I had never read anything about Ramana Maharshi, I had not read much of anything at all. I had hardly ever heard the name. I was not a seeker. I was five years old and I came because my parents decided it was what they wanted to do and at five one doesn’t have a voice when it comes to decisions like where to live.

Memory is a curious attribute. Many things are bright and clear throughout the river of life, while others blur and fade or else change emphasis as well as shape and form and seem to evolve into something different. My memories of arriving in India are fractured and mainly unclear, but my memories of arriving in Tiruvannamalai are surprisingly coherent. It was hot, that I can clearly state, and it was also incredibly dusty. Why the dust should have made such an impression on me I now find hard to understand but in my mind’s eye there is a soft pall of pale gold dust over everything. It was in the air and on the road. After dark the dust was cool and welcoming to the feet like puffs of talcum powder. Although the place was new and strange, I never associate a feeling of strangeness with Tiruvannamalai. Perhaps because it was such a short time before it became familiar as home. In the way of children my brother and sister and I rapidly learnt the language and made friends with other children. It cannot have been quite as quick as my memory recalls because my brother Adam was barely walking when we arrived and my sister Frania was a babe in arms. Our friends were the gardener’s daughter and the children of the Ashram: Sundaram, who is now the president, Ganesh and Mani, as well as their sisters. But all that happened later.

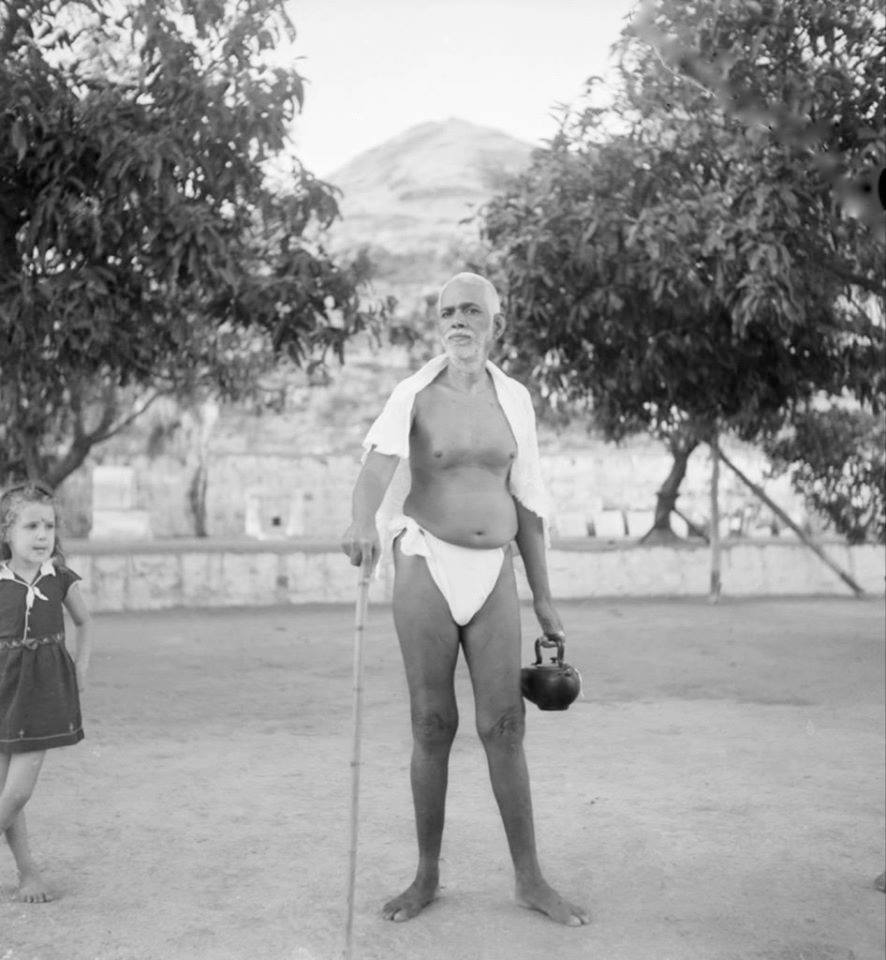

The first time I saw Bhagavan is as clear today as it was at the time, all those many years ago. It must have been the day after we arrived. My father was not with us as he had been interned in a concentration camp in Bangkok where we had lived previously. With us three small children clustered around her, my mother went to the Ashram for the first time to receive Bhagavan’s darshan. As the oldest I was in charge of the tray of fruit we were bringing. It had been explained to us that the only acceptable gift to Bhagavan was fruit, which could be shared in the dining hall later. The tray I bore, laden with bananas and oranges, felt huge. My arms were stretched around it and it threatened to wobble free and spill everything onto the ground. It took intense concentration to keep things from collapsing, but it was my responsibility and I took it seriously. We walked across the open space that was occupied by a few sleeping dogs, some squirrels and a peacock. (The space is now a beautiful hall with a polished granite floor and a shrine at one end where Bhagavan is buried, but was then just bare ground inhabited by various animals waiting their turn to seek Bhagavan’s darshan.) Then we entered the cool hall where he sat, known now as the Old Hall but in those days it was the only hall and the main entrance was a door opposite the couch. It is now a window.

We entered and saw Bhagavan straight away, sitting on the couch in front of us. There he was.

Seeing him, all the rest of the room and the people faded away. There was such a presence, and yet it didn’t feel strange. He seemed luminous and magical and friendly all at once. I stood there staring at him, not knowing what to do with my burden of fruit. He smiled and pointed to a stool at the side of the couch that was used to receive such offerings. I didn’t know that and since there was no guard-rail around him back in those days, I sat myself down on the stool with my back to Bhagavan and smiled happily at all the people in the hall who were smiling back at me. We were the first European children to come there and a definite novelty. I was still holding the tray. Bhagavan laughed and made a remark in Tamil, which we didn’t yet understand. It was translated to me. He had said that I was making an offering of myself. All the rest of my life when I have got myself into one sort of mess or another, that remark has given me the courage to go on.

After all, Bhagavan must surely help one who has made an offering of herself.

The years of our childhood were spent running in and out of the hall. Frania learnt to walk there, Adam learnt to run and I learnt whatever it is one learns when playing at Bhagavan’s feet, most of it probably by osmosis. It was there that we saw the animals come to visit him. The peacock would come through the door and right up to the couch, then the beautiful tail was spread and it would dance. Bhagavan watched-we all watched-as though it was a formal programme, and when it was over Bhagavan gravely acknowledged the peacock’s performance and it left. The squirrels came to the door and glanced around nervously, then there was a dash to the couch and up onto Bhagavan’s hand or knee. He sometimes gave them puffed rice from a small tin kept for the purpose. Dogs came and prostrated themselves before the couch and monkeys chattered to him from outside the window. They were frequently chased away but as frequently reappeared. One time someone showed Bhagavan a paragraph in the newspaper where there was an announcement that vans were touring the villages and collecting monkeys for sale abroad for experiments. Bhagavan laughingly said to the king monkey who was clinging onto the bars of the window beside his couch:

“Did you hear that? It isn’t safe for monkeys here right now so you better take your tribe away.”

When the vans came there wasn’t a monkey in sight. Not one in the whole ashram area. Later I heard someone comment that no monkeys had been caught in the whole of Tiruvannamalai.

Then of course there was Lakshmi the cow. She would wait for Bhagavan outside the back door or call for him to come out and then she would snuggle up to him and rub her head against him, or else he would go and visit her in the cowshed and sit down beside her. They spoke together and it was obvious that she adored him. It was also obvious that she was a very special lady. I think that all the animals considered that he was one of them, albeit in a special way, and come to think of it the humans seemed to think more or less the same thing.

The amazing thing is not that all the animals came to Bhagavan, it is that we all accepted it and took it for granted without being amazed. Of course children believe in magic as a part of everyday life, but even the grown-ups accepted it as completely natural as far as I remember. Adam, Frania and I came to Bhagavan with our toys to show him, with our books and puzzles to share with him and with our secrets to confide in him. He treated us children with the same courtesy and gave us the same attention that he accorded to the adults with their problems. He also laughed with us. With the passage of time, and the realisation that he was the great Sat-Guru, people forget in their reverence that Bhagavan had a great sense of humour and the hall often rang with his laughter.

Our lives revolved around Bhagavan and the Old Hall. We all played on the rocks of Arunachala and made ships or castles out of their shapes, but we gravitated back and until we were severally sent off to school, the hall was the focus of our lives.

Bhagavan sat in one corner with a small revolving bookcase beside him. He kept his favourite works there for easy reference and he often shared something from one of the shelves with someone who asked him for clarification, that is, if he didn’t give his usual reply along the lines of: “First find out who is asking the question”. He did however occasionally get involved in points of doctrine. I was in the hall when he was explaining about the spiritual heart on the right side of the body. This surprised me as I had naturally assumed, as children do, that the heart was on the right side of the body and couldn’t comfortably imagine it anywhere else. Why would that be spoken of as something remarkable? I was in the hall when people sometimes came crying with inner pain. A look from him was often all it took to heal them. It was in the hall that I brought my new paper-folding book. I had received it for my birthday and one of the designs just would not work out. I tried it again in front of Bhagavan and of course this time it worked. I knew it would. People would show him their letters, sometimes from loved ones and sometimes with news such as job opportunities. We showed him everything, every part of our everyday lives.

I wrote to my mother from school and asked at the end of the letter to be remembered to Bhagavan. She showed him the letter and he said:

“If Kitty will remember Bhagavan, then Bhagavan will remember Kitty.”

Another remark that has given me comfort over the years.

We all, humans and animals came to Bhagavan to show him our triumphs and our troubles and we knew he would deal with it all and understand it all, often, in fact usually, without a word being spoken.

The long part of the hall at Bhagavan’s feet was where people sat as a rule, the men on the left and the women on the right with a natural passageway in between. Some in silent meditation, some with something to say or to ask and waiting for the moment that seemed appropriate, and some just sitting there, luxuriating in Bhagavan’s presence. Twice a day, morning and evening, the pujaris came and sat up near his couch and chanted the Vedas. First it was a few older men, and then after Chadwick inaugurated the Veda school, there was a leavening of young boys.

Although Bhagavan could be friendly and approachable, there were times, and usually one of them was when the Vedas were being chanted, when he would close his eyes and go away. To see him then was awe-inspiring. He looked exalted. At times like that one could hear a pin drop. No one even wanted to breathe too loud. It is strange to reflect on how many moods and faces Bhagavan could wear and belong to none of them. We children accepted it all without question. Bhagavan was Bhagavan and of course he could do anything and be anyone he chose-well naturally.

With peculiar elasticity, our time in Tiruvannamalai seemed to both pass in a flash and also to encompass our whole lives. It was barely a year from when I entered the hall for the first time till I was packed off to school, a development that seriously interfered with my education which was advancing very well indeed in the Ashram and on the Hill. My mother didn’t agree with my arguments, so school it was. Every holiday back I came and Bhagavan was there, just the same as ever, and so we slipped seamlessly into our old lives. The Hill and the hall never changed and, as far as a child’s eyes could judge, neither did Bhagavan. We didn’t notice that his body was getting older. I wish now that I had spent more time sitting in the hall instead of climbing a tree with my book. Of course I thought that Bhagavan would be there for ever. Of course he is. from THE MOUNTAIN PATH , January-March 2003

Read about Kitty’s family life in the ashram in this October 1970 edition of The Mountain Path;