Series: Westerners in India.

The following is an expanded and more compressive article that is sourced from Ashrams of India Volume 2.

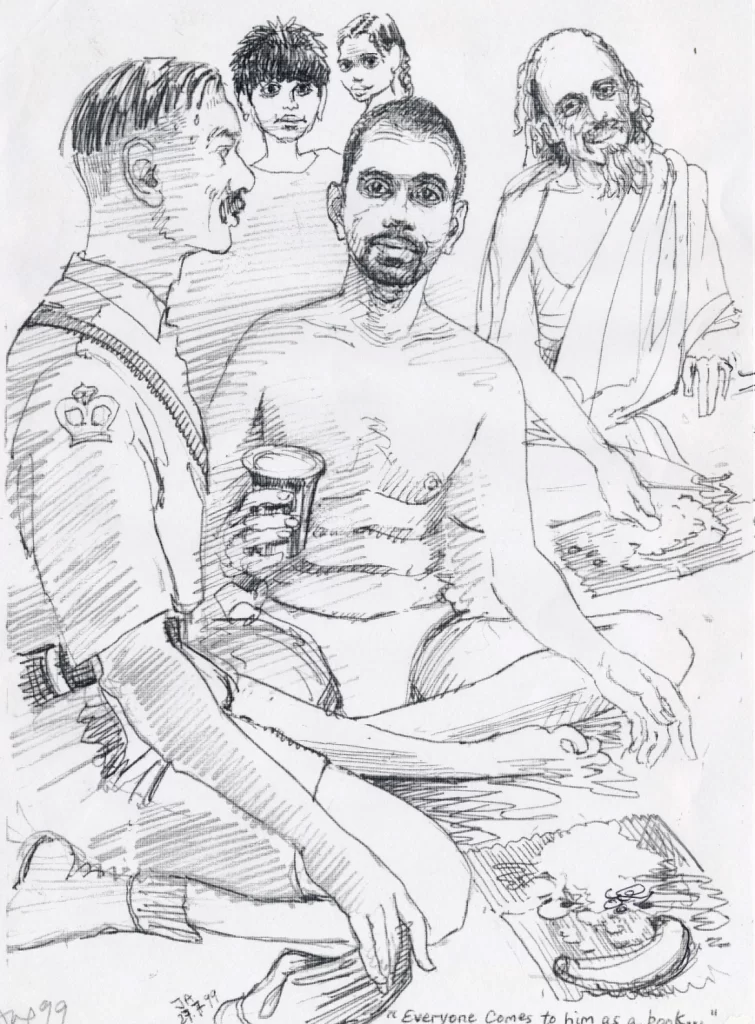

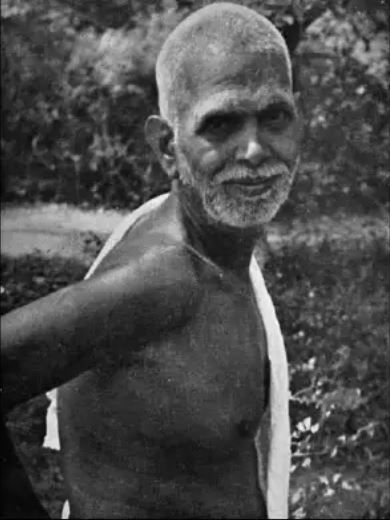

In 1911, Frank Humphreys, a policeman stationed in India, became the first Westerner to discover Sri Ramana. He wrote articles about him which were first published in The International Psychic Gazette in 1913.

Sri Ramana only became relatively well known in and out of India after the publication of two books in 1934 and 1935 by Paul Brunton, who had first visited him in January 1931 along with Bhikshu Prajnananda (former military officer Frederick Fletcher known later as Swami Prajnananda).

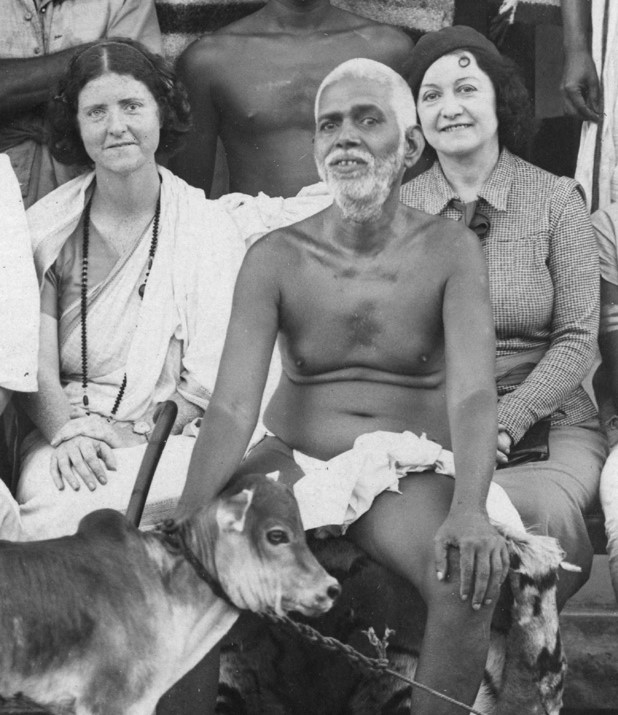

Some of the other foreign visitors that followed included Maud Alice Piggot who in January 1935 is thought to be the first English lady to visit Sri Ramana,

American social psychologist, Professor Pryns Hopkins (Prynce Hopkins) visited Sri Ramana after reading about him in Paul Brunton’s A Search in Secret India,

Grant Duff (Douglas Ainslie 1865 – 1948) was a Scottish poet, translator, critic and diplomat born in Paris, France, visited in 1935,

American anthropologist and writer Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz in 1935,

American Chemist Dr Bernhard Bey in 1935,

Paramahansa Yogananda (accompanied by his secretaries Richard Wright and Ettie Bletsch) in November 1935,

Maurice Frydman, a Polish-Jewish devotee who was a research engineer working in Bangalore was a frequent visitor from 1935,

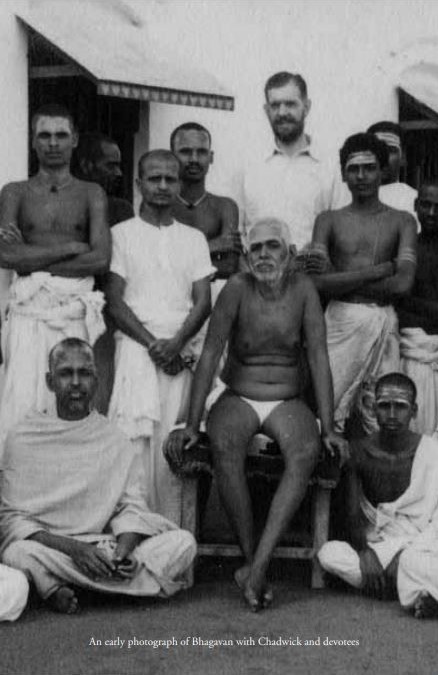

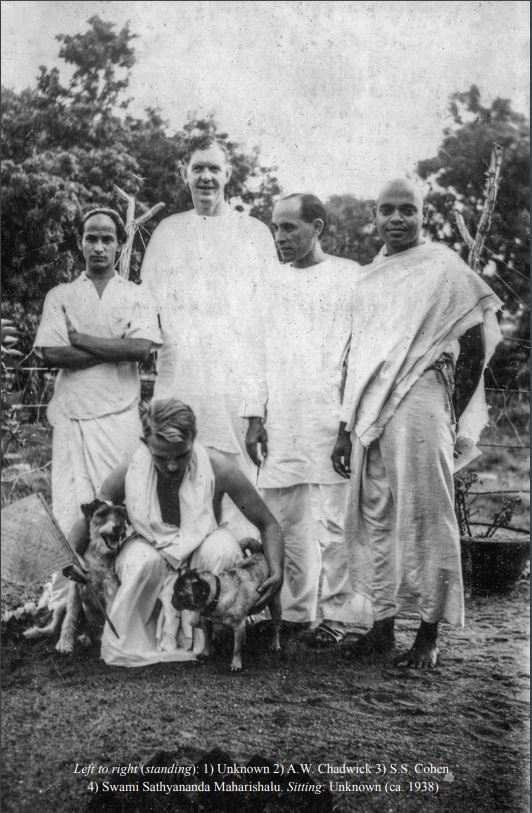

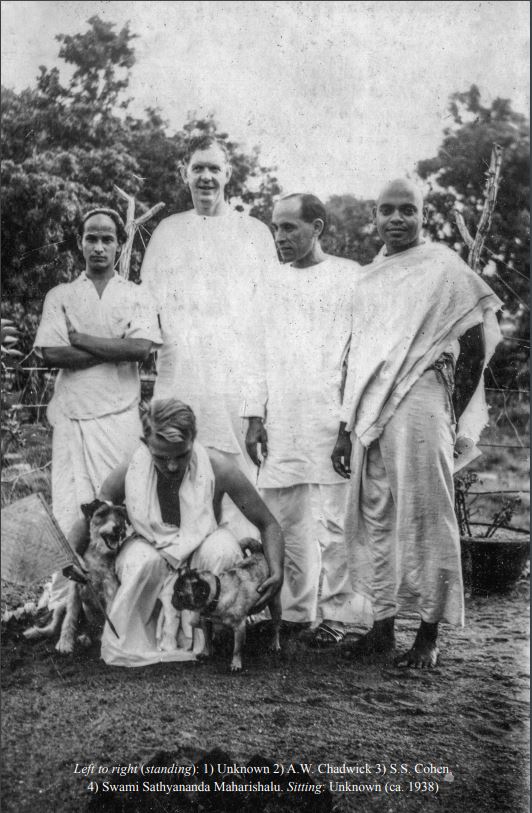

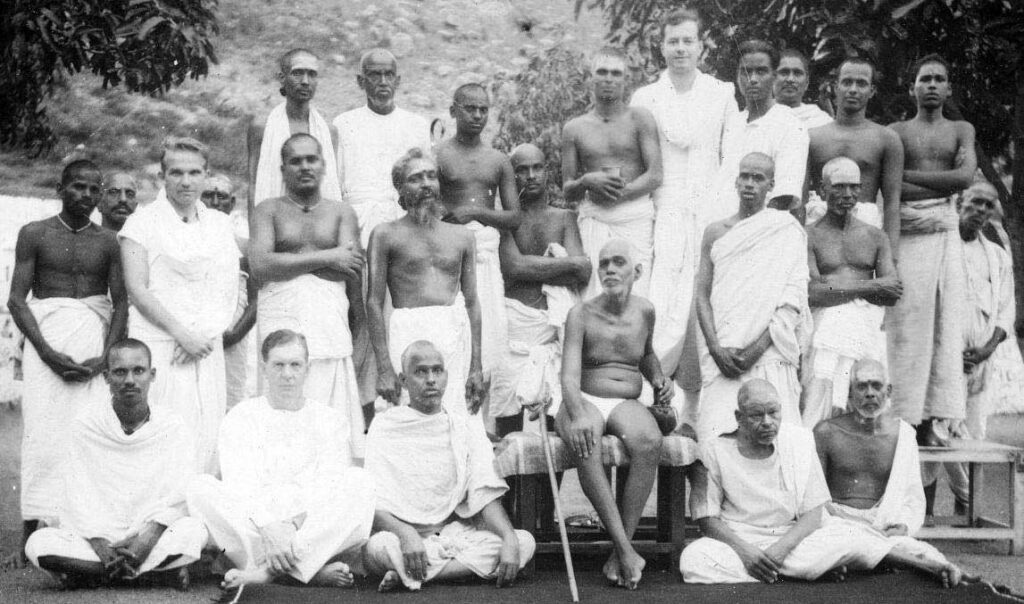

Major A.W. Chadwick in November 1935,

Hans-Hasso Ludolf Martin von Veltheim-Ostrau in December 1935,

English Poet Lewis Thompson in approximately 1935 and stayed for 7 years,

Polish writer Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) lived in India from 1935 until her death in 1971 visited often,

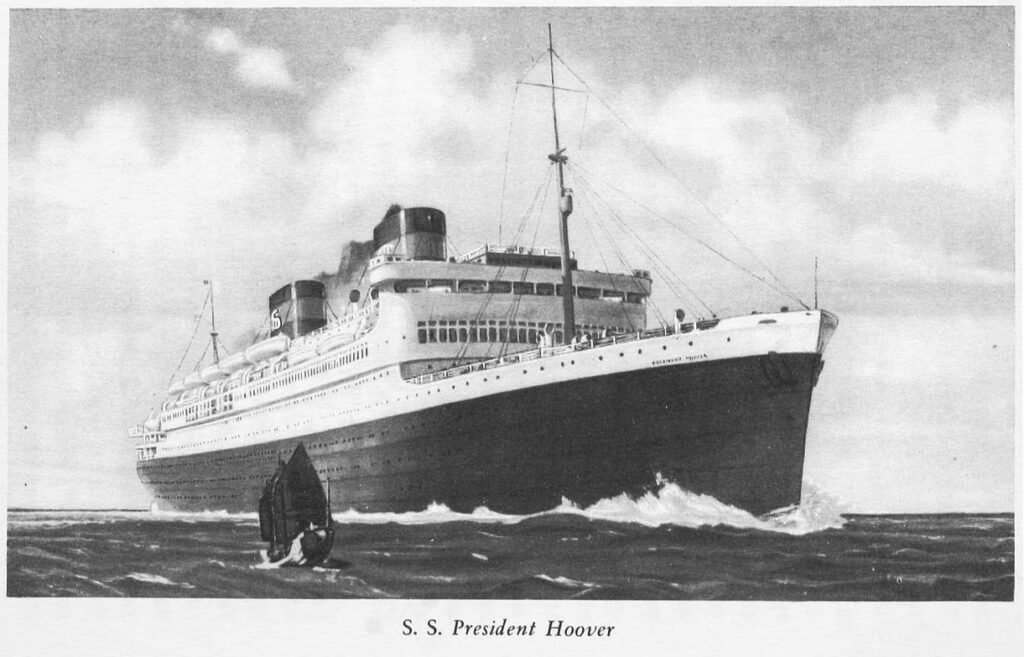

American spiritual writer, author of the spiritual book series Life and Teaching of the Masters of the Far East, Baird T. Spalding (1872 – 1953) with a party of tourists that included the American couple Mr and Mrs Taylor in 1935 or 36,

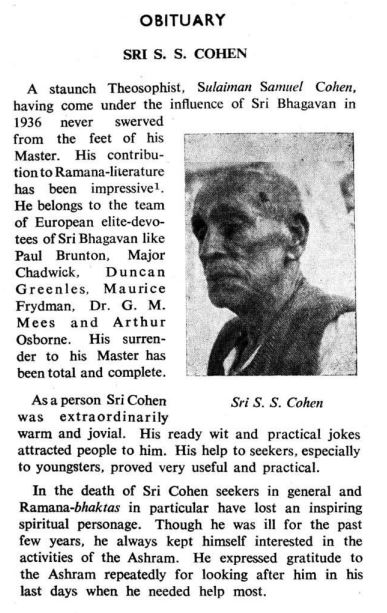

S.S. Cohen, an Iraqi Jew, who made Ramanasramam his home in 1936,

American Dr Henry Hand in 1936,

American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger visited in January 1936,

There were some French ladies and gentlemen and American as visitors to the Asramam in January 1936,

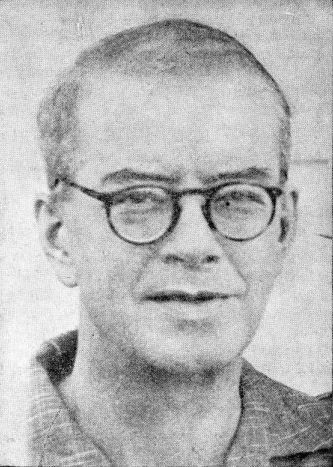

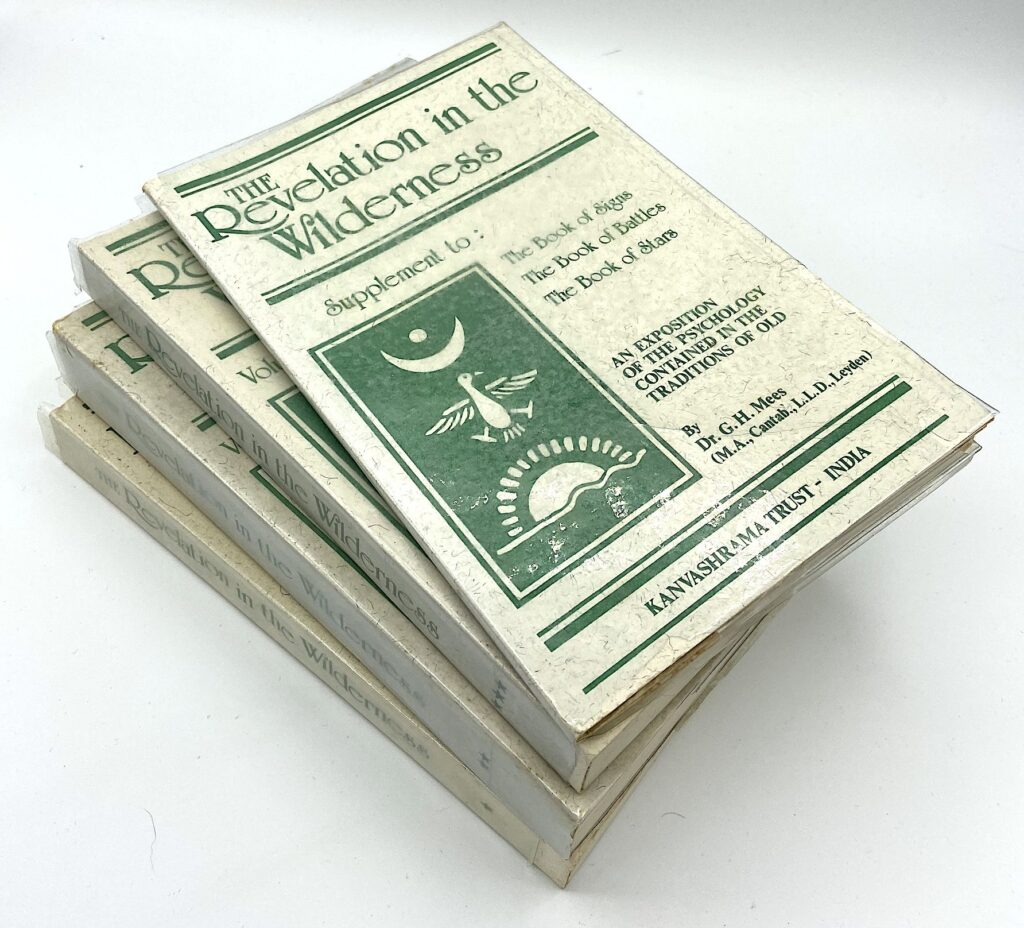

33 year old Dutchman Sadhu Ekarasa (Dr G.H. Mees) came in 1936, (he mentored Hildegard Elsberg, a German Jew who lived in India for 10 years from 1937, teaching at a convent school in Kodaikanal – it is not known when she first arrived in the ashram but is thought to be 1937/38),

Olivier Lacombe (L’Attache Culturel, Consulat General de France, Calcutta) was a French doctor of philosophy who came for darshan in May 1936,

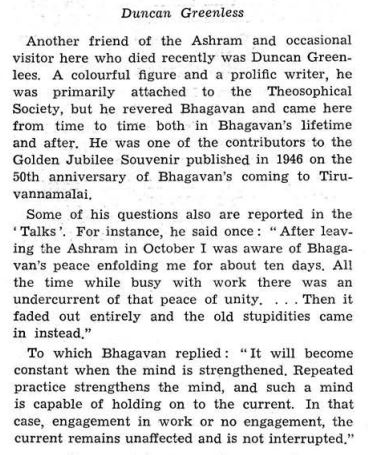

British scholar and Theosophist Duncan Greenlees, came in October 1936 for a few days,

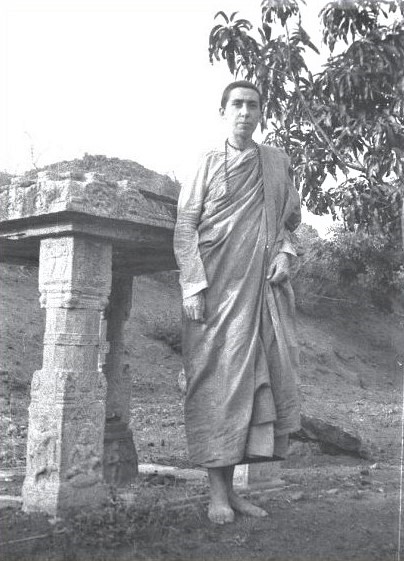

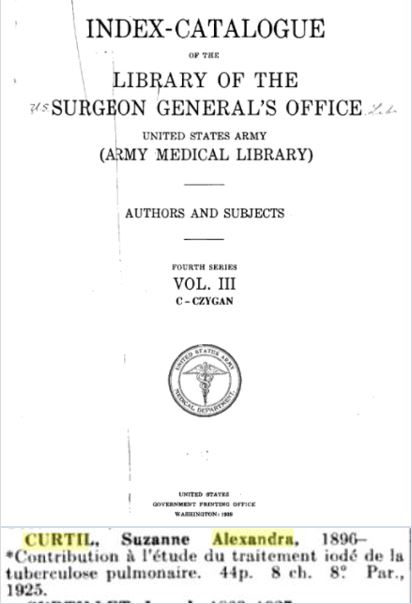

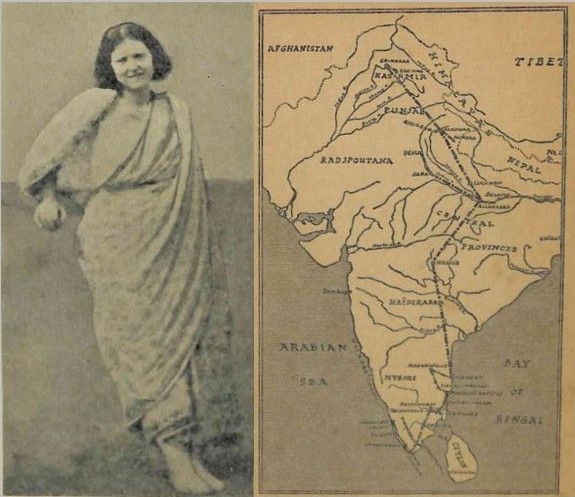

French Dr Suzanne Alexandra Curtil Sen (Sujata Sen) in December 1936,

Pascaline Mallet visits in December 1936, a French writer and seeker whose 1938 book Turn Eastwards details her nine-month pilgrimage in India from December 1936 to September 1937,

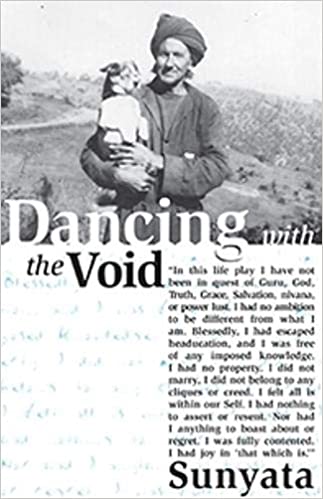

Alfred Julius Emmanual Sorensen (Sunyata) was a Danish devotee made the first of four trips to Ramana in 1936,

American Mrs Roorna Jennings of the International Peace League, January 1937,

Professor Banning Richardson arrived in May 1937 and stayed for three days,

Swiss author Lizelle Reymond and future husband Jean Herbert in 1937,

David MacIver in 1938,

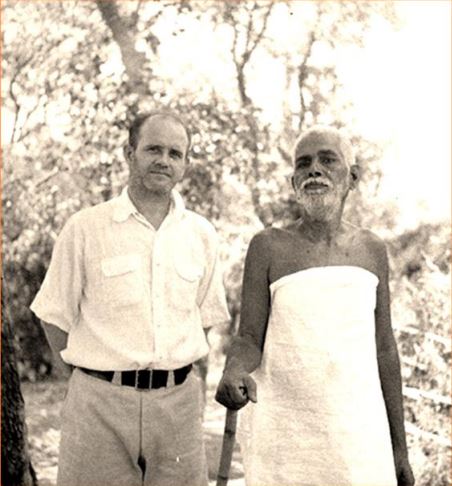

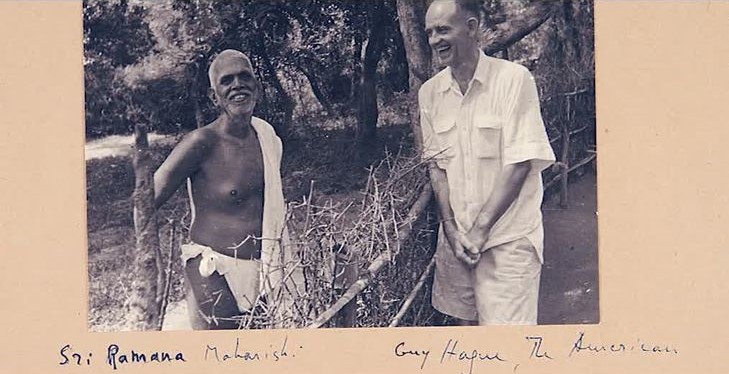

American engineer Guy Hague arrived in Sri Ramanasramam in 1938 after travelling the world, he stayed 2½ years,

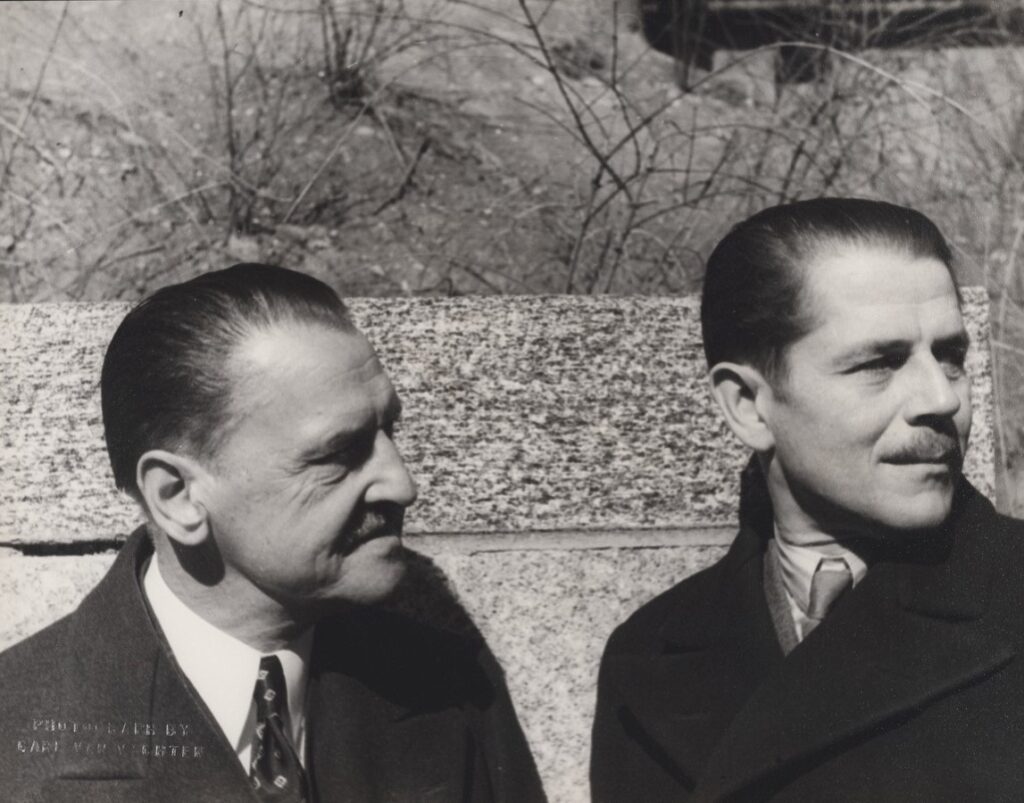

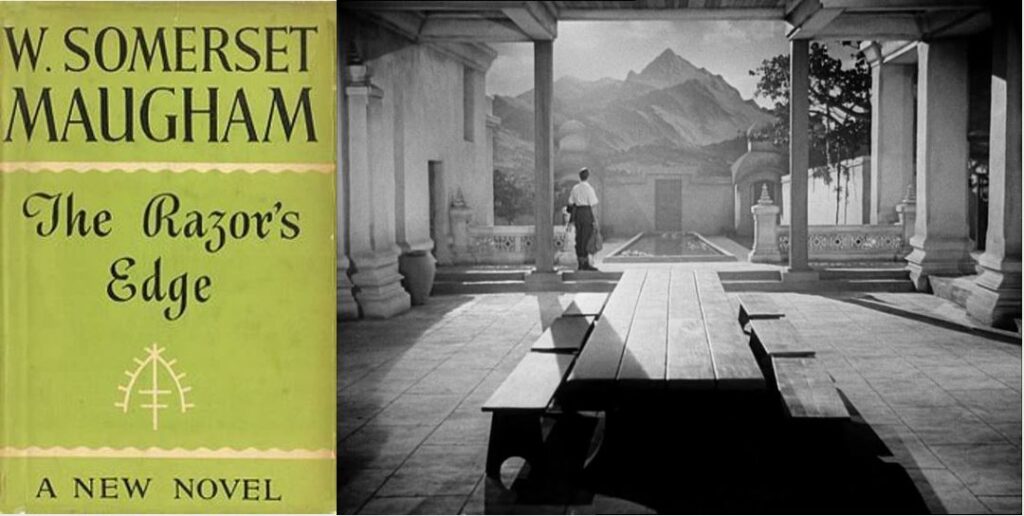

Christina Austin brought Somerset Maugham (and his companion Gerald Haxton ?) to the ashram in January 1938 for a few hours (his 1944 novel The Razor’s Edge models its spiritual guru after Sri Ramana),

Three ladies on a short visit in Feburary 1938, Mrs Hearst from New Zealand, Mrs Craig and Mrs Allison from London,

A young English woman, identified as Miss J, arrived in May 1938, dressed in a Muslim sari, she had evidently been in North India and met Dr. G. H. Mees,

An American gentleman, Mr J. M. Lorey in June 1938,

Cuban-American writer of the 1920s and 30s Mercedes de Acosta stayed for three days in 1938,

renowned American painter Eliot C. Clark visited in 1938,

from Morocco, Bernard Duval in 1938 for about 15 days,

Two ladies, one Swiss and the other French, visited Maharshi in December 1938,

English woman Miss Ward-Jackson 1938/39,

Eleanor Pauline Noye arrived in 1939 and stayed for 10 months,

Ethel Merston visited in 1939,

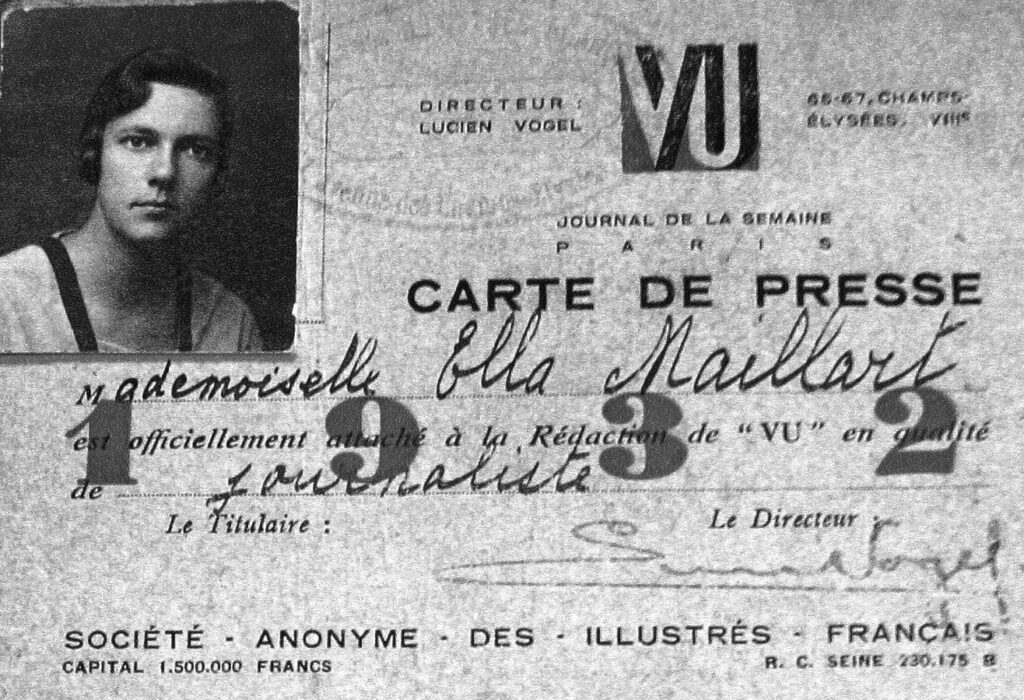

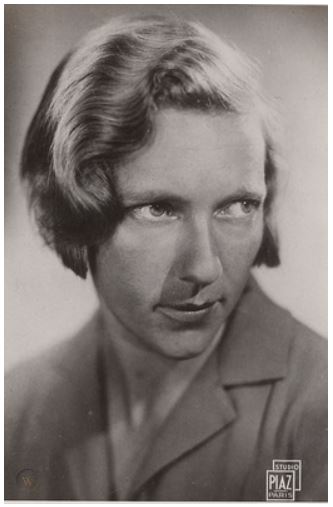

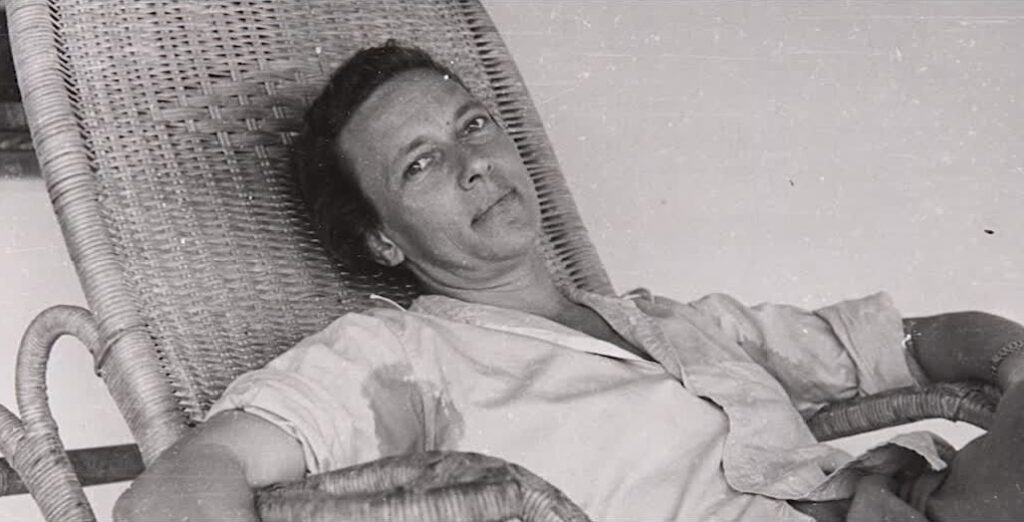

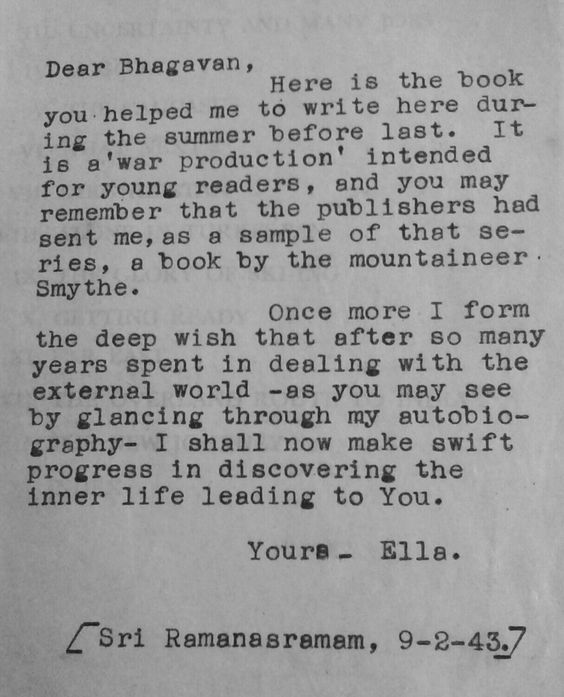

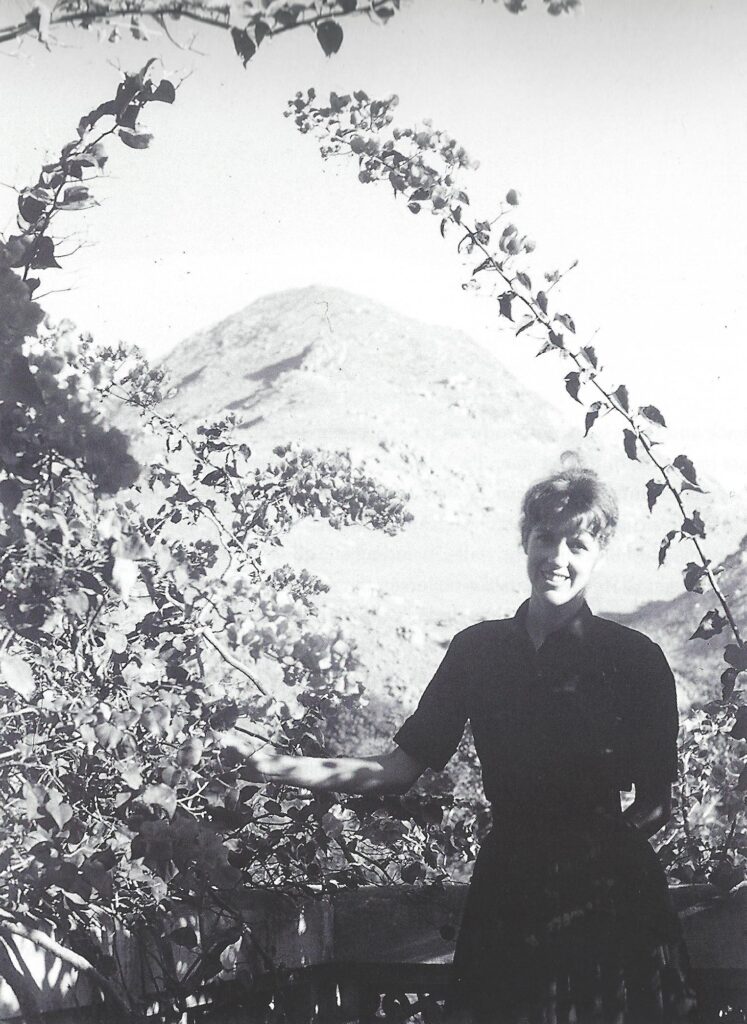

Ella Maillart was a Swiss travel writer and photographer who remained in India from 1939 to 1945 and resided mostly in Tiruvannamalai,

William S. Spaulding Jr of New York City visited Sri Ramana in the 1930s,

Mother of Dr Suzanne Alexandra Curtil Sen, Jeanne Curtil and Suzannes’s daughter Monica arrived in 1940, Monica would attend school in Bangalore but would visit the ashram once or twice a year until 1952,

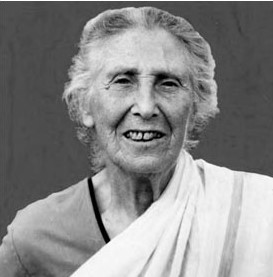

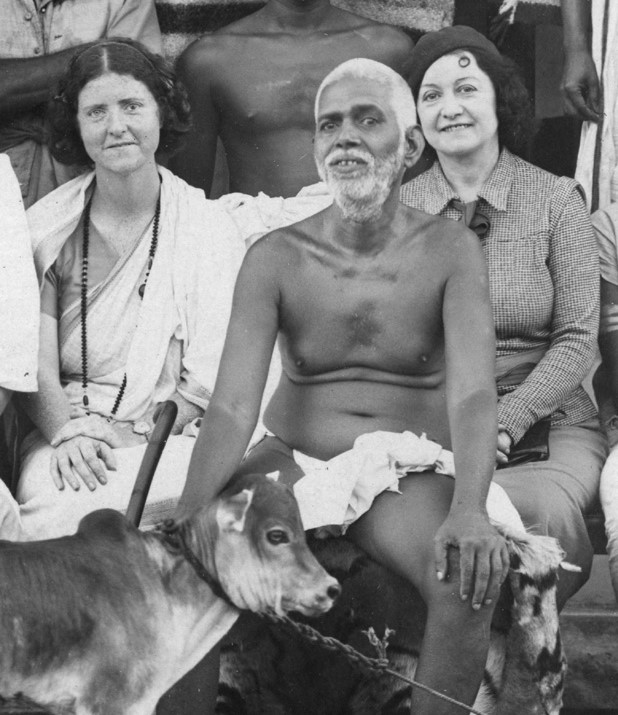

Lucia Osborne with her children Catherine, Frania and Adam, arrived in 1942,

Blanca Schlamm (Atmananda), an Austrian concert pianist in 1942,

William Samuel stayed and sat in the silence with Ramana Maharshi for 14 days in April 1944,

Alexander Phipps (Madhava Ashish) visited in 1944,

Australian travel writer Frank Clune visited in 1944,

Arthur Osborne in 1945,

Osborne’s fellow POW, Dutchman, Louis Hartz would visit after the Second World War,

Georges Le Bot, Private Secretary to the Governor of Pondicherry, and Chief of Cabinet of the French Government visited in December 1945,

British teacher Mr Phillips who was a former missionary and had been in Hyderabad for about 20 years visited in May 1946,

European Mr Evelyn in May 1946,

Mrs Barwell (whose husband was a barrister in Almora), accompanied by Australian Miss Eleanor Harriet Rivett, principal of the Women’s Christian College in Madras, visited in September 1946,

Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) arrived with a party of 25 Polish people, mostly girls in October 1946,

Miss Boman, a Swiss lady who had been in India for about eight years, and was head of the Baroda palace staff of servants, stayed for 4 days in October 1946,

American Robert Adams also stayed for three years from 1947 (disputed as to whether he was ever at the ashram),

Swiss Henri Hartung first came in 1947 for ten days,

American Sam Rappold arrived on the 27th of December, 1947,

Elsa Lowenstern is mentioned in Thelma Rappold’s 1948 diary entry,

a French sannyasin is also mentioned in the same diary who came for Bhagavan’s darshan, leaving France four months previously without any money, stowing away on a French ship bound for India. Barefoot and with nothing to call his own but the clothes on his back, he was making a pilgrimage through India in search of spirituality,

American Thelma Benn (later Rappold) spent nearly three years with Ramana Maharshi from February 1948 until Summer 1950 (her husband Sam Rappold was there for most of this time – these two Americans arrived in India independently, they married in Varanasi before leaving India), her friend from Seattle Mrs Wally Groeger visited her in the ashram in December 1948 and stayed for nearly a year, before going on to meet Swami Ramdas and then later returning to the States,

British national Sangharakshita (Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood) and his Indian friend Buddharakshita arrived in late November 1948, and stayed for six weeks,

American journalist Winthrop Sargeant arrived in 1948 for the Life Magazine article published in 1949,

American Photographer Eliot Elisofon spent two weeks on the ashram in 1948 taking the photos for Life Magazine that were published in 1949 (he made several trips to the ashram),

French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson first visited in 1948, and later in 1950, arriving 10 days before the Maharshi’s mahasamadhi,

Krishna Prem (Ronald Nixon) met Ramana Maharshi in 1948,

two English women from South Africa Gertrude de Kock and Eureka Wessels arrived in 1948 staying for 10 days,

Stanford University professor Frederic Spiegelberg visited Ramana Maharshi sometime between 1948 and 1949,

friends of Eleanor Pauline Noye, Melva Cliff and Ananda Jennings were at the ashram for some weeks in 1949,

Swede Peer Wertin / Per Westin (Swami Ramanagiri) in 1949 and in 1950,

Mieczyslaw Demetriusz Sudowski (Mouni Sadhu) Polish author of spiritual, mystical and esoteric subjects in 1949 for a few months,

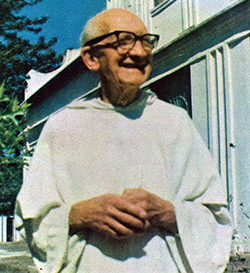

Henri Le Saux (Swami Abhishiktananda) first visited the ashram in January 1949 along with Fr. Jules Monchanin (Parama Arubi Ananda) who was on his third visit,

Dutch teacher and writer Wolter A. Keers was taken to Ramanasramam in 1950 by Roda Maclver, wife of David MacIver,

Miss Eleonore de Lavandeyra in 1950,

American yogini Judith Tyberg (Jyotipriya) stayed for a week sometime between 1947 and 1950.

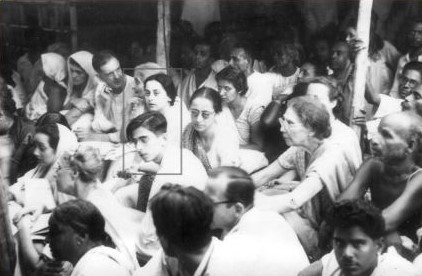

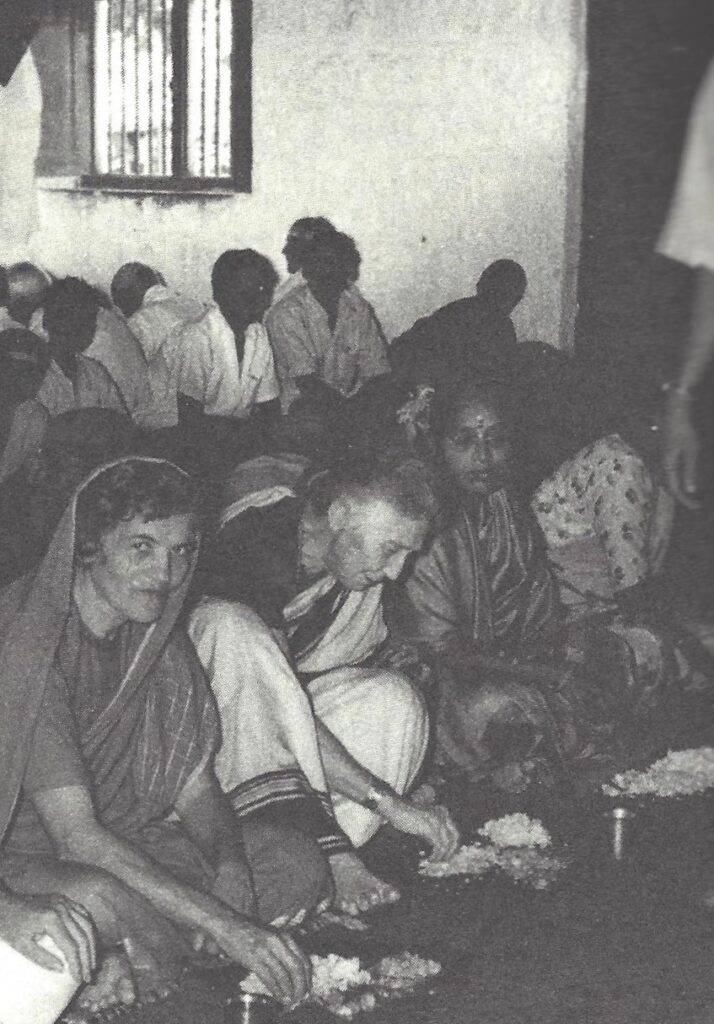

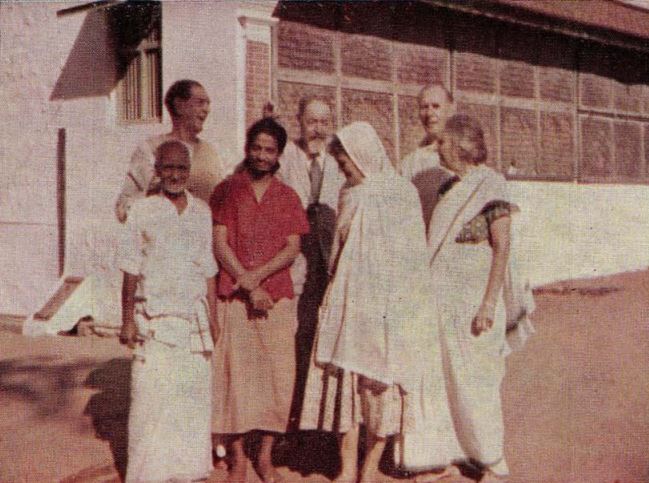

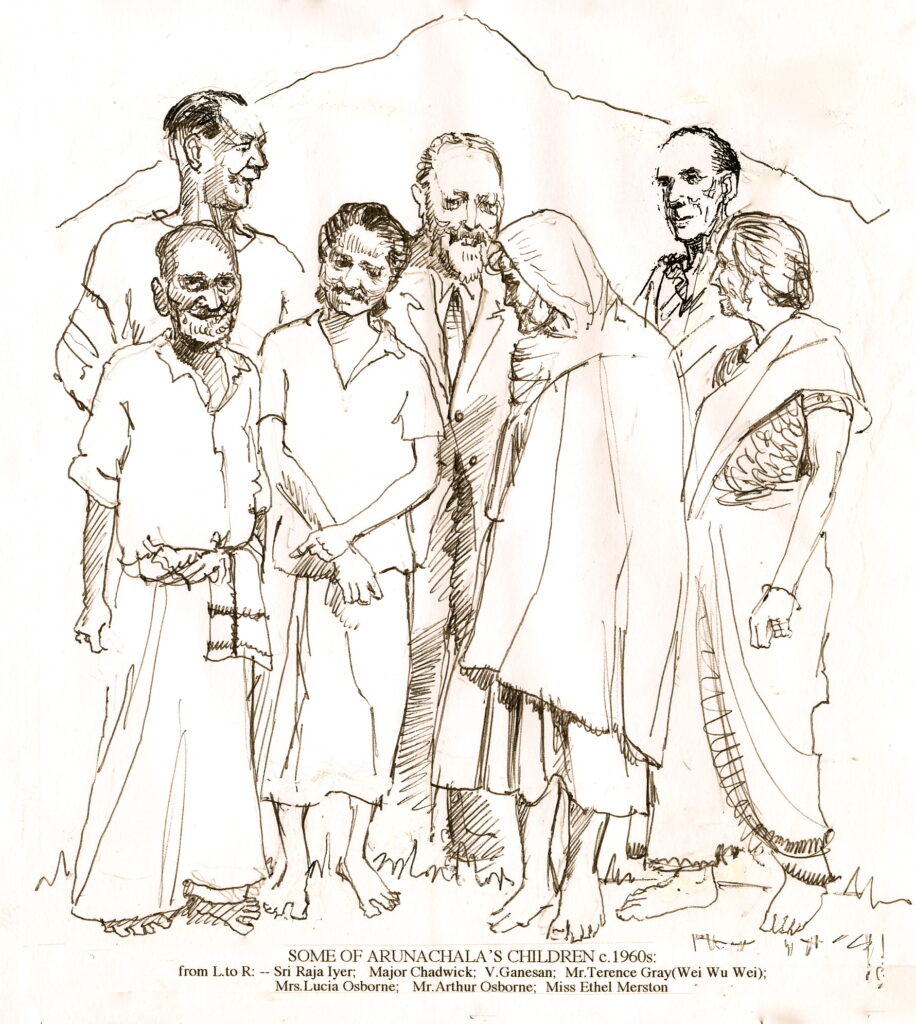

Unidentified Western visitors and devotees of Ramana Maharshi at the end of the article.

https://archive.arunachala.org/ramana/devotees

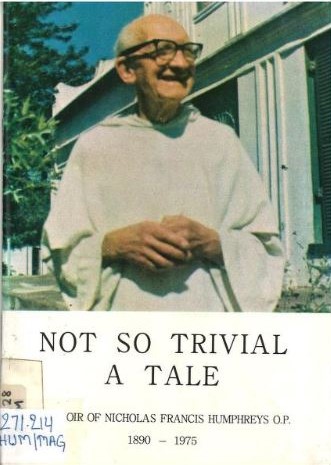

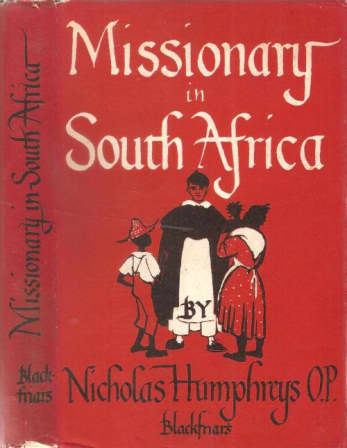

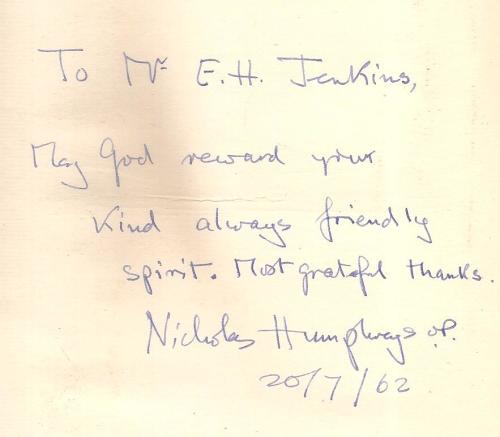

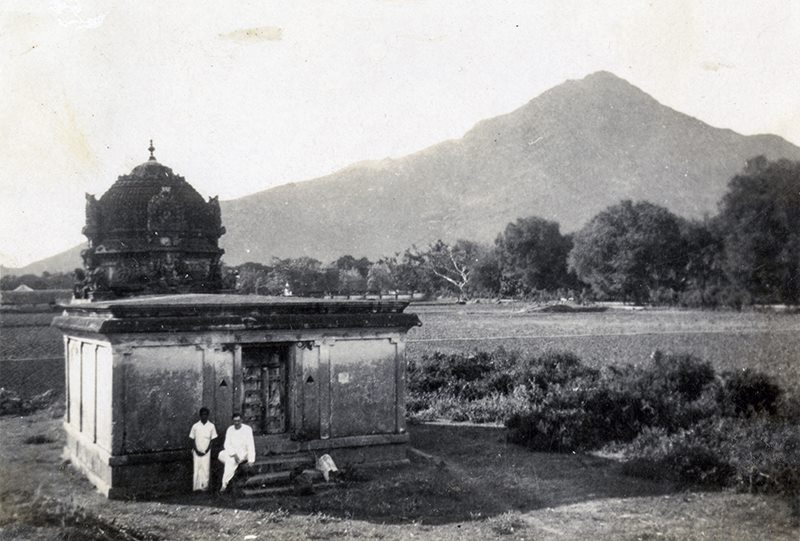

In 1911, Frank Humphreys (Francis Henry Humphreys, later as Nicholas Francis Humphreys), Assistant Superintendent of Police in Vellore, was the first Westerner known to sit in Ramana Maharshi’s presence. He was born in 1890 in London, of High Anglican parents. His father was a struggling physician; his mother was interested in the occult and practiced fortune-telling, table-turning, second sight and later, Spiritualism. He was to contract pleurisy, malaria and suffer numerous other health issues that plagued him throughout his life. He had more than twenty-five serious operations and spent over seven years in hospitals at different times. The 21-year-old British police officer had at least three face-to-face visits with the young Sri Ramana who was at the time living in the Virupaksa Cave. He was brought to meet the Maharshi by S. Narasimhayya (who was a disciple of Sri Kavyakanta Ganapati Muni and a devotee of Bhagavan) and Ganapati Muni. Fortunately, Humphreys recorded some of his experiences, he published the book Glimpses of the Life and Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. The book is based on articles that Humphreys first published in The International Psychic Gazette in 1913. Humphreys was baptised a Catholic (brought up as an Anglican) and took his first vows in the Dominican Order at the age of 37 (14 years after leaving India). He wrote, “I was at home at last, and through the kindness of the Order have been at home ever since.” He took “Nicholas” as his name in religious life. He worked tirelessly for 45 years serving the needy in South Africa, where he died in on September 20, 1975, and was buried at Stellenbosch.

From https://english.sreyas.in/light-of-the-world/ The story of Humphreys itself was unusual. He arrived at Bombay in 1911 on being appointed as an Assistant Superintendent of Police, and within a short time of landing at Bombay fell sick. By then he already had practised yoga and was capable of travelling to any place in the subtle body leaving the gross one. Through his subtle body, Humphreys was able to find a Pandit (Munshi) at Vellore to teach him Telugu. On March 18, the Telugu Pandit, Sarvepalli Narasimham (later, Swami Pranavanada) came to him.

The student began questioning the Munshi about philosophic matters. He also asked the teacher to fetch him books on astrology. The next day when the Munshi came, he asked him if there were any Mahatmas in the vicinity and if he knew any such one. The Munshi probably thought that all talk of a guru to the Englishman was unwarranted and hence replied that he knew no Mahatma. The next day, the student said, “Munshi, you said yesterday that you did not know of any Mahatma but your guru appeared in my dream this morning. In fact, you were the first person of Vellore that I saw even at Bombay.” The Munshi protested that he had never visited Bombay at all. Thereupon, the student told him of the occult powers acquired by him through the practice of yoga. The teacher was impressed and as requested by the student, showed him some pictures of great souls. On seeing Ganapati Muni’s picture, Humphreys exclaimed, “This is the great man who appeared in my dream this morning. Is he not your guru?” Then the Munshi had to acknowledge that Ganapati Muni was indeed his guru.

Within a fortnight, Humphreys fell ill again and had to be moved to Ootacamund. He kept writing to the Munshi every now and then. Once he wrote that he saw a person with matted hair, a long beard and brilliant eyes. On another occasion, he said that he proposed to give up non-vegetarian food to facilitate his practice of pranayama and dhyana. On yet another occasion, he asked whether it would be proper for him to rejoin an esoteric society of which he was a member earlier. After the return of Humphreys from Ootacamund, he and the Munshi joined Ganapati Muni in November 1911 on a visit to the Maharshi. In his very first question posed to Bhagavan, his struggle as a youth, his high ideals and his desire to help others were revealed. The Maharshi also spoke to him partly in English.

Humphreys: Swami, can I do anything to reform the world?

Maharshi: You reform yourself first. It is as good as reforming the world.

Humphreys: I wish to do good to the world, will I not be able to do it?

Maharshi: You do good to yourself first, after all you are also part of the world. Not only that, you are the world, the world is you. Both are not apart.

Humphreys (after a pause): “Swami, will I not be able to perform any miracles like Krishna, Jesus and the like?

Maharshi: Did those people think that they were performing miracles while doing those acts?

Again after a pause Humphreys replied in the negative. Maharshi perhaps thought that interest in such

powers would cause harm to Humphreys and warned him that the only thing to be obtained was the atma and that he should devote all his energies towards that end. He added that Humphreys should work towards the goal with an attitude of complete self-surrender.

Bhagavan once described Arunachala as a unique hill of light, so was he. Those who visited him once were bound to return over and over again. Humphreys paid a visit to Bhagavan a second time. In the midday hot sun, he travelled all the forty miles from Vellore on a motor cycle to Tiruvannamalai and there, picking up Raghavachari, a P.W.D. Supervisor, paid a visit to Bhagavan. He was tired and dust-laden; on seeing him, Bhagavan offered him some refreshments and quietened him. At that moment, the District Munsiff A.S. Krishnaswami Iyer was also there. With both Raghavachari and Krishnaswami acting as interpreters the conversation proceeded.

Humphreys: Swami, I easily forget the lessons, only the last words remain in my memory. What should I do?

Maharshi: You can attend to your duty as well as to your meditation.

Humphreys had Bhagavan’s darshan a third time. By then his regard for him had reached such a level that he considered it sacreligious to climb the hill with his shoes and hat on. So, he discarded them and reached the cave barefoot. Bhagavan while returning to the cave from somewhere saw Humphreys’ belongings on the way and asked Palaniswami, who was with him, to pick them up. No one knew what instructions Bhagavan gave Humphreys on that occasion.

Humphreys wrote a letter to his friend in England, detailing his visits to Bhagavan and the instructions he received. The friend, Felix Rudols, put it in the form of an article and got it published in the International Psychic Gazette. Later, that article was translated into several other languages and seekers of various lands benefited from the instructions of Bhagavan. Much later, the Englishman quit his job and became a monk of the Roman Catholic Church.

Glimpses of the Life and Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi https://realization.org/p/frank-humphreys/temp/glimpses.html

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Face_to_Face_with_Sri_Ramana_Maharshi.pdf

Download: Not So Trivial A Tale : Memoir of Nicholas Francis Humphreys O.P. 1890 – 1975 https://archive.org/details/not-so-trivial

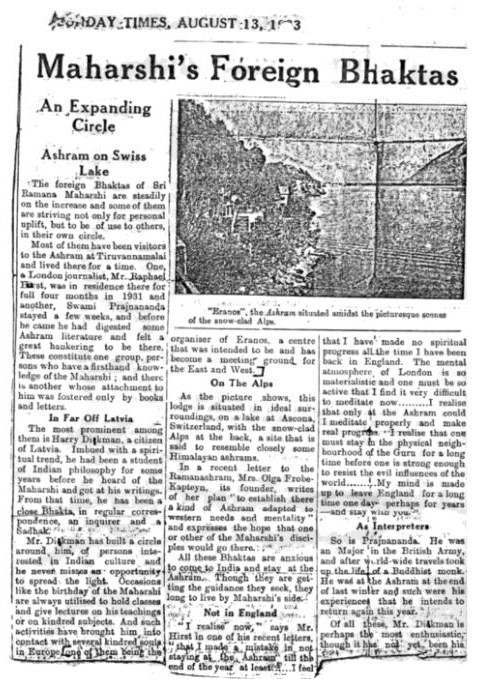

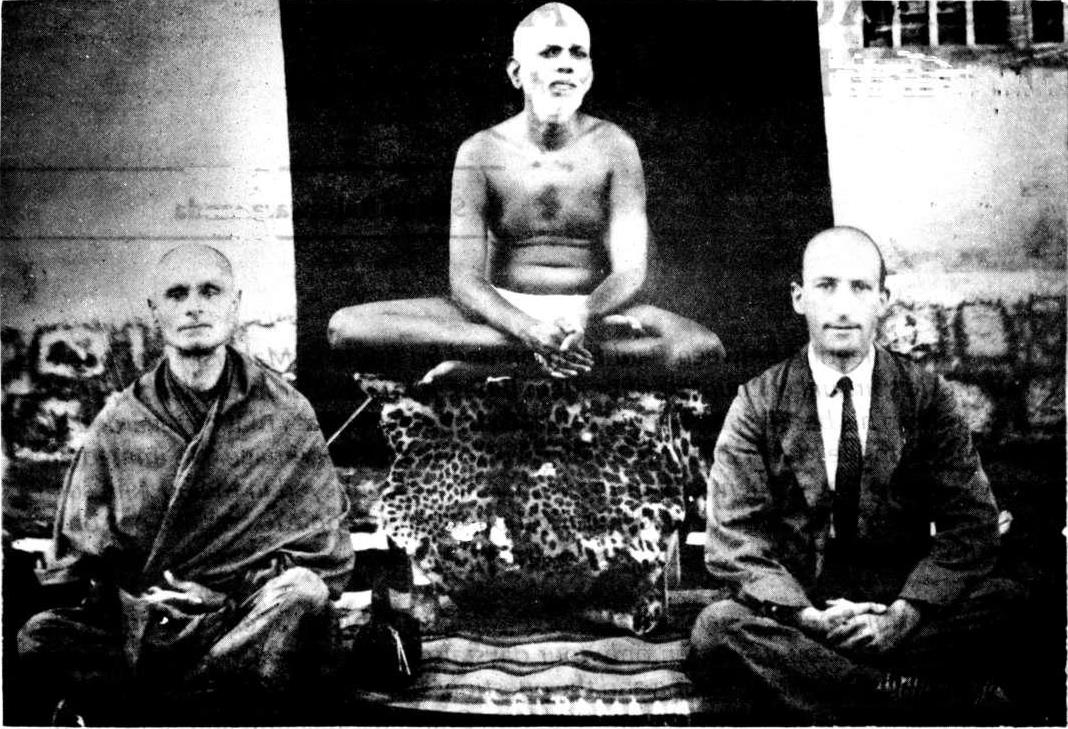

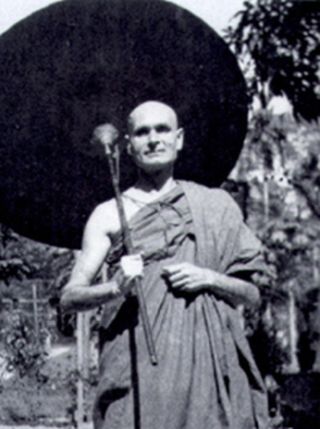

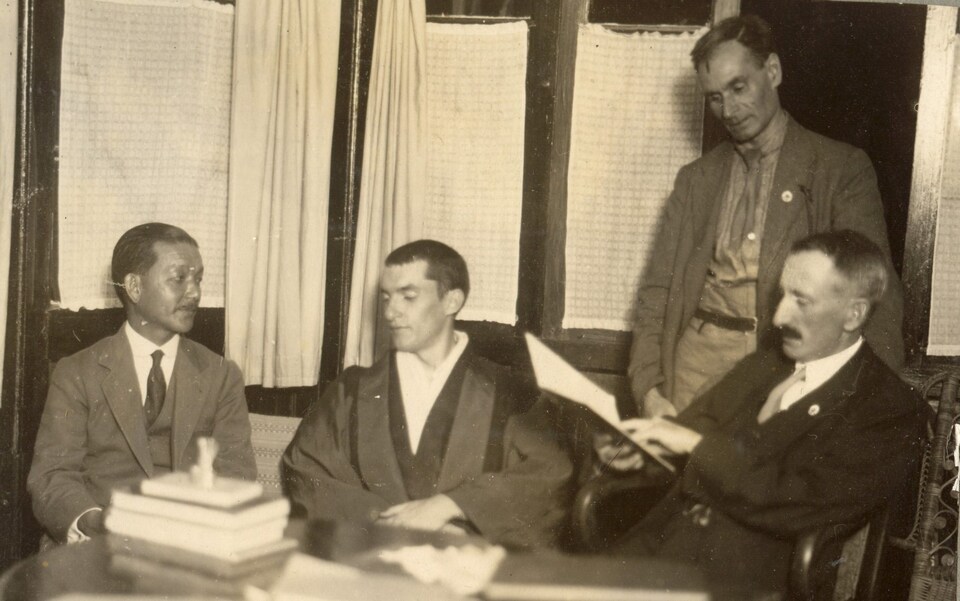

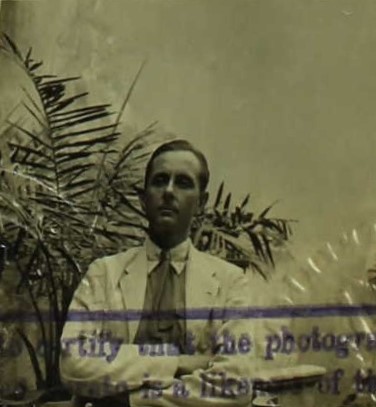

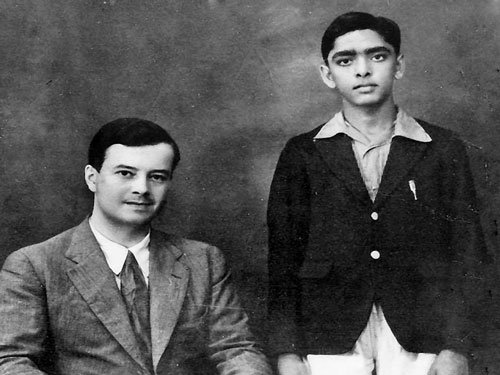

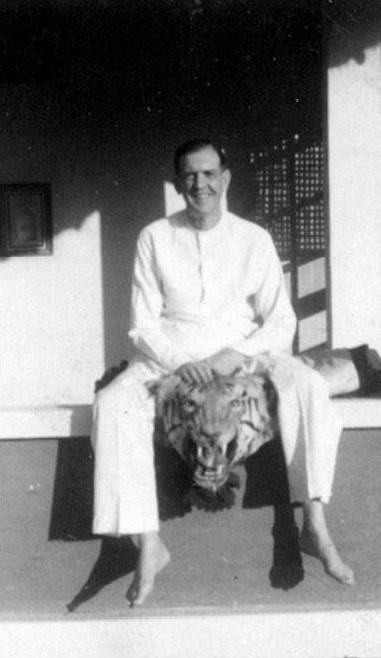

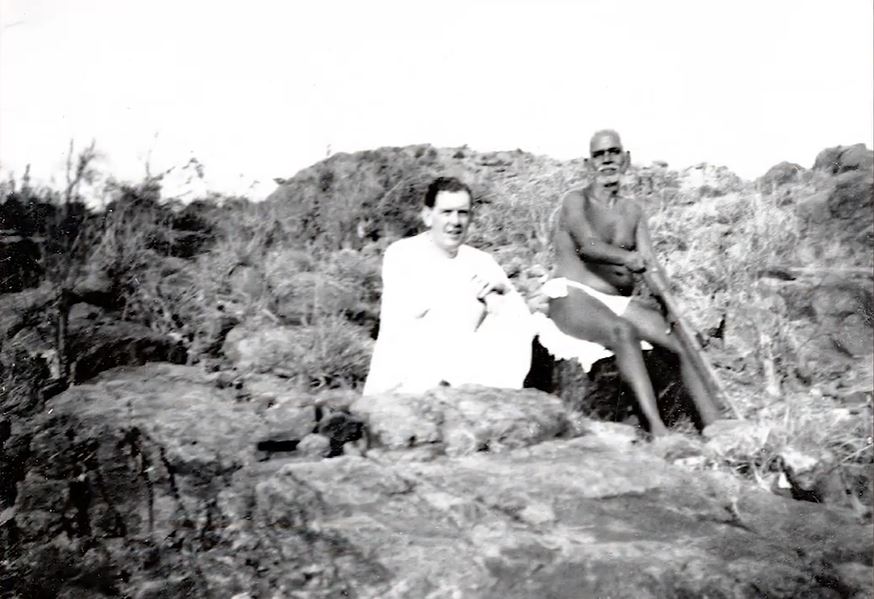

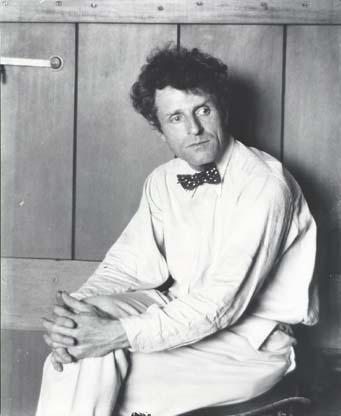

Among the first Westerners to come and stay at the ashram were Paul Brunton (the pen name of Raphael Hurst) (21 October 1898 – 27 July 1981) and Bhikshu Prajnananda (former military Frederick Fletcher officer known later as Swami Prajnananda, founder of the English Ashram in Rangoon) who lived in a two-room cottage to the north of the tank in Palakothu. Brunton, who arrived in 1931, was a British philosopher, mystic and traveller who had left a journalistic career to live among the yogis, mystics and holy men to study Eastern and Western esoteric teachings. He has been credited with introducing Ramana Maharshi to the West through his books A Search in Secret India published in 1934 and The Secret Path published in 1935.

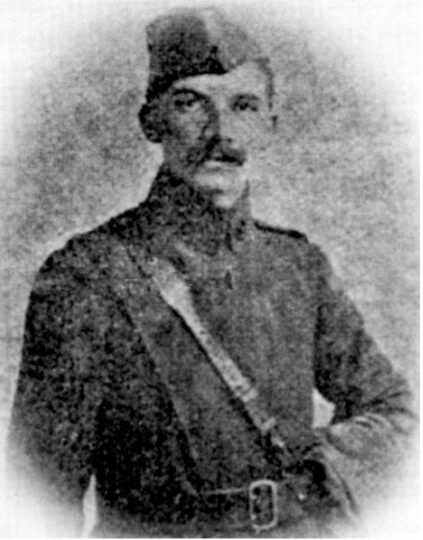

Bhikshu Prajnananda was an Englishman and an Oxonian, his earlier name was Frederick Fletcher. He mastered several European languages and was a commander of the armed forces during the world war. The immense destruction and loss of life during the war touched him, repelled by the slaughter he eventually gave up his military career and became more inward looking. He embraced Buddhism and became a bhikku (monk).

In 1932, he spent two months at Ramanasramam and heard Bhagavan’s teachings in person. He profited greatly by them and developed a reverential attitude towards Bhagavan. He remained in touch through correspondence seeking Bhagavan’s advice on matters spiritual. He would also write to his friends extolling Bhagavan’s divine qualities. In the Sunday Express of 28th of May 1933, there is an article about him ~ HAR Men with the Elixir of Life by Rhy Darby.

Maud Alice Piggott (1877 – 1974) was born in England, traveled to India several times, but ultimately settled down in Hollywood, California where she passed away on August 19th, 1974 at eighty-seven. She joined contemporaries such as Douglas Ainslie (Grant Duff), Sunyata, Anagorika Govinda, Pauline Noye, W. Y. Evans-Wentz, who also earlier in life had had some association with Ramana Maharshi and for one reason or another migrated to or lived in California. At that time California was an incubator for spiritual discovery and intellectual openness that attracted scores of seekers looking for new approaches to inner and outer fulfillment.

Records show that in the beginning of January 1935 she first visited the ashram for a few days and then returned from Madras before the end of the month prepared for a longer stay. That is when she befriended an American visitor, Y.W. Evans-Wentz, the Tibetan translator of The Life of Milarepa, The Tibetan Book of the Dead and others works. They discussed spiritual matters and she took courage from him to question Bhagavan further until she was satisfied. Dr. Evans-Wentz himself asked many pertinent questions, especially useful for Westerners seeking enlightenment. Fortunately these questions and answers, and much of Maud Piggott’s dialogues, were diligently recorded in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi for posterity.

Maud Alice Piggot is believed to have been the first English lady to visit Sri Ramana Maharshi.

“I have visited India before, but my first visit off the beaten track was in 1932-33. It was my wish to meet one of the holy men of India, but so far it had been a vain one. Then I was told of Ramana Maharshi. The friend who gave me the welcome news offered to take me to him, and so we arrived at Tiruvannamalai.

He was seated on a divan in front of which sandal sticks were burning. About a dozen people were present in the hall. I sat across-legged on the floor, though a chair had been thoughtfully provided for me. Suddenly I became conscious that the Maharshi’s eyes were fixed on me. They seemed literally like burning coals of fire piercing through me. Never before had I experienced anything so devasting – in that it was almost frightening. What I went through in that terrible half hour, by way of self-condemnation and scorn for the pettiness of my own life, would be difficult to describe.

When we returned for the evening meditation, the hall was compellingly still. The eyes of the Holy One blazed no more. They were serene and inverted. All my troubles seemed smoothened out and difficulties melted away. Nothing that we of the world call important mattered. Time was forgotten.

For that time onwards started a routine that was to be the same for many weeks. The rickety cart would turn up at six in the morning. It took me to the Ashram and came back again for the evening journey. I soon acquired a technique of the balance that promised safety in the cart. I was given a small hut, seven feet by seven, for my use during the day; the Ashram did not provide night accommodation for ladies in those days.

Among those who had turned up at the Ashram was the well-known author, Paul Brunton. We had many enlightening talks. Asking questions in the open hall was rather an ordeal, but backed by him I lost some of my diffidence. An interpreter was always on hand; for although the Maharshi understands English he does not speak it with ease. He knows immediately, however, whether the exact shade of meaning has been accurately translated, and if not, he perserves until one has understood him completely.”

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Face_to_Face_with_Sri_Ramana_Maharshi.pdf

American social psychologist, Professor Pryns Hopkins (Prynce Hopkins) visited Sri Ramana after reading about him in Paul Brunton’s A Search in Secret India (Originally published January 1, 1934).

Prynce Hopkins (March 5, 1885 – August 16, 1970), who was born Prince Charles Hopkins, was an American Socialist, pacifist, philanthropist, and author of numerous psychology books and periodicals. He was jailed and fined for his strident anti-war views, pro-union activities, and investigated for his associations with such social reformers as Upton Sinclair and Emma Goldman.

A Talk with Ramana Maharshi by Pryns Hopkins.

In as much as India is notoriously the most metaphysically minded of all countries, it was natural that I should seek discussions in this field.

Ever since I had read Paul Brunton’s A Search in Secret India, I had been keen to visit Ramana Maharshi, the sage whom Brunton found most impressive of all those he sought out. Soon after my arrival at his Ashram, I bade one of the two men who mainly ministered to him to inquire whether I might ask of him two questions. Accordingly, I was requested to take my seat in front of the group of visitors and an interpreter sat next to me (although the Maharshi usually gets queries directly through English) and was invited to present my question.

The first of these questions was: “If it is true that all the objective world owes its existence to the ego, then how can that ego ever have the experience of surprise as it does, for example, when we stub our toe on an unseen obstacle?”

Sri Bhagavan answered, “The ego is not to be thought of as antecedent to the world of phenomena, but rather that both rise or fall together. Neither is more real than the other. Only the non-empirical Self is more real. By reflecting on the true nature of the Self, one comes at length to undermine the ego. At the same time one realizes that the material obstacle and the stubbed toe are equally unreal, and one learns to dwell in the true Reality which is beyond them all.”

He then went on to outline that we only know the object at all through the sensations derived from it remotely. Moreover, physicists have now shown that in place of what we thought to be a solid object there are only dancing electrons and protons.

I replied that while we have, indeed, direct knowledge only of sensations, we know less, for all that knowledge, about the objects which give rise to the sensations, about which knowledge is checked continually by making predictions, acting on them and seeing them verified or disproved. Furthermore (here I went on to my second query), “If the outer phenomena which I think I perceive have no reality apart from my ego, how is it that someone else also perceives them? For example, not only do I lift my foot higher to avoid tripping over that stool yonder, but you also raise your foot higher to avoid tripping over it too. Is it by a mere coincidence that each of us independently has come to the conclusion that a stool is there?”

Sri Maharshi replied that the stool and our two egos were created by one another mutually. While one is asleep, one may dream of a stool and of persons who avoided tripping over it just as persons in waking life did, yet does that prove that the dream stool is any more real? And so we had it back and forth for an hour, with the gathering very amused, for all Hindus seem to enjoy a metaphysical contest.

During that afternoon’s darshan I again had the privilege of an hour’s talk with the Maharshi himself. Observing that he had given orders to place a dish of food for his peacock, I asked, “When I return to America would it be good to busy myself with disseminating your books to the people just as you offer this food to the peacocks?” He laughed and answered that if I thought it good it would be good, but otherwise not. I asked whether, quite apart from whatever I thought, wouldn’t it be useful to have pointed out a way to those who were ripe for a new outlook? He countered with, “Who thinks they are ready?”

The Maharshi went on to say that the essential thing is to divorce our sense of self from what our ego and our body are feeling or doing. We should think ‘feelings are going on, this body is acting in such and such a manner,’ but never ‘I feel, I act.’ What the body craves or does is not our affair.

I then asked, “Have we then no responsibility at all for the behaviour of our ego?”

He replied, “None at all. Let it go its own way like an automaton.”

“But,” I objected, “you have told us that all the animal propensities are attributes of the ego. If when a man attains jivanmukti he ceases to feel responsibility for the behaviour of his ego and body, won’t he run amok completely?” I illustrated my point with the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Maharshi replied, “When you have attained jivanmukti, you will know the answer to those questions. Your task now is not to worry about them but to know the Self.”

But I am forced to doubt the whole theory unless it explains away this discrepancy: “Here before us is the Maharshi who has attained jivanmukti and so withdrawn from all responsibility for the conduct of his ego and the body we see before us. But though he declares them to be the seat of all evil propensities, his ego and body continue to behave quite decorously instead of running wild. This forces me to suspect that something in the hypothesis is incorrect.”

He answered, “Let the Maharshi deal with that problem if it arises and let Mr. Hopkins deal with who is Mr. Hopkins.”

Dr Pryns Hopkins (1885-1970) was a resident of Santa Barbara, California, a scholar of psychology, an enthusiastic follower of Freud, a world traveller, philanthropist, founder of two progressive schools and author of many books. He inherited wealth and spent it generously on social programs and organizations. During his travels he met with the great thinkers and political kingpins of his day, including Winston Churchill, Hitler and Freud. He was the son of distinguished parents, whose history traces back to the founding fathers of the nation.

Prynce Hopkins, christened Prince Charles Hopkins, spelled his name Pryns from about 1921 to 1948, and thereafter Prynce, he was a wealthy Californian described by the several newspapers as a “socialist millionaire.” He had inherited a good deal of stock in the Singer Sewing Machine company, which his father, Charles Harris Hopkins, obtained from his second wife, Ruth Merrit Singer, after she died in childbirth. (Prynce was the only child of Charles’ third wife, Mary Isabel Booth.) In 1913, Charles Hopkins died and left Prynce $3 million. Mary received $3 million. Prince’s brother, George P. Hopkins, who was a millionaire in his own right, received $100,000. Prynce used his money to fund leftist causes, which he labelled the “uplift movement,” and self-publish books on psychoanalysis, social reform, and religion.

Hopkins obtained his BA from Yale, a Master’s degree in education from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. from London University in psychology. He lived in England and France, where he owned and ran a school for boys based on Montessori-like methods, from 1921 to England’s entrance in WWII in 1939. During the 1940s, while living in Pasadena, California, and publishing a socialist journal titled Freedom, he lectured on comparative religion at Pomona College.

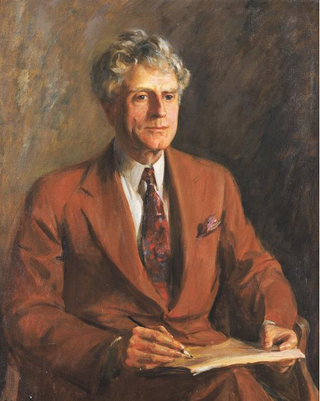

Grant Duff (Douglas Ainslie) (1866 – 1948) first visited the ashram in January 1935. A distinguished Scottish diplomat, poet, world traveller, philosopher and above all, a sincere seeker of Truth. Duff studied life and literature intensely for decades before he discovered in Ramana Maharshi, the ultimate aim and purpose of life personified.

Duff must have spent at least a year in India on this visit, which he could never repeat in spite of writing in the 1940s that he was hoping to fly to India soon. While in India, besides visiting the Maharshi at least three times, he studied Sanskrit in Ootacamund for six months.

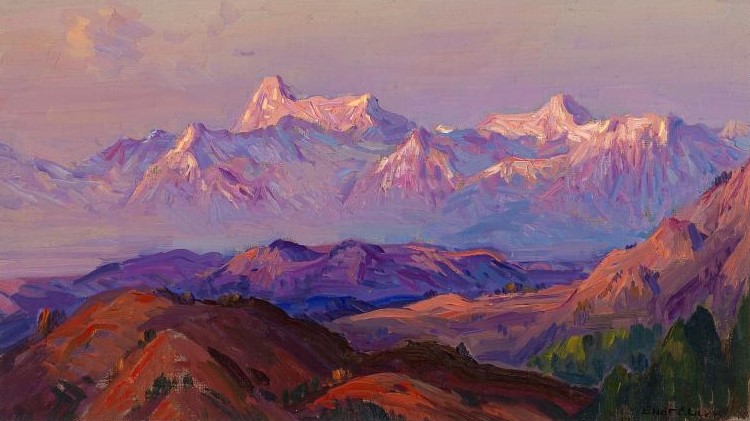

It is interesting that two other foreigners that he met at Ramanasramam in 1935, Maud Piggott from England and Evans-Wentz from Florida, all spent the last decade of their lives in close proximity to each other in California along with Lama Govinda (Lama Anagarika Govinda (1898-1985), born Ernst Lothar Hoffmann. During the later part of his life, the Lama and his wife Li lived on the Evans-Wentz estate in the Kumaon Himalaya and finally in a small house in Marin County, California. Li Gotami was Parsi artist from Bombay and had been his student at Santiniketan in 1934, they married in 1947).

From The Mountain Path October 1974 – Grant Duff writes – Mark my words. I do not know what happened when I saw Maharshi for the first time, but the moment he looked at me, I felt he was the Truth and the Light. There could be no doubt about it, and all the doubts and speculations I had accumulated during the past many years disappeared in the Radiance of the Holy One.

It is very difficult to describe in words the unanticipated change that came over me. Suffice it to say that though my visits to the Ashram were brief, I felt that every moment I was there I was building up within me what could never be destroyed, whatever may happen to this body and mind.

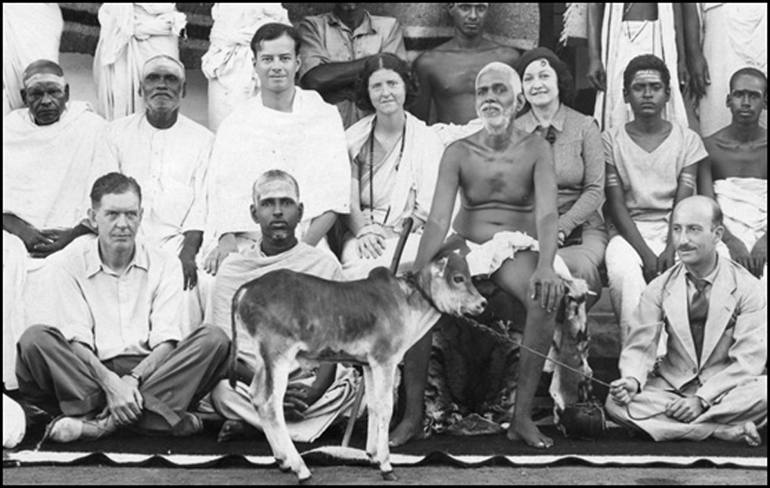

German born American Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz (1878 – 1965) pioneered the study of Tibetan Buddhism, mostly known for publishing an early English translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead in 1927, Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa (1928), Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines (1935), and The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation (1954), visited Ramana Maharshi in 1935. In 1946, he wrote the preface to Yogananda’s well known Autobiography of a Yogi. He stays for two weeks on the ashram in 1935.

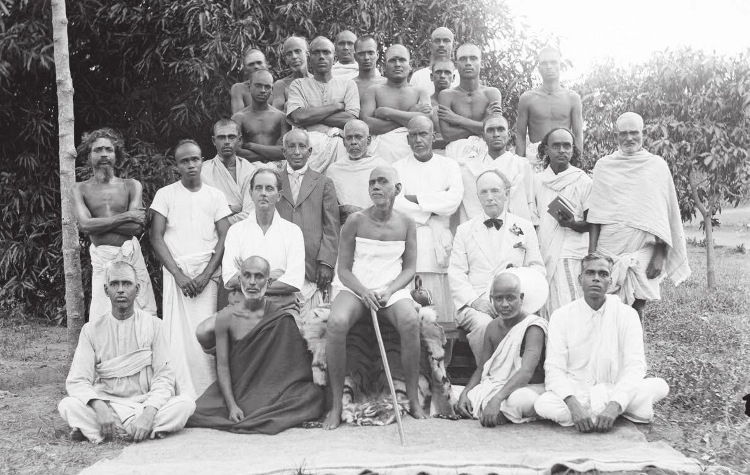

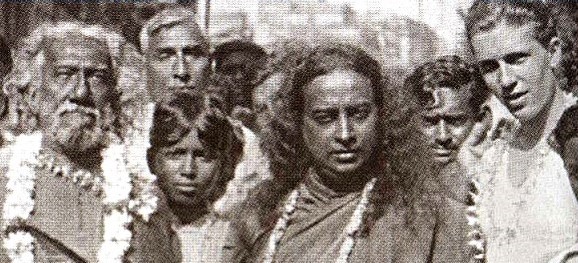

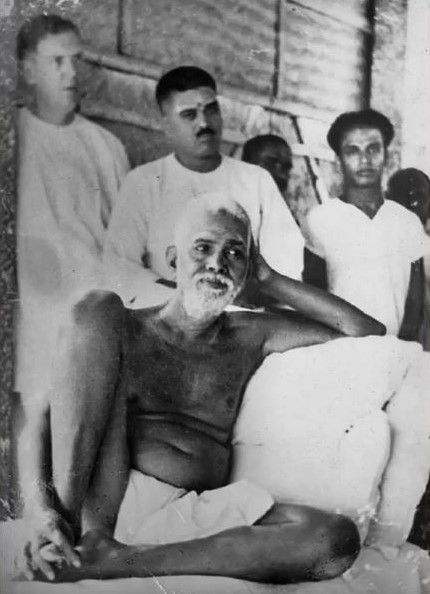

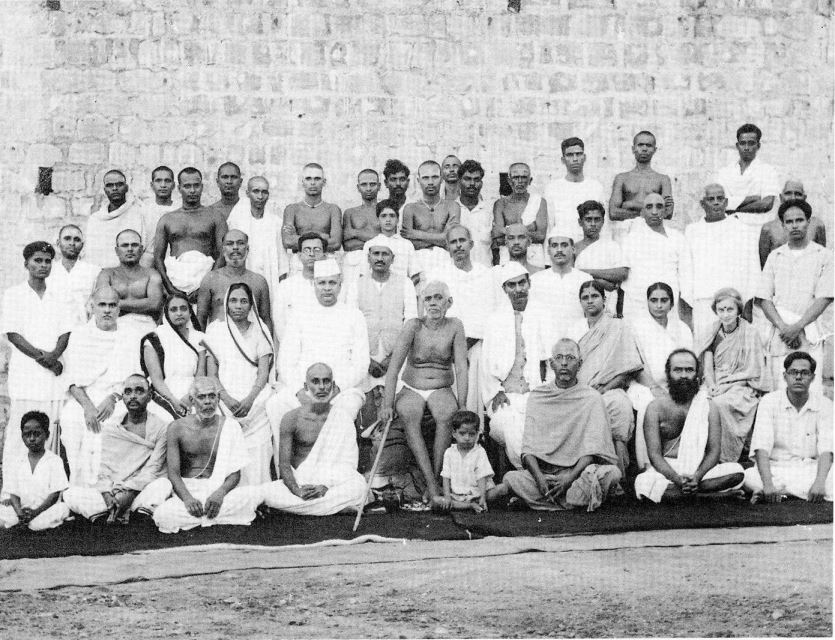

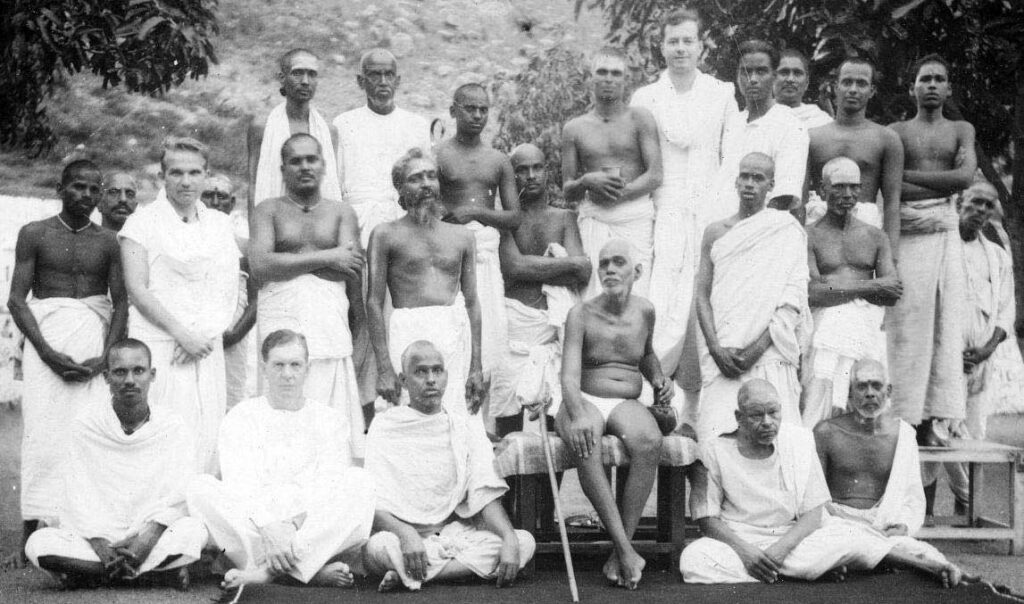

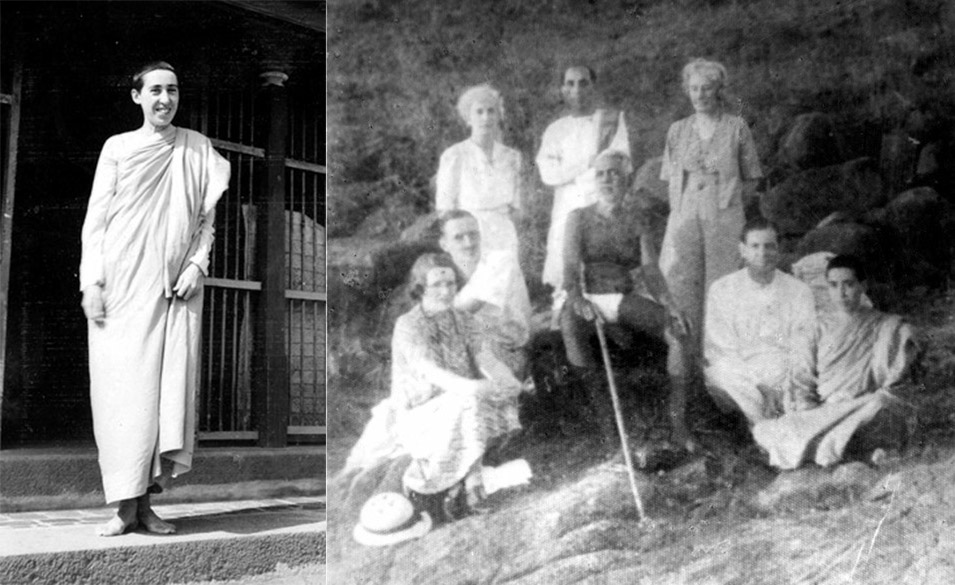

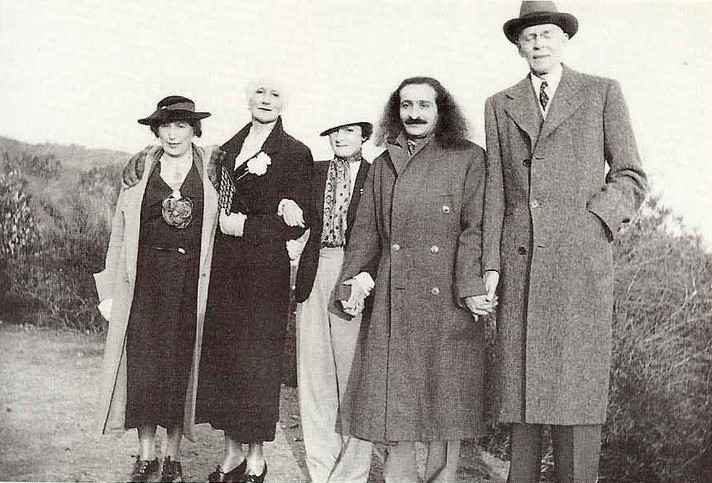

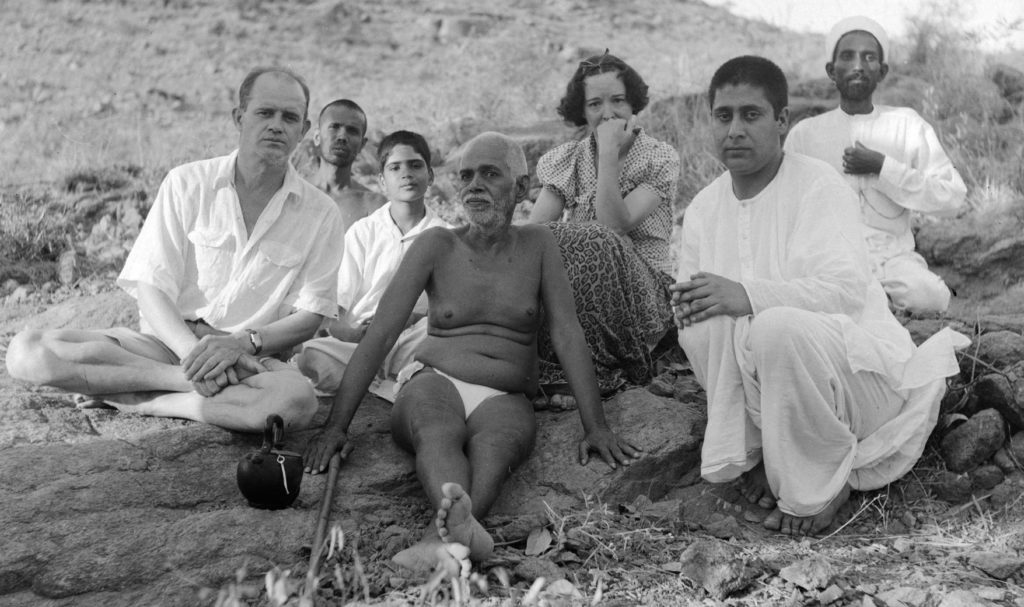

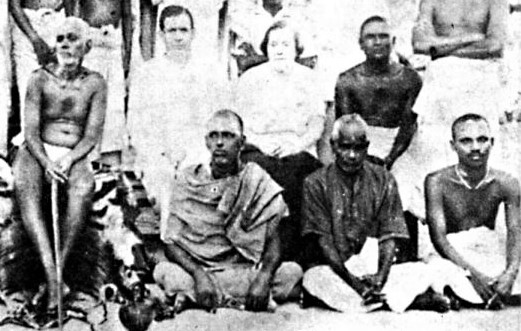

Swami [Chinnaswami]; 2. (in front) Yogi Ramiah; 3. (behind) Dr. W.Y. Evans-Wentz; 4. Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi;

5 (behind) Grant Duff (Douglas Ainslie); 6. (front) Munagala Venkataramiah (compiler of Talks). 7. Sub-registrar

Narayana Iyer; Standing; middle row: 1. Nondi Srinivasa Iyer; 2. Krishnamurti (office attendant); 3. Somasundara

Swami (Book-Depot); 4. K.R.V. Iyer (Calcutta); 5. Sama Iyer; 6. Ganapati Shastri (Head Accountant; Taluk Office); 7.

Vishwanatha Swami; 8. T.K. Sundaresa Iyer; 9. Father of Ranga Rao; Standing; back row: 1. Rangaswami (Attendant);

(behind) & 3. Unidentified; 4. Ramaswami Pillai; 5. Ramakrishnaswami; 6. Subramaniam Swami; 7. Kumaraswami

(Stores); 8. (behind) Ranga Rao (Cook); 9. (in front) Unidentified; 10. Annamalai Swami; 11. Madhava Swami. Photo: The Mountain Path 1994.

American Chemist Dr Bernhard Bey in 1935.

From Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi 15th October, 1935. Talk 81. Dr. Bernhard Bey, an American Chemist who had interested himself in Vedanta for the last twenty years, now in India, came on a visit to the Master. He asked: “How is abhyasa to be made? I am trying to find the Light.” (He himself explained abhyasa as concentration = one-pointedness of mind.)

The Master asked, what was his abhyasa till now.

The visitor said he concentrated on the nasal base, but his mind wandered.

M.: Is there a mind?

Another devotee gently put in: The mind is only a collection of thoughts.

M.: To whom are the thoughts? If you try to locate the mind, the mind vanishes and the Self alone remains. Being alone, there can be no one-pointedness or otherwise.

D.: It is so difficult to understand this. If something concrete is said, it can be readily grasped. Japa, dhyana, etc., are more concrete.

M.: ‘Who am I?’ is the best japa.

What could be more concrete than the Self? It is within each one’s experience every moment. Why should he try to catch anything outside, leaving out the Self? Let each one try to find out the known Self instead of searching for the unknown something beyond.

D.: Where shall I meditate on the Atman? I mean in which part of the body?

M.: The Self should manifest itself. That is all that is wanted.

A devotee gently added: On the right of the chest, there is the Heart, the seat of the Atman.

Another devotee: The illumination is in that centre when the Self is realised.

M.: Quite so.

D.: How to turn the mind away from the world?

M.: Is there the world? I mean apart from the Self? Does the world say that it exists? It is you who say that there is a world. Find out the Self who says it.

Two American ‘students’ accompanied Paramahansa Yogananda on his return trip to India, Mr. C. Richard Wright, and an elderly lady from Cincinnati, Miss Ettie Bletsch. The entourage visited Ramanasramam in 1935.

Buddha Bose was born in 1913, in Sri Lanka, while his Indian father and English mother were en route from London to Calcutta. His mother would only stay in India for 5 years before returning to London, leaving young Buddha behind. He grew up in the Garpar area of Calcutta, a block from the Ghosh home where Yogananda and Bishnu lived. Buddha married into the family of Bishnu Ghosh and Yogananda.

Maurice Frydman (1894 – 1976) came across Brunton’s book A Search in Secret India after moving to Paris sometime in 1928, and eventually arrived in India and the ashram in 1935. He lived in India for decades and was also known as Bharatananda. He was a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi and lived in his ashram, where he made the spinning wheel that Gandhi used. He was close to Nehru, and was associated with Sri Ramana Maharshi and J. Krishnamurti. He was also a long-time friend of Nisargadatta Maharaj, who considered him a Jnani. Frydman edited and translated Nisargadatta Maharaj’s recorded conversations into the 1973 book I Am That. When he died in 1976 in Bombay, India, Nisargadatta was by his bedside. During his last days of life Frydman gets a visit by a professional nurse he does not know. The nurse had been visited in a dream by an old man in a loin cloth telling her to go and take care of Frydman. Frydman refuses to accept the nurse’s offer. As the nurse is leaving she walks past a picture of the old man that had visited her in her dream. Upon telling Frydman this, he accepts her offer and allows her to take care of him. The picture: it was Ramana Maharshi who had left his body over three decades prior. In an article that Maurice wrote very late in his life, he lamented the fact that he didn’t fully appreciate Ramana Maharshi’s teachings and presence while he was alive.

From Death Must Die : Based on the Diaries of Atmananda by Ram Alexander – Maurice Frydman was a Polish engineer who spent most of his life in India. He was in the inner circle of Krishnamurti; however today he is best remembered as the discoverer of Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj (died 1981), a great Maharashtrian jnani who lived in a poor section of Bombay. Frydman thought so highly of him that he learned his dialect and was the editor and translator of a collection of his discourses called I am That. The book attracted many serious seekers, both Indian and foreign, to Sri Nisargadatta in the 1970s.

From Ramana Periya Puranam (Inner Journey of 75 Old Devotees) by V. Ganesan, grand nephew of Sri Ramana Maharshi – Once, I went to Nisargadatta Maharaj´s house because he had asked me to stay with him. I stayed there for eight days. In the morning, from eight to ten, he would ask me to be seated while he did pooja. There were photographs of saints such as Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, the Buddha, Jesus Christ, Ramana Maharshi, and yes, even Maurice Frydman, in his room. Maharaj would apply sandal, vermillion powder and perfume to the photographs and garland them. As he was doing this ritual one day, I was asking myself, “Why is he doing this?” He turned to me and said in a compassionate tone, “Maurice Frydman was a jnani. He was a saint, a sage.”

Author David Godman writes, Maurice Frydman is one of most extraordinary people I’ve ever come across and virtually nothing is known about him. And because of his connection with Ramana Maharshi, Krishnamurti, Gandhi, Nisargadatta, the Dali Lama I kind of view him in my own mind as a Forest Gump of 20th century spirituality. He was in all the right places in all the right times to get the maximum benefit of interaction with some of the greats of Indian spirituality… He was a Gandhian, he worked for the uplift of the poor in India, he worked with Tibetan refugees, he edited extraordinary books [like] “I am That,” probably one of the all time spiritual classics.

This man for me a shining beacon of how devotees could and should be with their teachers. He was just absolutely an extraordinary man. And went out of his way to cover his tracks; to hide what he actually had accomplished in his life. So I’ve enjoyed the detective work of looking in obscure placers, digging out stuff that he personally tried to hide, not because it was embarrassing, but because he didn’t like to take credit for what he’d done. So I see this as an opportunity to wave the Maurice flag and say “look look, this is one of the greatest devotee, sadoc seekers from the West whose been to India in the last 100 years, and I think more people should know about him.”

Dr M. Sadashiva Rao writes, Maurice “Bharatananda” Frydman: The great karma yogi you never heard of…

“We ripen when we refuse to drift, when striving ceaselessly become a way of life, when dispassion born of insight becomes spontaneous. When the search ‘Who Am I?’ becomes the only thing that matters, when we become a mere torch and the flame all important, it will mean that we are ripening fast. We cannot accelerate that ripening, but we can remove the obstacles of fear and greed, indolence and fancy, prejudice and pride.”

You might have come across his name on the cover of the classic giant I Am That. He was the man who tape recorded conversations in the Marathi dialect with Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj and then translated and pushed to publish the book. What you might not know is that he carried out that deed late in his life after five decades of service to India directly and to the world of spiritual seekers at large. The people that he came across and was in deep relationship with included J. Krishnamurti, Sri Ramana Maharshi, Mahatma Gandhi besides Maharaj. Furthermore, he was also involved with the liberation of India from English rule in the state of Aundh by writing the constitution there, as well as being active in the villages of the state. Later on, he spent years pushing the Indian government for and receiving land and money to create the settlements where thousands of uprooted Tibetans escaped the Chinese invasion.

Maurice Frydman was born in the Jewish ghetto of Krakow, Poland in 1894. Being an exceptionally bright student, he excelled in school and studied electrical engineering. He was fluent in Hebrew, English, French, Russian, German and added to that Hindi later in life. His seeking started at a young age and involved delving into Judaism and studying the Talmud. He followed this by becoming a monk in the Russian Orthodox church. This path did not free his thirst and he was said to have been fed up with all dogmas. His brilliance in his school did pave the way for him to drastically change his life from his humble beginning. He had many patents to his name, by the age of twenty when he moved to Europe for his studies and started work.

During this time he came across his first teacher J. Krishnamurti in Switzerland. This meeting was prior to Krishnamurti’s break with the Theosophical Society and the relationship lasted many decades. Maurice was known to be a fierce debater with Krishnamurti whom he held in high regards. He would organize meetings for him as well as translate some of his work into French. After a period of several years, in 1928 he made a more permanent move to Paris to start a job at an electrical factory. In Paris he came across Paul Brunton’s book Conscious Immortality: Conversations with Sri Ramana Maharshi that started a burning desire to go to India.

His wish came true several years later when in 1935 he was offered a job to set up an engineering firm in Mysore, which he accepted. In his early years in India in the late 1930s he found Ramana Maharshi and spent time with the Bhagavan. As one of the regular devotees, many of his questions and the master’s response were recorded in Maharshi’s Gospel. Ramana said of Frydman “He belongs only here to India. Somehow he was born abroad, but has come again here.”

Concurrently he came into relationship with Mahatma Gandhi and was involved with his struggle to free India from British rule. It was during this time in 1938 that he asked the Raja of Aundh province to help Gandhi’s cause by freeing his control of seventy two village properties which the Raja agreed to. He then drew up a draft of declaration of independence which then was given to Gandhi. He in turn wrote the constitution of the state, giving full authority to the people of the state, a rare event in pre-independent India. An interesting side fact is that during his time with Gandhi Frydman worked on and improved the design of the cotton spinning wheels that became synonymous with Gandhi and his movement.

Frydman’s family perished in Poland during WWII and he never returned there after that.

At this juncture in his life he gave up on his job and worldly possessions. He took on the robe of a sannyasi under Sri Swami Ramdas who named him Bharatananda; a robe he later gave up as being meaningless while living the spirit of it to his death. From this time on, he did give up his salary to the needy around him. He had no room for symbols and spiritual materialism that did not reflect true ripeness; he found them to be shallow and counter productive. He regretted his inability to take further use of Ramana Maharshi’s teachings while the Bhagavan was alive. He wrote after Ramana Maharshi’s death, “Now He is still with us, but no longer so easily accessible. To find Him again we must overcome the very obstacles which prevented us from seeing Him as He was – and going with Him where he wanted to take us. It was Tamas and Rajas – fear and desire that stood in the way – the desire for the pleasure of the past and fear of austere responsibility of a higher state of being. It was the same old story – the threshold of maturity of mind and heart which most of refuse to cross.”

Maurice Frydman died in Bombay on March 9th of 1976 with Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj by his side. A beautiful event ends this incredible life. During his last days of life Frydman gets a visit by a professional nurse he does not know. The nurse had been visited in a dream by an old man in a loin cloth telling her to go and take care of Frydman. Frydman refuses to accept the nurse’s offer. As the nurse is leaving she walks past a picture of the old man that had visited her in her dream. Upon telling Frydman this, he accepts her offer and allows her to take care of him. The picture: it was Ramana Maharshi who had left his body over three decades prior.

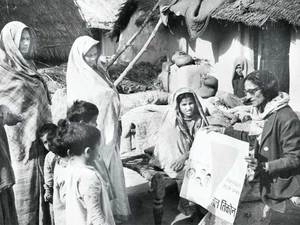

Frydman helped Wanda Dynowska, a Polish theosophist who came to India in the 1935 and visited Ramanasramam frequently, in 1944 to establish a Polish-Indian Library (Biblioteka Polsko-Indyjska). During the Second World War he helped with the transfer of Polish orphans from Siberia, displaced there by the Soviets after their annexation of Eastern Poland to Siberia in 1939-1941. They were moved from Siberia via Iran (with the Polish army of General Władysław Anders) mainly to India, Kenya and New Zealand. In 1960, after the 1959 Chinese take over of Tibet he helped Wanda Dynowska with Tibetan refugees in India.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Frydman

The Extraordinary Life of Maurice Frydman (Biographical Collection)

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Face_to_Face_with_Sri_Ramana_Maharshi.pdf

Urgyen Sangharakshita writes about his meeting with Maurice and his wife Hilla – They ran down the slope holding hands, laughing like happy children. The scene was the garden of The Residence, Gangtok, where they were staying as guests of Apa Pant, the political officer with whom I also sometimes stayed. It was my first sight of Maurice and Hilla. We soon became acquainted, and they invited me to visit them at their Bombay home the next time I was in the city. The time must have been the mid-1950s.

Read the full article https://www.sangharakshita.org/articles/some-bombay-friends

Sangharakshita, born Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood (1925 – 2018) was a British spiritual teacher and writer, and the founder of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, which in 2010 was renamed the Triratna Buddhist Community.

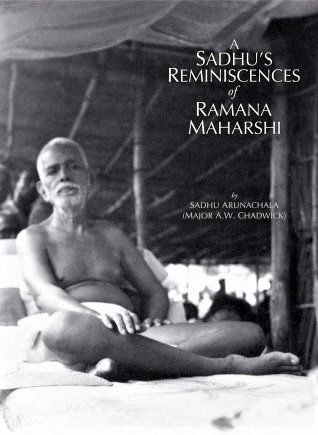

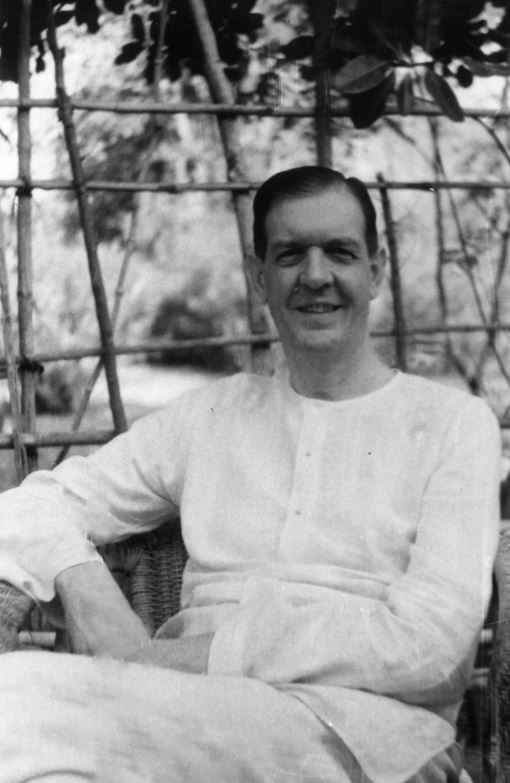

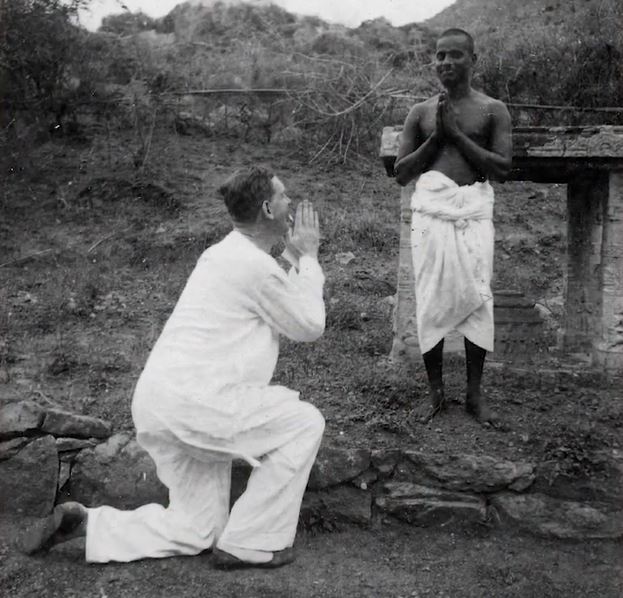

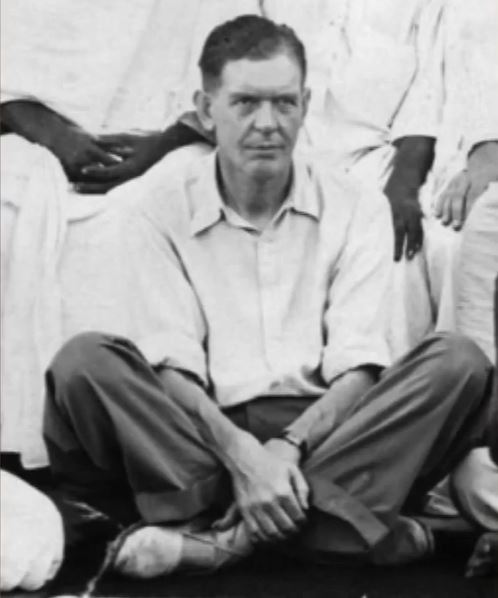

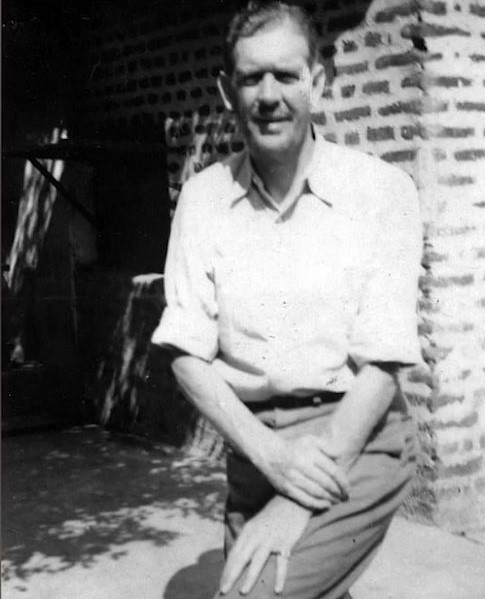

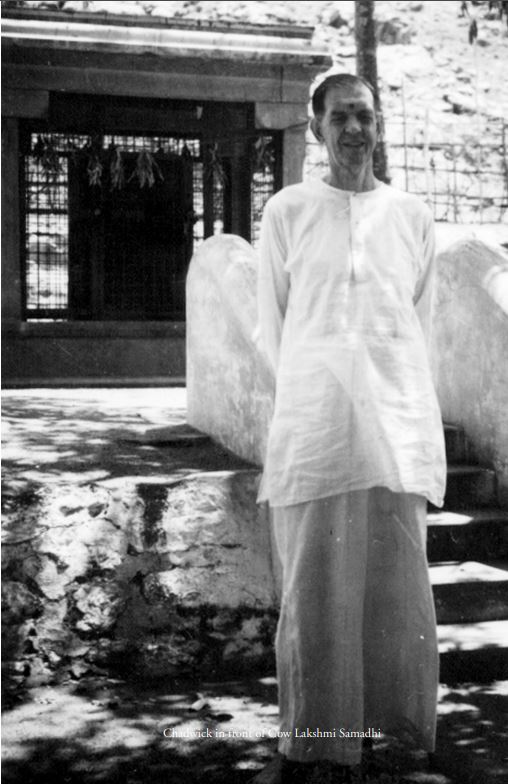

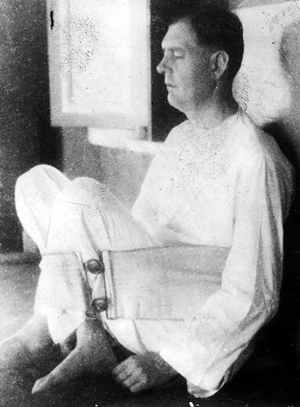

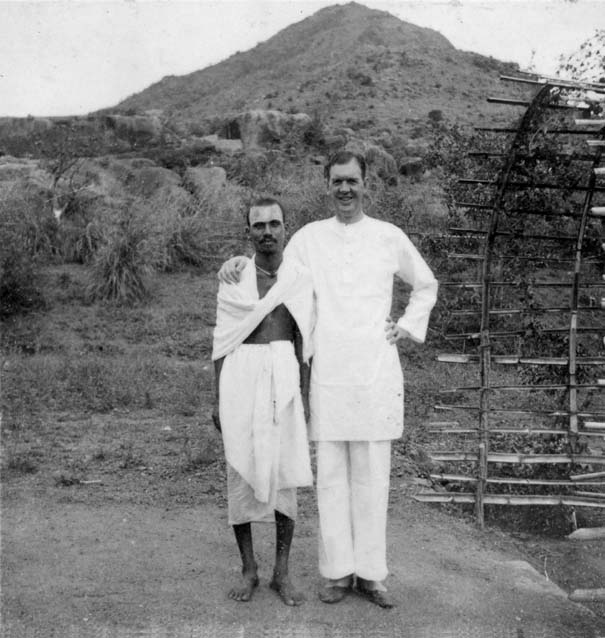

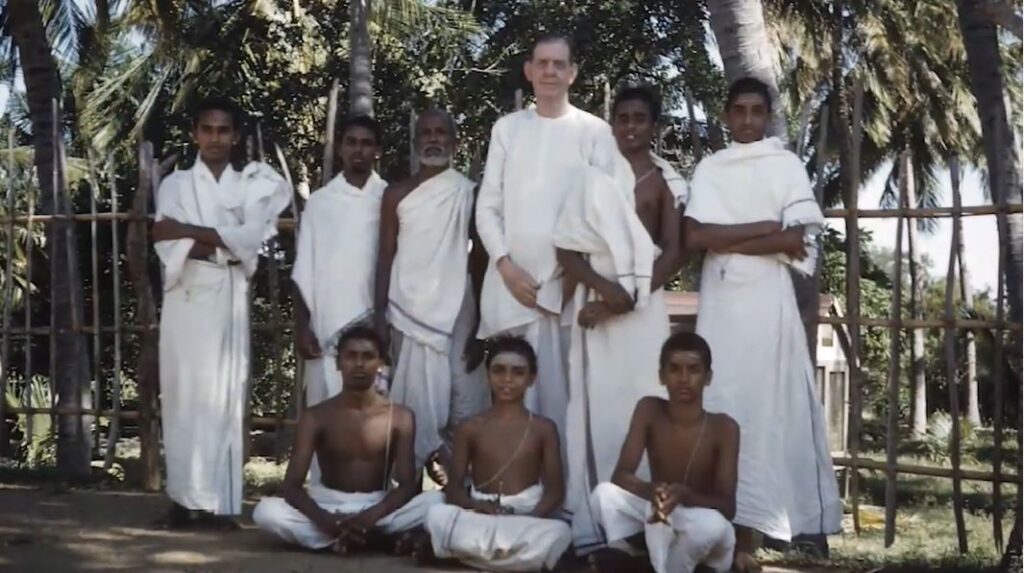

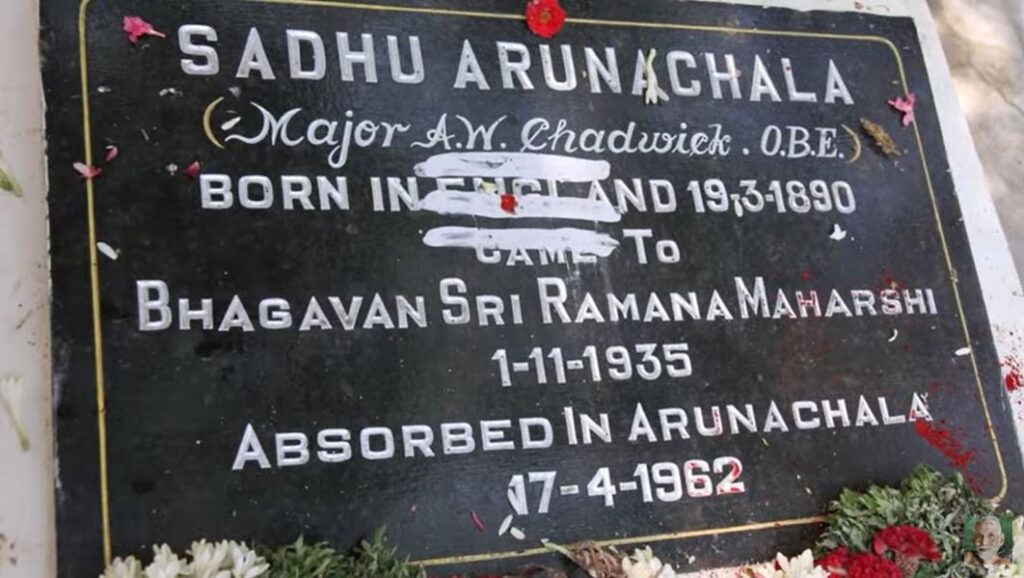

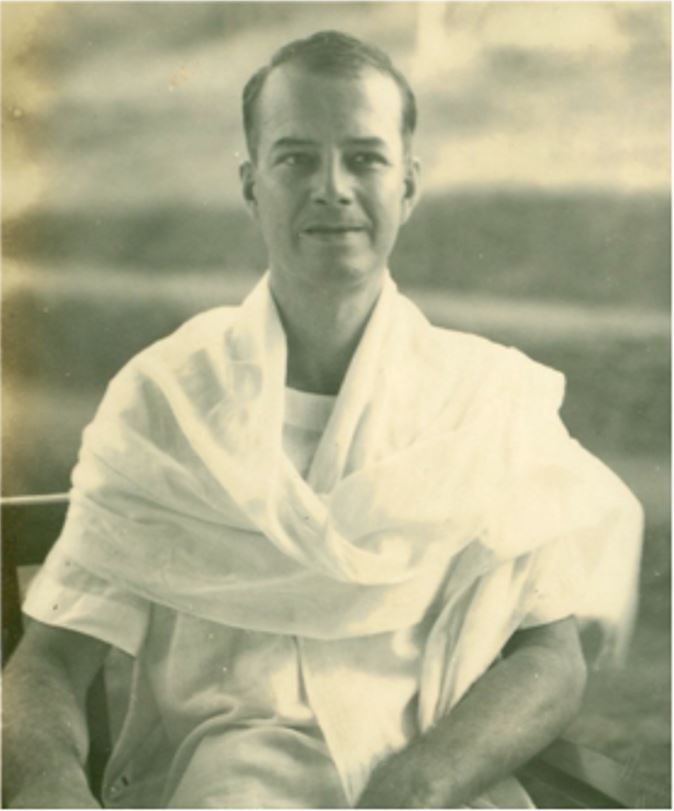

After reading A Search in Secret India Major Alan Wentworth Chadwick O.B.E. (19 March 1890 – 17 April 1962) who was in the British army serving in WW1 and afterwards living in South America, arrived in Sri Ramanasramam on November 1st 1935, and remained there for the rest of his life, becoming the first European devotee to live permanently at the ashram. He established himself at the heart of the ashram in a way no other Westerner could ever repeat. He was one of the few who had a relaxed relationship with Ramana. His cottage was like a foreign embassy in the heart of the ashram as he was able to mediate for so many who found at times the ways of the ashram difficult. He became Sadhu Arunachala and is buried in the ashram. He was instrumental in initiating the regular performance of Sri Chakra Puja in the Mathrubhuteswara Temple and helped start a Veda Patasala in the Ashram. He translated all the original works of Sri Ramana into English and wrote the book A Sadhu’s Reminiscences of Ramana Maharshi (1961).

Major Chadwick writes: In the early days of my stay (1935-36), I was living in a big room adjoining the Ashram storeroom. Here Bhagavan often used to visit me. On coming into my room unexpectedly he would tell me not to disturb myself but to go on with whatever I was occupied at the time. I would remain seated, carrying on with whatever I was doing at the time. I realize now that this was looked upon as terrible disrespect by the Indian devotees, but it had its reward. If one put oneself out for Bhagavan or appeared in any way disturbed he just would not come in future; he would disturb no body, so considerate was he. But if one carried on with what one was doing then he would himself take a seat and talk quite naturally without the formality, which usually surrounded him in the hall. I had no idea how lucky I was and how privileged, but certainly appreciated the visits. A Sadhu S Reminiscences of Ramana Maharshi, p.23.

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://selfdefinition.org/ramana/Ramana-Maharshi-Day-by-Day-with-Bhagavan.pdf

Download: https://archive.org/details/asadhusreminiscencesbychadwicka.w.sadhuarunachala_202004_466_K

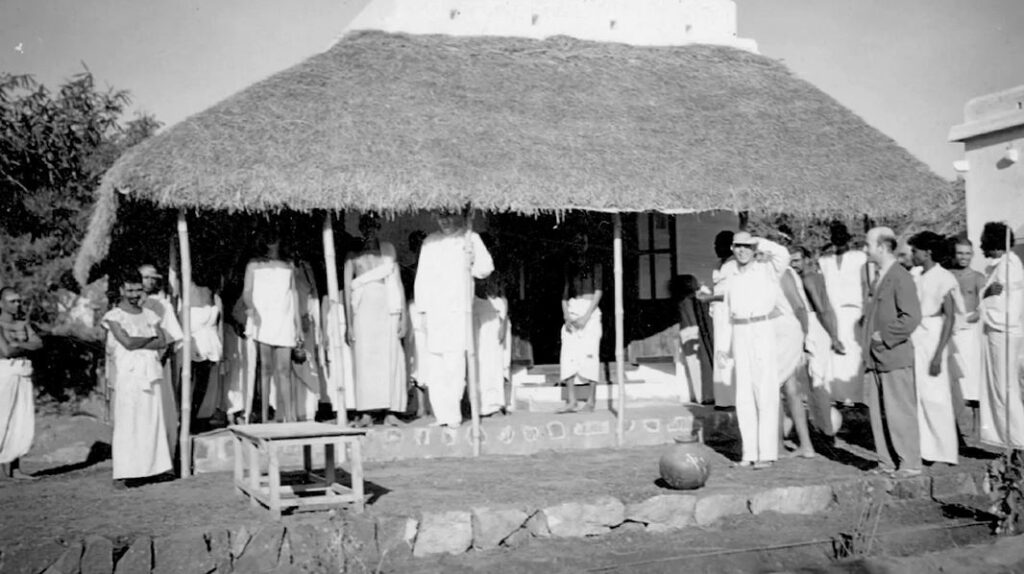

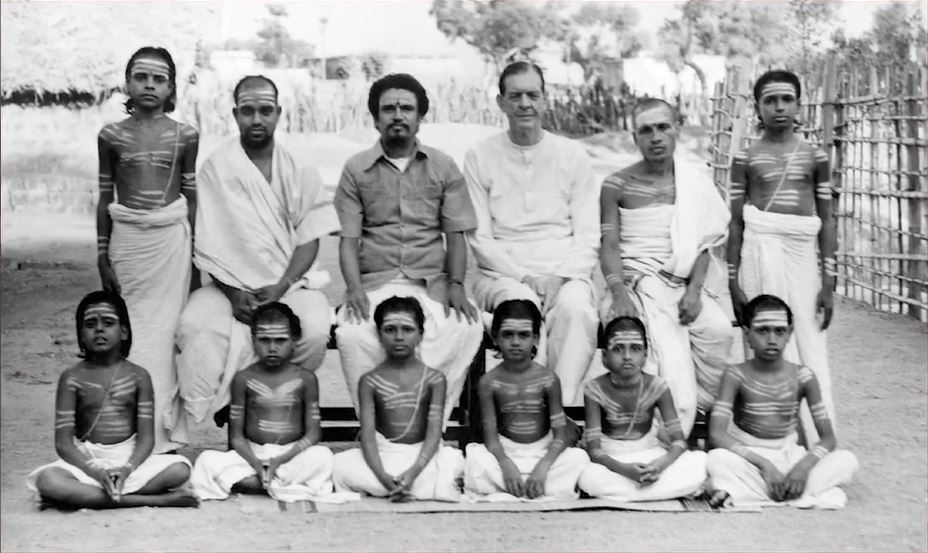

taught to chant the Vedas.

The Ashram Vedic School was established in 1934 for the regular instruction in the Krishna Yajur Veda with students performing daily recitation of the Vedas in the hall. Prior to this, pundits from town had come each day for morning and evening recitations and would chant before Bhagavan who, it is said, would sit bolt upright each time they began. Among the group from the school in town was a senior student, Sri Krishna Ghanapatigal, who was selected in the presence of Sri Bhagavan as the first Ashram Veda Patasala teacher, and who in time proved instrumental for the steady growth of the newly formed Ashram school. After Bhagavan’s Mahanirvana, the school closed temporarily for lack of funds and it seemed that the chanting of the Vedas, which had become such a regular part of Ashram life, might come to an end simply because there was no one to carry it on. In 1953 the Ashram Managing Committee authorised Major Chadwick to solicit funds to revive the school and to initiate the Sri Chakra puja in the Mother’s Shrine. Under Chadwick’s stewardship, funds were raised and, five days after the Sri Chakra puja was inaugurated in March, 1953, the Ashram school was reopened.

In the 1970s the school again suffered from lack of funds and students, and appeals were made for support. Finally thanks to Sri Vaidyanatha Ganapatigal of Mysore, the school was revitalised. In 1980, after 40 years of service, Sri Krishna Ganapatigal retired and was succeeded by Sri T.S. Ramaswamy Ghanapatigal. Today, under the guidance of Sri Sentilnatha Ghanapatigal, the school enjoys a vitality, enthusiasm and regular influx of students unknown since the Patasala’s inception nearly 80 years ago (2013) https://archive.arunachala.org/sri-ramanasramam/veda-patasala

VS Mani recalls his time with Major Chadwick. Excerpt from Sri Ramana Maharshi – JNANI : The Silent Sage of Arunachala.

Major Chadwick and The Razor’s Edge

From Tracing the Pilgrim Life of Ella Maillart Part II by Michael Highburger (The Mountain Path April 2019) – In the course of conversations with Ella on the veranda of his hut in Ramanasramam, Major Chadwick narrated the account of Somerset Maugham’s scandalous visit to Sri Ramanasramam in 1938:

“Somerset Maugham ran away from Pondicherry, he hated it so much. He came here with Mrs. Austin, had lunch in front of Olaf’s hut with beer and gin – what a horror! Chadwick sent everybody away to avoid a scandal. Then Somerset Maugham asked to lie down. Chadwick sent Grant Duff away from his room and (went to tell) Bhagavan that Somerset Maugham (was not in a position to) come to the Hall. So Bhagavan came (to Chadwick’s hut) and sat opposite Somerset Maugham for half an hour. At the end of it Maugham said: “Do I need to say something?” “No, silence is a good thing,” Bhagavan said. (Bhagavan then added:) “I ought to go back (to the Hall). They will be waiting for me.”

Maugham had not made a great showing and Chadwick was unhappy with him. But Maugham seems to have been awestruck by Chadwick. In a letter to her mother in Switzerland, Ella writes: “Chadwick had impressed Somerset Maugham because he looked so perfectly happy. Do you remember, I must have told you that I had lunch with Somerset Maugham at his daughter’s place just before he left for India; he was certain that Europe had run off the track somehow

and he wanted to see something of the ageless wisdom of India.

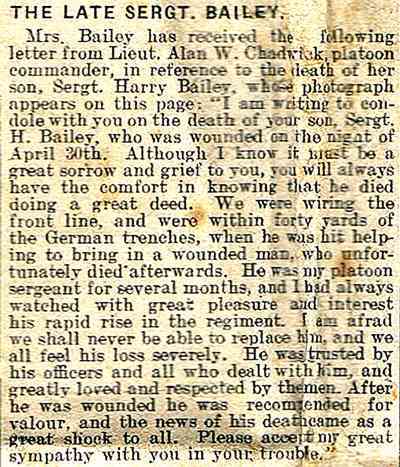

Neither Chadwick nor Ella realised that Maugham, despite having behaved inappropriately at the time, had in fact been deeply taken by his experience of Bhagavan. Indeed, when his bestseller was published in 1944, anyone who had ever visited Ramanasramam would have easily recognised the spiritual master Sri Ganesha as based on Bhagavan. Few, however, would have been able to identify Major Chadwick as the principal subject on whom Maugham’s iconic character Larry Darrell was modelled. Both Larry and Chadwick were from good families, both had been wounded in the First World War, both had lost a close friend in battle, and at the end of the war, both gave up promising careers in order to travel to India to seek the transcendental meaning of life.

Though unimpressive during his visit, Maugham had presciently diagnosed the spirit of the times and landed on the emerging archetype of twentieth-century Europe. His character matched not only the life of Major Chadwick but that of Guy Hague, Lewis Thompson, Paul Brunton, S.S. Cohen, Maurice Frydman, Ethyl Merston, Grant Duff and countless others who, like Ella, had come to live with Sri Ramana long before the appearance of The Razor’s Edge. Ironically, as Ella and Chadwick joked about Maugham on Chadwick’s veranda at Ramanasramam, Maugham was publicly validating their vocation and making them into unwitting heroes through the character of Larry.

Hans-Hasso Ludolf Martin von Veltheim-Ostrau in December 1935. From November 11, 1935 to April 19, 1936, Veltheim traveled to India where he also visited Swami Sivananda, whose business expansion and personality cult he later criticized. Through Annie Besant he became close to theosophy, especially to Jiddu Krishnamurti, who she temporarily postulated as a world saviour and who stayed in Ostrau for a week in 1931. Later encounters with him and other Indian gurus such as Ramana Maharshi influenced his spiritual development.

From Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi 23rd December, 1935. Talk 114. Baron Von Veltheim – Ostran, an East German Baron, asked, There should be harmony between knowledge of the Self and knowledge of the world. They must develop side by side. Is it right? Does Maharshi agree?

M.: Yes.

D.: Beyond the intellect and before wisdom dawns there will be pictures of the world passing before one’s consciousness. Is it so?

Sri Bhagavan pointed out the parallel passage in Dakshinamurti stotram to signify that the pictures are like reflections in a mirror; again from the Upanishad – as in the mirror, so in the world of manes, as in the water, so in the world of Gandharvas; as shadow and sunlight in Brahma Loka.

D.: There is spiritual awakening since 1930 all the world over? Does Maharshi agree?

Maharshi said: “The development is according to your sight.”

The Baron again asked if Maharshi would induce a spiritual trance and give him a message – which is unspoken but still understandable.

No answer was made.

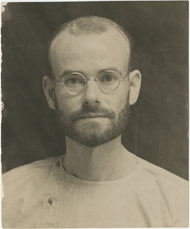

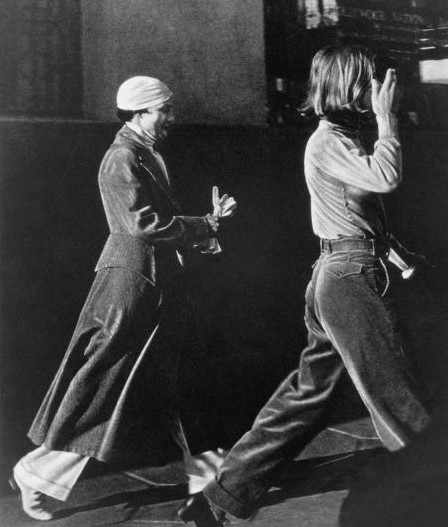

English Poet Lewis Thompson arrives in the ashram in approximately 1935 and stayed for 7 years. He is one of the greatest, and least known, mystical writers of the twentieth century. Born in London in 1909, he became a wanderer in his early twenties. He left England and never returned. Travelling through France and Germany, he was haunted by Rimbaud’s vision and by visions of great cities. The London and Paris of Cocteau, Picasso, and Diaghilev in the 1920s made an unforgettable impression on him. At one time he thought of becoming a pianist and was a sensitive interpreter of Bach and Debussy throughout his life.

Thompson lived in India for the last sixteen years of his life and was, for several years the librarian at the Rajghat school in Benares. He lived with Hindu simplicity, indifferent to the British Raj and its lifestyle, and devoted himself completely to an exhilarating, agonising, and profound spiritual search that took him to ashrams all over India. Andrew Harvey writes in 1998, “For a while he had a guru in South India, Sri Atmananda Krishna Menon, but a terrible quarrel separated them; later he was to write very savage things about the guru system.”

From Death Must Die – Lewis Thompson was closely associated for a number of years with Sri Krishna Menon, a highly respected South Indian master of Advaita Vedanta – the ancient Upanishadic philosophy of nonduality, as defined particularly by Adi Shankaracharya (788 – 820)? It seems that Thompson, in the outspokenness of his passionate philosophical disputations with his teacher, had overstepped a certain line of fundamental etiquette and respect in his relationship with him. This rift was exacerbated by the jealousy of some of the other followers and ultimately the Guru asked him to leave.

Thompson neglected his health and died suddenly in Benares, four years after his arrival there, of sunstroke in 1949, at the age of forty, before he had time to prepare his recently completed work for publication. A collection of his aphorisms, Mirror to the Light, which was edited and published in 1948; a great majority of his unique poetry remains unpublished.

In his brief lifetime, he accomplished what almost no other writer of his or any other time has been able to do: to gather the disparate elements of the chaotic literary inheritance of the West and to somehow seamlessly integrate them with the deepest and most purifying spiritual realities of the East.

Thompson arrived on the ashram in approximately 1935 and stayed for 7 years. His life and work stand as a radically progressive regeneration of what it means to be an artist – in his case a poet – by refining the literary traditions of the West into a deeply immersed practice and understanding of the spiritual traditions of the East. He was in every sense the consummate writer. He was also a genuine sadhu, a wandering spiritual renunciate of the first order.

When Thompson arrived at the Rajghat school in Benares, Austrian Blanca Schlamm (Atmananda), as the only other foreigner, was asked to look after him. The newcomer was seriously in search of truth. When he had not found spiritual guidance in Europe, he came to Ceylon, thereafter he spent seven years with Ramana Maharshi in Tiruvannamalai. Otherwise, too, he had met many great spiritual personalities of that time, even those who were not easily accessible and known only to insiders.

Atmananda stressed that he had a sharp intellect, was highly analytical and radically pushed aside everything that he felt was not genuine. When Atmananda talked about him it was sensed that she liked him.

Thompson had come to Benares because of Anandamayi Ma. She was staying in Sarnath, some distance from Benares, where Buddha gave his first sermon after enlightenment. Thompson wanted to be back in the evening and did not show up for three days. He had not taken any change of clothes and in the school had been a case of cholera. Atmananda concluded that he must be sick. She bought medicine and went to Sarnath. There she found Thompson hale and hearty and completely enraptured by Anandamayi Ma. “She surpasses my highest expectations. It is incredible, how profound her answers are” he gushed.

Atmananda gave her diaries to Ram Alexander, who had come to India as a young man in the early 1970s. The diaries are now published as Death Must Die. Anandamayi Ma offered Ram the chance to live in her ashram in Kankhal, a privilege rarely granted to a foreigner. He stayed in Ma’s ashram for about 10 years. Thereafter, he married and settled in Assisi, Italy.

Atmananda felt that Ram was Lewis Thompson reborn. That was the reason why she wanted him to have her diaries, and publish them if he thought they would be helpful to others. Ram did not disappoint her, and got them published under the title, Death Must Die. His foreword shows literary flair, but unlike Thompson, in this life he does not live in penury.

Atmananda’s diaries have by now become a sort of underground bestseller. The book is often see with foreigners. It fascinates, because it is very authentic. Source: Sri Ramanasramam, Andrew Harvey, and Maria Wirth.

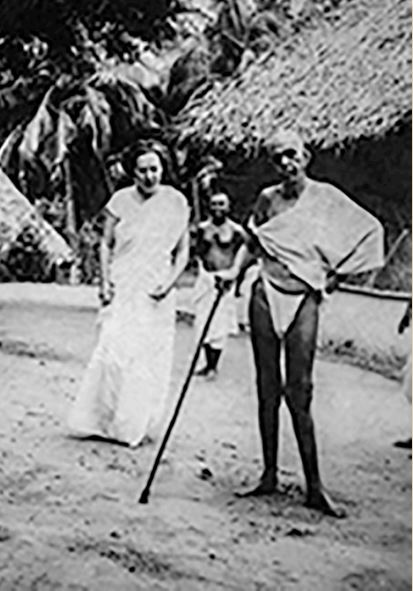

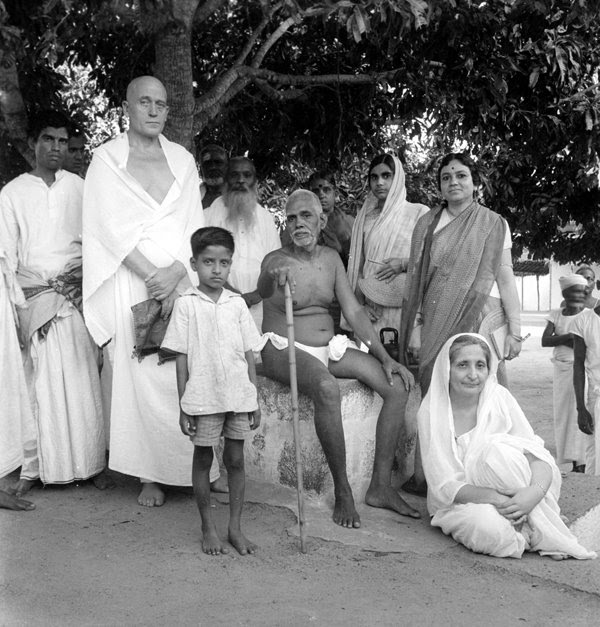

The picture is taken from the book ‘Ti-Puss by Ella Maillart.

Do as the cat! During her stay in South India (1939 – 1945), Ella Maillart was taught by two masters of wisdom, Ramana Maharishi and Atmananda (Krishna Menon). Far removed from a war-torn Europe, she leads a quasi-ascetic life and examines herself in her mirror: A tiger cat whom she baptizes ‘Ti-Puss. The remarkable animal reveals to the traveller that there is audacity in wanting to live life in the present, in searching for the meaning of existence in one’s everyday pursuits and circumstances. It is ‘Ti-Puss who encourages the author to apply the spiritual lessons to the material world. “Because a cat,” says Ella Maillart, “knows how to live the fullness of the present moment.” Written in English. W. Heinemann, London, 1951.

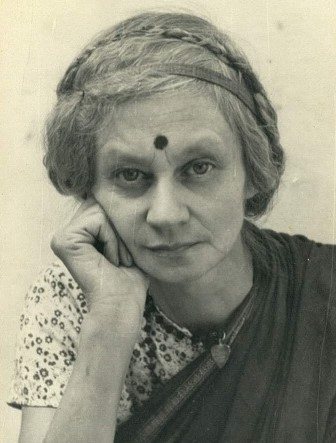

Polish writer Wanda Dynowska (Uma Devi) (Tenzin Chordon) lived in India from 1935 until her death in Mysore in 1971, often visited the ashram.

Wanda Dynowska came to India in 1935 on a soul-searching mission. Born to Catholic parents of Polish nobility in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1888, Wanda was drawn to the Bhagavad Gita, the Koran and other spiritual books at a young age. This drew her to Theosophy and particularly to Annie Besant.

While in India she stayed at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar and made frequent trips to Ramana Maharshi’s ashram.

She was a bridge between Poland and India exchanging the richness of their cultures with publications and translations of over 100 books, including the Bhagavad Gita, the teachings of Ramana Maharishi, which attracted many Poles to come to the ashram.

She became a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi who christened her with an Indian name of “Uma Devi.” She raised resources for Polish refugees through the local Maharajas, and set up schools for them imparting Montessori education.

In 1944, together with another Polish visitor to Ramanasramam, Maurice Frydman, she founded the Indian-Polish Library in Madras, which became for more than thirty years a major editorial body for Polish translations of main Hindu religious texts as well as for contemporary Indian poetry and literature.

She was a spiritual seeker donning many hats. She went to north India to study Kashmir Saivism, with Swami Lakshmanjoo in the Ishwar Ashram, a distinctly variant school from that of Tamil Shaivism.

Her meeting with the the Dalai Lama, in 1956, was a turning point in her life, and drew her to a new Path. The Dalai Lama rechristened Uma Devi as Tenzin Chordon after she started to embrace Buddhism.

From 1960, she with the help of Maurice Frydman started helping Tibetan refugees in India. Living in their main centre in Dharmasala, Dynowska organised schools, education, and social infrastructure there. Additionally, she published Polish translations of Buddhist texts. She later settled down in the town of Bylakuppe near Mysore, the largest settlement of Tibetan refugees. The settlement is larger than that of Dharamshala. When her end came in 1971, she requested a Catholic burial, and her tombstone is a glaring memory of her unsung epitaph:

“Here lies a Universal Soul – a Polish Theosophist – Born a Catholic, embraced Hinduism and settled for a service in practical Buddhist altruism. She left behind a footprint which was deeply etched in the sands of time”

This East European Yogi was indeed an epitome of Light and Compassion. She opened the doors of Inner Light in both India and her native Poland.

Face to Face with Sri Ramana Maharshi Compiled and Edited by Professor Laxmi Narain.

https://www.stillnessspeaks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Face_to_Face_with_Sri_Ramana_Maharshi.pdf

American Dr Henry Hand in 1936,

From Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi 2nd March, 1936. Talk 174. Dr. Hand, the American gentleman, asked: Are there two methods for finding the source of the ego?

M.: There are no two sources and no two methods. There is only one source and only one method.

D.: What is the difference between meditation and enquiry into the Self?

M.: Meditation is possible only if the ego be kept up. There is the ego and the object meditated upon. The method is indirect. Whereas the Self is only one. Seeking the ego, i.e., its source, ego disappears. What is left over is the Self. This method is the direct one.

D.: Then what am I to do?

M.: To hold on to the Self.

D.: How?

M.: Even now you are the Self. But you are confounding this consciousness (or ego) with the absolute consciousness. This false identification is due to ignorance. Ignorance disappears along with the ego. Killing the ego is the only thing to accomplish. Realisation is already there. No attempt is needed to attain realisation. For it is nothing external, nothing new. It is always and everywhere here and now too.

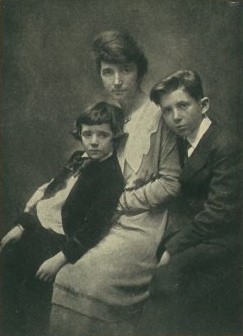

American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger visited the ashram in January 1936.

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879 – September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term “birth control,” opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, and established organizations that evolved into the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Sanger and How Martyn left Bombay on December 25, 1935, to attend the AIWC meeting in Trivandrum on December 28, “the famous day for which I came to India.” The opening ceremony was held at the New Hall, decorated with “a ceiling of white linen stretched beneath the roof, from which hung ropes and lanterns of white jasmine and crimson roses.” Sanger greeted the AIWC on behalf of the international birth control movement, wishing the women of India “success in their efforts to establish political, social, economic and biological rights for the joyful health of mothers in the new world of tomorrow.” After the AIWC, Sanger spent a week in Madras, giving speeches and attending meetings, then took two days to visit Paul Brunton, whose book on Indian mysticism, A Search in Secret India (London, 1934), had intrigued her.

She arrived January 10, 1936.

From The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 4: Round the World for Birth by Margaret Sanger;

About nine am P.B. called on his bicycle & I in a “tonga” & he on his cycle went to see Maharshi or Sri Ramana Maharshi or the Sage of Arunachala the one time Hermit of the Hill of the Holy Beacon & one of the last of Hindustan’s race of noble Rishees.

As we trotted along behind the horse in the tonga through a thickly settled village or town we passed the Pogoda Temple & always the Beacon Hill loomed up at every turn. The Secty was in the tonga with met & as we stopped at the market for a few plantins (bananas) as a gift for the Maharshi we could see the same colouring & hear the constant chattering of men women & babies, while always far & near is the rumbling of the bullock carts & the shrieking “[hay?]” of the driver shouting to people to get out of the way. At last we got to the ashram at the foot of the hill which is according to ancient lore the heart centre of the God Shiva a holy place & the spiritual pivot of the world. As we alighted, the Secty took the plantins in his hands but no sooner had he turned to help me out of the tonga than a temple monkey leapt from a near by tree, grabbed two bananas & as quick as a flash had the skins off & gobbled them down & with no concern whatever of his conduct looked around for another “grab.”

The ashram at last, shoes & sandals left outside & the Secty went ahead in case the Maharshi was elert to my arrival. He was, he was reading the morning paper but looked up quickly & asked who it was I heard the Secty say Mrs Sanger & the Maharshi repeated Mrs Margaret Sanger? The Secty said Yes I bowed & took my seat on the floor near the door way, crossed my legs & feet under my dress & looked about me to get & feel & sense the atmosphere. The Maharshi went on reading his paper. There was a book shelf & table revolving kind near his couch. He was seated cross legged on a couch about 1 1/2 feet from the floor.

It was covered with a silk cover pillows behind him & a leopard skin thrown over the foot of the couch. He sat reading, evidentially the news of his birthday celebration. Over two thousand people had assembled the day before Jan 9. to celebrate his 56th birthday at the [space left blank] of the moon.

The Maharshi’s face was one of character, peace & suffering transmuted into joy.

He has battled with the Self & subdued it. He has thought through dogmas & cults & brought himself through to Principle, upon which all his answers are based to questions his devotees put to him. He sits unconcerned at the prostration of the Self of hundreds of men, women & children who bow & fall full length, spread hands above their heads on the floor before him. Head touches the floor three times. They arise & take a place in the ashram to sit & meditate as long as they like. Only when children, babies, are made to lie flat before him, does he smile, sceptically I thot. Also when a small boy about three or four came in alone & said part of a prayer in Tamlino but forgot the rest did the Maharshi look amused in understanding, but for the rest he was unconcerned. A small char coal fire & incense burned beside him & attendants saw to it that it burned throughout the day. At first it was nicely quiet, then some women began to sing. These songs are Sacred hymns & are sung in a pitched tone much through the nose & head doubtless good for the pineal gland & may exercise it. The men chant aloud & then someone plays a stringed instrument, but the Maharshi pays no attention to it all. His eyes are open, his body relaxed, his fan held straight there he sits apart from it all. The hundred people in the ashram are left over from the birthday celebration. So there is more confusion & chatter than usual. I got into a silence full of lightness for a while, but the women’s voices in Song brought me out of it.

We sat until noon when P.B. took me to his hut for lunch. He cooked it himself a very nice one of Cauliflower, millet curry beans, potatoes, pineapple oranges & grated cocoanut. We went back to the ashram about three thirty & I asked two questions “Does knowledge cause morality or immorality” “are we made immoral by outside factors or forces.”

Also “Is continence the only means allowed married people to control the size of the family.”

There was much stir at the first question & as the questions had to be interpreted the answer came back “What is birth?” “When we find the cause of birth we can control it.”

I insisted that I had said nothing about control of birth at all, but morality. So then the answer was that It was not the question of morals at all but of desire. This seemed to please all present, including myself. Then the next question was replied to by “of course” meaning that Continence was the only means allowed or morally sanctioned. I came back to expostulate & tried to bring the fact of mothers & infants loss in death & the waste of life in trying to impose this method on the masses. Much talk & silence. The interpreter seemed to impose his own ideas and we could do nothing but take them. Later on when we were assembled in the yard several men alive & alert came & told me he had not correctly interpreted the Maharshi’s answers. So I’ll try again. We all sat around on the floor in the dining hall & had our supper on a banana leaf as a plate. This time we the Westerners had spoons. This leaf is folded up & each one clears his own place neatly & the leaf is thrown in the garbage pile hands are washed & back I came in a tonga drawn by a white bullock. The moon was full & the drive back was full of colour & peace, but not quiet as the driver shouted himself hoarse at other drivers who all go higgly piggly this way & that through the streets. The parade of people with torches carrying goods to the temple was on!

From Margaret Sanger An Autobiography (1938) she writes;

I had determined to take advantage of Paul Brunton’s offer and visit Sri Ramana Maharshi, the sage of Arunachala, the quondam Hermit of the Hill of the Holy Beacon, and one of the last of Hindustan’s race of noble rishis. Consequently, one evening a little after six, the train came around the bend and I beheld the sacred mountain, according to ancient lore the heart centre of the god Siva and, therefore, of the world. I knew it must be the mountain even without being told so. The sun had just set, and the afterglow gave a lovely, serene effect.

The Maharshi’s secretary, Shastri, met me, and we walked through the gathering dusk to the guest house about a half-mile away, a simple room with veranda in front. Paul Brunton had not been able to come because it was the Maharshi’s birthday and thousands of devotees had to be fed. Shastri was very loquacious, and wanted me to realize that the apparent success I was having was only with the educated classes; the masses knew nothing of it. This, I said, would come in time.

After breakfast I looked out at the great tamarind trees on the lawn, up and down which monkeys ran. Often twenty, from babies up to grandparents, were in sight all at once. The windows had to be barricaded at night to shut them out of your room; they especially loved bananas but did not disdain cakes of soap.

While I was watching them scamper about, Paul Brunton pedalled up on a bicycle accompanied by a tonga for me. The driver cried out continually, “Haiee! Haiee!” which seemed to mean both for people to get out of the road and for the white bullock to move faster; he shouted himself hoarse at other drivers, who went higgledy-piggledy this way and that through the streets. We stopped at the market for a few bananas as a gift for the Maharshi; he preferred food to flowers, because this he could give away. Then we trotted along through the thickly settled village, always hearing far and near the rumbling of the carts and the screeching of the drivers, “Haiee! Haiee!”

At last we reached the ashram at the bottom of the Hill. Shastri gathered up the bananas in his hands, but no sooner had he turned to help me out of the tonga than a temple monkey leaped from a neighbouring tree, snatched two of them, and as quick as a flash had the skins off and had gobbled them down with no concern whatsoever as to the ethics of his conduct. Instead, he peered around for another grab.

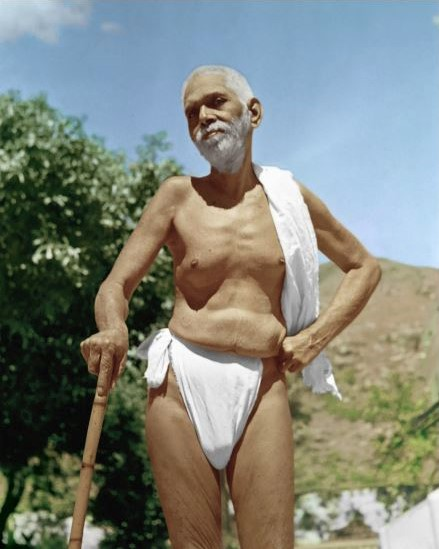

Shoes and sandals were left outside the ashram, and Shastri went ahead to announce my arrival. I bowed in the entrance and took my place on the floor just within, crossed my legs under my skirt, and looked about me to feel and sense the atmosphere. The Maharshi, naked save for a loin cloth, was sitting cross-legged on a silk-covered couch, pillows behind him and a leopard skin thrown over the foot. A small charcoal fire and incense, which attendants kept burning all day, sweetened and made heavy the air. The Maharshi’s luminous eyes were fixed in a trance, although sometimes his fan lifted a bit and his stare widened.

At first it was nicely quiet; then some women began to sing in a high-pitched tone, much through the nose and head, doubtless good for the pineal gland, once supposed to be the seat of the soul. The men chanted aloud and someone played a stringed instrument.

Towards eleven the Maharshi shared his gifts among those who sat in reflection, and shortly afterwards a man from Kashmir, six feet tall and massively built, entered, prostrated himself as hundreds had done already, falling full length, hands outspread above him on the floor, touching his brow three times. As he rose again his whole body shook, tears streamed down his cheeks. To see women cry from excess of emotion did not bother me, but when a man of such a type as this, in no sense a weakling, went into paroxysms of ecstasy, it was beyond my comprehension. With no critical intent, but curious to know why he had been so moved, we asked what had happened to him.

“When I came into the Maharshi’s presence it was as though electricity had passed through my body. I felt when I bowed I would be calmed, yet when I looked into those eyes, he was like a flame.”

This pilgrim had come with financial problems, illness in his family, and other troubles, but two or three hours of contemplation had wiped them out; he knew they were insignificant and trivial in contrast to his regeneration. In faith, the people in the ashram were comparable to those who cast away their crutches at some miracle-working shrine, except that they had come for inner illumination rather than healing for bodily ailments. They visited the Maharshi to receive the radiance of his soul, just as we sought the sun to be warmed.

Only when children or babies were made to prostrate themselves did the Maharshi smile, somewhat sceptically it seemed to me. He appeared amused when a boy of three or four began a prayer in Tamil but forgot the rest. Otherwise he remained apart from it all. He was gradually withdrawing himself and letting go material things. He wanted spiritually to fade away, leaving the shell behind.

The second day the Maharshi slept; nothing save an occasional singer broke into the hush, or a monkey had the temerity to dash in and seize an orange.

For the third day I attended the ashram. Now the meditation was like a linking up of mind and emotion, where even breathing was stilled. I could understand why the yogis went into the silence. Even the noises next door, the clatter of dishes, sounded remote and very far away. It was a state of consciousness rather like that which precedes sleep.

I regretted that I did not feel the Maharshi’s power. His utter indifference – sitting all day in a semi-trance, engaging in no activity – seemed to me a waste. Nevertheless, I was most grateful to Paul Brunton for the experience, and understood the Indians better thereafter. They saw within and beyond the external appearance; this was at the very basis of their character, akin to the sensitivity of the grapevine telegraph. All people in the Orient spoke of it. Something happened to you or to me and before you could get to another place by the fastest conveyance it was known. Perhaps it was a primitive function of mind, this form of thought transference, but it existed there.

Margaret Sanger (1879 – 1966) – Through her work as a nurse in New York’s Lower East Side in 1912, she worked hard to improve birth control practice to prevent unwanted pregnancies. This groundbreaking shift in attitude led to the foundation of the American Birth Control League. Sanger is credited with playing a leading role in the acceptance of contraception.

Women and the New Race by Margaret Sanger (1920).