Series: Westerners in India.

The following is an expanded and more compressive article that is sourced from Ashrams of India Volume 2.

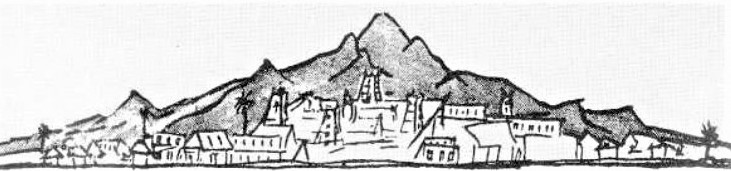

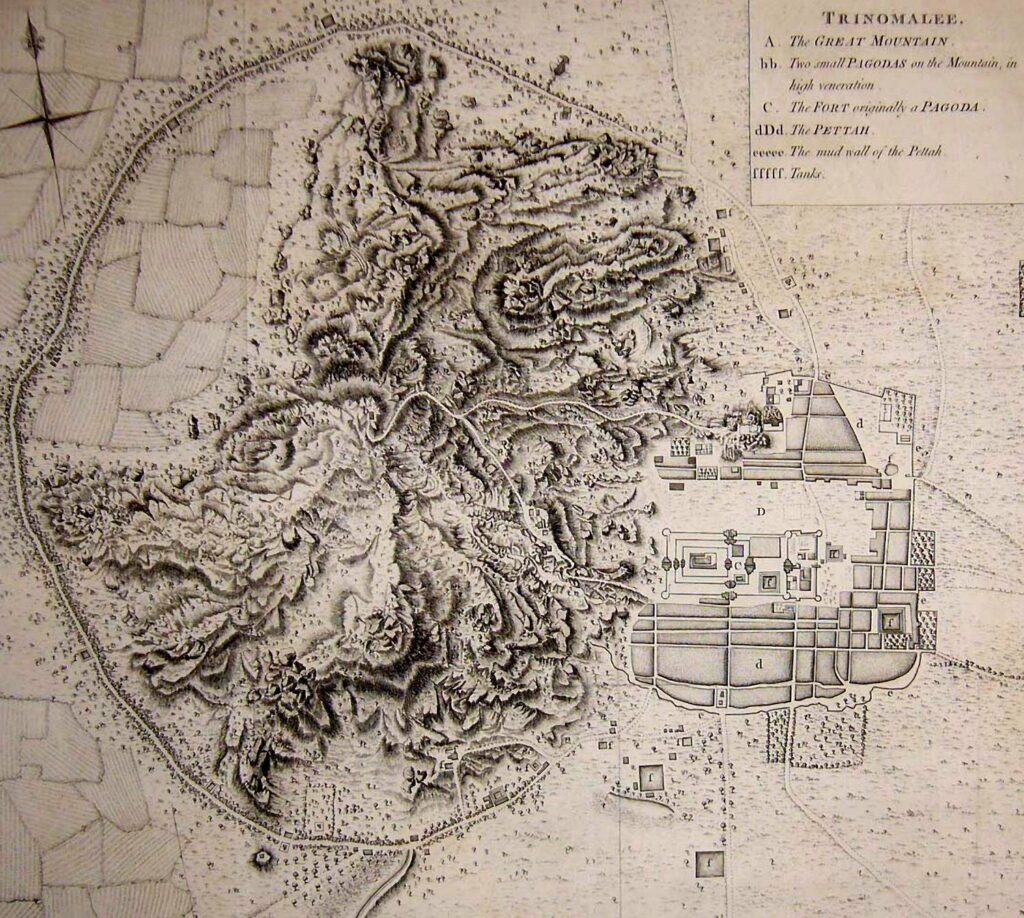

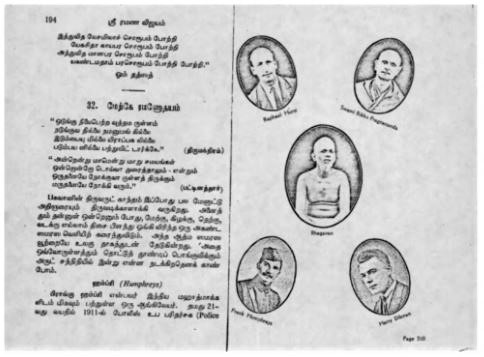

In 1911, Frank Humphreys, a policeman stationed in India, became the first Westerner to discover Sri Ramana. He wrote articles about him which were first published in The International Psychic Gazette in 1913.

Sri Ramana only became relatively well known in and out of India after the publication of two books in 1934 and 1935 by Paul Brunton, who had first visited him in January 1931 along with Bhikshu Prajnananda (former military officer Frederick Fletcher known later as Swami Prajnananda).

Some of the other foreign visitors that followed included Maud Alice Piggot who in January 1935 is thought to be the first English lady to visit Sri Ramana,

American social psychologist, Professor Pryns Hopkins (Prynce Hopkins) visited Sri Ramana after reading about him in Paul Brunton’s A Search in Secret India,

Grant Duff (Douglas Ainslie 1865 – 1948) was a Scottish poet, translator, critic and diplomat born in Paris, France, visited in 1935,

American anthropologist and writer Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz in 1935,

American Chemist Dr Bernhard Bey in 1935,

Paramahansa Yogananda (accompanied by his secretaries Richard Wright and Ettie Bletsch) in November 1935,

Maurice Frydman, a Polish-Jewish devotee who was a research engineer working in Bangalore was a frequent visitor from 1935,

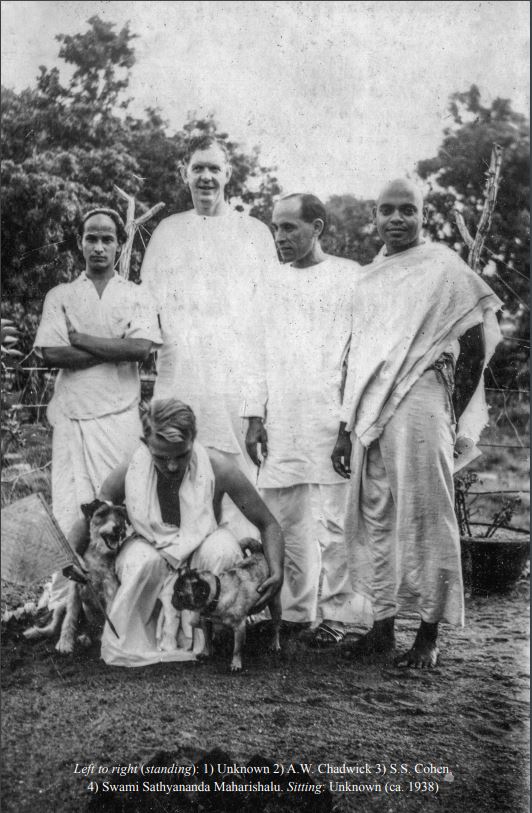

Major A.W. Chadwick in November 1935,

Hans-Hasso Ludolf Martin von Veltheim-Ostrau in December 1935,

English Poet Lewis Thompson in approximately 1935 and stayed for 7 years,

Polish writer Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) lived in India from 1935 until her death in 1971 visited often,

American spiritual writer, author of the spiritual book series Life and Teaching of the Masters of the Far East, Baird T. Spalding (1872 – 1953) with a party of tourists that included the American couple Mr and Mrs Taylor in 1935 or 36,

S.S. Cohen, an Iraqi Jew, who made Ramanasramam his home in 1936,

American Dr Henry Hand in 1936,

American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger visited in January 1936,

There were some French ladies and gentlemen and American as visitors to the Asramam in January 1936,

33 year old Dutchman Sadhu Ekarasa (Dr G.H. Mees) came in 1936, (he mentored Hildegard Elsberg, a German Jew who lived in India for 10 years from 1937, teaching at a convent school in Kodaikanal – it is not known when she first arrived in the ashram but is thought to be 1937/38),

Olivier Lacombe (L’Attache Culturel, Consulat General de France, Calcutta) was a French doctor of philosophy who came for darshan in May 1936,

British scholar and Theosophist Duncan Greenlees, came in October 1936 for a few days,

French Dr Suzanne Alexandra Curtil Sen (Sujata Sen) in December 1936,

Pascaline Mallet visits in December 1936, a French writer and seeker whose 1938 book Turn Eastwards details her nine-month pilgrimage in India from December 1936 to September 1937,

Alfred Julius Emmanual Sorensen (Sunyata) was a Danish devotee made the first of four trips to Ramana in 1936,

American Mrs Roorna Jennings of the International Peace League, January 1937,

Professor Banning Richardson arrived in May 1937 and stayed for three days,

Swiss author Lizelle Reymond and future husband Jean Herbert in 1937,

David MacIver in 1938,

American engineer Guy Hague arrived in Sri Ramanasramam in 1938 after travelling the world, he stayed 2½ years,

Christina Austin brought Somerset Maugham (and his companion Gerald Haxton ?) to the ashram in January 1938 for a few hours (his 1944 novel The Razor’s Edge models its spiritual guru after Sri Ramana),

Three ladies on a short visit in Feburary 1938, Mrs Hearst from New Zealand, Mrs Craig and Mrs Allison from London,

A young English woman, identified as Miss J, arrived in May 1938, dressed in a Muslim sari, she had evidently been in North India and met Dr. G. H. Mees,

An American gentleman, Mr J. M. Lorey in June 1938,

Cuban-American writer of the 1920s and 30s Mercedes de Acosta stayed for three days in 1938,

renowned American painter Eliot C. Clark visited in 1938,

from Morocco, Bernard Duval in 1938 for about 15 days,

Two ladies, one Swiss and the other French, visited Maharshi in December 1938,

English woman Miss Ward-Jackson 1938/39,

Eleanor Pauline Noye arrived in 1939 and stayed for 10 months,

Ethel Merston visited in 1939,

Ella Maillart was a Swiss travel writer and photographer who remained in India from 1939 to 1945 and resided mostly in Tiruvannamalai,

William S. Spaulding Jr of New York City visited Sri Ramana in the 1930s,

Mother of Dr Suzanne Alexandra Curtil Sen, Jeanne Curtil and Suzannes’s daughter Monica arrived in 1940, Monica would attend school in Bangalore but would visit the ashram once or twice a year until 1952,

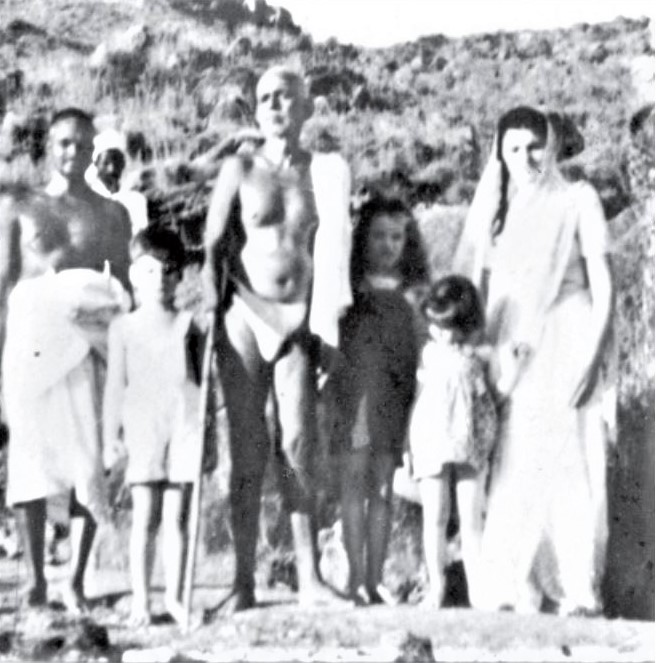

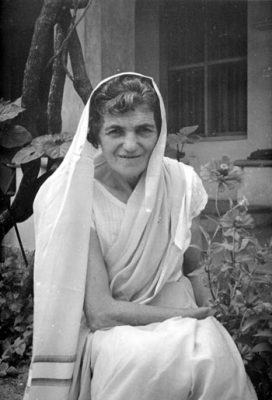

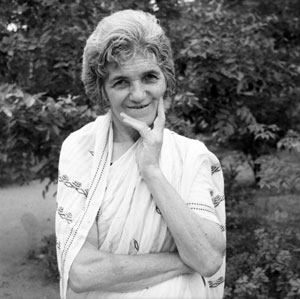

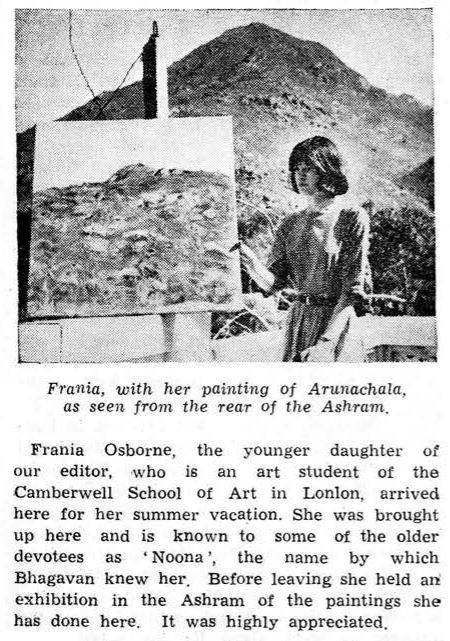

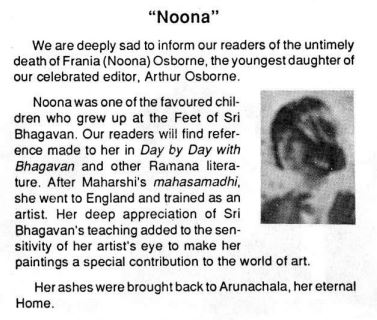

Lucia Osborne with her children Catherine, Frania and Adam, arrived in 1942,

Blanca Schlamm (Atmananda), an Austrian concert pianist in 1942,

William Samuel stayed and sat in the silence with Ramana Maharshi for 14 days in April 1944,

Alexander Phipps (Madhava Ashish) visited in 1944,

Australian travel writer Frank Clune visited in 1944,

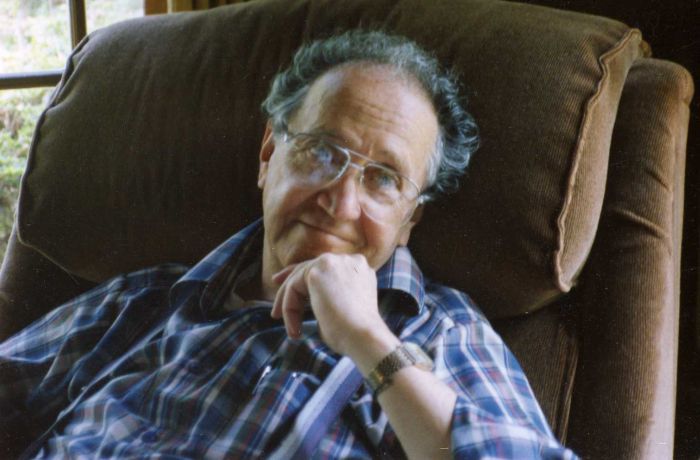

Arthur Osborne in 1945,

Osborne’s fellow POW, Dutchman, Louis Hartz would visit after the Second World War,

Georges Le Bot, Private Secretary to the Governor of Pondicherry, and Chief of Cabinet of the French Government visited in December 1945,

British teacher Mr Phillips who was a former missionary and had been in Hyderabad for about 20 years visited in May 1946,

European Mr Evelyn in May 1946,

Mrs Barwell (whose husband was a barrister in Almora), accompanied by Australian Miss Eleanor Harriet Rivett, principal of the Women’s Christian College in Madras, visited in September 1946,

Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) arrived with a party of 25 Polish people, mostly girls in October 1946,

Miss Boman, a Swiss lady who had been in India for about eight years, and was head of the Baroda palace staff of servants, stayed for 4 days in October 1946,

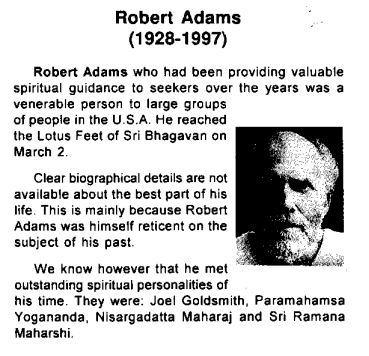

American Robert Adams also stayed for three years from 1947 (disputed as to whether he was ever at the ashram),

Swiss Henri Hartung first came in 1947 for ten days,

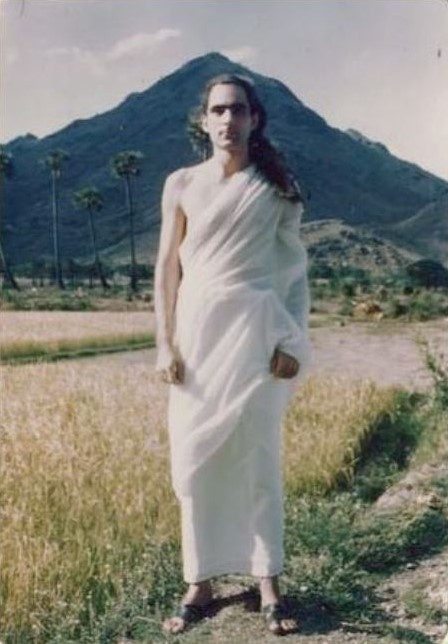

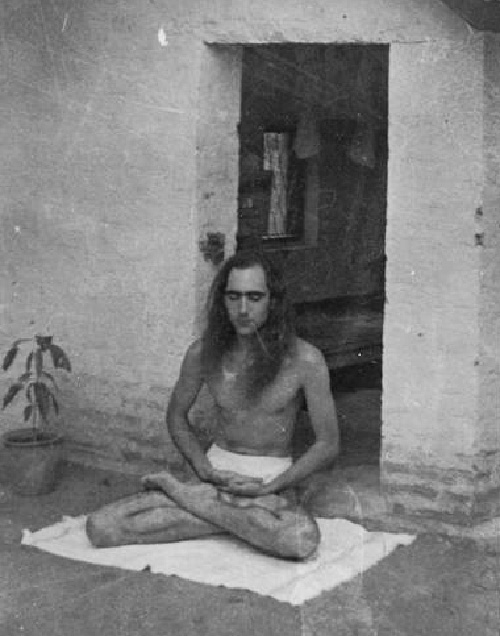

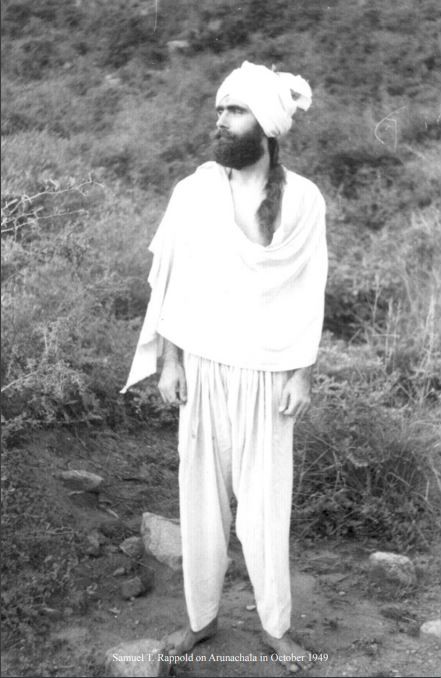

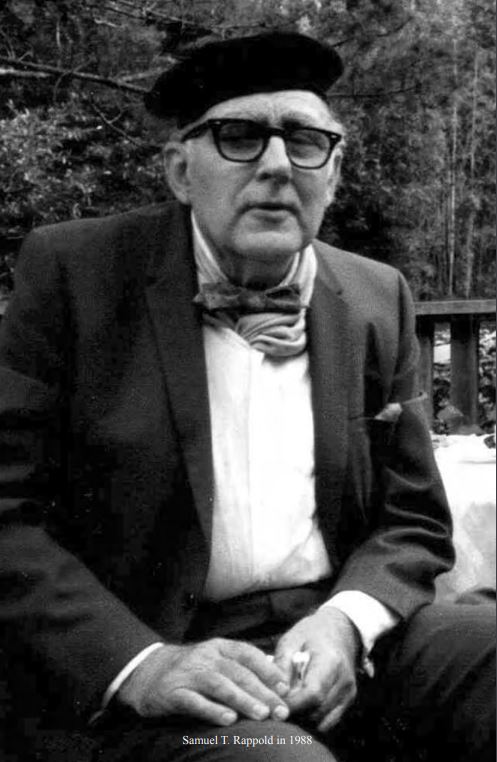

American Sam Rappold arrived on the 27th of December, 1947,

Elsa Lowenstern is mentioned in Thelma Rappold’s 1948 diary entry,

a French sannyasin is also mentioned in the same diary who came for Bhagavan’s darshan, leaving France four months previously without any money, stowing away on a French ship bound for India. Barefoot and with nothing to call his own but the clothes on his back, he was making a pilgrimage through India in search of spirituality,

American Thelma Benn (later Rappold) spent nearly three years with Ramana Maharshi from February 1948 until Summer 1950 (her husband Sam Rappold was there for most of this time – these two Americans arrived in India independently, they married in Varanasi before leaving India), her friend from Seattle Mrs Wally Groeger visited her in the ashram in December 1948 and stayed for nearly a year, before going on to meet Swami Ramdas and then later returning to the States,

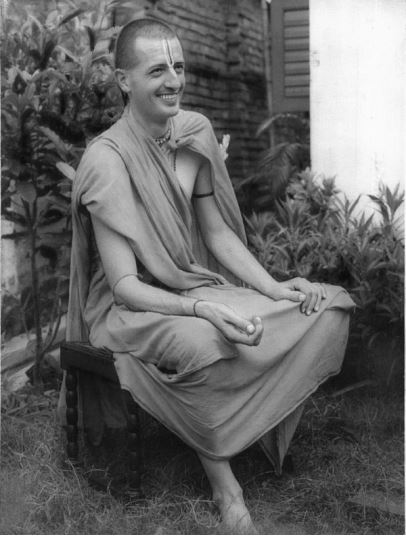

British national Sangharakshita (Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood) and his Indian friend Buddharakshita arrived in late November 1948, and stayed for six weeks,

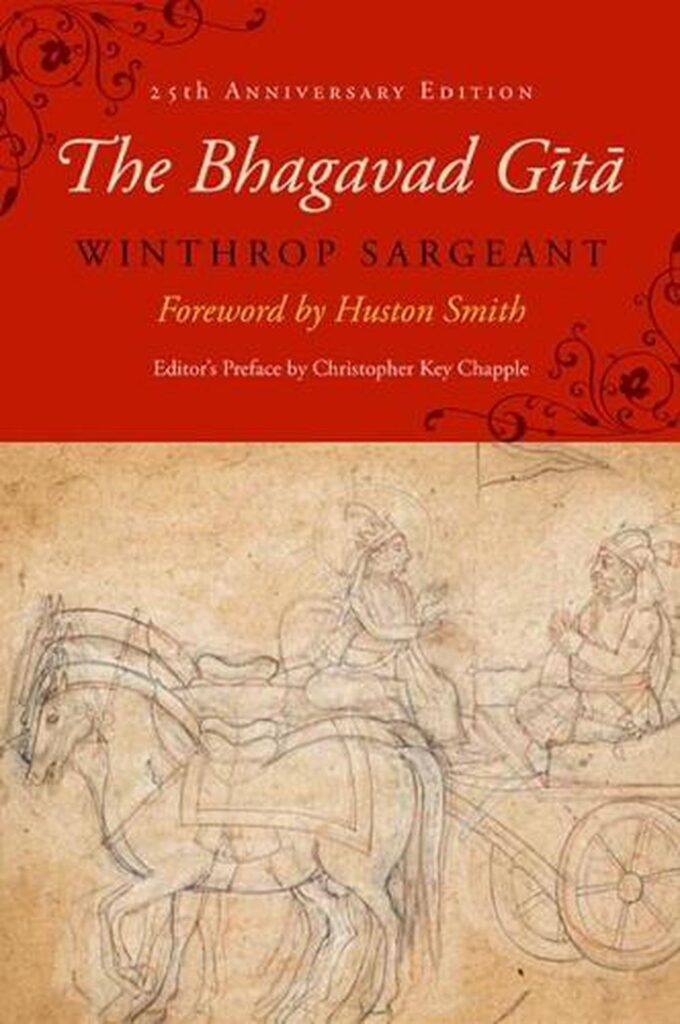

American journalist Winthrop Sargeant arrived in 1948 for the Life Magazine article published in 1949,

American Photographer Eliot Elisofon spent two weeks on the ashram in 1948 taking the photos for Life Magazine that were published in 1949 (he made several trips to the ashram),

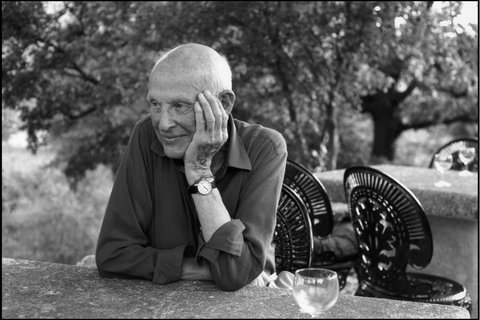

French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson first visited in 1948, and later in 1950, arriving 10 days before the Maharshi’s mahasamadhi,

Krishna Prem (Ronald Nixon) met Ramana Maharshi in 1948,

two English women from South Africa Gertrude de Kock and Eureka Wessels arrived in 1948 staying for 10 days,

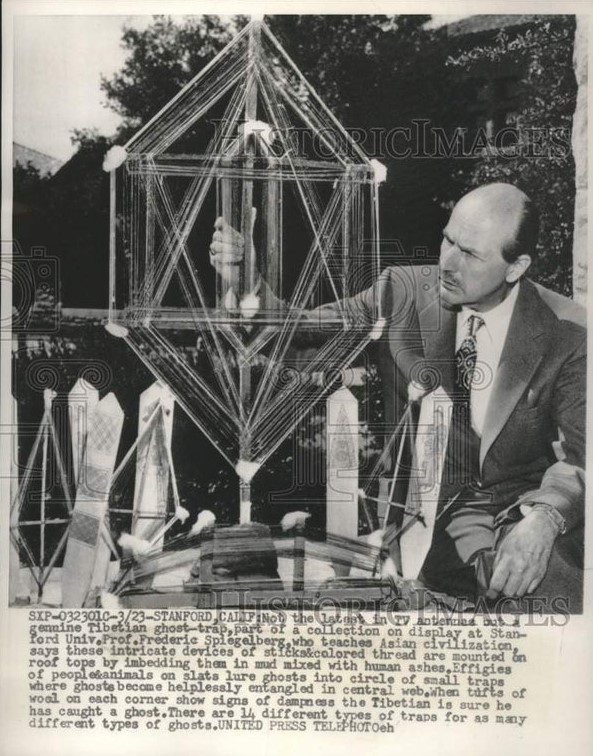

Stanford University professor Frederic Spiegelberg visited Ramana Maharshi sometime between 1948 and 1949,

friends of Eleanor Pauline Noye, Melva Cliff and Ananda Jennings were at the ashram for some weeks in 1949,

Swede Peer Wertin / Per Westin (Swami Ramanagiri) in 1949 and in 1950,

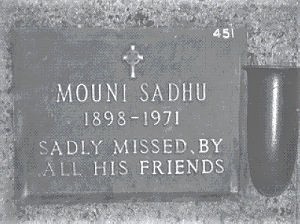

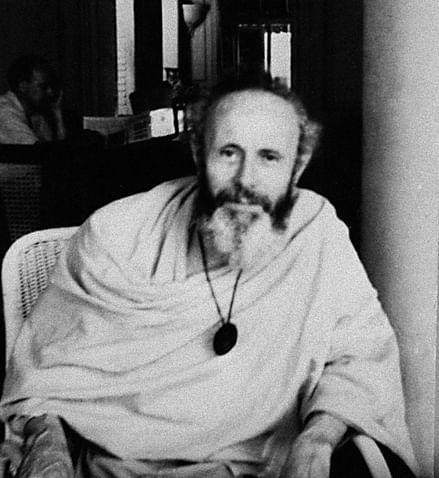

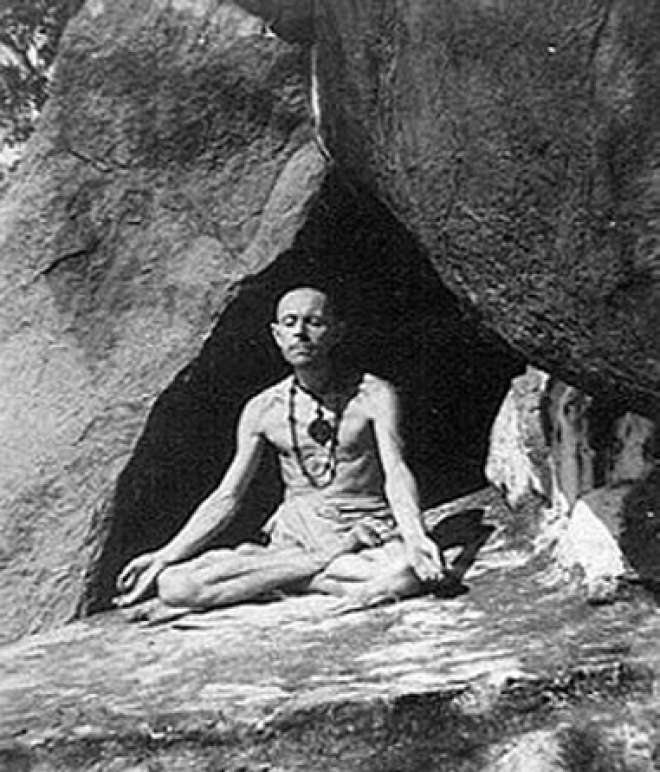

Mieczyslaw Demetriusz Sudowski (Mouni Sadhu) Polish author of spiritual, mystical and esoteric subjects in 1949 for a few months,

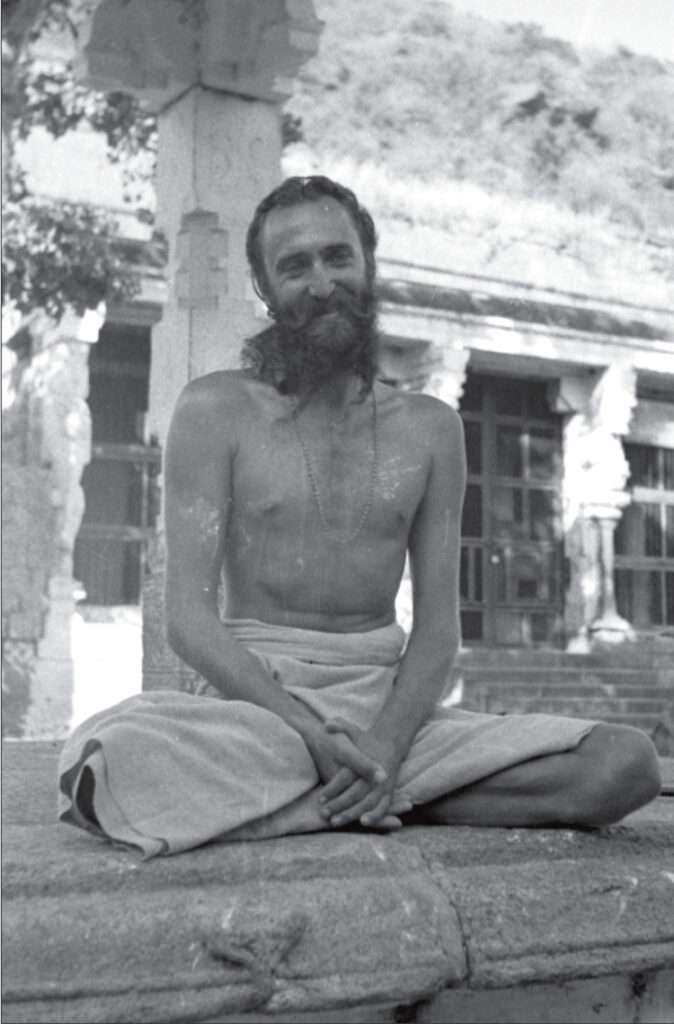

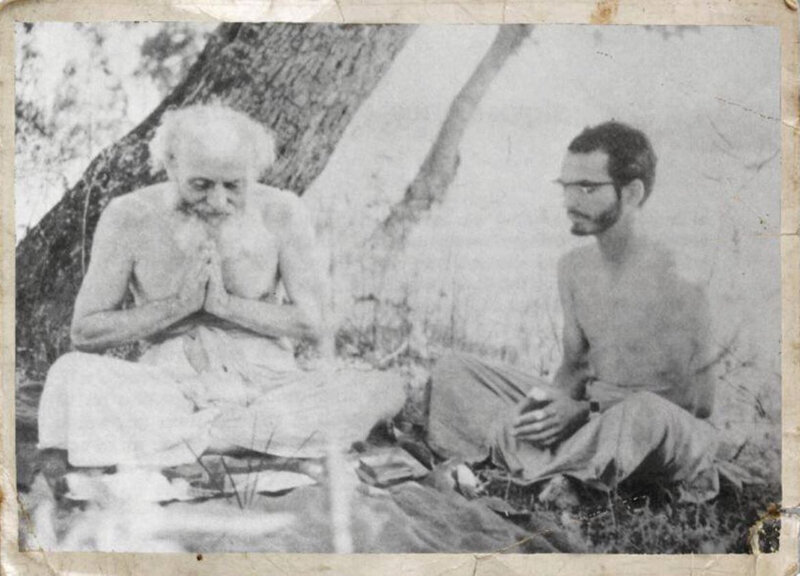

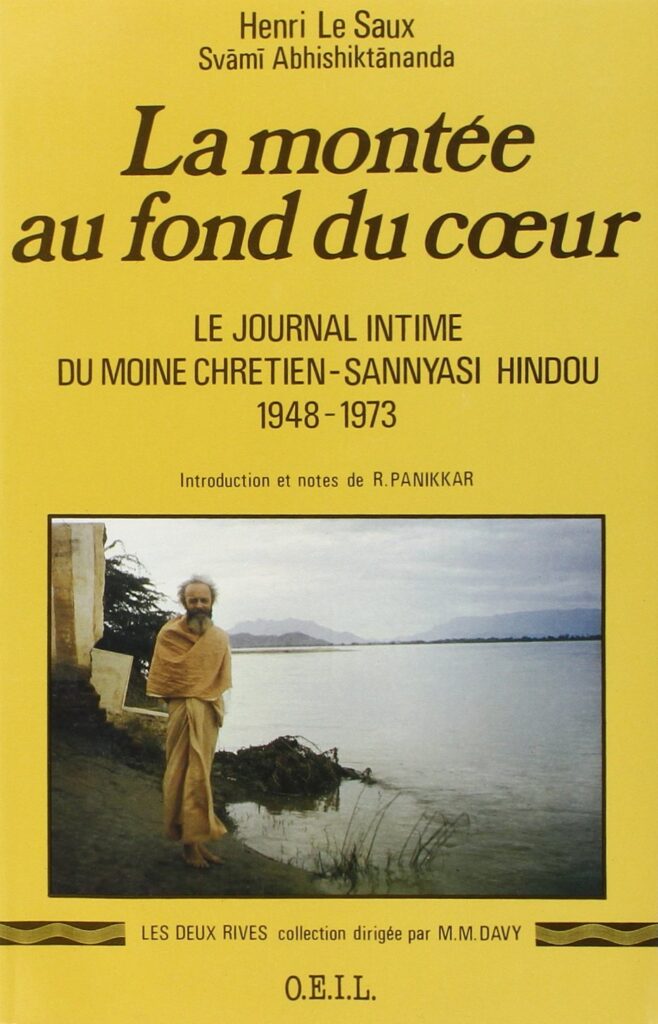

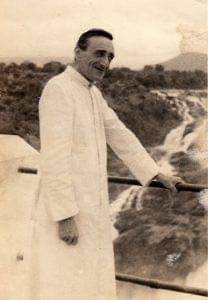

Henri Le Saux (Swami Abhishiktananda) first visited the ashram in January 1949 along with Fr. Jules Monchanin (Parama Arubi Ananda) who was on his third visit,

Dutch teacher and writer Wolter A. Keers was taken to Ramanasramam in 1950 by Roda Maclver, wife of David MacIver,

Miss Eleonore de Lavandeyra in 1950,

American yogini Judith Tyberg (Jyotipriya) stayed for a week sometime between 1947 and 1950.

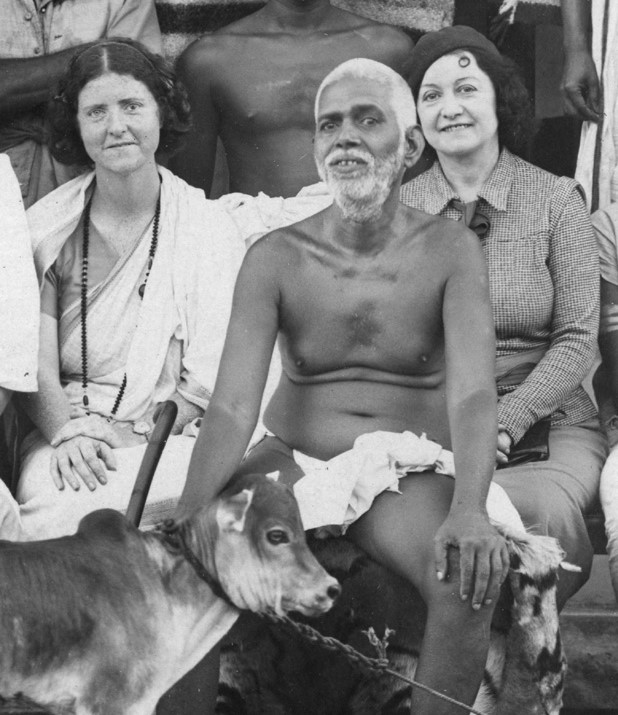

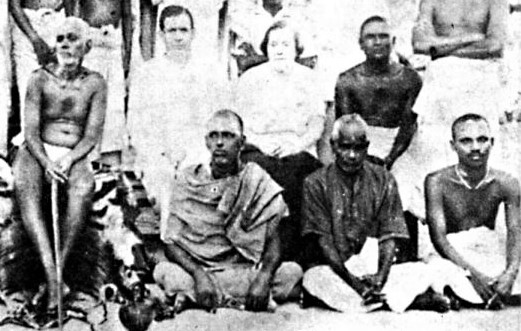

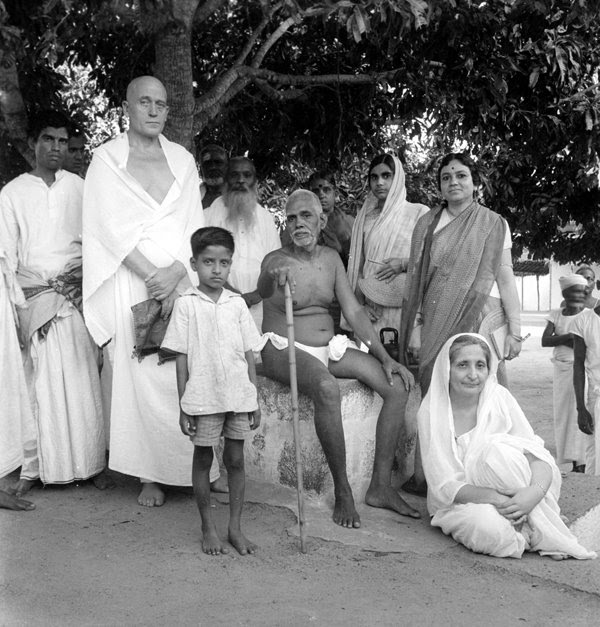

Unidentified Western visitors and devotees of Ramana Maharshi at the end of the article.

https://archive.arunachala.org/ramana/devotees

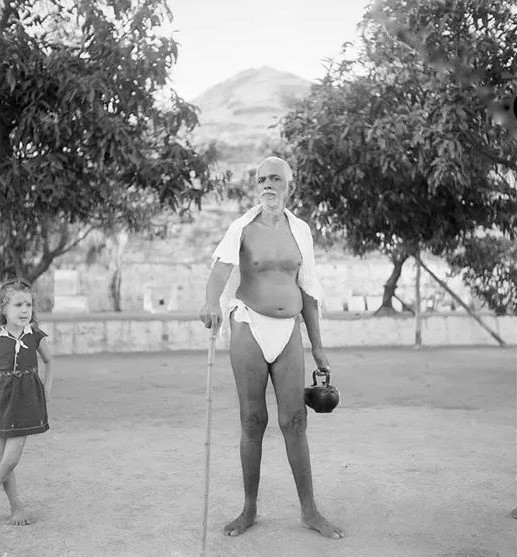

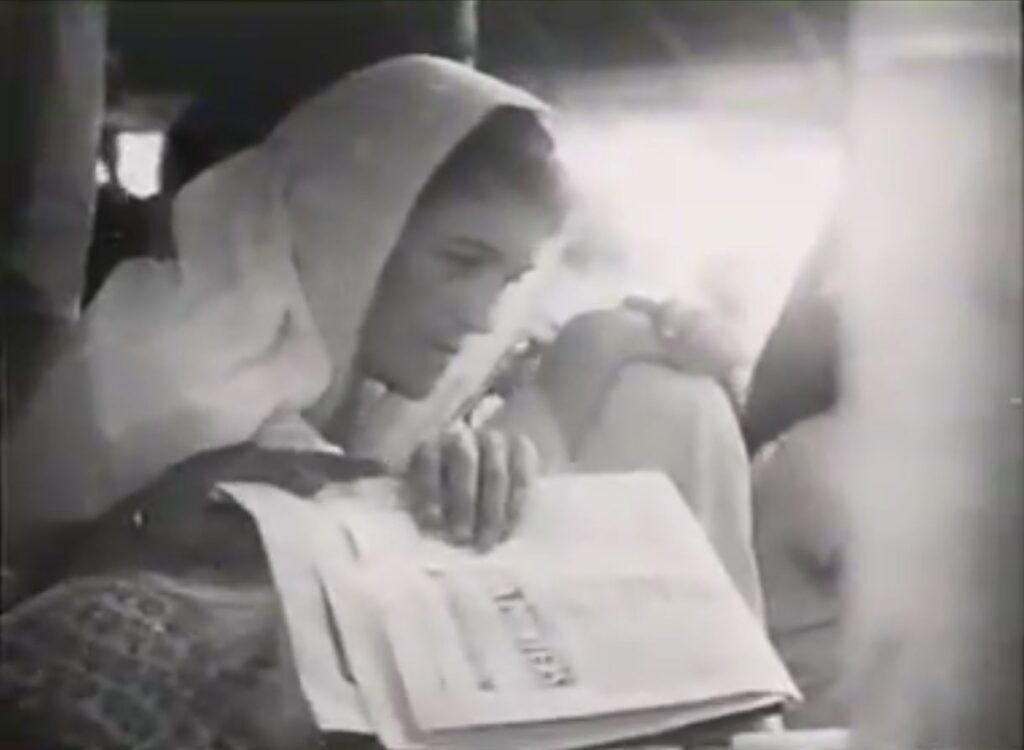

Lucia Osborne with her children Catherine (Katya, Kitty) Frania and Adam, arrived in 1942.

During a summer holiday in Kashmir during 1942, the Osborne family were met by David MacIver who also owned a cottage opposite Ramanasramam. After a few weeks, Osborne had to return to Bangkok, Lucia and the three children went with McIver to Tiruvannamalai. Parting at the Lahore railway station, Lucia and the children went on to Bombay and then south, and Arthur went to Calcutta and then on to Thailand. Returning to Bangkok he was taken as a POW and held for three and a half years by the Japanese. Osborne arrived in Ramanasramam in 1945, following his internment to be reunited with his family.

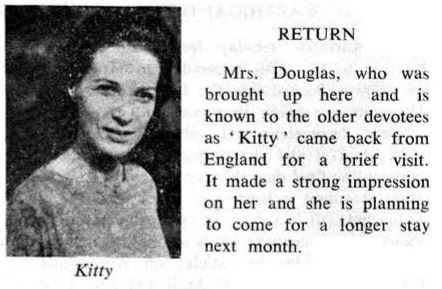

Kitty Osborne writes in 2018 – My mother, Lucia Osborne, was born in Poland as Ludka Lipszyc on February 15, 1904. She came from a large orthodox Jewish family and met my father, Arthur Osborne, when he was in Warsaw teaching English. At the time, she was engaged to a very rich Jewish boy from Czech Republic, but from what I found over the years my mother looked at my future father once and made a decision. She knew what was good for her… and for him! They married in 1934, I was born in 1936, and two years later we went to England. Her family was not interested in marriage, they seriously threatened to renounce her, but she had never been a pushover … not then or at any other point in the future, she was just like that. When Lucia and her husband came to Yorkshire and met his family, it turned out that that this family wasn’t too happy about it either. “What, did you marry a Jewish woman ?! What a shame, ”etc. I was only two years old at the time, so I had no real memories of these events, but I picked up a lot of the emotional background by eavesdropping on adults talking, as children do when they grow up – they don’t realize they are listening.

Nevertheless, my parents sensed problems with the political climate at the time, so my father applied for a job as a lecturer at Chulalonghorn University in Thailand, then known as Siam.

They both wrote many letters and tried very hard to get Lucia’s family to join them, but the family did not seem to be concerned about Germany and Nazism at all. Then the borders were closed and no one was allowed to leave Poland. After the war, it turned out that my mother’s entire family, except for one sister and one brother out of ten siblings, had been murdered in various concentration camps. For the rest of her life, my mother could barely talk about it.

In Bangkok, we lived in a vast old house surrounded by an overgrown old garden. My brother Adam and my sister Frania were born there, and my memories, though somewhat blurred by time, show a happy and somewhat wild childhood. Adam and I spoke mostly Siamese and not English because it is a tonal language and it is much easier for children to learn it.

Although I did not realize it, my parents were already involved in the search for a guru who could show them a deeper meaning in life. In the 1940s and 1950s, spiritual ignorance and intolerance were much stronger than they are today, and the search for a deeper lifestyle was quite unusual. A small team of like-minded seekers formed a group that stayed in touch for many years and shared information.

The turning point on my parents’ spiritual path was 1936, the year of my birth. They met Martin Lings, who later was the private secretary of Rene Guenon, a leading thinker in the school of Eternal Philosophy. Rene Guenon said that there are universal truths and wisdom common to all major world religions. Inspired by this, my parents went to Switzerland the following year and met Frithjof Schuon, who initiated them in Sufi Shadhiliya-Alawiya. Lucy was given the Arabic name Shakina. Later, my father translated Guenon’s work, The Crisis of the Modern World, into English. About the same time, one of their group of seekers heard about Ramana Maharshi and came to Tiruvannamalai to investigate the matter, but [one of the group members] announced that Ramana was not a guru.

In 1941, my father took a long vacation from Bangkok. His university used a unified system for workers abroad – two years of work followed by six months of vacation, to give them time to visit their home country and return by boat. My parents were not interested in returning to England, so they went to Kashmir to meet the great Sufi master. During this trip, my father received a telegram telling him that the situation in Bangkok is very precarious and that he should not bring his family back until things are more settled. He returned on his own, promising to bring us back as soon as he could. Two days after his return, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour. They, too, marched to Siam and all the foreigners – including my father – were interned. Arthur was imprisoned in a POW camp on university grounds, which was under the direct supervision of the Siamese. He later claimed that this was the reason he survived, as many people under direct Japanese control were sent to work on Burma’s railroads. Most of these people did not survive.

Lucia found herself alone, without funds and with three small children: five, two and one year old. One of the aforementioned group of spiritual seekers, David MacIver, travelled to Tiruvannamalai, met Ramana Maharishi and was so impressed that he bought some land there and built a house. David lived in Mumbai working for The Illustrated Weekly of India, so he spent very little time in his house and gave it to my mother until she could manage and hire her own. Thus we came to Tiruvannamalai and Bhagavan.

When Lucia met Ramana Maharishi, she realized that whoever told them that He was not a guru was completely wrong. Not only was he a guru, there was also a Sat Guru; he was the greatest living embodiment of Divinity. She immediately wrote to Arthur and told him about it, but he did not receive any letters from his family for two years. We three children immediately accepted that Bhagavan was extraordinary. As far as I can remember, we never talked about it or thought about it… we just knew it was so. We talked with Bhagavan, showed Him our toys. We told Him our stories and He always responded to us on a level we understood. I remember that my mother spoke to him (through an interpreter) – usually she wanted to clarify some metaphysical problem that we were not interested in. People often said that Bhagavan’s answer to one person’s question can also solve the unwritten questions of others present. Much of what he said was specific to the person to whom he was addressing, but the answers also interested others. People even enjoyed comments about our strollers and reading books. I showed Him my nursery rhyme book, Mother Goose, and he noticed how worn it was, and then gave it to someone to rebind. Actually, now I think we remember showing everything to Bhagavan: letters, newspapers, sharing stories about our friends and families. The old hall was a fairly open and friendly place with local gossip as well as more serious conversations about spiritual quests. what he said was specific to the person to whom he was addressing, but the answers also interested others. People even enjoyed comments about our strollers and reading books. I showed Him my nursery rhyme book, Mother Goose, and he noticed how worn it was, and then gave it to someone to rebind. Actually, now I think we remember showing everything to Bhagavan: letters, newspapers, sharing stories about our friends and families. The old hall was a fairly open and friendly place with local gossip as well as more serious conversations about spiritual quests. what he said was specific to the person to whom he was addressing, but the answers also interested others. People even enjoyed comments about our strollers and reading books. I showed Him my nursery rhyme book, Mother Goose, and he noticed how worn it was, and then gave it to someone to rebind. Actually, now I think we remember showing everything to Bhagavan: letters, newspapers, sharing stories about our friends and families. The old hall was a fairly open and friendly place with local gossip as well as more serious conversations about spiritual quests. I showed Him my nursery rhyme book, Mother Goose, and he noticed how worn it was, and then gave it to someone to rebind. Actually, now I think we remember showing everything to Bhagavan: letters, newspapers, sharing stories about our friends and families. The old hall was a fairly open and friendly place with local gossip as well as more serious conversations about spiritual quests. I showed Him my nursery rhyme book, Mother Goose, and he noticed how worn it was, and then gave it to someone to rebind. Actually, now I think we remember showing everything to Bhagavan: letters, newspapers, sharing stories about our friends and families. The old hall was a fairly open and friendly place with local gossip as well as more serious conversations about spiritual quests.

Once we got to Tiruvannamalai by train from Madras. I called a horse-drawn carriage with a nice, sturdy horse to take us home. But my mother said, “No, we’ll take that horse-drawn carriage with a skinny, hopeless looking animal.” I said she was not fit, but my mother insisted, “If we don’t hire this animal, no one else will take advantage of it and then it will starve.” Indeed, that horse had died before we got to the station gate!

Lucia was a wonderful woman. She managed to create a home, feed, dress and raise her children in terrifyingly difficult circumstances. Ultimately, the British government granted her a pension which was issued as a loan during the war. It was some help, but it is interesting that her husband, my father, insisted on paying off his retirement in small sums after the war, despite the fact that my mother, who dealt with our family’s finances and was aware of our difficulties, noted a bit reluctantly, that Arthur was probably the only internee to ever pay that debt.

Lucia became one of Bhagavan’s most ardent and zealous devotees. She spent as much time as possible meditating in His presence in the Old Hall. My brother Adam once went to Bhagavan and told him that his daddy was in a concentration camp and would like Bhagavan to take care of him and keep him safe. Bhagavan smiled and nodded. It was enough for all of us. We knew our daddy would be safe and my mother stopped worrying.

We three children learned Tamil the way children do, but for Lucia it was much more difficult. The main problem was that written Tamil is completely different from spoken Tamil, and in those days there were no books to learn spoken Tamil! So my mother spoke a combination of the classical Tamil she had learned and the street, rough Tamil. We children laughed and teased her about it. I don’t think we realized that she already spoke seven languages anyway, but we probably wouldn’t have been more impressed even if we had known it; languages come so easily to children!

Once upon a time we were all in Madras with friends named Sharma. There, Lucia received a telegram saying that Arthur Osborne was dead – he was killed during the war. Her friend, Mrs. Sharma, immediately began to feel sorry for the mother of the loss, but Lucy was not interested in her comforts. “He’s not dead,” she assured her friend. “If he was dead, I would know it. In any case, Bhagavan said he would take care of Arthur. He’s not dead. Then a very peculiar scene happened in which Mrs. Sharma was still trying to comfort her mother by trying to confront the facts while my mother was consoling Mrs. Sharma who thought that Lucy had lost her mind in grief. In any case, it was all clear up in a few days, when Lucia received another telegram saying, “Sorry, that’s not the Osborne.” Interestingly, none of us even doubted that our father was safe. After all, Bhagavan has made it clear.

Lucia loved to walk around Mount Arunachala, the holy manifestation of Shiva on earth. I think she walked once a week. One time she went to pray for my father’s health because he was sick for a while. She was so engrossed in her thoughts that she passed right next to the entrance to our path. Instead of going in the opposite direction during pradakshina, she continued walking and circled the mountain twice in a row! Other times she was walking, it was raining, or rather heavy downpour. Being quite close to one of the mantapamas standing on the hill, she threw herself there and sought shelter. Unfortunately, the mantapam was very old, as are most, and leaked very heavily. Finally she pressed herself from behind into a small temple built for a deity and sat down to wait out the rain. Some of the villagers followed her in because they, too, wanted to avoid the downpour. My mother usually wore white saris, and when she moved a little in her recess there was an immediate panic and people shouted “pissasu, pissasu” which means “spirit, spirit”. The best thing happened when several people came to us the next day and told my mother to be careful when walking around the mountain, as there is a ghost lurking in the mantapama and it could attack her.

As the eldest of the three Osborne children, I should have understood some of the extraordinary difficulties my mother had to grapple with, but I must admit that I had no idea. Lucia somehow made our life carefree and fun, and we had time to run wild around the area. I don’t remember ever feeling poor or deprived of anything. She also managed to save some money and buy a piece of land, admittedly very cheap, on which she built a house for us after my father returned from the camp. She once told me that the whole house only cost 5,000 rupees. My mother never threw anything away. It has always been used for pieces of rusting metal, pieces of cracked cans… whatever you find. One time she broke her leg and was completely immobilized. I took advantage of it and threw myself into the old warehouse. I got rid of piles of rotten, rusty springs and completely dilapidated electric stoves… in fact, we found a huge pile of scrap metal. I threw all these things in the garden and told Unnamalai to get rid of it. When I returned a few months later, the first thing I saw in the garden was the same pile of rubbish. “Why?” – I asked. “I told you to throw out all this trash.”

It was made clear to me quite clearly that when Amma’s health improved and she started walking again, she immediately wanted to know what happened to her pile of trash, and no one was prepared for her anger, telling her they had been thrown away. She would have kept it there forever if I hadn’t picked up the garbage myself and disposed of it.

Unnamalai accidentally came to see my mother when she was about 16 and a leper. My mother had a reputation as a homeopathic doctor, and Unnamalai was hoping for a cure. In fact, our wonderful leper hospital was nearby, and my mother sent her there. Unnamalai was completely cured and stayed with us from then on until she retired in the 1980s. She and my mother were an amazing team – my mother was making her hell and Unnamalai didn’t owe her.

My mother turned saving into an art form, and my childhood memories surely contain heaps of unbelievable junk stuck in unbelievable places. The old yellow plastic frisbee became our salad bowl, and other unlikely containers were bowls or bowls that appeared on our table, constantly entertaining our guests. Lucy was indescribably friendly. Almost all who came to the ashram spent some time in our home before going to their own place. My mother felt she was lucky and could be close to everyone with Bhagavan’s grace, so she willingly offered hospitality to anyone who needed her.

My father’s health was almost completely destroyed during his internment as he was more or less starved during the war. My mother studied homeopathy so that she could care for it herself, and she did it for the rest of her life. She took care of its comfort, well-being and every aspect of life. She guided his diet and made him a home where he could feel comfortable. It was a small house, but we loved it. In terms of diet, it seems to me that my father’s regime consisted mainly of removing whatever he liked from the menu – coffee, broad beans, oranges, etc. I stole pieces from him that he liked, but only when my mother was not watching.

My father had a hard time finding work after returning home, and these were troubled times. But with Bhagavan’s help, it was successful. Then Arthur founded the ashram magazine, The Mountain Path, and edited it until his death in 1970. Just before he died, his last word to his wife, my mother Lucia, was “Thank you.”

After the death of her father, Lucia edited the magazine until the arrival of Viswanathan, who took over the work. It was not a small achievement for a Polish woman.

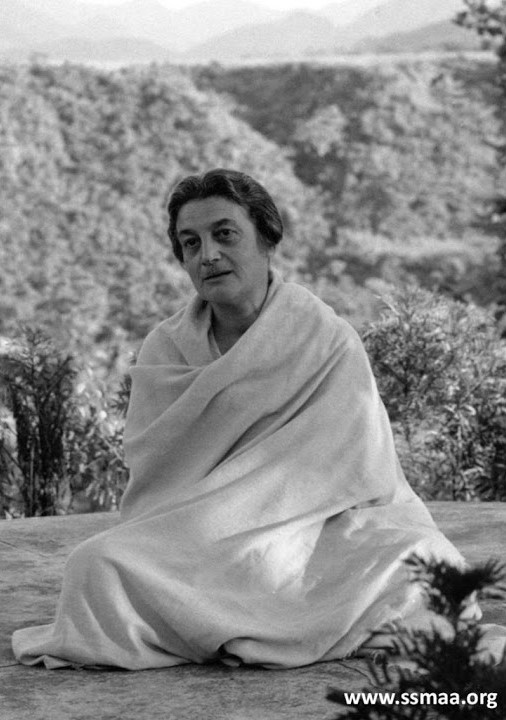

My parents were only 60 when my father died, although he grew old quickly due to the hardships of the war. Lucia’s health began to deteriorate as well, and she spent more time in England since, where she had relatives and the climate was milder. She would probably find a hospitable home in every country in the world, with people who used to live with us in Tiruvannamalai and who continued to correspond with her for the rest of her life. She needed open-heart surgery at the end, but was never completely healthy again. She died in London on December 2, 1987. Before she left us, she had completed the first draft of the book, which included her beliefs and views. Many of them were later published in The Mountain Path.

I was with her until the end, and after cremation, her ashes were placed in my suitcase in preparation for my trip to India. For three days and nights, she harassed me from beyond the grave, saying, “I want to go home, please take me home.” I remember one evening sitting up in bed and telling her, “Look, you’re dead and I’m not. I need sleep, I’m alive and you have to let me sleep. I promise I’ll take you home. Eventually, when she was buried next to my father in Tiruvannamalai, she found peace.

Lucia Osborne was a brave woman who endured all the trials and tribulations of life with total trust in Bhagavan. Even though she was tough and often extremely controversial, she was also exceptionally kind and generous. She had great wisdom, and many loved and respected her. It continues today. I often meet her admirers, people who loved and appreciated her then, and who remember her to this day. indika.pl

Lucia writes – Our stay in Kashmir was nearing its end in September 1941 as Arthur’s six months leave from the Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok was nearly up. We were getting ready to return to Siam without having seen Ramana Maharshi because our friends maintained that it would have been far too hot for the children to go there from April to September. Unexpectedly we received a letter from the British High Commissioner that women and children should not go back as there was the likelihood of the war extending to Siam. Men holding positions of prestige should return. One of our friends, David McIver, had a cottage in Tiruvannamalai and it was arranged for me and the children to stay in it as he himself would be travelling most of the time. I was delighted, probably because of the possibility of making a sculpture of the Maharshi. We all left Kashmir and parted at Lahore.

Arthur on his way back to Bangkok, our friends on their travels and the children and myself to Tiruvannamalai. David had already informed the Ashram about our visit. At the station in Tiruvannamalai we took two horse-carts (jutkas), one for the luggage and the other for us. I did not notice much on the way not even the mountain Arunachala as I was too preoccupied with the children, three live wires, and seeing to it that they did not fall out of the cart and that the street urchins hanging on to the back of the running cart did not get hurt. There was also excitement over Frania who was nearly one year old suddenly starting to speak for the first time and fiercely telling the little boys “Jao, Jao” in Hindi which means “Go, Go” or “Let go.”

Our friend’s commodious cottage was in a spacious garden full of flowers; a riot of colours, red and yellow predominating. The first few days I was very busy getting settled and did not go to the Ashram. Kitty who was five years old then was the first to see him. A sadhu-swami friend of David’s was also living in one of the rooms and he took Kitty to the hall of the Maharshi. She was the first western child to come to the ashram and created quite a stir with her golden locks and appearance. She was used to being stared at and admired and blest. There was a small table or stool before the couch on which the devotees put their offerings but when Kitty stood with her tray of fruit, not quite sure what to do with it, the Maharshi smilingly pointed to the stool and so Kitty, still holding the fruit, sat herself down on it with her back towards the Maharshi! Someone, possibly Bhagavan himself, remarked that Kitty was making an offering of herself. I wondered later how Marpa the Translator, the Guru of the great Milarepa, would have interpreted it.

Before leaving Bangkok for our holiday in India Arthur showed me a booklet, or probably Who am I? Spiritual Instruction received from India with a picture of the Maharshi in it. The picture impressed me greatly as a model, so caught up in sculpture was I at the time. Perhaps this was a sort of vichara (Self-enquiry), in clay to express the essence of the model “Who are you?” Never have I seen a face so alive, so serene and wise, so interesting. Even as a child I used to watch myself and wonder who I was and here was a book showing the way to find out but I was not interested to read it, or simply it did not occur to me to do so. If Arthur was disappointed he never showed it. After arriving in Tiruvannamalai I still had the conceited attitude of judging for myself and finding out just by seeing the Maharshi without ever having gone deeply into his teaching.

On entering the Ashram hall for the first time, from the door I perceived a figure reclining on a couch. Actually I did not see anything much except his extraordinary eyes transparent like water, looking at me. There was no more any question of judging for myself or finding out. Genuine, so transparently genuine, was he that to doubt it would have been like doubting the innocence of a baby; an extraordinary combination of such innocence and great wisdom. I greeted him in Indian fashion with the palms folded in namaskaram and sat down on the floor among others near the couch. I closed my eyes and the thought came to me or it had, I could almost say ‘recalled itself to me,’ “There is only God. All is one.” There was a feeling of great ease mixed with unease. Those eyes could see through me. I sat like that for ten or fifteen minutes. Someone told me that the Maharshi never shifted his eyes from me and that it was very remarkable. But it was not initiation. This happened later.

I started going to the hall mornings and evenings and concentrated on the heart, the spiritual heart on the right side. I did not find meditation difficult but sitting cross legged was another matter. How painful it could be in the beginning. But I persisted.

One early morning I sat down in the hall a few yards from the couch to meditate. Bhagavan was busy with some letters and papers brought from the office. Suddenly it happened. What actually happened is very hard to say. Indescribable bliss of not being weighed down any more, waves of bliss and fear, of lightness, as if my heart was expanding, expanding. In the midst of it I noticed Bhagavan suddenly turning to me with a searching, almost startled look, letters and papers forgotten. Afterwards I tried to describe this experience and it turned out to be a poem which was surprising, as I was not given to writing poetry and find it hard enough to express myself even in prose. The beginning of it I have forgotten. It was something about my confined heart trying to free itself; like a fluttering bird flying out of its cage into the boundless sky, into freedom void.

High, higher so near, Over waves of bliss and fear

High, higher so near, fly heart shrank in fear of death

Was it Life?

Actually the expression ‘high’ does not express it. It was without dimensions or embracing all dimensions, including a bottomless precipice or void. Nothing to hold on to in fearful blissfulness. Words are so limited. I showed it to Bhagavan in the evening. He read it with obvious interest, sat up from his reclining position to read it, then put it under the pillow. A little later I saw him read it again. He did not give it back to me. It felt very much like a near miss.

Soon afterwards the war extended to Siam, the Japanese having invaded the country and all communications from Arthur ceased. Not a single letter for four years. No news at all even through the Red Cross. Prompted by me, Adam, who was about three years old, went up to Bhagavan and asked him: “Bhagavan, please bring back my daddy safely.” Bhagavan nodded, graciously assenting. That was enough. It was astonishing how we did not worry on the whole. Really strange, for someone like me who was given to anxiety and worrying over matters of scarcely any import, watching my anxious thoughts angrily, unable to shut them off. Yes ‘to shut them off’ like a tap, that is what I felt one should be able to do. Worrying never helps, never changes anything, so why harbour and activate such negative feelings?

Often the children would come into the hall, Frania still in the crawling stage on all fours as if prostrating. Once she crawled first to Bhagavan, then to me. He patted her saying to those around, obviously delighted: “You see she did not go first to her mother; Bhagavan comes first with her.” This he said in a most impersonal way. Adam would run jumping for joy and breathing loud like a little colt up and down in the hall between the two rows of seated devotees, men and women apart, occasionally stopping in his tracks to give me a brief hug. Bhagavan looked on with a smile which Kitty described to her father probably in the last letter to reach him from us: “Oh Daddy, I am so happy to be here. When Bhagavan smiles everyone must be happy.”

A most amazing vital period of my life had started.

Catherine (Katya, Kitty) Osborne

From The Mountain Path April 2003 Obituary – ADAM OSBORNE was born in Bangkok on 6th March 1939, but he came to India with his parents at the age of 3. He spent the next 8 years in Tiruvannamalai when he was not in school in Kodaikanal and he played and talked and ran about in and out of the hall where Bhagavan sat. He went to University in England and then took his Ph.D in America where he became a citizen. He married an American and his 3 children were born there.

He was a writer on computer technology and then he invented the first portable computer which was a breakthrough into modern procedure. The system he inaugurated is ongoing and we still don’t know where it will end. He went bankrupt and lost a vast fortune through naiveté in business practices.

He developed Organic Brain Syndrome and came back to spend his last years in India where he died peacefully in his sleep on 18th March 2003, at Kodaikanal.

Adam made a speech about Indians lacking national pride which touched the hearts of almost every Indian who read it. The full text is printed at the back of the journal.

From being a go-getting typical American and epitomising the New World success story, he was forced to retire to a compulsorily quiet life dictated by his illness. His condition deteriorated over a period of ten years to the point where he could neither speak nor move by himself, but throughout this time he behaved with incredible fortitude and dignity. He was unfailingly polite to everyone around him and he never complained. Whatever he needed to learn and however hard it might have been, he became a gentleman who endured everything that was thrown at him with courage and fortitude. His death was, one suspects, a welcome release to him from a life that had become a relentless burden. He is now with Bhagavan.

Blanca Schlamm (Atmananda) (1904-1985), an Austrian concert pianist came to the ashram in 1942 and stayed for six weeks.

Blanca first travelled to India in 1925, to attend the 50th anniversary celebrations of The Theosophical Society, at its headquarters in Adyar, Madras. She returned to India in 1935, and remained there for the rest of her life. In 1942, she went to Tiruvannamalai, to see Ramana Maharshi, hoping that he would be able to give her the peace of mind she had been unable to obtain from JK’s teachings. She stayed for about six weeks.

After an interval of over 12 years, her diary recommences with an entry ‘Ramanashram, 17th May 1942.’ Whilst there, Blanca felt peace and the power of the higher Self; talked to other seekers; visited the mountain Arunachala and had various visions and dreams. Throughout the rest of her diaries Blanca makes reference to Ramana with deep reverence and affection, but her destiny was to become the disciple of another guru, Anandamayi Ma.

Unidentified European Woman in 1943. From Monica Bose’s book The Hill of Fire she writes “It was in 1943 to the best of my recollection, that a young European woman came to visit the Ashram. Since I was spending Christmas in Tiruvannamalai that year, my mother invited some of the Ashramites including this young woman home for a meal. While she was with us I noticed a strange look in her eyes. Nothing in her behaviour, however, gave us any indication of what was to follow. When she got back to her small cottage near the Ashram she found that all her belongings had been stolen. Theft in those parts was not infrequent since the surrounding population was very poor. The shock she got when she found all her things had gone seriously disturbed the balance of her mind, and we heard the next day that she had been found lying naked and unconscious in the ditch that ran along the temple wall. She was taken to the hospital in Vellore for treatment. I saw her again at the Ashram a year or two later and she looked a different person. I think that the Maharshi’s instruction on how to abide in the still centre of oneself, away from the turmoil of thought and emotion, must have helped her, as it did many others.”

In the book Monica goes on further to write about some of the Westerners arriving at the ashram; “Suzanne would become reconciled with her original faith, the Roman Catholic religion. First, though, she had to overcome her prejudice against the Church, which she had long believed to be intolerant and arrogant in its attitude towards other religions. The lack of understanding and the righteous superiority generally shown by Christian visitors to the Ashram had done little to mitigate that opinion. Most Christians came there predisposed to negate everything that the Maharshi told them in the course of their talks with him, which they usually kept very brief, as if afraid of being led astray by him into pagan ways of thinking. A friend of mine from Madras, after spending just a short time in the hall came out in a state of some agitation. He admitted to me that he had felt the Maharshi was about to hypnotize him, as that was what he had been told to expect by some members of his Christian community in Madras. Suzanne had only contempt for such an attitude. But then, her own attitude would be transformed after she met, on her return to Tiruvannamalai in 1952, two notable Christian religious, a missionary priest, Father Jules Monchanin, and a Benedictine monk, Dom Henri Le Saux also known as Swami Abhishiktananda. In 1950 they had founded together a Christian contemplative ashram, Shantivanam, on the banks of the Kaveri River near the small town of Kullitalai some 240 kilometres south of Tiruvannamalai.”

William Samuel (1924 – 1996) sat with Ramana Maharshi in 1944. While a 21 year old captain in the US Army and a veteran of three years fighting with the Chinese Nationalist army against the Japanese in China, he took a period of R&R at the ashram where he stayed for two weeks in April of 1944. He writes in one of his books The Awareness of Self-Discovery about his time with Ramana Maharshi. “Some years ago, I was honoured to be the first American student of a renowned teacher in India. For fourteen days a group of us sat at the feet of this “Master,” during which time he spoke not one word – not so much as a grunt – until the final day when he bade us farewell and assured us we had learned much. And to my surprise, I had… It took months before the seeds of those silent days began to sprout one by one, revealing that there are indeed many things for which the uptight, recondite babble of books and teachers is more hindrance than a help.”

William Samuel (1924-1996) was a renown spiritual master of metaphysics and higher Truth. He was known as the teacher’s teacher. He passed along his knowledge with brilliance and humble humor as a writer and speaker for over 40 years. William Samuel devoted his life to the search for Truth. His quest to study at the fountainheads of the world’s ideas took him twice around the globe, into its remotest places. His journey included time in China with Mr. Shieh the venerated Taoist Monk and, in 1944, a visit with Ramana Maharshi in India. Mr. Samuel’s ability to instruct in a clear, simple and effective way has lead many to discover the fabled “peace beyond understanding.” wiliamsamuel.com

The Awareness Of Self-Discovery (1970) by William Samuel, is a book is for those who want Illumination itself, not a description of it – and for those who want to know how to live it. William Samuel did not embrace the idea of being called a teacher, saying “I’ve been telling my own story – how it happened and what it has allowed me to understand–for over 30 years. That is not the same as being a teacher.” He was a prolific writer of truth, science, religion, and spiritual awakening and authored many books.

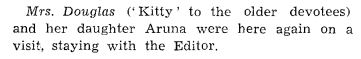

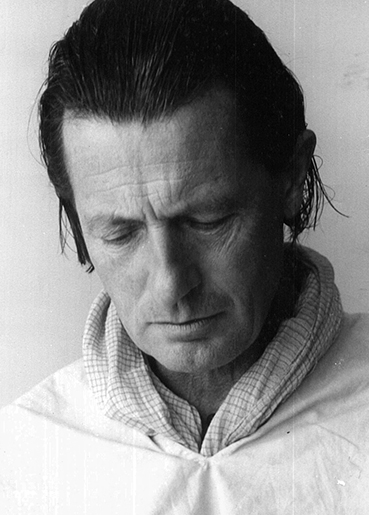

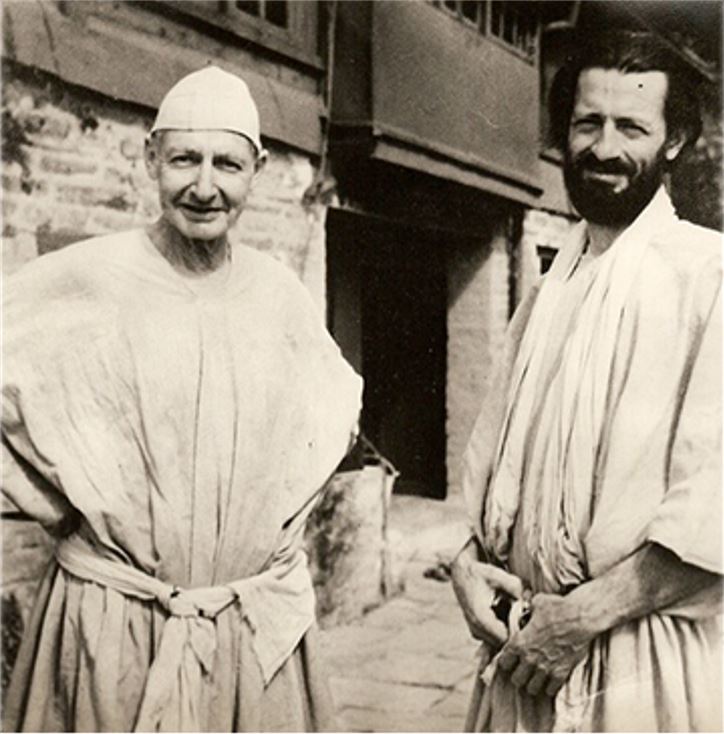

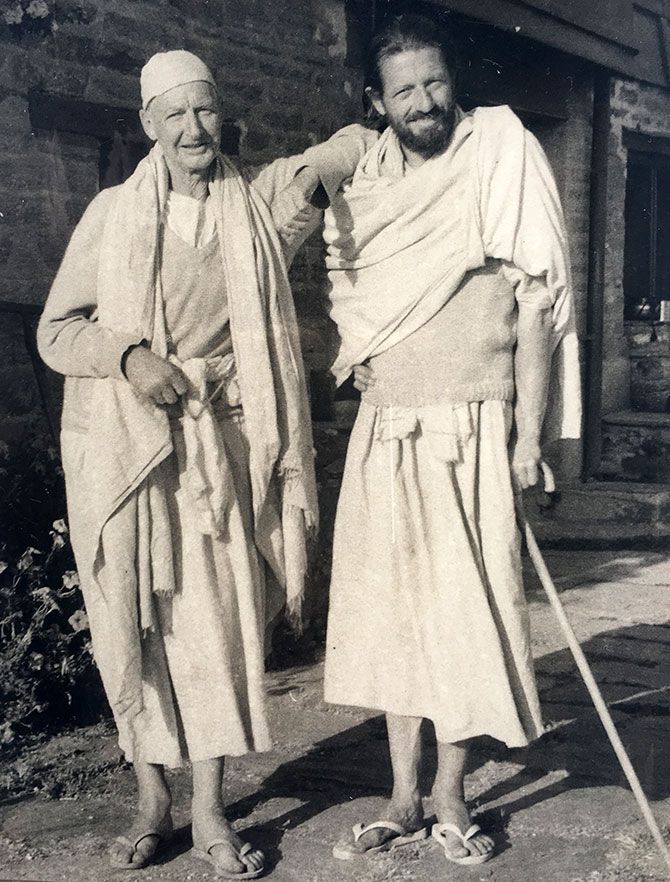

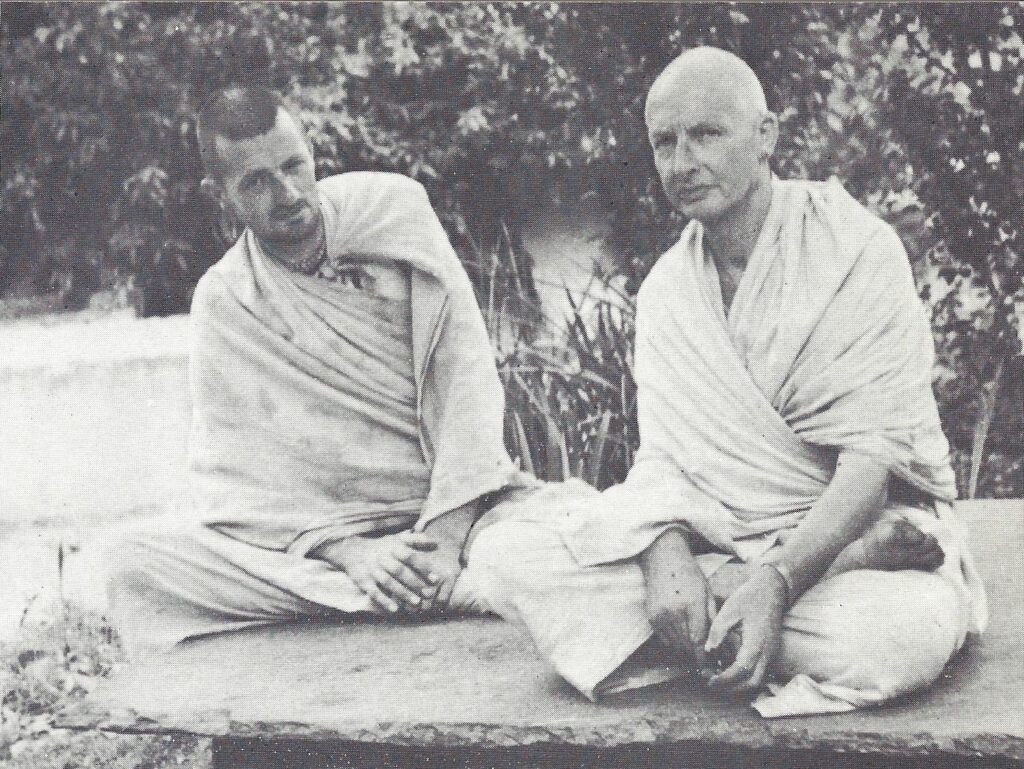

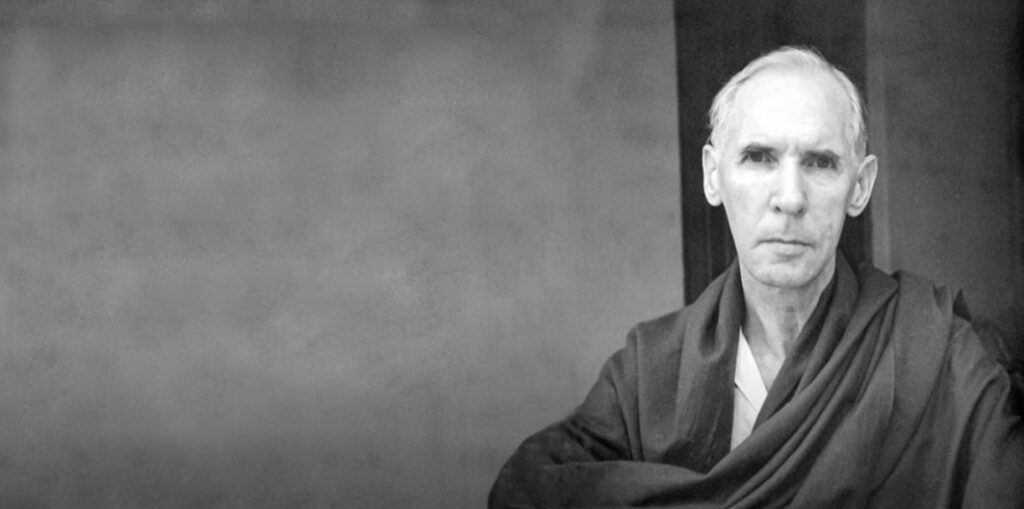

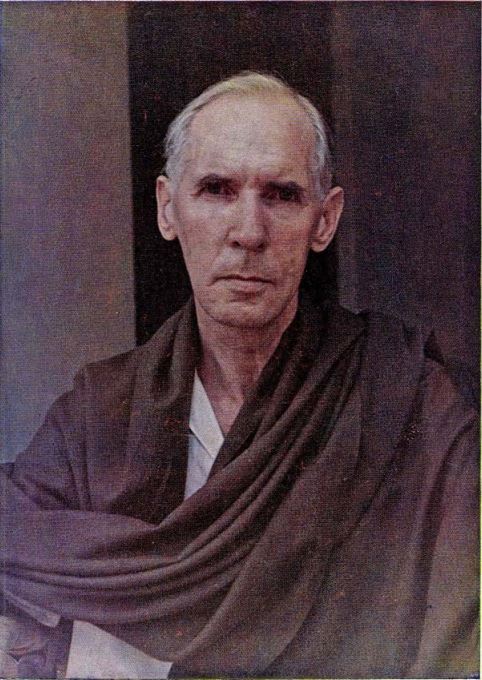

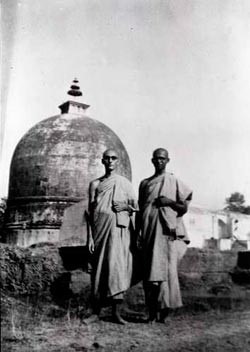

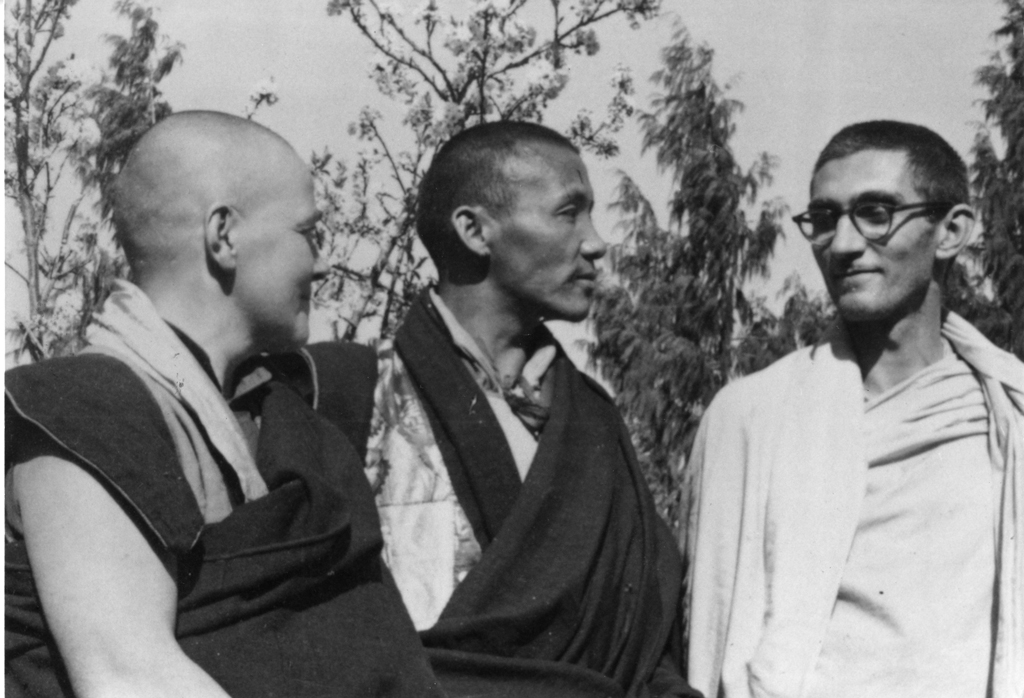

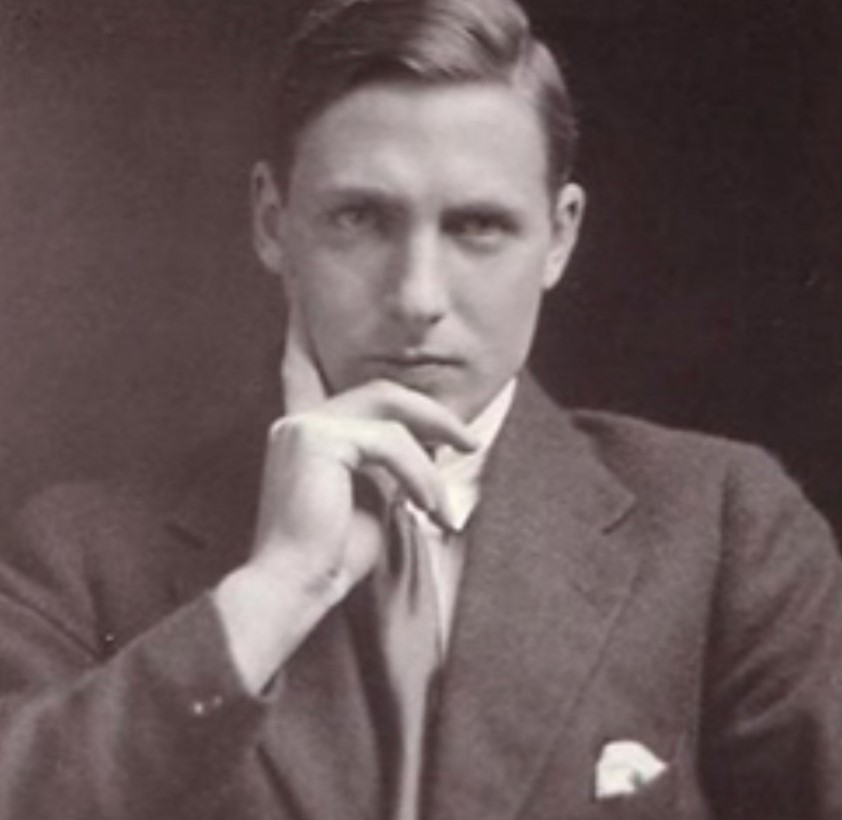

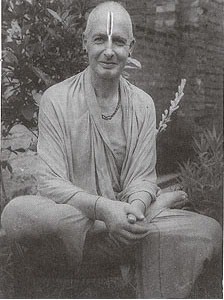

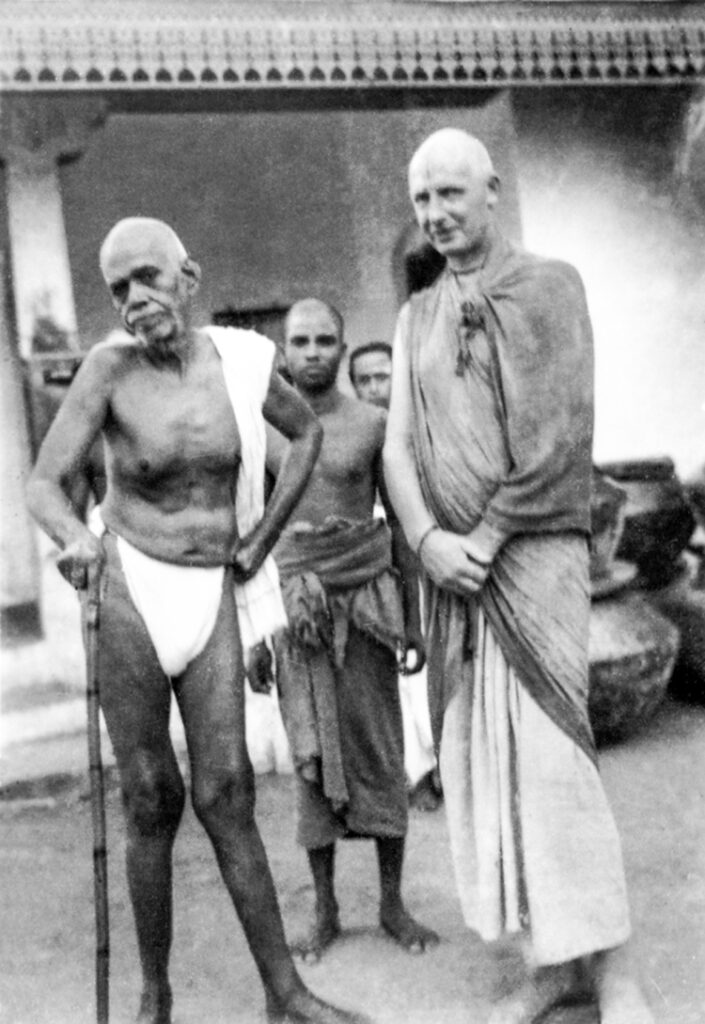

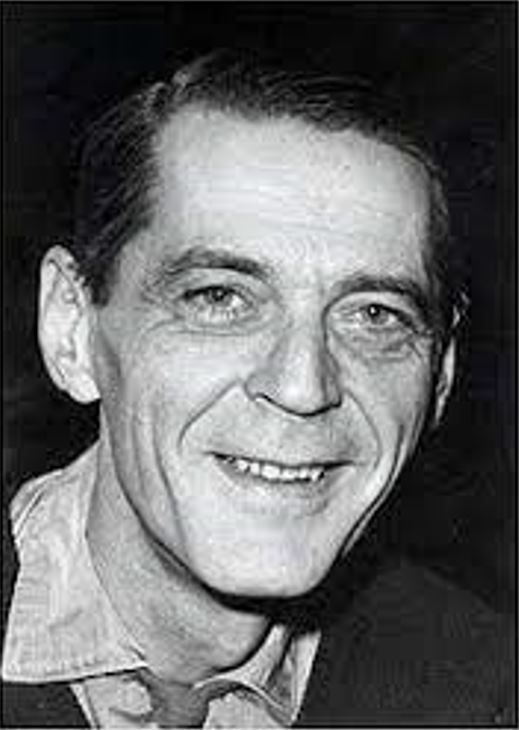

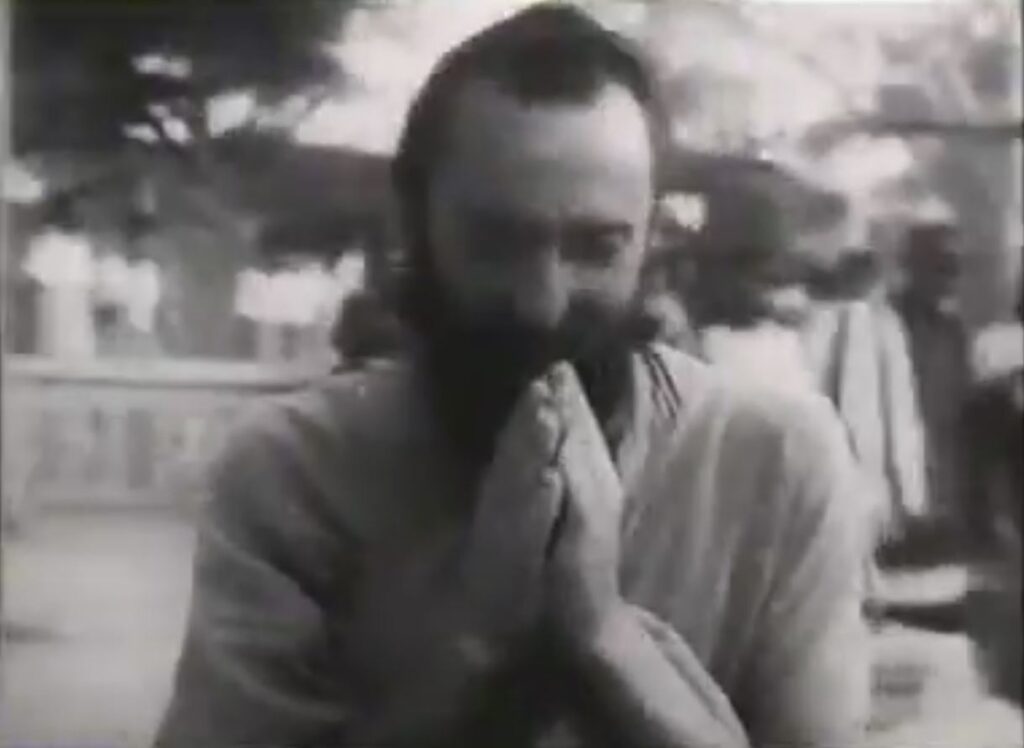

Alexander Phipps (Madhava Ashish) visited in 1944, and his guru Ronald Nixon (Krishna Prem) visited in 1948. Madhava Ashish (1920 – 1997) was a Hindu mystic with many European followers, who began his life as a conventional member of the old officer class.

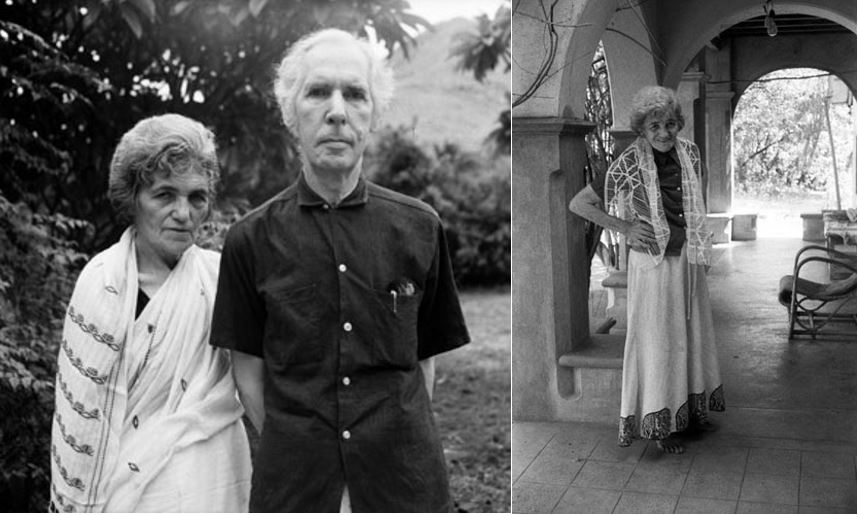

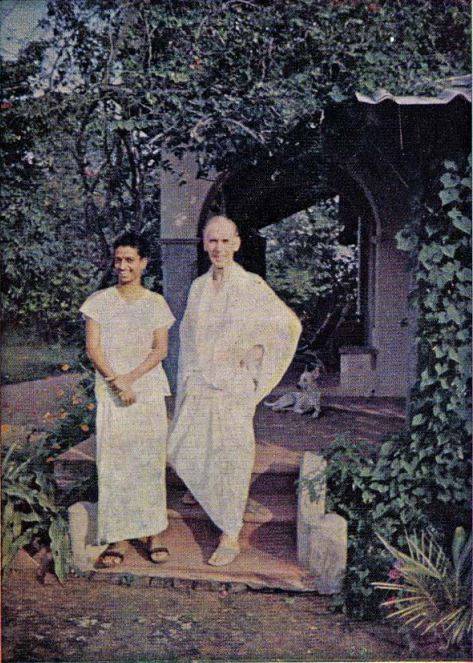

This photo is from Himalayan Memoirs by Navnit Parekh – Sri Madhav-Ashish and Swami Sri Krishna-Prem at Mirtola-Ashram.

Australian travel writer Frank Clune visited in early 1944.

Francis Patrick Clune, OBE, (27 November 1893 – 11 March 1971) was a best-selling Australian author, travel writer and popular historian.

From his 1946 book Song of India he writes –

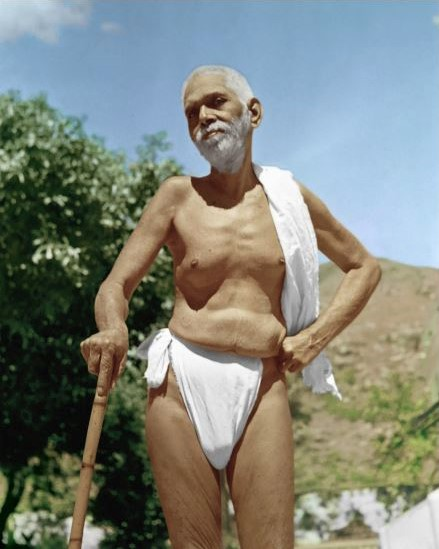

My next pilgrimage was to the Ashram of Shri Maharshi, the ‘Saint of Tiruvannamalai,’ about 70 miles from Pondicherry. I stayed a day and a night in this Ashram, and had a talk with the saint, who is not a silent one, like the Yogi of Pondicherry. In fact, Shri Maharshi is a likeable old chap, very human and approachable.

Born in the south of India about 70 years ago, he began having ‘‘visions’’ in his ‘teens, and, obeying a ‘‘voice,’’ he went to Tiruvannamalai, where he’s been ever since. Not highly educated in ‘‘book-learning,’’ he has attracted disciples and established an Ashram solely by the extreme spirituality of his personality, and by the simplicity of his teachings, which are taken down in the Tamil language by his disciples, translated, and printed as ‘‘gospels.’’ Great is his fame, and he is venerated by the multitude. People come from all over India just to see him. He gives his blessing free to everybody who asks for it. In some queer way, that is all his own, he “radiates’’ peace and spiritual joy.

Shri Aurobindo is a ‘‘ learned ’’ saint, while Shri Maharshi is a ‘‘simple’’ saint – but both have arrived at the same goal of self-purification by the spiritual discipline of Yoga, the Indian system of mind-control.

The aim is “ecstasy,’’ to be attained through meditation. The Christian saints, down the ages, have also achieved ecstasy, or “union with God,’’ by prayer and meditation, and by monastic spiritual discipline, becoming revered for their purity of soul, which works miracles. This may be the same thing as “Yoga,’’ but under a different name. India is the land where holy men still strive to be saints, of the non-Christian variety. They are revered as truth-seekers and truth-finders. In or bustling, money-crazed modern civilization, we are inclined to jeer at saints, both Christian and non-Christian – but it may be that the saints, seeking and finding peace, inner peace, can well afford to smile benignantly at those who mock them.

India’s message to the Western world – and even to modern Christianity – is that life without religion is incomplete. Whatever form the religion may take, whatever name of God may be invoked, the devotee who seeks the Truth sincerely will find at least something more than he who never seeks at all.

Before leaving the Ashram, I attempted to interview the saint – but he turned the tables and interviewed me for half an hour, quizzing me about my adventures in many lands. What interested him most, I think, was my mention of the Stone Age aborigines of Central Australia, and of the giant stone named “Oolera’’ – Ayer’s Rock – the biggest gibber in the world, an aboriginal place of pilgrimage.

I got only one good question in, asking him the meaning of the tiger-skin on which he sat. ‘‘It is a symbol of my fierceness to protect my religion,’’ was his smiling reply.

“But what is your religion?’’ I innocently asked.

“Seeking the truth,’’ was his prompt reply.

So ended my pilgrimage to the Saint of Tiruvannamalai. I think it is not so much his actual teaching as his calm and serene atmosphere which attracts disciples. He appears, in some indefinable way, to have entirely purged his soul of evil, and to emanate goodness in a kind of aura. To our westernised minds, the whole rigmarole has its funny side, when reduced to descriptive words – but actually the old boy isn’t funny at all. He’s immensely dignified and convincing as a kind personality. Some Christian bishops also have this quality – but I doubt whether they could radiate it, sitting clothed only in a loin-cloth, on a tiger-skin!

Download: Song of India by Frank Clune

https://archive.org/details/dli.csl.6610

https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.06414/page/3/mode/2up

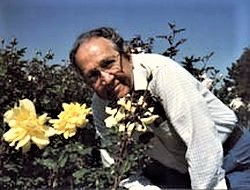

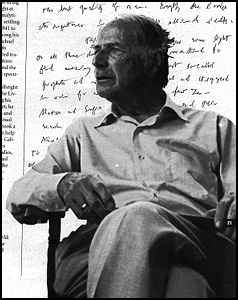

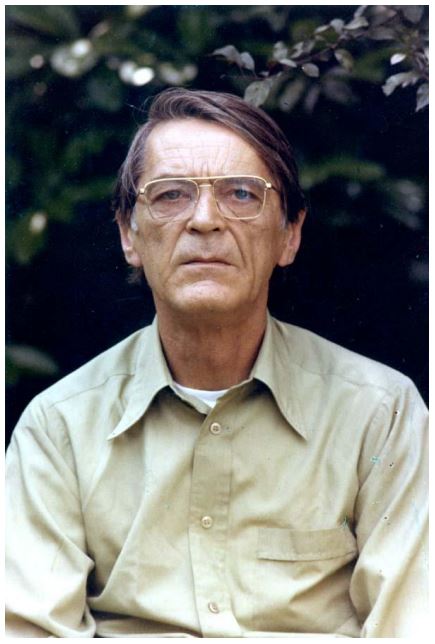

Writer Arthur Osborne (1906 – 1970) was initially was a follower of the French metaphysician René Guénon. One of the members the René Guénon group, David MacIver, sent the Osborne family a photograph of Ramana Maharshi and two of Bhagavan’s books, cautioning them that Ramana Maharshi was not a guru as he did not give initiations or accept anyone as a disciple. But Arthur and Lucia Osborne were captivated by the picture wanted to go to India and meet Ramana Maharshi. During a summer holiday Kashmir in 1942, they were met by David MacIver who also owned a cottage opposite Ramanasramam. After a few weeks, Osborne had to return to Bangkok, Lucia and the three children went with McIver to Tiruvannamalai.

Parting at the Lahore railway station, Lucia and the children went on to Bombay and then south, and Arthur went to Calcutta and then on to Thailand. From My Life And Quest, Arthur writes that his daughter Catherine was the first to see Bhagavan. She stepped into the hall where he used to sit, a small, beautiful child with curly gold hair, bearing a tray of fruit in her hands, the customary offering. Bhagavan pointed to the low table beside his couch where such offerings were placed, and she, misunderstanding, sat down on it herself, holding the tray in her lap. There was a burst of laughter. “She has given herself as an offering to Bhagavan,” someone said. A day or two later my wife entered the hall and sat down. Immediately Bhagavan turned his luminous eyes on her in a gaze so concentrated that there was a vibration she could actually hear. She returned the gaze, losing all sense of time, the mind stilled, feeling like a bird caught by a snake, yet glad to be caught. An older devotee who watched told her that this was the silent initiation and that it had lasted about fifteen minutes. Usually it was quite short, a minute or two.

Osborne returned to Bangkok he was taken as a POW and held for three and a half years by the Japenese. Osborne’s only solace was Bhagavan’s picture and the two books. When the Japanese came to arrest him from the university campus, some urge prompted him to take these three things. While in the prison camp, he created and tended to a very nice garden. His personality, and his talks there, drew many people to him. One among them was Louis Hurst, who came to Bhagavan after the Second World War.

Osborne arrived in Sri Ramanasramam in 1945, following his internment to be reunited with his family. He describes his first meeting with Ramana Maharshi in My Life And Quest, “I entered the ashram hall on the morning of my arrival, before Bhagavan had returned from his daily walk on the hill. I was a little awed to find how small it was and how close to him I should be sitting; I had expected something grander and less intimate. And then he entered and, to my surprise, there was no great impression. Certainly far less than his photograph had made. Just a white-haired, very gracious man, walking a little stiffly from rheumatism and with a slight stoop. As soon as he had eased himself on to the couch he smiled at me and then turned to those around and to my young son and said: ‘So Adam’s prayer has been answered; his Daddy has come back safely.’ I felt his kindness but no more. I appreciated that it was for my sake that he had spoken English, since Adam knew Tamil.”

Their bungalow was built by his wife Lucia and four workmen, without a plan and without an architect.

Apart from a three year period in Madras and another time in Calcutta from 1952 to 1958 for work, he made Tiruvannamalai his home, spending the rest of his life there writing and raising his children (who were the first Western children at Ramanasramam).

Osborne authored many books about Ramana Maharshi, he also founded and published the ashram journal The Mountain Path which still enjoys a global circulation. He died in 1970, his body much weakened by the effect of his years in the internment camp.

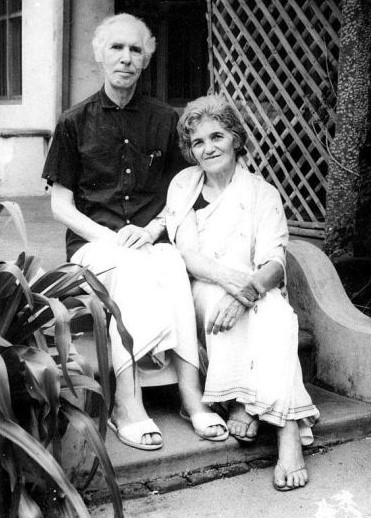

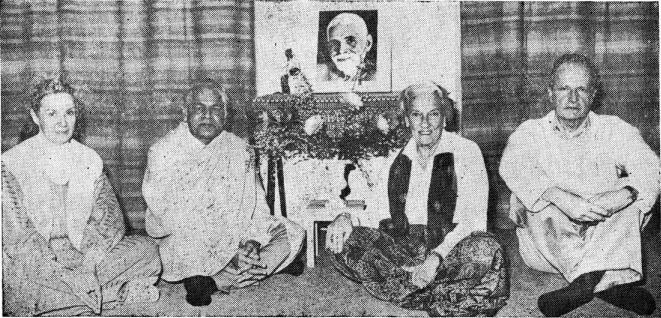

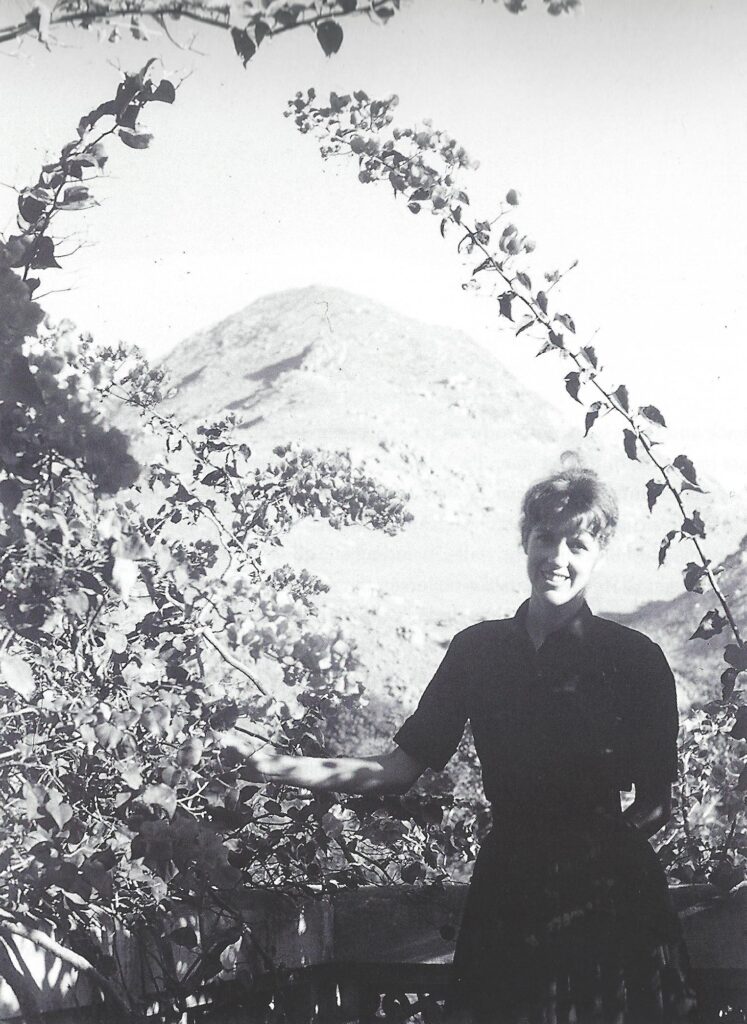

The photo of Lucia Osborne at the bungalow near Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai on the 29th of January 1981, was taken from the 2004 book New Lives, 54 Interviews with Westerners on their search for spiritual fulfilment in India (newlives.freeola.net) Compiled, edited and mainly photographed by Malcolm Tillis. Lucia spoke fluent Tamil and practised Homeopathy.

Nagar, after their return from England in 1969, Photo: The Mountain Path October 1969.

Mr. & Mrs. OSBORNE After a year’s absence abroad, Mr. & Mrs. Osborne have returned back to Sri Ramanasramam looking very much better. They had been to Europe for a change of climate and rest following a period of Mr. Osborne’s illness and heavy work . They almost lived in retirement, in England and in Spain and are sorry not to have been able to meet all friends interested in Sri Bhagavan’s teachings and devoted to Him . They feel confirmed in their impression about the unrest and spiritual hunger prevalent, particularly among young people in the world of disintegrating values, without anchorage at certainty, and their seeking for guidance which they need. If and when Mr. Osborne repeats his visit abroad, he hopes to be of all help he can in the service of Sri Bhagavan. We are all very glad that they are back at the abode of Sri Bhagavan.

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Face_to_Face_with_Sri_Ramana_Maharshi.pdf

An excerpt form Chapter 15 of the biography Ramana Maharshi And The Path Of Self-Knowledge written by Arthur Osborne;

My three children, the only European children at Tiruvannamalai, were conspicuous among the devotees. One evening in December 1946, Sri Bhagavan initiated the two elder of them into meditation, and if their efforts to describe it fail, so do those of older people. Kitty, who was ten, wrote: “When I was sitting in the hall this evening Bhagavan smiled at me and I shut my eyes and began to meditate. As soon as I shut my eyes I felt very happy and felt that Bhagavan was very, very near to me and very real and that he was in me. It wasn’t like being happy and excited about anything. I don’t know what to say, simply very happy and that Bhagavan is so lovely.”

And Adam, who was seven, wrote, “When I was sitting in the hall I didn’t feel happy so I began to pray and I felt very happy, but not like having a new toy, just loving Bhagavan and everyone.”

Not that children sat often or long hours in the hall. When they felt like it they sat; more often they played about.

When Frania, the youngest child, was seven the other two were talking about their friends and she, having no real friends yet but not wanting to be left out, said that Dr. Syed was the best friend she had in the world. Sri Bhagavan was told.

“Ah?” he replied, with perfunctory interest.

And her mother said, ‘What about Bhagavan?’

“Ah?” This time he turned his head and showed real interest.

“Frania said, ‘Bhagavan is not in the world’.”

“Ah!” He sat upright with an expression of delight, placing his forefinger against the side of his nose in a manner he had when showing surprise. He translated the story into Tamil and repeated it delightedly to others who entered the hall.

Later Dr. Syed asked the child where Bhagavan was if not in the world, and she replied, “He is everywhere.”

Still he continued in Quranic vein, “How can we say that he is not a man in the world like us when we see him sitting on the couch and eating and drinking and walking about?”

And the child replied, “Let’s talk about something else.”

The Mountain Path October 1970 is almost entirely taken up with the life story of Arthur Osborne.

Download:

https://realization.org/down/mountain-path/7-4.1970-Oct.pdf

An article by Ravi S. Iyer How Arthur Osborne was directed by Ramana Maharshi in dream to write the book, The Incredible Sai Baba (on Shirdi Sai)

https://ravisiyer.blogspot.com/2019/12/how-arthur-osborne-got-directed-by.html

Osborne’s fellow POW, Dutchman, Louis Hartz would visit after the Second World War.

From The Mountain Path, April 1964, How I Met The Maharshi by Louis Hartz.

I met Arthur Osborne in an internment camp in Bangkok during the Second World War. At first I had little contact with him because he was very reserved. After some time, however, I approached him. I had a craving to understand and asked him point blank what is Truth. What sticks in my memory is how, sitting beside his bed in the common dormitory, he said. “I will tell you one truth – Infinity minus X is a contradiction in terms because by the exclusion of X the first term ceases to be infinite. You grant that?” Yes, I granted that.

“WELL, then,” he said, “think of God as Infinity and yourself as X and try to work it out.” When I asked for more explanation he just said: “Think this over and come tomorrow at this time and tell me what you make of it.”

I returned to my place in the dormitory, which was only some eight or ten steps distant, and suddenly it flashed upon me that he was right, that you cannot take anything away from the Infinite, and that I was not apart from it, only I had not known.

The thought made me so happy that I could hardly wait to speak to him the next day, but I did not like to disturb him earlier.

From that time onward he started to instruct me and after a few weeks he showed me a photograph of the Maharshi. There was an urgency in his voice as he spoke of him and he handled the photograph with reverence. I began to understand that there was only one ‘I’ and that it was in me and was everywhere.

The Maharshi grew so much in my heart that I felt him nearer to me than my parents or my wife. He lived more vividly in me than any person I had known. After some time we received permission to write a Red Cross letter to our families and I used mine to write to the Maharshi and ask him for guidance.

Then the war ended and I left the camp. The desire to enjoy life sprang up in me again.

I was strongly drawn to the spiritual path but even more strongly, for the time being, to a worldly life. I wanted to make money, to have power and fine clothes, to be important. In camp I had eliminated day-dreaming as far as possible. When I went to bed at night I slept straight away. But now my nights were often filled with planning and scheming.

A few years later when I was in Europe and due to return to Siam on business, I wrote to Osborne, who was living at Tiruvannamalai, to suggest that I should break my journey in India and stay there for a few days. He at once wrote back arranging to meet me and conduct me there and invited me to stay at his house.

In Madras we hired a car and drove to Tiruvannamalai. It was an old car and I felt that I was being slowly roasted in the midday heat. When I let my eyes rest on the sunbaked scenery or the country folk sheltering under the wayside trees I saw only the face of the Maharshi looming up before me. Nothing else registered.

I was terribly scared that the Maharshi would look in my eyes and see into me. I cursed myself for a fool for coming to this desolate place, with its heat and discomfort. I don’t know what prevented me from turning back; perhaps I was afraid to show Osborne what a coward I was. The nearer we approached the Ashram the more I shrank from meeting the Maharshi.

It was nearly dusk when we arrived and he had already retired, but Osborne went in to see him and asked whether he would see me for a few moments. I entered the hall and saw an elderly man reclining on a couch, who gave the impression of great reserve and certain shyness. It was not the severe Master or the Guru with the burning eyes that I had expected. Osborne explained who I was, and his replies were monosyllabic and sometimes in Tamiḷ. With a slow movement of the head he turned to me and held my eyes for a moment. His eyes were like empty, bottomless pools and at the same time they worked like magic mirrors, because suddenly I felt at peace, as though I had come home after a long journey.

I can’t recall where I slept that night, but I do remember that before going to bed I sat and talked with a number of people, Indians and foreigners, at Osborne’s place. One of them was a diplomat from some European country, stationed in China. He talked about seeing spirits and even conversing with them, and it struck me as funny that anyone should be interested in such things at a place like this.

Sitting in the hall the next day I saw that the Maharshi’s smile was tender and gracious. I not only lost my fears but felt at ease. I had no questions to ask. Before coming I had prepared a number of questions that had been worrying me to ask the Maharshi, but now I couldn’t remember them. My doubts had simply evaporated. Questions seemed unimportant.

I felt that there was nothing strange about the Maharshi. He was just a man who was himself, whereas all of us were growing away from ourselves. He was natural; it was we who were not. We call him a saint or sage, but I felt that to be like him is the inheritance of everybody; only we throw it away.

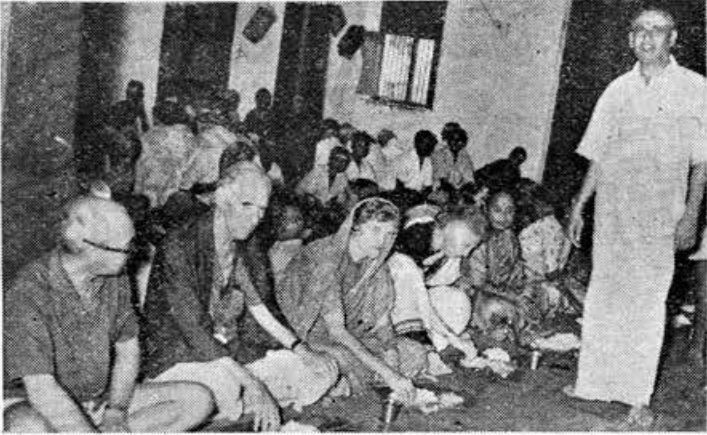

There were a lot of people in the hall – Indians and foreigners, learned professors and simple country people. I reminded the Maharshi about the Red Cross letter I had sent him and he replied that he wanted me to come and I had come. There was something childlike about him: he was free and natural and could laugh with the spontaneity that only a child shows.

A discussion started in the hall and they appealed to the Maharshi to say who was right. Someone spoke about unity and I objected that the word implied two to be united and that a better word was Oneness; and the Maharshi confirmed this. He said that there is only One, and that One is indivisible. I felt that he meant that the divisions are all unreal, just as we say rain, ice, water, coffee, washing water, but it is all water.

A group of devotees started singing and I asked the Maharshi what he felt about it. He laughed and replied that it pleased them to sing and made them feel peaceful.

Next morning again I sat in the hall. There was a yogi with matted hair. The diplomat was there, sitting in concentrated thought. I wondered whether I should imitate him, but I did not feel like meditating. Suddenly the Maharshi looked at me with great intensity. His eyes took possession of me. I don’t know how long it lasted, but I felt at ease and happy.

Afterwards, a disciple who had been with him for twenty years told me that this was the silent initiation. I felt that it probably was, but I wanted to make sure, so in the hall that afternoon I said: “Bhagavan, I want your initiation….”

And he replied: “You have it already.[1]”

Knowing myself and feeling anxious about what would happen when I left his presence, I asked for some sort of reassurance from him, and he replied very firmly and decisively: “Even if you let go of Bhagavan, Bhagavan will never let go of you.”

There was some whispering and exchange of glances when people heard that. The diplomat whispered to a Muslim professor who was sitting beside him and then the latter asked the Maharshi whether this guarantee applied only to me or to him also. The Maharshi did not look very pleased but replied briefly: “To all.”

Nevertheless, I felt that there was something intensely personal in it, that it had been a confirmation of the initiation and a direct, personal guarantee of protection. Certain it is that, whatever else may have happened, there has been no day since then when his face or his words have not influenced me.

— Mountain Path, April 1964

Footnote:

[1] This is the only occasion on which I have ever known the Maharshi give an express verbal confirmation of having given initiation to anyone. It will be noted that the request was phrased in such a way that the confirmation could be given without any statement implying duality. [The Mountain Path Editor]

From My Life and Quest by Arthur Osborne;

Louis Hartz was one who approached me himself. A very conspicuous young man from Holland who, for some reason or other, had not been evacuated with the rest of the Dutch; short, with black hair and eager eyes, he was obviously seeking.

Several times he engaged an associate of mine in long discussions but went away unconvinced. Then I saw him walking up and down the camp with an elderly gentleman who had at one time been the head of a school or college and overheard a snatch of their talk as they passed:

“When I was younger I read the Bible, but of course I don’t believe it now.”

“Well — er — Mr.Hartz, what exactly in the Bible do you not believe?”

“All of it.”

In view of such a brash reply, it can be imagined that I was not disposed to explain to him at any great length, much less to enter into an argument, when he approached me a day or two later and announced that he wanted to know the Truth. “I will tell you one truth,” I said. “Infinity minus x is a contradiction in terms, because by the exclusion of x the first term ceases to be infinite.”

Yes, he saw that.

“Very well, then,” I told him, “think of Infinity as God and x as yourself. Now go and think it over and come tomorrow and tell me what you make of it.” That was all; no more explanation.

When he came back next day he told me that there had been no need to think it over. Before even he got back to his place in the dormitory it had flashed on his heart that it was true.

He had been ripe for understanding and therefore a single explanation had been enough. Moreover, it had been the right kind of explanation that I was led to give him, because, like my wife, he had the intuitive type of mind which cannot read a whole chapter about what can be said in a sentence.

He could never read Guenon, but he read and re-read the Tao Te Ching. However, brilliant initial understanding is no guarantee of a smooth or rapid quest. Since Realization is quite different from mental understanding, every preoccupation with the ego is an obstacle to progress on it. The process must continue until the whole nature is transmuted and all egoism dissolved.

The internees found various occupations during the daytime; in the evening many of them used to sit around on the lawn in small groups, and ours formed one group among the others. A certain power flowed through me at that time.

Sometimes two of the group would discuss some point and decide to ask me about it in the evening, and when evening came I would spontaneously explain it without the question being raised. One person who joined us was of a psychic disposition, and the first time he sat in our evening group he saw a vortex of blue light encircling it and rising to a spiral in the centre. In general I had a feeling of how to respond to the needs of the various people, what to say and do.

This illustrates the dangers of a false guru. There is nothing personal in such powers. I had never consciously practised telepathy and I myself never saw any blue lights; even if I had it would have meant nothing; and yet on the basis of such happenings a man can build up a reputation for himself and start posing as a guru, and if he attributes the power to himself it will be both to his detriment and to that of the people he is supposed to be guiding.

Fortunately I was not drawn into any such aberration. Indeed, before the camp broke up I had ceased to exert any influence or to guide the others at all. There was a psychic crisis in camp when one went mad and most of those who had joined me took fright and drew back. That was what was visible outwardly, but inner events are more fundamental, and in myself I felt at this time a cessation of the power of guidance. I no longer felt that I knew what to do and say; I no longer felt any influence over the others; nor did they any longer feel it. This did not seem to me a privation or a cause for regret, simply a change of course, because the interest in guiding others

evaporated together with the power to do so. I vaguely felt it to be a transfer from the spiritual influence of the order into which I had been initiated to that of Bhagavan. More and more I felt his presence and he seemed to dominate and to bestow grace.

Although I had only seen him in photographs, his face was more vivid to me, more easily visualized, than any I had ever known. I was content simply to feel his pervading graciousness without occupying my mind at all with what I had been told about his not being a guru.

Bhagavan, as I was later to discover, did not encourage people to play the guru, even to the limited extent to which I had been doing so. He would not absolutely forbid it, for that would be doctrinaire. If asked he might say: “If it is a man’s destiny to be a guru he will be.” And he knew that some of his devotees acted so. But on the whole he discouraged it. Even apart from the direct and obvious danger of flattering a man’s ego and perhaps inducing him to let himself be regarded as a realized man when he is not, it means a turning of the energy outwards when the aspirant still needs to turn it inwards. If it does not actually put a stop to his further progress, it at least makes it more difficult.

And what happened afterwards? Of all those I had known in camp only Hartz was drawn to Bhagavan after the war. For the first year or two he concentrated on building up a business and making money. Then he broke a business trip from Europe to Thailand to spend a few days at Tiruvannamalai. It was the hot season when I was in the hills with my family. The children were going to a convent school in the hills and we used to spend several months there in the summer, so as to be able to take them out of the boarding house and have them at home with us. I went to Colombo to meet Hartz and we spent the night at the house of K. Ramachandra, a friend who always welcomed devotees of Bhagavan. Next day we flew to Madras and stayed with Dr. T.N. Krishnaswami, another devotee. The railway journey from there to Tiruvannamalai is roundabout and takes a whole day and night, and the excellent bus service which now plies had not yet been started, so Hartz hired a car for the trip. He was not averse to showing the advantages of being wealthy.

Bhagavan was very gracious to him. Indeed, a photograph of Bhagavan taken by him on this trip is evidence enough of the love and encouragement with which Bhagavan regarded him. He received the initiation by look, but, although told by the devotees that this was Bhagavan’s mode of initiation, he wanted to make quite sure and therefore said: “I want Bhagavan’s initiation.” Bhagavan replies: “You have it already.” This is the only occasion of which I know when he explicitly confirmed having given initiation.

In another way also Hartz desired assurance: he perhaps feared that when he got back into life of the world with all its distractions his steadfastness might weaken. He asked Bhagavan for some guarantee and was given the tremendous assurance: “Even if you let go of Bhagavan, Bhagavan will never let go of you.”

Once Bhagavan has taken up a person, his destiny becomes more purposeful, is speeded up, so to say. From a worldly point of view this may be for good or ill; prosperity may be needed for one man’s development, adversity for another. Evidently Hartz was of the latter type, because from this time his business got into difficulties and within a few years it had evaporated completely. He had planned to come back and even to build a house at Tiruvannamalai, but he was not able to. How many such cases have I seen, where the first visit was made easy but a planned return was frustrated year after year! He went through many vicissitudes and for a period of years I did not hear from him at all; but Bhagavan did not let go of him.

Day by Day with Bhagavan From the Diary of A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR.

https://selfdefinition.org/ramana/Ramana-Maharshi-Day-by-Day-with-Bhagavan.pdf

23/12/1945 Afternoon; Mons. Georges Le Bot, Private Secretary to the Governor of Pondicherry, and Chief of Cabinet of the French Government there, came to Bhagavan. He could not easily squat down on the floor and so Bhagavan asked us to give him a seat. We placed for him a chair opposite to Bhagavan. He had brought with him his request written in French. After expressing his greetings to Bhagavan through some interpreters who came with him and who spoke Tamil, he produced his French writing. Our Balaram Reddi tried to interpret the same to Bhagavan.

But he found it rather difficult, as the French was rather high-flown. So we sent for Mr. Osborne (whose wife and three children have been living for nearly five years here and who himself returned from Siam about a month back) and he came and explained the gist as follows: “I know little. I am even less. But I know what I am speaking about. I am not asking for words, explanations or arguments, but for active help by Maharshi’s spiritual influence. I did some sadhana and attained to a stage where the ego was near being annihilated. I wanted the ego to be annihilated. But at the same time I wanted to be there to see it being killed. This looked like having contradictory desires. I pray Maharshi may do something by his influence, in which I fully believe, to enable me to reach the final stage and kill the ego. I do not want mere arguments or explanations addressed to the mind, but real help. Will Maharshi please do this for me?”

He had also written out another question: “I have been having for my motto ‘Liberate yourself’. Is that all right or would Maharshi suggest any other motto or ideal for me?”

Bhagavan kept silent for a few minutes, all the while however steadily looking at the visitor. After a few minutes the visitor said, “I feel that I am not now in a state in which I can readily receive any influence which Maharshi may be pleased to send. After some time, I shall come again when I am in that state of exaltation in which I may be able to assimilate his influence or spiritual help.” He added, “May I have a little conversation with this interpreter (Mr. Osborne) and come here some other time?” Bhagavan said, “Yes, you can certainly go and have some talk.” They both went out. The Sarvadhikari gave the visitor some fruits and coffee and he took leave expressing his desire to come here some other time. After the visitor left the hall, Bhagavan said, “He seems to have read about all this and to have done some sadhana. He is certainly no novice.” Someone suggested that the books in French, in our library, on Bhagavan’s teachings might be shown to the visitor. They were accordingly taken out and shown to him while he was still with the Sarvadhikari, having coffee. He looked at them and said he had read them all.

In the evening, after parayana, Mr. Osborne said that before Mons. Georges Le Bot left, he said the following: “I had the experience described by me, twice, first by my own efforts, and the second time under the silent influence of a French philosopher now dead, who held my wrist and brought me to the same stage without any effort on my part. Both times I kept approaching the breaking point in waves but shrank back. It was because of the second experience that I decided that Maharshi could again bring me to that point.”

Day by Day with Bhagavan From the Diary of A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR.

https://selfdefinition.org/ramana/Ramana-Maharshi-Day-by-Day-with-Bhagavan.pdf

02/04/1946 In the afternoon, an European walked into the hall, sat in a corner and walked away after a few minutes. Bhagavan turned to me and asked me if I didn’t know him. I told Bhagavan I had seen him here before, but I had forgotten his name. He is a friend of Mr. McIver. Bhagavan said, “His name is Evelyn. His wife — don’t you know he married that Parsi girl who used to come and stay with Mrs. Taleyarkhan — has written to Viswanathan to look after her husband, saying he had come out of the hospital and that he is better now.”

Day by Day with Bhagavan From the Diary of A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR.

https://selfdefinition.org/ramana/Ramana-Maharshi-Day-by-Day-with-Bhagavan.pdf

31/5/1946 Mr Phillips, an Englishman who used to be a missionary and is now a teacher and who has been about 20 years in Hyderabad, came this morning. He said: “I lost my son in the war. What is the way for his salvation?”

Bhagavan was silent for a while and then replied. “Your worry is due to thinking. Anxiety is a creation of the mind. Your real nature is peace. Peace has not got to be achieved; it is our nature. To find consolation, you may reflect: ‘God gave, God has taken away; He knows best’. But the true remedy is to enquire into your true nature. It is because you feel that your son does not exist that you feel grief. If you knew that he existed you would not feel grief. That means that the source of the grief is mental and not an actual reality. There is a story given in some books how two boys went on a pilgrimage and after some days news came back that one of them was dead. However, the wrong one was reported dead, and the result was that the mother who had lost her son went about as cheerful as ever, while the one who had still got her son was weeping and lamenting. So it is not any object or condition that causes grief but only our thought about it. Your son came from the Self and was absorbed back into the Self. Before he was born, where was he apart from the Self? He is our Self in reality. In deep sleep the thought of ‘I’ or ‘child’ or ‘death’ does not occur to you, and you are the same person who existed in sleep. If you enquire in this way and find out your real nature, you will know your son’s real nature also. He always exists. It is only you who think he is lost. You create a son in your mind, and think that he is lost, but in the Self he always exists.”

K.M. Jivrajani: What is the nature of life after physical death?

Bhagavan: Find out about your present life. Why do you worry about life after death? If you realize the present you will know everything.

Day by Day with Bhagavan From the Diary of A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR.

https://selfdefinition.org/ramana/Ramana-Maharshi-Day-by-Day-with-Bhagavan.pdf

13/9/1946 Today, one Mrs. Barwell (whose husband, it is said, is a barrister now staying at Almora), accompanied by the principal of the Women’s Christian College at Madras, visited the Asramam. The former comes introduced by Miss Merston and has already written to the Asramam for accommodation. The Asramam has not been able to find accommodation for her. But today, Mr. McIver has promised to find accommodation for her in his compound and so she is planning to go and come back here with her things in a week’s time. Her friend also goes back with her and intends to spend the forthcoming dasara holidays here with some of her students. This lady (the principal) seems to have already met some well-known disciples of Bhagavan, such as Grant Duff.

Mrs Barwell (whose husband was a barrister in Almora), accompanied by Miss Eleanor Harriet Rivett (1883 – 1972), principal of the Women’s Christian College in Madras, visited in September 1946.

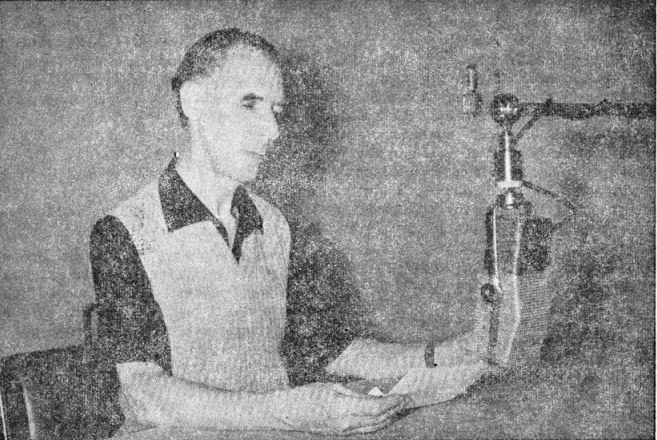

From the Wireless Weekly March 25 1938 News Talks – March, April – page 4