mahatma Gandhi Road; Sydney Road, Kasturba Road; Grant Road, Vittal Mallya Road and Lavelle Road, M.L. Subbaraju Road, the last never having quite caught on.

Melting pot of cultures

As a BBMP ward, Shantala Nagar encompasses Bangalore’s central business district, and as a neighbourhood, these days, it is associated with a vibrant (and expensive) nightlife. But over half a century ago, and in a different way entirely, it was still an exciting place to be, says M. Bhaktavatsala, who moved to the Cantonment as a student in 1947.

“Jeeps would patrol places like South Parade and Brigade Road to make sure none of the soldiers had sneaked into the bars there.” Basco’s on Brigade Road was a favourite haunt, with ‘Gunboat’ Jack, the African boxer who had fought in World War II, recounting his stories to fellow patrons. “There were so many beautiful Eurasian women — all like Ava Gardner — but they all emigrated,” he says, half-joking.

Preserving the past

Bhaktavatsala, who was the first to contest the proposed demolition of the Attara Kacheri in a PIL in the ’70s, and later fought to preserve Bowring Institute, says he’s done more than anyone else in the city to “save old Bangalore.” He’s also been the president of Bangalore Club, an institution that preserves its colonial architecture and adheres to rules that may seem outdated to some, with its separate gentleman’s bar and dress code. “It’s only followed for its curiosity value, as a mark of tradition,” he says in its defence.

Tiny neighbourhoods

Before MacIver Town transformed into the shopping hub that it now is, it housed a number of tiny neighbourhoods right at its heart. Sophie D’Mello, a retired nurse, lived in a beautiful bungalow on Rest House Crescent Road for around 50 years after she was married in 1952. “You know, foreigners would come to take pictures of my house, and it was even featured in a book,” she says, referring to T.P. Issar’s The City Beautiful. After the house was sold, she says even passing by it was difficult — a block of apartments now stands in its place. While some old colonial-style bungalows still remain in parts of Shantala Nagar, most old houses have gone the way of Sophie’s, replaced by luxury apartments available for no small sum.

Altered landscape

While a walk through Shantala Nagar can serve as a reminder of Bangalore’s colonial past, it also makes apparent the casual attitude of the city’s residents to its history. For better or for worse, commercial buildings now dominate its skyline, having edged out the monkey tops, bay windows and verandahs that characterised many of the older structures.

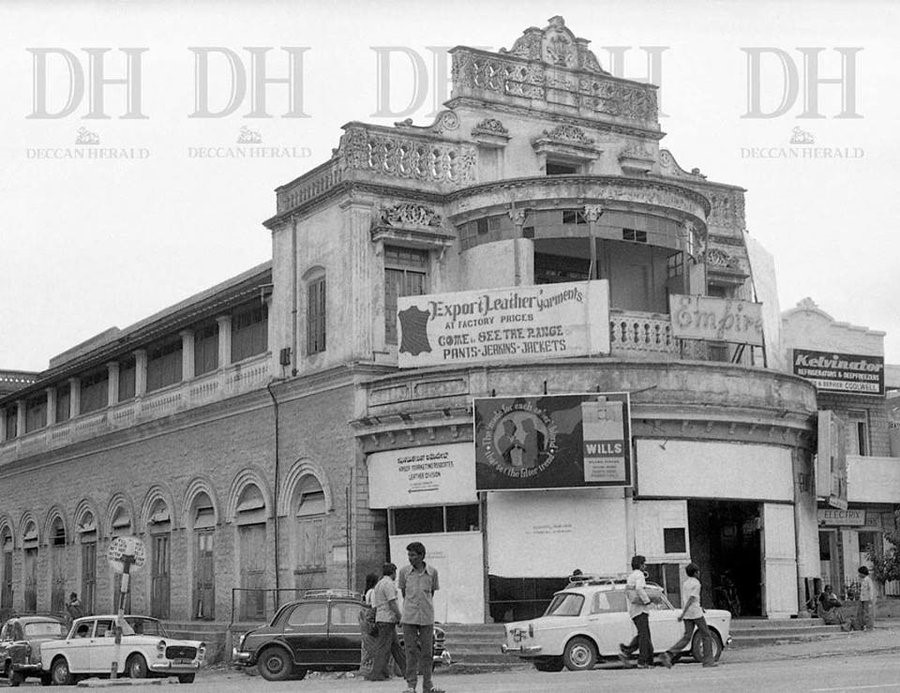

In The City Beautiful, Issar anticipated that many of the buildings featured in his book would soon fall victim to commercialisation, describing a house on Lavelle Road rather poignantly as “a doomed-looking but remarkable ground story bungalow set in a compound as neglected as the building.” Not all of the structures he wrote about in his 1988 book were similarly doomed-looking, but he was right; most of the ones in MacIver Town are gone. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times that today, landmarks such as the theatres ‘Empire’ and ‘New Imperial’ exist only as photographs.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/back-and-forth-in-time/article4191430.ece

Bungalows of the City

Poornima Dasharathi writes in the ‘Deccan Herald’ newspaper (2013).

Janet Pott, the author of Old Bungalows of Bangalore South India, states that the name and the form of the bungalow originated in Bengal. ‘Bangla’ or ‘bangala’ referred to the indigenous Bengali huts of the 17th century.

In Bangalore, bungalows first started to appear in the Cantonment region. The early bungalows were “typical white or cream washed”, describes Elizabeth Stanley in the book, ‘Monkey Tops – Old Buildings in Bangalore Cantonment.’ These bungalows were to the South of Parade Ground, i.e., on St Mark’s Road, Museum Road, Residency Road and Richmond Road.

The structure consisted of a flat-roofed portico with support pillars and behind it a curved verandah. Its size varied, based on the owner’s social stature.

The general basic plan is usually a verandah with support pillars, a living or a drawing room and a dining room in the centre. The bedrooms and dressing rooms open to each side of the living room.

The front of the bungalow was imposing and offset by huge gardens. A servants’ quarter, a stable and other necessities like poultry or a cow shed were present in the backyard. In the leisurely life of the pre-Industrial era, the bungalows sometimes included tennis courts or putting greens. The building, with its stone work, balustrades marking roof levels and imposing look contributed to the ‘classical’ look, she concludes.

An example of the classic bungalow is the Raj Bhavan, which was once the home of Sir Mark Cubbon, the Commissioner of Mysore (1834-1860). Raj Bhavan is out of bounds for visitors and there aren’t many bungalows of its kind left to look at. But I had some luck. Maureen MacDonald, who recently visited the City, shared a picture postcard of her grandfather and his home in the City in the 1850s.

A typical white bungalow with flat roof, it looks straight out of the Victorian era — spacious home, horse carriages, the burra sahib, ladies in long white gowns and hats and children in their European dresses. But she did not know the address and hence we don’t know its current avatar. For her and many others, these homes live in memories.

Monkey tops

By the early 20th century, the fashion of classical buildings gave way to ornamental buildings that were taller and had high-pitched roofs. The flat roofs were now pyramidical and tiled; the balustrades gave way to battlements, towers with high-pitched roof and bastions. The most important change was the pointed roof for the windows called the ‘monkey tops’. These lovely pointy wooden roofs can still be seen in the few bungalows or even old public buildings that still exist today.

As I walk across into Usha Kumar’s home, the first thing I notice is the beautiful monkey tops that decorate the front windows. Though the wooden trellis work of the front door was beautiful, it’s the patterned sunlight falling in the living room that made me truly appreciate the architect’s plan.

Homes, in those days, looked good from the outside as well as the inside. The verandah is covered. But the high-pitched roofs, the high ventilators, the single storey are reminders of the erstwhile ‘bangala.’

Though the bungalow is European, the name is very Indian. Usha has named it after her parents. There is a tulsi plant at the entrance. This cultural contrast comes up in many anecdotes and conversations with her which I find charming.

The Cantonment was, and is, a very multicultural place, informs Mona, the curator of ‘aPaulogy’, artist Paul Fernandes’ gallery on the Bangalore of the 60s and 70s. She recalls her neighbours were a mix of different communities.

Though culturally diverse, there was always harmony and co-existence, she declares. The illustrations in the gallery do illustrate this fact.

https://www.deccanherald.com/content/323131/where-time-stands-still.html

Old Bungalows In Bangalore by Janet Pott (1977)

Download:

https://archive.org/details/old-bungalows-in-bangalore-janet-pott

Retracing the Colonial Roots of Bungalow Architecture in Bangalore

Download:

https://www.ijera.com/papers/vol10no6/Series-7/F1006073748.pdf

The Colonial Bungalow in India

Bengaluru: Carpenter Gothic Bungalows. Bengaluru was the largest military cantonment town of the British Raj in Southern India and was part of the Madras Presidency region. It was founded in the early nineteenth century; later the town flourished as a military station as well as an administrative and residential centre. Around 1883, the cantonment was enlarged by the addition of Richmond Town, Benson Town and Cleveland Town where a number of bungalows were built for military officers or for retired Britons. Many bungalow designs in Bengaluru were inspired by what was going on in Europe and the Americas, as the Carpenter Gothic style began to influence public buildings and institutions there. From the 1880s to the 1930s these bungalows became taller and assumed a Romantic expression, with steeply pitched roofs whether or not they were required for climatic reasons. Most examples possessed symmetrical plans that invariably had a central hall. The facades received maximum attention. Cast iron were used for railings, brackets and pillars. The porches of the bungalows were prominent with sloping roofs and fretwork infill. Gradually, the Carpenter Gothic style was adapted by the locals as the town grew. The Bengaluru Monkey-Tops, as the bungalows are popularly known, are a record of not just socio-cultural but also craft history which is unique to the region. With the rapid growth in the twenty-first century of Bengaluru as the Silicon Valley of India, these fine examples are threatened by real estate speculation and city redevelopment plans as urban land prices soar.

Download:

https://www.iias.asia/sites/default/files/nwl_article/2019-05/IIAS_NL57_2627.pdf

Bangalore Guide-book from 1963

1963 Guide-book of Bangalore

Download:

https://rarebooksocietyofindia.org/book_archive/196174216674_10153799236041675.pdf

Guide to Bangalore from October 1956

1956 Guide to Bangalore

Download:

https://ia902807.us.archive.org/9/items/unset0000unse_i1x0/unset0000unse_i1x0.pdf

BANGALORE GUIDE An Indispensable Handbook

MG Road, Bangalore