2018 Interview and editing: Ginta Gaivenyte

Photos: Sarune Cepulyte and Ginta Gaivenyte

I bought a new airplane ticket and when the day came, I sent my belongings back to the monastery and prepared to take a leave the next day. But that night as I set about to pack my small bag, something prevented me from doing so. I was unable to put my belongings in the bag. I thought to myself, “This is very strange. I have never missed a flight in my life till now and here I am going to miss two flights in a row?” I went into the Ashram Hall and met an elderly friend and told her that I was supposed to leave the next day but that I could not pack my bag. She said, “Oh, don’t worry, just go home and go to bed and see what tomorrow brings.”. The next morning the taxi came at the appointed hour, but I did not get into it.

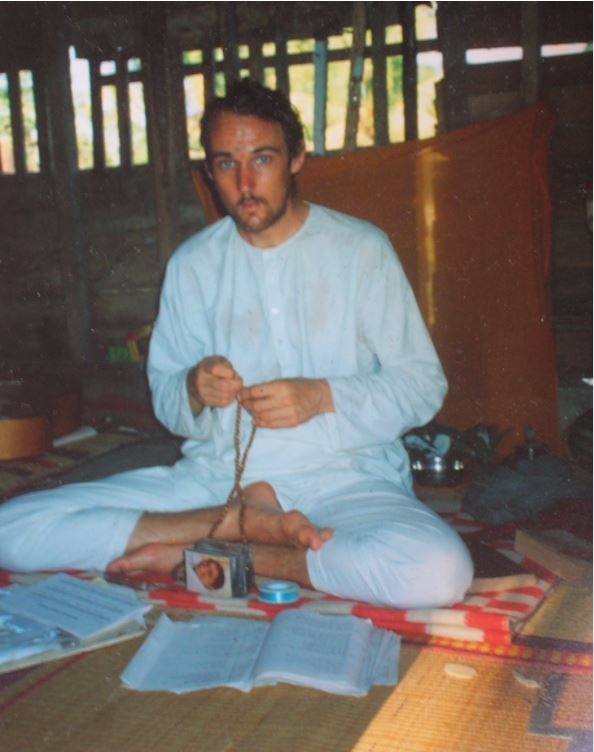

That day in Tiruvannamalai was hot. We were sitting on the stairs near the Ramanashram dining hall. „Are you still praying?“ – the question I gave to brother Michael was not accidental. Not rarely I heard westerners (especially those who call themselves the followers of Ramana Maharshi) speaking that there is no need to pray, it is better to ask yourself „Who am I?“ So for me it seemed logical that a monk from America who abandoned the monastery and is living now in Sri Ramanashram probably does not call God anymore.

A monk from America smiles and answers my question immediately. „Yes, I pray“, – he says without any sign of doubt. Then Michael Highburger explains that we, westerners, often see the conflict where indians do not see any conflict. If we believe in God, then we do not look for the True Self, or if we look for the True Self, we abandon praying and rituals. And India is full of paradoxes.

The life of brother Michael seems also full of paradoxes. Benedictine monk comes to India? And he does not feel like he betrayed christianity? He even believes that he can follow Jesus better in India? Can it really be like this?

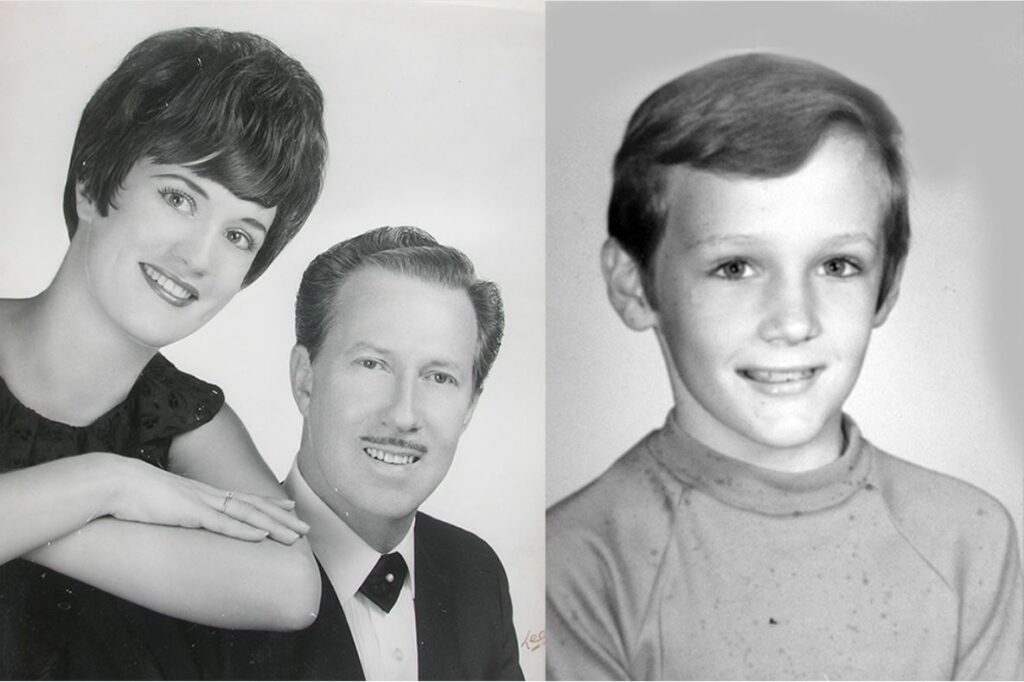

When I was nine years old we went on a family vacation to a famous water falls. We were swimming and I ended up right below the giant falls which pushed me under the water. I was still small and though a good swimmer, could not overcome the force of the waterfall which kept me under the water. Panic set in and I thought everything was over. Just then a big hand grabbed hold of me and pulled me up with great force. It was my father who evidently had been watching and knew I was in trouble and came to the rescue just in time. The memory stuck with me, about the fragility of life and the proximity with death. As it would turn out, just eight years later my mother drowned in a boating accident. I was then confronted face on with death and this was the beginning of my spiritual life.

– You studied philosophy. Did you hope to find the answers to your existential questions?

– I had taken up the study of philosophy imagining that by so doing I might find some answers to my many existential questions. But after ten years of study, I was more confused than ever.

I was doing field research for graduate work in linguistic anthropology in Guatemala. I was living in an abandoned convent, studying Spanish and doing field work. Because I had always had some form of physical exercise as part of my daily routine at University, I was missing that in Guatemala. But it so happened that there was a Colombian fellow teaching yoga there in the convent compound. I had never done yoga but thought it was better than nothing, so I joined the class. All went well but I was troubled that I could not follow the last exercise each day where we were instructed to lay on our backs, follow our breath and still the thoughts in the mind. It was this last instruction that I had trouble with. My mind was always racing about and only in this exercise did I discover how unruly it was. The struggle to calm my ungovernable thought processes over the next four or five days that led to what I later learned is called a conversion experience.

– What happened? Can you share with us your experience?

– I found myself in utter and complete rapture at the beauty of the world around me. Every sight and sound had a completeness and fullness that I had never seen before. I was amazed that I had never seen how beautiful ordinary experience could be. I understood that what the poets and saints had written about was not hyperbole but that they were speaking from direct experience.

Over the coming weeks I began to understand that the life I was living was a mistake and could never bring any lasting fulfillment. I began to understand that there was a God and that He/She was the root and ground of everything, was in everything, moment by moment, including my own breath and beating heart. I had no language for describing what I was experiencing, having been for all my college years a thoroughgoing rationalist who viewed with suspicion words like ‘spirituality’ or ‘mysticism’. But now I had to acknowledge my arrogance and blindness, and I saw that my former view of the world based in science and reason was an illusion.

I found myself in such wonder at my experience that I could hardly let myself go to sleep at night. I could hardly wait for morning to come. So I would wake and 1.30 or 2 am and be disappointed that everyone was still asleep and that I could not get up yet.

One morning about two weeks after this experience I remember walking about in the street where I was living and encountering a small pile of garbage and was beside myself at the beauty in the colors of the items in the rubbish heap. I mused to myself: What is happening to me that I can see a pile of garbage as one of the most beautiful things I have ever experienced? All my views about what the world was made of–and I had many views–all seemed to pale in comparison with this direct experience. All my theories and opinions seemed so vain and empty and unreal by comparison with plain seeing. I knew that my life to that point had been an illusion and I knew my academic career was over, that I could never be sustained by vain intellectual pursuits any longer.

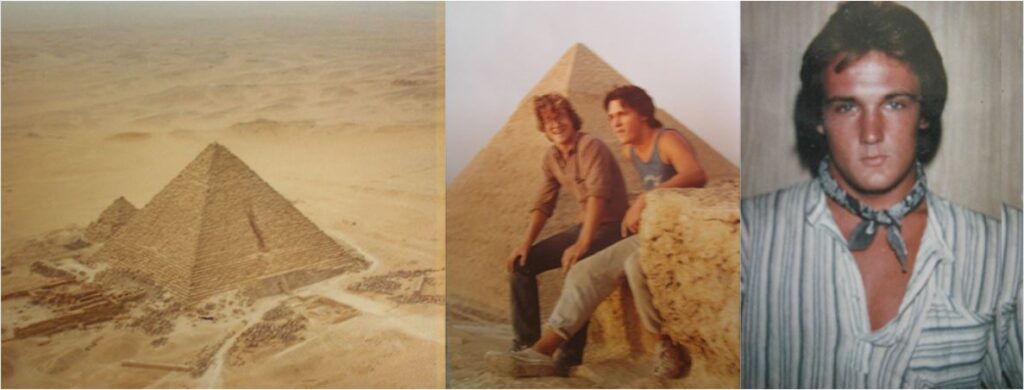

I made up my mind to return to the US, leave university, give away my business and go on pilgrimage. I didn’t really know what pilgrimage was, but since this all started in Guatemala, I decided to return there and make my way down to South America. Since the first beginnings took shape in the context of yoga, I began reading books on yoga and spiritual India, so decided that my 5-year pilgrimage should culminate in India. This first pilgrimage lasted only two years instead of five as my family had need of me and it seemed that I should go and help them. But other pilgrimages followed. It has been nearly 30 years since those months in Guatemala and I never once regretted the decisions made in the aftermath of that first experience.

While on pilgrimage in Central and South America, I took up meditation practice which I discovered through my research, and learned that others who had had similar experiences to my own were often practicing meditation. In Costa Rica I came across Phillip Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen in which were eight personal testimonies of people who experienced what I had experienced and so when years later I was back in the US, I contacted Kapleau’s center, the Rochester Zen Center, and went for numerous retreats there. In discovering Zen for the first time, I learned that it describes itself as a ‘tradition outside the scriptures, beyond words and letters’. This resonated with me deeply since I had been so immersed in the written word in my academic career, but only began to live truly when discovering the wonder of direct experience and seeing with fullness of the senses and awareness, ‘reading’, so to say, the world around one. It was the acting teacher in Rochester who encouraged me to develop that and to go on a reading fast, which I did for the next seven years. Only after joining a Benedictine house in California (New Camadloi Hermitage) my mentor, Fr Bruno Barnhardt, recommended that I take up reading again.

– How comes you entered catholic monastery? You could choose a zen monastery instead. Have you prayed in a christian way during your wanderings?

– I was just trying to find my way, like a fly trapped in a glass bottle that flies hither and tither until he comes free. So after the conversion experience, I decided to make myself open to every possibility and not rule out anything based on previous prejudices. The upshot of all that experimentation with other religious traditions was being led me to the Church and Christian life. It’s not that I was praying so much in a strictly Christian way but it was also not not a Christian way of praying.

Mother Teresa said when a journalist asked her about what she says to God when she prays. She said, “I don’t say anything I just listen”. Then the journalist asked her, “What does God say to you when you pray?” She said, “He doesn’t say anything, he just listens.” This is a beautiful description of contemplative prayer, which in the final analysis is neither Christian nor non-Christian, after all silence is the purview of prayer in all traditions.

This is not to say that my prayer life does not include formal intercessory prayer making use of tradition Catholic formulas which I rely on heavily. Christ is the one I cry out to when in need, and the Jesus prayer is an ongoing part of my interior life. ‘Just listening’ is not at odds with word-prayer but are complimentary and go hand in hand. But the endeavour to learn contemplative pray can be augmented by traditions that specialise in that form of prayer and adapted to the Christian setting.

– Can you tell more about your life in Benedictine monastery? For example, I would be glad to know how you felt the impact of Gregorian chanting.

– One of the great things about Benedictine life is the daily office, singing the psalms publicly four times per day. It is said that this is why Benedictines live so long, all that singing. I love to sing and was blessed to be made cantor, a role I could barely only live up to. Luckily there were expert singers and so I apprenticed myself to them and learn to site read. But I remember getting ready to lead my first Sunday Mass, I spent 17 hours in preparation!

One thing i noticed about daily singing together is that the times when there was dissent in the community, then we could not sing together, could not harmonize with one another. It turns out that you cannot sing with someone you are angry with. You won’t allow yourself to do it, you will stay a half a step above or below him but you will not allow yourselves to sing in precisely the same pitch. But then it sounds terrible as these days, which were not often, did occur and often involved many of the brothers all at once.

So you are singing in public, but as the office proceeds you find yourself forgiving your brother and expressing your forgiveness by your willingness to harmonize with him. He reciprocates a little by allowing himself to harmonise with you and then you allow yourself to forgive him a little more and by the end of the office you are singing in harmony and the trouble in the community is gone. I experienced many times and each time I found it to be a miracle. It really wasn’t a miracle, It is just the power of human hearts bound by vows of faith before God.

The monastic experience was life-changing for me, a crash course in community living. It was my introduction to renunciate life, self-definition that helped to articulate the movement away from the ordinary societal script and social expectations. It was a great lesson in recovering what I knew to be in my soul but what had been lost from the broader collective understanding, the longing to penetrate the mystery of life and know ‘why we are on this earth.’

If monasticism is no longer a salient feature in the modern Western psyche, it only speaks to the crisis of the modern Western psyche, for such a call transcends time and culture. While I knew this instinctively upon entering, I did not have the language for it. But thanks to my mentors and the many great souls in that community, I was initiated into a ancient world of living ideas and ideals.

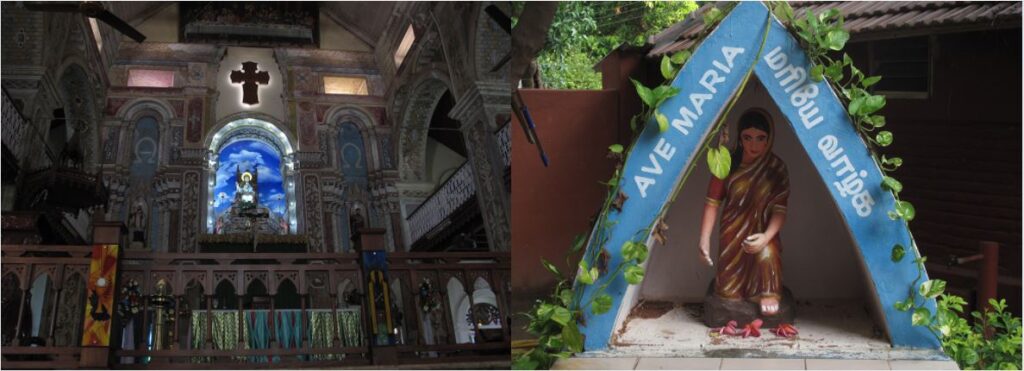

I had discovered India in my travel years and knew it to be a holy land, knew how focused its people were to the life of the spirit. Still today in India, temple life and worship remain at the centre of the culture. In such a world, God is the axis mundi and all other human endeavours — social, political, economic — are subordinated to that. Of course this is all changing very rapidly now and soon India will be in the same position as the West.

– I remember you told that you came to India due to the illness. Is it right?

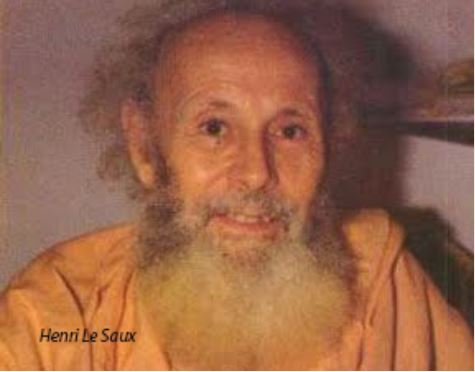

– Yes, that is exactly right. While living at the monastery in California, I had read the diaries of Henri Le Saux, the French Benedictine monk who came to India in 1948 and lived out his life here until his death in 1973. One of the places he waxed poetically about was Ramanasramam and Arunachala mountain. When I read the hymns he composed about this place together with his compelling life story and deep penetrating theological insights in respect of the link between Christianity and Advaita Vedanta, I made up my mind that if I got the chance to return to India, I would go on pilgrimage and would Tiruvannamalai my first stop.

As it would happen, I suffered a back injury in an intensive meditation retreat and was on crutches for six months. Since I continued working the doctors became concerned that I was not taking the needed rest for such an injury and recommended to my superiors that I take a four month leave. Even after just a few weeks on leave, I was able to get off the crutches and instead of rushing back to the monastery, followed the unofficial advice of Benedictines that when you get a leave, make use of it and don’t return early. So I made up my mind to use the full four months and booked a ticket to India for a two-month ten-stop pilgrimage.

It so happened that the night I arrived in Tiruvannamalai was a full moon and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims were here going in devotional circumambulation around the Holy Hill and thus my taxi could not reach Ramanasramam due to the crowd. As I hadn’t really walked much in six months, I left my small bag in the town and began walking in the rain with the countless thousands.

After two kilometres I reached the Ashram where Henri Le Saux had had his advaitic experience in the presence of Sri Ramana Maharshi, the great south Indian sage. Arriving there around 10 pm, the rain was pouring down in such profusion that there were actually small waterfalls coming down through the Ashram and rivulets of flood water on all sides. I was exhausted both from the two-day journey from North America plus the strain of walking two kilometres after six months having not been able to walk at all. So I took a position under the veranda of the Ashram office which was by this time closed for the day, along with hundreds of others seeking shelter from the inclement weather.

I lay there peacefully and there were bodies on every side of me. With five or six people pressed up against me, it felt as though I were in the in the womb of the mother, amongst these peaceful sleeping people taking refuge from the cool wet night. Immediately I fell asleep. When I woke perhaps an hour later, I knew this was a special place and intuited that I was going to be staying here longer than planned and would never see the other pilgrimage destinations. By the second evening, I knew that I was not going to want to leave from here at all.

All of a sudden I found myself in a discernment crisis: I was due back in the monastery in two months but how could I ever hope to build a life of such devotion and faith in the West, even in my monastery?

The two months passed by quickly and I got an extension and willingly gave up my airplane ticket without being able to get any refund. I struggled with the ongoing discernment, so deeply that for those two months I did not sleep much.

– Then you missed the second flight… Can you tell now the story about the taxi driver who taught you what is true faith?

– I had to go to the immigration office and register my papers. It was a somewhat important errand so when I got into the auto-rickshaw, I was a little annoyed that the driver was taking his time getting ready to go. He was cleaning his altar which was the dashboard of the three-wheeler and preparing a worship service. As he carried on, I was becoming nervous about making the appointment.

Finally, about the time that the flame was lit and he was performing worship to the deity in his vehicle, I laughed to myself thinking that I, a monk, who imagined myself as a man of faith, was taught by a taxi driver as how to live the life of faith day to day. I felt both ashamed at my earlier annoyance, and grateful to be in a country where taxi drivers could remind you what the life of faith consists in, namely, slowing down and honouring each moment held and blessed by the divine.

About Michael Highburger

- Born in the United States in 1960, Michael Highburger spent six years studying Continental philosophy for his BA at UT Austin, Baylor University and the University of Copenhagen. He did his graduate work in philosophy and linguistic anthropology at UT Austin with a later stint at Brite Divinity School.

- Living one year in Africa followed by one year in Israel, he did his field work in Guatemala. Subsequently he did seven years of non-resident training in Buddhist meditation in the Kapleau lineage at Rochester Zen Centre in upstate New York before taking up residence at New Camaldoli Hermitage, a Camaldoli Benedictine community in Big Sur, California in 1997, where he took first-year vows as a junior monk in October 1998.

- In October 2000, he moved to Sri Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, South India, the community where he now serves and edits a monthly English language e-magazine and assists in hosting (Christian) groups from the West. Michael Highburger Lives very close to, and often cooperates with, the inter religious dialogue centre Quo Vadis, which Danmission supports.

- Having authored and edited various books on the Advaita Vedanta of Ramana Maharshi, his 17 years in India has been devoted to the study of interfaith dialogue with Hinduism and Buddhism including participation in various interfaith dialogue conferences.